Fun Home creator Alison Bechdel on turning a tragic childhood into a hit musical

The acclaimed graphic novelist, who gave the world the famous movie equality ‘test’, on exposing her family, appearing in The Simpsons and why comics are her Trump therapy

Rachel Cooke

Sunday 5 November 2017 08.00 GMT

L

ast summer, Alison Bechdel returned to the small Pennsylvania town where she grew up (population: 700) to see a production of the musical based on her 2006 graphic memoir, Fun Home – a comic that, to sum it up rather brutally, tells the story of how her closeted gay father killed himself a few months after she came out as a lesbian. “It was super-surreal,” she says. “It was the same theatre where my mother would do her amateur dramatics and my father was on the board. I was a little afraid. I felt anxious, like, oh my God, I’m going to see all these people and they’re going to be pissed off with me. Because there were people in my hometown who did not think Fun Home was a good thing. They thought it dishonoured my family.” So how did it go? Even now, she sounds amazed. “There was this great warmth that I just hadn’t expected. I had thought I was going back to 1977, but the place has changed. It has… evolved.”

Why she should find this surprising is slightly mysterious. Hasn’t she evolved too, down the years? “Yes! Fun Home is a midlife document for me and I am trying to move on.” She laughs. Still, the feeling persists that, just lately, she is living a life that is not quite her own. Before Fun Home, she had worked in relative obscurity; fame, let alone fortune, seemed unlikely ever to be on the cards. But with the book’s acclaimed publication, its appearance on the New York Timesbestseller list and then the musical, all that changed. People recognise her on the street now. Last month, she even had a cameo in an episode of The Simpsons (in “Springfield Splendor”, Lisa Simpson writes a graphic memoir about her childhood called Sad Girl, which Marge illustrates; when the book is a hit, Bechdel, Roz Chast and Marjane Satrapi appear alongside them on a panel at a comics’ convention).

“I could never have foreseen it,” she says of the musical, which opened on Broadway in 2015 and went on to win five Tony awards (it will be staged at the Young Vic in June). “I only agreed to the idea of it at all because I didn’t know what I was getting into. It seemed harmless enough. I had turned down a movie on the grounds that if it wasn’t good – and the chances of that being the case were very high, because most movies aren’t good – it would be awful to have it out there in the world, this terrible version of my most intimate history. That was easy. But a musical? I was naive. I thought: if it’s a bad musical, it will just disappear.” She pauses. “It never occurred to me that it could be very bad and very successful. I didn’t consider that. Anyway, it wasn’t. Bad, I mean. So I’m really glad I said yes. They [Lisa Kron, who wrote the book, and Jeanine Tesori, who wrote the music] made something beautiful out of it.”

So much time passed between her agreeing to the idea and it becoming a reality she’d almost forgotten they were working on it at all. (In the interim, she had been awarded a $625,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant and had published a second memoir, Are You My Mother?) “After a while – it had been years at this point – they sent me a script and a soundtrack. I was deeply moved. That first moment of hearing it: I just felt it was this great gift. I felt seen.” As something of a connoisseur of therapy, she wonders if someone shouldn’t develop a whole new branch of lyric-based treatment: “I think there should be a kind of therapy where people hire playwrights and composers to make musical theatre of their sad childhoods.” Do comics and musicals have something in common? It strikes me they can share a weirdly direct route to the human heart. “Yeah. I wonder if it is because of the way two registers collide. In a musical, you have drama and music. In comics, writing and pictures. They operate differently, but with the same power.”

Of course, loving what Kron and Tesori had done didn’t make the prospect of the musical being staged any less fraught. Her mother, then still very much alive, was only just recovering from the publication of her daughter’s memoirs (the subject of Are You My Mother? is Bechdel’s difficult relationship with her). “It’s kind of monstrous to do what I did, to expose your family like that,” says Bechdel. “But my father was dead. My mother had to live with all her friends and even strangers knowing this intimate stuff about her life. She was a reticent person. She wasn’t happy about it.”

But then her mother died, five months before the show opened. “I have mixed feelings about that. I don’t think she could have handled seeing it. That would have been too painful for her. There was a possibility she could have seen a workshop, but she would only do that if she could be the only person watching, so it never happened and perhaps that was meant. But I do kind of wish she’d gotten to see the great reviews it had.”

In 2014, in an effort to process her feelings about the musical, Bechdel published a short strip in which she reveals how, thanks to a diary muddle, she missed its opening night off Broadway in 2013, finding herself instead in a hotel room in rural Ohio, where she spent her evening refreshing the New York Times theatre page until its review appeared. “It was a startling, unqualified rave,” she writes in the final frame. “My parents, who had met in a play, would get to go on living in one.”

Has the musical changed how she feels about her memoir? No. It is life itself that has had most impact on that score. “My perspective on that story has changed,” she says. “I’ve got so much more information now about my family and what happened. I’ve got more pieces of the puzzle.” But that isn’t to suggest that she hankers to go back, to augment or edit what she set down then.

