|

| Primo Levi Poster de T.A. |

Friday, January 31, 2020

Arabs, Israel and Terrorism / An Interview with Primo Levi

"Don't Want To Hide," Says Author Salman Rushdie, 30 Years After Fatwa

|

| Salman Rushdie |

"Don't Want To Hide,"

Says Author Salman Rushdie,

Salman Rushdie's life changed forever on February 14, 1989, when Iran's spiritual leader ordered the novelist's execution after branding his novel "The Satanic Verses" blasphemous.

Salman Rushdie's 'Midnight's Children' to be adapted in a series on Netflix

Salman Rushdie's 'Midnight's Children' to be adapted in a series on Netflix

June 29, 2018

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

The Greatest Literature of All Times / Dashiell Hammett

|

| Dashiell Hammett |

The Greatest Literature of All Times

Dashiell Hammett

First of the unholy trinity

The Greatest Literature of All Times / Dashiell Hammett / Bibliography

The Greatest Literature of All Times

Dashiell Hammett

The 100 best novels / No 54 / The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett (1929)

First appearance of works in book form

Tuesday, January 28, 2020

The Distorted, Absorbing New Portraits of Mathieu Laca

Attract and repel: Mathieu Laca’s portraits channel Francis Bacon’s “intensity”

|

| Margaret Atwood Mathieu Laca |

Attract and repel: Mathieu Laca’s portraits channel Francis Bacon’s “intensity”

|

| Arthur Schopenhauer |

Astor Piazzolla / Romance of the Devil

Monday, January 27, 2020

Rereading / In the Skin of a Lion by Michael Ondaatje

Anne Enright first read Michael Ondaatje's In the Skin of a Lion as a creative writing student. Beautiful and highly contagious, it seems to do impossible things - a dangerous influence on an aspiring novelist

Anne Enrigh

Sat 15 Sep 2007

Jane Auster / Persuasion / Review by Emma Tennant

Seeing the light at last

At school Emma Tennant was bored by Jane Austen, but returning to Persuasion changed her mindEmma Tennant

Saturdady 23 November 2002

Sunday, January 26, 2020

Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House / How to Write the Book No One Wants You to Write

