Best books of 2017

Part four

Sat 26 Nov 2017

William Dalrymple

India Conquered; The Tartan Turban; The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu

I learned a great deal from Jon Wilson’s India Conquered (Simon and Schuster), an admirably concise, balanced and thoughtful look at how British colonialism maimed India, and the sheer wickedness of so much of what we did there. The product of many years of detailed archival research, Wilson’s book is without question the best one-volume history of the Raj currently in print. I also hugely enjoyed John Keay’s The Tartan Turban (Kashi House), about the allegedly half-Aztec, half-Scottish mercenary Alexander Gardner. Minutely researched, wittily written and beautifully produced, it brings back from the dead one of the most extraordinary figures in the history of travel and exploration and stands as one of Keay’s most memorable achievements. Charlie English’s The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu (HarperCollins) tells the story of how the priceless literary remains of this ancient city’s golden age were smuggled to safety after al-Qaida jihadis took over and imposed sharia law in April 2012. It reads like a sort of Schindler’s List for medieval African manuscripts and is an exemplary work of investigative journalism that is also a wonderfully colourful book of history and travel.

Martha Kearney

Home Fire; House of Names; Autumn

Why do some people become radicalised? It’s a question I’ve explored with experts on air, but perhaps fiction can provide greater insight. Kamila Shamsie’s powerful novel Home Fire (Bloomsbury Circus), inspired by Sophocles’s Antigone, did just that. Colm Tóibín also draws on Greek tragedy for his masterly House of Names (Viking). The escalation of violence and desire for revenge has deliberate echoes of the Irish Troubles. Autumn (Penguin) by Ali Smith, the story of an unlikely friendship, displays surreal imagination with her characteristic linguistic playfulness.

Ayobami Adebayo

What it Means When a Man Falls from the Sky; The Zoo; When I Hit You

I’d been anticipating Lesley Nneka Arimah’s debut since I read one of her stories years ago, and with its remarkable range and exquisite prose, What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky (Tinder Press) did not disappoint. In The Zoo (Faber), Christopher Wilson reimagines Stalin’s final days in power through the eyes of Yuri, a brain-damaged boy who becomes the dictator’s food taster. The result is a witty, tender, entertaining and sinister satire. Meena Kandasamy’s vivid, sharp and precise writing makes a triumph of When I Hit You: Or, a Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife (Atlantic), her searing and unflinching portrait of an abusive marriage.

David Kynaston

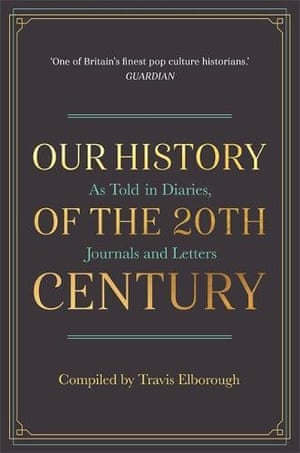

Joining the Dots; Our History of the 20th Century

Joining the Dots (HarperCollins) by the social historian Juliet Gardiner is such an accomplished and intensely evocative memoir that it will become in time an integral part of our understanding of postwar Britain. It is also, at a personal level, a journey of courage and determination. Travis Elborough’s resourceful, finely judged compilation, Our History of the 20th Century (Michael O’Mara Books), complements it well, drawing on an eclectic range of diaries and letters to open up the story of modern Britain.

Tom Holland

Viking Britain; Manhattan Beach; The Art of Failing

Fresh, vivid and impeccably researched, Thomas Williams’s Viking Britain (HarperCollins) was the most rip-roaring work of nonfiction I read this year. The novel I most enjoyed was Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach (Corsair), a historical thriller that was quite as visionary and stylish as one would expect from the author. The funniest book was Anthony McGowan’s The Art of Failing (Oneworld), which alternates self-mocking slapstick with flashes of weirdness reminiscent of Gogol.

Tahmima Anam

Home Fire

The standout book of the year for me is Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire (Bloomsbury Circus). It’s a modern retelling of Antigone set among a family divided by politics, love, and radicalism. In less than 300 pages, it managed to do all the things I want novels to do – tell me something about the world, give me a tiny glimpse into the otherness of others, and, most of all, give me that ache of longing as I turned the last page and realised I would never meet these characters again.

Rohan Silva

Fresh Complaint; A Place for All People

I adored Fresh Complaint (4th Estate), the new collection of short stories by Pulitzer prize-winning novelist Jeffrey Eugenides – it’s beautifully written and couldn’t be more topical, with tales of rape allegations on campus and transgender teens. Architect Richard Rogers’s memoir A Place for All People (Canongate) was my other favourite book of the year, showing how our cities could be fairer, greener and more beautiful.

Mariella Frostrup

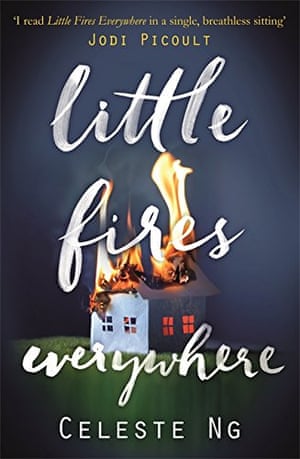

American War; Little Fires Everywhere; Exit West

America’s tortured present lends unsettling believability to American War (Picador), the dystopian debut from journalist Omar El Akkad with its late 21st-century picture of a second civil war, fought over fossil fuel in a US devastated by environmental disaster. Brilliantly imagined, it’s both a timely tale and a salutary warning. Little Fires Everywhere (Little, Brown) is the second novel from Celeste Ng and manages to combine a thought-provoking story of race, belonging, motherhood and the cracked face of smug liberalism with the pace of a page-turner. Mohsin Hamid always makes you think and his Booker-nominated novel Exit West (Hamish Hamilton) is a beautiful, poignant story of love, longing and the agony of being uprooted and displaced among the migrating millions.

Linda Grant

Love & Fame; Reservoir 13; The Dark Flood Rises

Susie Boyt’s new novel Love & Fame (Virago) is characterised by the individuality of her voice. She writes sentences with the nuance of a playful Henry James, exploring grief with wit and wisdom. Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 (4th Estate), which was unlucky not to have been Booker-shortlisted, is a mesmerising account of landscape, daily life and, running through it, a deepening mystery about a missing girl. Breathtaking. Margaret Drabble’s The Dark Flood Rises (Canongate) is an absolute tour de force about old age and dying. Scandalous that it wasn’t a major prize-winner.

Frank Cottrell-Boyce

The Lost Words; Dethroning Mammon; Dislocating the Orient

As so often, the most beautiful and thought-provoking book I’ve read this year was a children’s picture book, The Lost Words (Hamish Hamilton), about the way words help us see more clearly, in which Robert Macfarlane’s charms are brought to life by Jackie Morris’s dazzling images. Justin Welby’s brisk, challenging Dethroning Mammon (Bloomsbury) was originally a Lent book but would work just as well for new year. We should probably read it as a nation because it would sort out our priorities. And then Daniel Foliard’s Dislocating the Orient: British Maps and the Making of the Middle East 1854-1921 (University of Chicago Press); I can’t understand why our kids are taught all about Vietnam but not this.

No comments:

Post a Comment