“In some ways, it [the new information] would have made it a less interesting book. Not knowing everything is sometimes a good thing in a memoir: a mystery or quest is better than laying out all the facts.” Does she still feel that writing it helped her psychologically? “Yes, I do, though when young people ask me if it was cathartic, and I say ‘yes’, they don’t really know what I mean. They just want to go home and write their diaries and feel better themselves. I wrote diaries, too, for years. But I also did therapy for years. And I pushed myself to engage with my family in an honest way for years. And all that stuff was part of writing the book. I remember being so excited when I read about Virginia Woolf getting her mother out of her head by writing To the Lighthouse. I felt the same after Fun Home. I had been haunted by my father and I no longer was. I took him off my hard drive. He was using up all my RAM.”

She lives with her partner, Holly Rae Taylor, an artist and compost maven, in rural Vermont. “I used to be here all the time except when I had traumatically to go out and do a book tour or speak at a university. But now that’s completely reversed. The past four years have been crazy. I’ve only been home for a month at a time and it’s making me insane. I love a quiet life. I don’t need a lot of social stimulation.” She lifts up her computer, the better to show me her basement workroom (we are speaking on Skype). “I live in the woods,” she says. “Look, can you see?” The camera pans around: autumn foliage, drawing board, bookshelves, desk. “I try to take Sundays off. That’s a new development.” What she says next is at odds with her smile, which is pretty wide. “It’s my personal craziness,” she tells me. “I don’t feel I deserve to exist unless I’m working.”

Again, this isn’t to say that she wishes Bruce Bechdel, with his temper and his obsessional interest in frilly 19th-century interiors, had been different (he died beneath the wheels of a truck in 1980, at the age of 44). “Someone once asked me: would you rather have had a happy childhood or to have written this book? And I didn’t even have to think. I would take the book and with it my own bizarre way of relating to the world, a way that I learned from my moronic family. Of course I would!” Ambivalence, as journalists have often pointed out, is Bechdel’s default mode; when she draws herself, she often appears uncertain, a frown etched on her brow. But when she talks about the connection between her upbringing and her work, she sounds straightforward, enthusiastic, you might say. One thing her parents taught her, in all their unhappiness, was the importance of art in its widest sense and of not letting very much get in the way of one’s pursuit of it (while her father, the great “artificer”, sublimated his desires, devoting himself instead to the restoration of the family’s gothic revival mansion, her mother took refuge in music and amateur dramatics). Left to her own devices, Bechdel, in turn, is inclined to spend all day, every day, pencil in hand.

Some see Fun Home as having been a turning point for graphic novels; following its success, they grew dramatically in popularity and began to be taken more seriously by the media. Bechdel, though, doesn’t entirely buy this. “It’s interesting that you think the terrain changed after it came out,” she says. “I feel like timing was a huge part of its success; if it had appeared a few years earlier, I don’t think it would have gotten the purchase it did within the culture. I don’t think people were ready to read that story before. Howard Cruse, who founded Gay Comix in the late 70s, was a huge mentor of mine. I always loved his work and his strip inspired Dykes to Watch Out For [which she wrote and published in the alternative press between 1983 and 2008]. In 1995, he brought out this beautiful book [Stuck Rubber Baby] about his life in the civil rights movement. He’d devoted years of his life to it, but it didn’t cross over. People weren’t ready to identify with a gay hero. That changed in the next decade.”

But perhaps, too, her book had a particular appeal for mainstream critics. “I was lucky to have regular critics review it [as opposed to comics specialists], which they did maybe because it had a literary strand.” While some graphic novels falter when it comes to words – relatively few cartoonists are truly good writers – Bechdel’s prose is richly precise; the New York Times reviewer admitted she had sent him to his dictionary to look up such words as “humectant”, “scutwork” and “buss”. It also bulges with references to, among other writers, Proust, Joyce, Camus, Colette, Radclyffe Hall, Scott Fitzgerald, even Kate Millett, allusions that cleverly modulate its taboo-busting heart, its outstanding weirdness. (Bruce Bechdel, a high-school English teacher, was a part-time undertaker; the book’s title refers to the family nickname for the funeral home he inherited from his father, an establishment whose viewing parlour Alison was sometimes required to vacuum). A decade on, it still feels pioneering, a comic that seeks determinedly to take the form in new directions.

Bechdel, who was born in 1960, began drawing, as most of us do, as a child. But she kept going: even when she was little, she wanted to be a cartoonist (or a psychiatrist, jobs that, she once said, she had conflated thanks to all the analyst cartoons in the New Yorker). After Oberlin College in Ohio, where she studied art history as well as, among other subjects, German and Greek, she moved to New York, taking on the kind of boring jobs that allowed her to draw. Dykes to Watch Out For was born: a funny, knowing strip about a gang of more-or-less radical lesbians in which Bechdel appears as a character called Mo who resembles a guilty-looking teenager (and also Tintin).