How to Write the Book No One Wants You to Write

SEPTEMBER 25, 2019

O.J. Simpson case helped bring spousal abuse out of shadows

O.J. Simpson case helped bring spousal abuse out of shadows

By MARYCLAIRE DALE

June 12, 2019

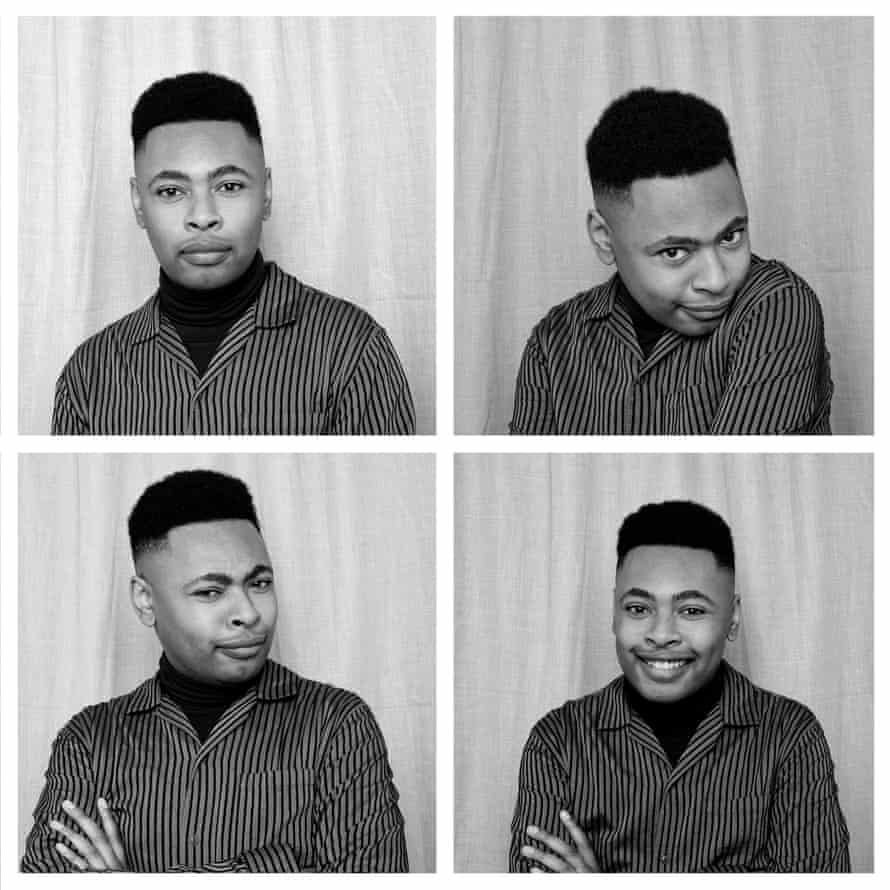

Introducing our 10 best debut novelists of 2020

|

| From left: Jessica Moor, Paul Mendez (top) Elaine Feeney, Abi Dare (top), Beth Morrey, Stephanie Scott, Naoise Dolan (top), Douglas Stuart, Deepa Anappara, Louise Hare. |

Introducing our 10 best debut novelists of 2020

All first-time authors dream of becoming bestsellers. The Observer’s past picks have included Sally Rooney and Jessie Burton – who among this year’s crop will make it big?

by The Observer26 January 2020

S

For the seventh year running the Observer New Review has chosen a select group of first-time British and Irish novelists we believe will make their mark. Our selection procedure was rigorous, with all eligible novels being scrutinised for readability and literary merit by a handful of editors on the New Review. And the class of 2020 looks particularly promising. Among those who made the grade were a poet, a journalist, a former teacher and an actor. The subjects they take on range from modern love in Hong Kong, child kidnapping in India and the Japanese marriage breakup industry to the brutality of Thatcher’s Britain and murder in a women’s refuge.

What makes us so sure these new writers will stand out from the crowd? Our track record speaks for itself. Former New Review debut novelists include both Rooney and Burton, Gail Honeyman, Emma Healey, Oynikan Braithwaite and Sara Collins, winner of this year’s Costa debut novel award. Two of our chosen writers are Irish, demonstrating that the exciting new wave of Irish writing kicked off by authors such as Rooney and Booker prizewinner Anna Burns is no flash in the pan. And having called in recent years for publishers to address the scarcity of new black and minority ethnic writers, we are delighted to present our most diverse group of first-time authors yet, with four BAME writers out of the 10. Only two are men. Does this mean the days of the Great White Male Author are numbered? We shall see.

‘When I told my family I had a novel coming out, one uncle asked if I’d had a ghost writer’Paul Mendez

Author of Rainbow Milk (Dialogue, 30 April)

They say write what you know – and 37-year-old Paul Mendez had plenty of material to draw on for his first novel, Rainbow Milk. Like his protagonist, Jesse, Mendez was raised in the Black Country as a Jehovah’s Witness, and “disfellowshipped” by the group at 17. Like Jesse, Mendez moved to London and became a male escort and sex worker, part of a journey of self-discovery that forms the core of his beautifully assured book.

He spent several years transforming his experiences into fiction: “There were times when to write something directly autobiographical would have simply been to bleed my heart out on to the page,” he says. “There are things that happened to me in it, but the details are far different.”

Rainbow Milk will be published by Dialogue Books, a Hachette imprint founded in 2017 to publish under-represented voices, headed up by Sharmaine Lovegrove. Mendez had met her at a party in 2012, but it wasn’t until he read about Dialogue that he followed up: “I sent her a sprawling 300-page manuscript on her first day,” he laughs.

Mendez lives in Hampstead and is studying for an MA in black British writing at Goldsmiths.

What made you want to be a writer?

I was raised studying the Bible with adults – and it’s the greatest book ever, right? So my literacy accelerated at a very young age. Books have just always been the thing; I’ve never been able to escape words.

When did you start writing?

I was always encouraged by my English teacher to write, but Witnesses don’t encourage any kind of creative application, so it was a real conflict. I quit an engineering degree in 2002 to write. My family isn’t at all literary and when I told them I had a novel coming out, one uncle asked if I’d had a ghost writer. They’re wonderful people – just very different. They’re still Jehovah’s Witnesses, and they think I’m stupid: I was taught the “truth” and decided to go against that. I’ve tried to give up on them, but I really can’t. They may give up on me after this book comes out – who knows?”

What do you think about the world of books and publishing in 2020?

I think it’s our great hope! Dialogue Books, Merky Books, Jacaranda Books – all of these imprints are now around, looking for people with different and very valid voices. We’re in a good place.

What do you need to work?

I need boringness – for nothing to be happening.

