|

| Edward Goldsmith |

Edward Goldsmith: Environmentalist who founded 'Ecology' magazine and championed the green movement

David McKittrick

Sunday 18 October 2009 23:00 BST

Edward Goldsmith devoted a lifetime to "green" causes and the promotion of ecology, spending decades preaching that industrialisation was endangering mankind and that major change was essential if the planet was to survive.

In one sense his approach was radical in that he tackled head-on many of the barely questioned tenets of western society. In another it was conservative in that his remedy was a return to old-fashioned, even primitive forms of political and social life.

The presence of both of these elements in his philosophy, together with the vigour he put into his campaigning, antagonised many and made him many enemies in the course of his long career. But he revelled in the combative. As an ecological pioneer he was often dismissed as cranky. Yet he lived long enough to see much which was initially derided as silly enter the political mainstream, both nationally and internationally.

His home page lists some of his diverse concerns, including biotech, climate, farming, forests, global governance, health, trade and globalisation, technology, waste and pollution. He listed, with what appeared suspiciously like pride, various criticisms that had been levelled at him over the years. "For some of my critics I am now a racist, fascist, neo-Nazi, and extreme right-wing ideologue," he wrote. "But in the past I have been referred to as a Bolshevik, a whacko-communist-liberal, an anarchist, a Jacobin, an omnivorous pseudo-ecological tribalist, a madman and a Palaeolithic counter-revolutionary."

As these epithets suggest, he was too much of an individualist to be slotted into any particular pigeon-hole. He did, however, regard himself as one of the founding fathers of what in time became the Green Party.

He could dish it out as well as take it. He regarded James Lovelock, who formulated the Gaia hypothesis that the earth constituted a superorganism, as an important figure. Yet he variously described some of his views as absurd, ridiculous and crazy.

Goldsmith cheerfully admitted that in his early days as an eco-warrior many people thought he too was touched, especially those who visited his home. "I had a compost toilet that cost me all my friends. They were sick from the smell of it," he remembered. "Quite a lot of people thought I was mad." Mad or not, he certainly had staying power in the ecological world, publishing and often editing a key magazine, The Ecologist, from the late 1960s until the late 1990s.

Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Paris in 1928, Edward Réné David Goldsmith was the son of Frank Goldsmith, a well-off landowner and one-time Conservative MP. In his early years Teddy Goldsmith stayed in family hotels around France, before moving to London, where he initially lived in Claridges. Much of it was "one long holiday," he said, though there was a darker side: "Many of my relations died in Hitler's gas chambers," he later related.

A spell at Millfield School was followed by a move to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied politics, philosophy and economics. He completed his course but, he was to recall, "I realised while I was at Oxford that everything I was being taught was nonsense. It became quite clear that these people didn't know what they were talking about. Everything was compartmentalised. It was impossible to see the whole picture, so I determined to find out why this was the case, and what the whole picture might be."

The family money gave him the opportunity to travel widely. Anthropology "grabbed me," he remembered, and he traversed the Third World studying tribal life. This was not in itself unusual but what was different with Goldsmith was his belief that advanced societies had much to learn from people they regarded as primitive, backward and unenlightened.

"I spent a lot of time in Africa, in tribal societies," he explained. "One thing I became convinced of was that these were the only truly 'sustainable' societies I had ever seen. That word is used a lot nowadays, but then it meant nothing. It seemed extremely important to me, and here were people putting it into practice. Yet their very existence was threatened by the remorseless expansion of industrial society."

His experience left him with an indelible belief that commercialisation, industrialisation, and indeed modern finance structures, were all radically and dangerously wrong. He accused the World Bank, for example, of "financing the destruction of the tropical world, the extermination of its wildlife and the impoverishment and starvation of its human inhabitants."

He simultaneously believed that small was beautiful but also that the key lay in the bigger picture. This came out in his criticism of scientists, who, he argued, "cannot understand each other. They are looking at little bits of reality – that is why they cannot perceive the whole. They are victims of their own specialised disciplines."

It quickly became clear that he would be taking a practical as well as a theoretical approach. In the general election of February 1974 he stood in Suffolk as a "People Party" candidate, riding on a borrowed camel with the slogan "No Deserts in Suffolk. Vote Goldsmith." He lost his deposit but none of his campaigning zeal. This was fully deployed when the authorities thought of siting a nuclear power close to his home: he moved his desk to the site entrance and sat there, preventing diggers from starting work. It worked.

In 1969 he established The Ecologist, which would for decades provide a platform for his views. Funded by his brother, the late billionaire financier Sir James Goldsmith, it sent out the green message to a small but growing band of enthusiasts.

An early issue was a huge success when it was published as a book entitled A Blueprint for Survival. This is regarded as the most important of Goldsmith's many works, Jonathon Porritt describing it as "a get-real summons like no other."

Over the decades more and more people began to subscribe, at least in part, to the messages Goldsmith tirelessly emitted via The Ecologist and in speeches, books and other writings. Inevitably, fissures appeared. When he was described as right wing he responded: "If by right wing you mean conservative then I totally accept this criticism. I am a true conservative in the sense that I believe in the family, in the community, in religion and in tradition."

He could by no stretch of the imagination be described as any sort of conventional right-winger, but many green adherents moved away from him as their movement tended towards the left. Goldsmith did not regard this as a tragedy, perhaps because he relished argument so much. Anger and an element of polarisation were in fact part of his personal mission: "Why aren't more people angry?" he asked.

As Jonathan Porritt summed him up: "He could be withering about every political persuasion, and seriously loved getting people worked up as he challenged their complacent orthodoxies."

Asked in later life about his contribution, Goldsmith replied: "I hope I've helped. If in some small way I've helped to slow the runaway juggernaut that we've created, or make people aware of it, that has to be a good thing. I hope I have done that."

Edward Réné David Goldsmith, environmentalist: born 8 November 1928; married 1953 Gillian Pretty (one son, two daughters), 1981 Katherine James (two sons); died 21 August 2009.

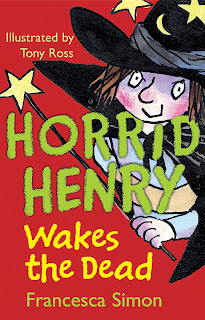

Among the 50-plus books that have followed are the immensely popular Horrid Henry series, which has now sold more than 12m copies in 24 countries. The 17th book in the series, Horrid Henry Wakes the Dead, was published on October 1.

Among the 50-plus books that have followed are the immensely popular Horrid Henry series, which has now sold more than 12m copies in 24 countries. The 17th book in the series, Horrid Henry Wakes the Dead, was published on October 1.