Have you been mentored or particularly encouraged by anyone?

It was a fantastic leap of faith on Sharmaine’s part to say “I believe in you, you can write – go away and do it.” I needed someone to do that.

What books have inspired you to be a writer?

James Baldwin – say no more! And Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty: it was one of the things that made me realise I could write through the voice of a gay black protagonist.

What books are currently on your bedside table?

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, Gender Trouble by Judith Butler, and Flèche by Mary Jean Chan.

What single piece of advice would you offer to aspiring writers?

Keep. Going.

What’s the best and worst thing about being a writer?

There’s two amazing things: being part of a community of brilliant people, and always having the ability to put your thoughts into words. Therapy is great – but it’s also great to be able to open your laptop and talk to yourself. The worst thing? So far, nothing!

Interview by Holly Williams

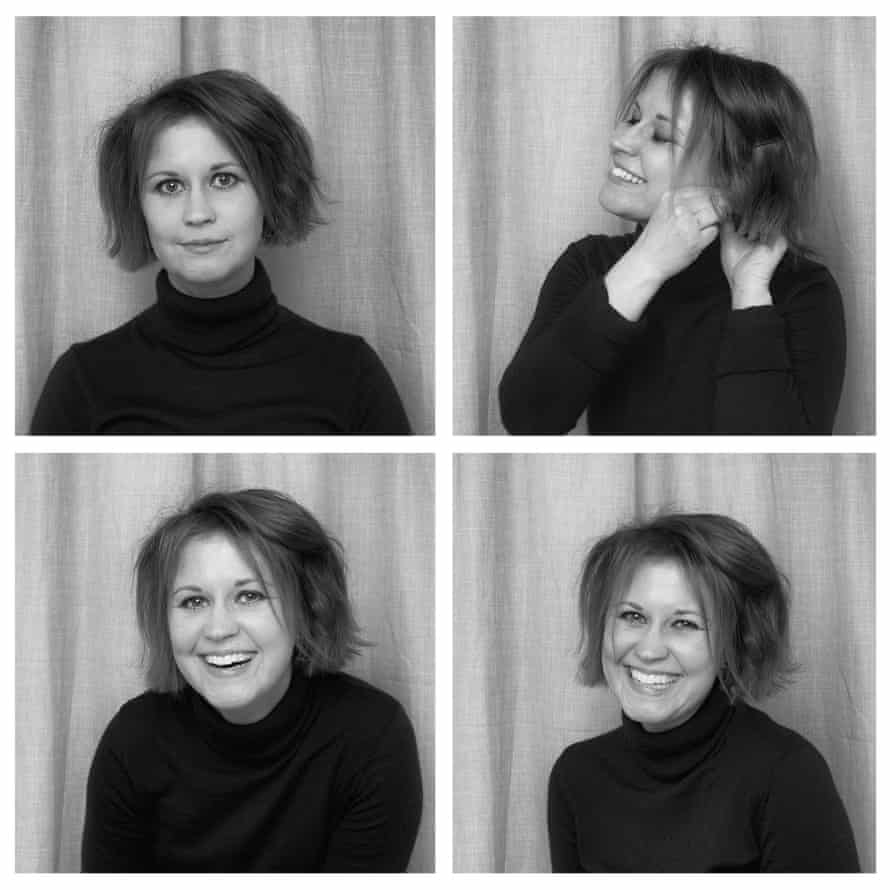

‘My book was born out of trying to provide answers’

Abi Daré

Author of The Girl With The Louding Voice (Sceptre, 5 March)

Abi Daré, 38, was born in Lagos, Nigeria, where she planned to study French at the local university. Her mum had other ideas and at the end of one summer holiday in the UK Daré found herself “tricked” into staying on to study law at the London campus of the University of Wolverhampton. These days, she’s a proper enough Londoner to have moved out to Essex, but wWhen she first arrived, she chronicled her immigrant experience in a blog that drew hundreds of thousands of hits. In fact, it became so successful she had to delete it because she felt her privacy was being invaded. Aside from the importance of not using your real name online, the blog taught her that she could truly write, so she replaced it with fictional stories shared among friends and family. The Girl With the Louding Voice began as the thesis for her creative writing MA at Birkbeck, University of London, and wound up winning the Bath novel award for emerging authors, before being tussled over in a five-way publisher auction. Its heroine is 14-year-old Adunni, a village girl who longs for an education. Instead, she’s sold into a brutal marriage from which she escapes, only to become trapped as a domestic servant in Lagos, where she’s haunted by her predecessor’s disappearance. To save herself, she must find her “louding” voice. The novel has already been chosen for BBC Radio 2’s Book Club, and Daré hopes it will shine a light on the plight of the real-life Adunnis who continue to be exploited.

How did you come to write this book?

As a child, I noticed that a lot of families – including mine – had informal housemaids, many of them uneducated and ill-treated, and as young as eight or 10. When my own daughters got to be that age, I found myself wondering whether it was still happening. I read an article about a 13-year-old who had been scalded with boiling water by the woman who employed her, and what really got to me was that her face was a blur in the photograph. It was to protect her identity, but I thought, who is this girl? What’s her story? My book was born out of trying to provide answers.

What do you think about the world of books and publishing in 2020 – rude health or room for improvement?

It’s come a long way. I’ve gone from not seeing books by authors like myself on the shelves to seeing a lot more but publishing is still not representative enough.

Where do you write and what is your work schedule?

I have a full-time job overseeing app development, so I do a lot on the go. In fact, I’m talking to you from a watch I bought so that I can text myself when I get ideas. I wrote most of The Girl With the Louding Voice in a coffee shop where there was a poster of a girl that the chain’s foundation was supporting. She had the brightest smile, and it felt like she was saying: “Keep going, do it for me!”

What do you need to work?

I like background noise when I’m writing and being creative, but I like silence to edit so I go to the London Library, where I was given a wonderful scholarship. I also get quite inspired in the shower.

What books have inspired you to be a writer?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s books showed me that if she could do it, I could.

What books are currently on your bedside table?

A Woman Is No Man by Etaf Rum and Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens are both on my Kindle.

Are you working on your second book and if so what is it about?

I am but it’s at the point where what it’s about changes every day. I never used to be a plotter but I had a disastrous manuscript a few years ago that was 100,000 words of nothing, so I at least need to have an end scene in my mind now.

Best and worst things about being a writer?

The worst thing is when you’re just not able to get the words out. The best? One is obviously writing a story that I enjoy, another is getting good feedback. When people say “I loved this”, or “Your book opened my eyes”, that beats any feeling.

Interview by Hephzibah Anderson

‘I come from a background where you’re expected to work for a living, making up stuff is seen as a luxury’

Deepa Anappara

Author of Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line (Chatto & Windus, 30 January)

Deepa Anappara grew up in Kerala, India, and worked as a journalist for 12 years, in Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi, reporting on the impact of poverty and religious violence on the education of children. She moved to the UK in 2008 and embarked on an MA in creative writing at the University of East Anglia, where she began work on her debut novel, Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line. Submitting extracts of the novel to various prizes for unpublished fiction in the hope that a longlisting might help secure her an agent, Anappara went on to win a host of awards including the Lucy Cavendish fiction prize in 2018, which recognises literary merit and “unpoutdownability” and whose previous recipients include Gail Honeyman and Sara Collins. The novel became the subject of a nine-way bidding war and has since sold to 20 international territories and received advance praise from literary figures including Anne Enright and Ian McEwan, a historical novel, as part of her PhD in creative and critical Writing at UEA.

What made you want to be a writer?

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to write. But I come from a background where you’re expected to work for a living so if you sit around making up stuff it’s seen as a luxury and indulgence that you can’t really afford. So I chose journalism because it allowed me to write and also point to the inequities in the society in which I was born and raised.

How did you come to write this book?

As a reporter in India, I came across stories about the disappearance of children. More than 20 children had gone missing over two or three years and no action had been taken to find them because these people had no money or political power, and they were being ignored by government institutions. My interest was always in the children’s stories: I wondered what it would be like to be a child seeing your friends disappear and be aware you’re in danger yourself.

If you had to sell the book in a sentence what would you say?

It’s a coming-of-age story about a nine-year-old boy who fancies himself to be a detective and tries to uncover why children are disappearing from his neighbourhood, exploring the impact of a horrific tragedy on a community neglected by the outside world, and the bonds that help people survive difficult times.

What do you think about the world of books and publishing in 2020?

I’d like to see books by more writers of colour and those books get more publicity. I’d like there to be more emphasis on different ways of storytelling. There’s a difference in how stories are told in different countries and we don’t see that variety.

What books have inspired you to be a writer?

The first writers I read were in my mother tongue Malayalam. Kamala Das and Sarah Joseph showed me that women writers could, and must, write about subjects that were considered taboo in the conservative society in which I grew up. I read VS Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas at a time when my parents were struggling to put together the money for their own house, and it was the first time I had seen people like us being represented in fiction in English.

What single piece of advice would you offer aspiring writers?

I heard Anne Enright say that the students of hers who got published were those who didn’t give up and that’s really stuck with me. You have to keep working, keep trying, keep persisting.

Interview by Hannah Beckerman

‘I think I give my friend a headache when I talk about all of my characters’

Elaine Feeney

Author of As You Were (Vintage, 16 April)

Irish poet Elaine Feeney’s first novel, As You Were, is set over the course of one week in a chaotic hospital ward – a context rich in both tragedy and comedy. Feeney, who lives in Athenry in west Ireland, has some experience of hospitals, having spent some time in one after complications following the birth of her second son. “The novel went into a completely fictional space, but what I was thinking about was the camaraderie between people who would ordinarily never be together,” she says. Plus, “no one had private rooms, so you hear everything”. Feeney has already published three collections of poetry and has written as many discarded novels. “There was an anxiety around writing a novel that I didn’t feel around writing poetry, weirdly,” she says. “Also I had my first son quite young – I was only 22 – and poetry was quicker.”

What made you want to be a writer?

Reading. I was a very isolated, introverted kid, and I loved books. I started off with Hans Christian Andersen, the Grimm Brothers, Black Beauty….

How did you come to write this book?

I started to write As You Were around the end of 2014, it took four years and it was a hard write. But I had this voice of the narrator, Sinead, and I just kept knocking.

What do you think about the world of books and publishing in 2020?

People are reading books again – we worried it was all screens, but people have gone back to books.

Where do you write and what is your work schedule?

I teach boys at a Catholic secondary school, and creative writing at the university in Galway, and I have two sons. So I am busy! I plonked my desk in the big open-plan kitchen in our bungalow and I just put headphones on and do the work. It’s the house I grew up in, so it’s got a very weird energy. When my parents were selling I said I’d buy it; I like being rooted.

What books have inspired you?

Edna O’Brien. Maeve Binchy. The poetry we did in school was extremely important: I found my teens quite hard, and I remember reading Patrick Kavanagh’s Inniskeen Road which is about isolation – and I discovered: “Oh, this isn’t a unique feeling, you can get through this.”

What books are currently on your bedside table?

I’m reading a very strange book that came out in the 90s called I Could Read the Sky by Timothy O’Grady. It’s the tightest prose.

What is the best debut novel you’ve read?

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett. It’s stunning. She’s also my friend! But we write completely differently: I think I give her a headache when I talk about all of my characters.

Are you working on your second book?

I’m interested in the workings of institutions and power in everyday life. My next one is going to be set in a rightwing Catholic school.

What single piece of advice would you offer to aspiring writers?

Pay it forward if you get a break – don’t be an ass, be nice.

HW

‘I wanted to write a book about hope that would make people cry in a happy way’

Beth Morrey

Author of Saving Missy (HarperCollins, 6 February)

Beth Morrey, 42, grew up in Derbyshire before studying English at Cambridge, and left university with ambitions to become a comedy writer. A career in factual television beckoned instead and she eventually joined the production company RDF Television, rising to become creative director, responsible for shows including The Secret Life of Four-Year-Olds and 100-Year-Old Drivers. It was while on maternity leave that she decided to embrace her long-held ambition to write a novel and the result, Saving Missy, became the subject of a 10-publisher auction and has since sold in 16 overseas territories. It’s a book about community, loneliness and unexpected friendships, continuing the trend for “up lit”.

What made you want to be a writer?

I wanted to see my name on the spine of a book in a bookshop. I’ve always written since I was about five, when I wrote a story about Icarus. I wrote in television but I wanted to be a writer of books.

What was the inspiration for Saving Missy?

It was Joss Ackland in First and Last, which was a drama years ago about an old man who walks from Land’s End to John O’Groats, and who falls en route while his wife is secretly watching him. I found that scene so poignant, and I wanted to capture something about the poignancy and stoicism of old age. The idea grew from there. Then I was pushing a pram around the park and it struck me how many different people I knew there, from all walks of life, and how we’d been brought together by the dogs [we were walking]. So when I was thinking about this protagonist who was lonely and old I thought that if I gave her a dog, that might be the one simple thing that changes her life.

If you had to sell the book in a sentence, what would you say?

I wanted to write a book about hope that would make people cry in a happy way.

Where do you write and what is your work schedule?

It’s very strict. I go for a run and then I write from 10am-2pm in a cafe that I love. I like background noise and chatter because I find I can tune in and out of it. And then I come home, have lunch and edit until about 5pm, when I go and pick up my kids.

What books have inspired you to be a writer?

About a Boy by Nick Hornby was a huge influence on me. I really like that sparse, puritan prose where it seems straightforward but it’s not. And Sue Townsend – I grew up with the Adrian Mole books, adored them, read them over and over again.

What are the best and worst things about being a writer?

The best thing is when stuff comes out of your head that surprises you: that’s wonderful. The worst thing is the scrutiny. I know that not everyone is going to like my book and I’ve just got to take it on the chin.

What single piece of advice would you offer to aspiring writers?

Lots of people say: “I’ve got a book in me.” But they never actually get around to it. It’s hard to get to the end of a book, to write those 90,000 words. And so I’d say, if you write to that extent then you are a writer, and what happens after that is just luck.

HB

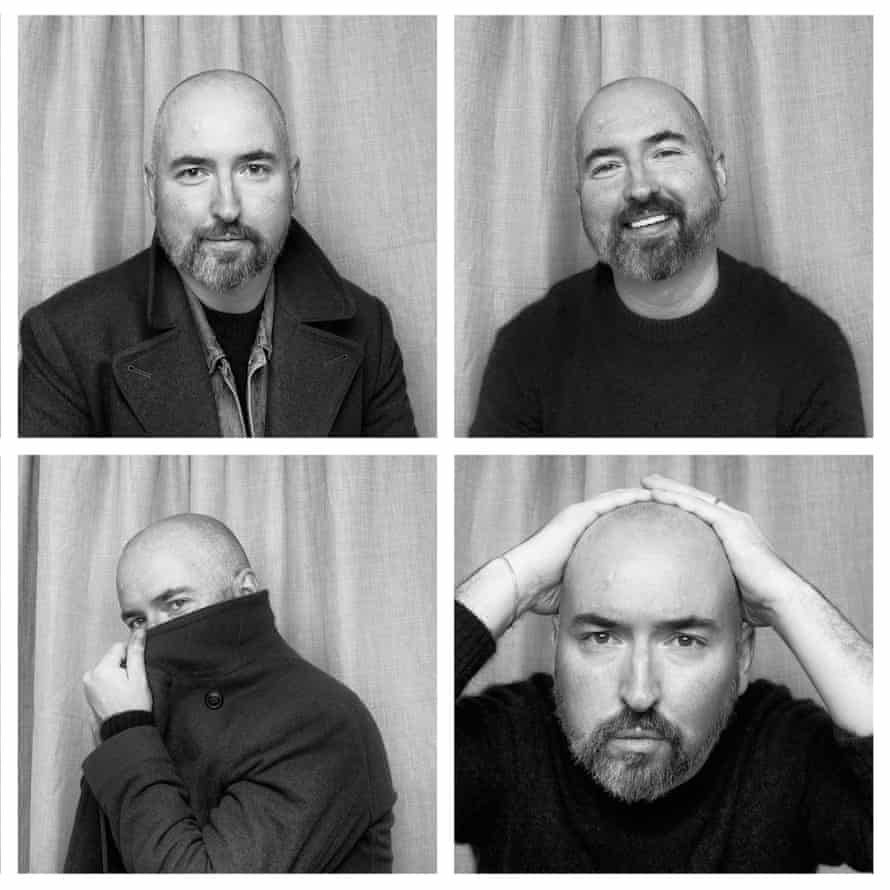

‘The best thing about being a writer is the focus that loneliness brings’

Douglas Stuart

Author of Shuggie Bain (Picador, 6 August)

Douglas Stuart was brought up on a housing estate in 1980s Glasgow. His alcoholic mother died when he was 16; he never met his father. He studied textiles in Galashiels and then the Royal College of Art. For the past 20 years, he has lived and worked as a fashion designer in New York, first for Calvin Klein, then Ralph Lauren, then as head of design for Gap. Most recently, he designed for Jack Spade. Shuggie Bain tells the story of awkward, lonely Hugh “Shuggie” Bain and his ambitious, charismatic mother, Agnes, as they try to protect each other – and themselves – amid the brutal destitution of Thatcher’s Britain.

What made you want to be a writer?

I always wanted to be a writer. Fashion has provided me with a wonderful life, but I’ve been writing now for 12 years in private, in secret, for myself. I didn’t write this book with any notion of it being published, of it even being read by someone else. What I decided when I turned 40 a few years ago was that it was time to take a sabbatical. I had dreams that were going unanswered and those were dreams of writing. So I took time out to write and showed Shuggie to a friend in publishing and the response has just been phenomenal.

If you had to sell the book in a sentence, what would you say?

It’s a love story about two souls trapped in a hyper-masculine world who are struggling to get by, to survive, to love each other.

Where do you write and what is your work schedule?

I need complete silence, which is very hard to achieve in New York as there’s construction going on around me all the time. The most important thing that I own is a pair of noise-cancelling headphones and every morning, at about seven, they go on and I immerse myself in my work. I’m an early-morning writer. Because New York is such a cramped real estate market I have to wait for my husband to stop banging coffee mugs and the dishwasher and leave for work. I get up before he gets up in the morning, then I take a couple of hours off to hang out with him, then when he goes off to work I get straight back to it.

Best debut you have read?

Morvern Callar by Alan Warner. Here was a book where I saw people like myself reflected and I could really empathise with Morvern’s desire to escape from the world she was in. It knocked me sideways.

What books are currently on your bedside table?

I’m currently reading And the Land Lay Still by James Robertson. It’s a book that’s been out for 10 years or so. I’m also rereading Young Adam by Alexander Trocchi and then also The Trick Is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway. A book I’ve just finished and loved is Lowborn by Kerry Hudson. It’s a wonderful book, such quiet grace.

Best and worst things about being a writer?

The worst thing is the loneliness, especially coming from an industry which is all about dynamic team-building, and I sometimes find myself feeling isolated, but the best thing is the focus that loneliness brings. So for both sides of the question the answer is loneliness.

What single piece of advice would you offer to aspiring writers?

Don’t fear if you don’t come from a certain background. Find what it is only you can offer the world and put that on the page.

Interview by Alex Preston

‘My ambition is to be a sort of feminist hermit crab’

Jessica Moor

Author of Keeper (Penguin Viking, 19 March)

Jessica Moor. Photograph: Sophia Evans/The Observer

Twenty-seven-year-old Jessica Moor lives in Berlin but was born in south-east London and her debut novel, Keeper, started life while she was doing an MA in creative writing at Manchester University, where she was mentored by Jeanette Winterson. A literary thriller, Keeper is a compelling, tense and pacy read, with a central character who works in a women’s refuge. Moor herself worked for a domestic violence charity for a while after finishing her BA. “It was a bit of a ‘road not taken’,” she says. “I was thinking about training to be a psychotherapist and I needed a day job that would lead to a relevant field. But I was also drawn to it because I’m very much a feminist, although, looking back, I feel like my feminism was quite underdeveloped at that point.” The role developed her thinking. “It made me feel that everything is connected, and that there is a dismissal of women and the control of women’s bodies that underpins everything… there’s an ideology behind it and the logical conclusion of that ideology is violence against women.”

‘I kept wondering about that idea: can you love someone and kill them?’

Stephanie Scott

Author of What’s Left of Me Is Yours (Orion, 21 April)

Stephanie Scott was born and raised in Singapore. She came to the UK to study English at university, where she specialised in Renaissance literature. Just as she was starting her PhD at Cambridge, she decided that she couldn’t face the idea of “being locked in a garret,” and took a job on the hedge fund desk at Lehman Brothers. Working late nights on deals, she’d dream of becoming a novelist and scan the websites of creative writing courses. She finally took the plunge, applying to study at the Faber Academy and on Oxford University’s creative writing master’s programme. “I was accepted on both and so I decided to do both, to really pursue writing seriously.” Scott’s debut, What’s Left of Me Is Yours, delves into the murky world of Japanese marriage-wreckers to tell a strange and tragic love story.

How did you come to write this book?

I read an article by Richard Lloyd Parry of the Times about a real-life crime. In that case a marriage break-up agent had strangled his lover when she discovered his true profession and threatened to leave him. The agent was arrested at the scene and confessed to police, but as he was speaking to the police he said: “I loved her, I love her still.” And it’s the humanity of that original story that drew me to it.

I was newly married at the time and was thinking a lot about love and enduring relationships. I kept wondering about that idea: can you love someone and kill them? Because love ideally requires selflessness, but then I thought perhaps there are as many different types of love as there are people.

I spent several years researching and living in Japan, visiting all the locations. I worked on the novel for years and was lucky enough to win a Jerwood award and the Escalator award. I had a lot of agent interest coming through as I worked on the draft, but I wanted to finish it on my own terms. I sent it out when it was ready and had 23 agents interested. It was a bit mad. But then I chose my agent, Anthony Harwood, and within a week of sending it out he’d secured a six-figure pre-empt [offer] from Doubleday. I started laughing and crying like a madwoman down the phone to him. It has sold in eight territories so far.

Where do you write and what is your work schedule?

I need to be at my desk in my study. I need to know what I’m writing about. A lot of the novel was drafted by just writing what I wanted without planning out where it was going but, having said that, the novel is so research-based that I had to have the grounding in place before I could begin it.

Have you been mentored or particularly encouraged by anyone? If so by whom and how?

I was taught on the Faber novel course by Louise Doughty and Louise has been hugely supportive of this novel from beginning to end. By the time it comes out it will have been 10 years in the making. She has been an extraordinary mentor. She was instrumental in my finally deciding to leave finance and focus on the book, which was a crazy thing to do at the time.

Best debut you have read?

My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite. I absolutely adored it.

What single piece of advice would you offer aspiring writers?

Persevere and believe in yourself and your project.

AP

‘Being a writer helps you make sense of everything else in your life’

Naoise Dolan

Author of Exciting Times (Orion, 16 April)

At just 27, Naoise (pronounced “Neesha”) Dolan is remarkably self-assured and laid-back about the prospect of becoming a published novelist. “It seems like a nice job to have,” she says breezily. Born in Dublin, she studied English at Trinity College but had never seen writing as anything more than “a hobby I enjoyed, like playing the piano and drawing”, until she took a creative writing course in her final year. “That was a game-changer. I came out of it pretty much saying, ‘I want to write a book’,” she says.

A year teaching English in Hong Kong provided the setting and subject matter for Exciting Times, the story of a love triangle that also explores class, colonialism, language and more, while also being frank about female sexuality. Dolan’s friend Sally Rooney (a couple of years ahead at Trinity), published the first chapter in her literary journal, Stinging Fly, and a seven-way publishers’ scrum ensued. Is she, as the industry buzz suggests, the next Rooney? We’ll see when her novel hits bookshops in April.

If you had to sell the book in a sentence, what would you say?

I think I’d say it’s about love, money and the intimate lives of three young cynics living in Hong Kong – and I would do my best to keep a straight face.

Where do you write?

I try to put as few conditions as possible on what needs to happen for me to be able to write because I find, in practice, that just turns into excuses for me not to write. Ideally, I’m somewhere where there’s not too much going on in the background. But I have to take a lot of trains because I don’t fly [due to the climate crisis], so I’ve trained myself to be able to write in that situation, too. Otherwise I just lose a day.

Is there anything you need to work?

I’m completely dependent on coffee but that’s not writing-specific: I’d be a shell of a human being without it.

What books have inspired you to be a writer?

I always loved the Victorians. They were pretty much a special interest since my early teens, which is why I did a master’s in Victorian literature at Oxford after I’d been to Hong Kong. I think of all of them, Dickens has inspired me the most because he has got what very few people have, which is the ability to construct this compelling story but also to write absolutely wonderfully at a line-by-line level. On any page of Dickens you’ve got a really unusual cluster of words or something really funny or true, but you really want to find out what happens next as well.

What are the best and worst things about being a writer?

Best is having a book always humming in your mind. It’s really nice, even when something miserable happens in your day, to be able to think, maybe I can work that into the story. It helps you make sense of everything else in your life. Worst is people expecting you to be precious about your book and treat it like your baby, because I am not sentimental like that at all. For my mother, for instance, the idea of me being edited was this offensive thing, while I’m like: “Yeah, let’s get the scalpel out, let’s fix it.”

What single piece of advice would you offer to aspiring writers?

Ignore the whole social performance of being a literary person. That thing of feeling you have to go to book launches or that all your friends have to be writers. That stuff is irrelevant to writing a book and it can take up a lot of your time and money if you let it. It’s not what makes you a writer.

Interview by Lisa O’Kelly

‘I thought, wouldn’t it be great if I could write something that I want to read?’

Louise Hare

Author of This Lovely City (HarperCollins, 12 March

• This article was amended on 26 January 2020 to note that the list includes British and Irish authors, and on 31 January 2020 because an earlier version incorrectly referred to Richard Lloyd Parry of the Financial Times. He writes for the Times.