“I spent a long time working very hard and making no money,” she says. “It was increasingly disheartening. All the places that published my comic strip were disappearing. The gay bookstores were closing, the queer newspapers were folding. My income, which in my 30s had been almost enough to live on, was suddenly not quite enough for someone in their 40s. If Fun Home had not caught on, I would have had to stop and do something else.”

How daring did it feel to be working on Fun Home? The answer is: very. What a lot she hoped to achieve. “Luckily, I had clarity about what I wanted to do and that carried me through the very reasonable doubts I also had. It helped me to overcome the feeling that this was outside my capability. It was such a huge project: six or seven years of drawing and excavating. It was sort of like living in a trance. I had to do everything I could to figure it all out.” That she pulled it off, however, had little impact on her ability to repeat the trick. Are You My Mother?, which scrutinises her relationship with Helen, with help from the writing of Virginia Woolf and the psychoanalysts Alice Miller and Donald Winnicott, didn’t appear until 2012; now she’s running late with her new memoir, The Secret to Superhuman Strength.

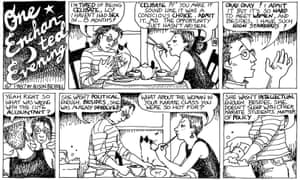

Thanks to Trump, too, her dykes have returned – though perhaps more in sadness than in triumph. “They’re my own personal therapy for the administration,” she says. “When Obama arrived, I stopped. I thought, thank God, I can take a break from this. I’m not a naturally political person. People would ask me: I wonder what your characters would think about this or that? And I was, like, I don’t know and I don’t care. I don’t carry them with me in my head. But as soon as Trump was elected, they came back to me. They were always a way for me to make sense of the world; they would have slightly different political positions and arguments could be worked out. So now I’ve done a few more.” In the most recent, Mo tells her conservative brother, Scott, it’s as though Breitbart broke his brain. “You poor little deep state dupe,” he replies.

“I was supposed to turn it in a year ago,” she wails. “I know it sounds diva-ish, but thanks to all the interruptions, I haven’t been able to get into the deep state of concentration that I need to write and think clearly.” What’s it about? “It’s about physical fitness and… mortality – and that’s the hard part, the mortality. It’s about what it’s like to live in an ageing body, knowing you’re going to die. The exercise part [Bechdel, who has a black belt in karate, has long been keen on fitness] is like the sugar to make the medicine go down, the medicine being all these big questions of life.” She pulls a comically agonised face. If it’s no use looking back, nor is it, you gather, particularly easy to move forward: “I have to feel whatever I’m doing is impossible, otherwise I will just not do it. That’s what motivates me.”

Thanks to Trump, too, her dykes have returned – though perhaps more in sadness than in triumph. “They’re my own personal therapy for the administration,” she says. “When Obama arrived, I stopped. I thought, thank God, I can take a break from this. I’m not a naturally political person. People would ask me: I wonder what your characters would think about this or that? And I was, like, I don’t know and I don’t care. I don’t carry them with me in my head. But as soon as Trump was elected, they came back to me. They were always a way for me to make sense of the world; they would have slightly different political positions and arguments could be worked out. So now I’ve done a few more.” In the most recent, Mo tells her conservative brother, Scott, it’s as though Breitbart broke his brain. “You poor little deep state dupe,” he replies.

It was in Dykes to Watch Out For, famously, that the rule that later became known as the Bechdel test first appeared in 1985, when one of her characters told another that she only goes to a movie if it has two women in it who talk to each other about something other than a man. (“Pretty strict,” says the second woman. “No kidding,” says the first. “The last movie I was able to see was Alien… ”) Bechdel, somewhat nonchalantly, has always insisted that it was the idea of her friend, Liz Wallace, and that she herself doesn’t even care about movies. But today, she sounds wholehearted in her enthusiasm. The test featured in TheSimpsons episode, which got her “excited” about it all over again. “It is a wonderful thing,” she says. “I’m very happy my name is associated with it. The culture needs it right now.” We talk about Harvey Weinstein, and she shudders.

Before our conversation ends, she tells me which comics she has enjoyed recently. “Well, Hostage [Guy Delisle’s account of the kidnapping of a French aid worker in Chechnya] was amazing,” she says. She thinks for a moment, and then – “Wait! I’ve got to look” – leaps up. When she returns she’s bearing Tenements, Towers and Trash, Julia Wertz’s alternative graphic architectural history of New York. “Now this is really ambitious,” she says, turning its pages. Ultimately, though, what she still loves to read most of all is autobiography. Narcissism, that comic drama in which every one of us has a leading role, is both her great subject and, you might say, her hobby. Down and down she digs, deep into herself, after which, by way of a break, she likes to ponder the excavations of others in all their ineffably touching and ridiculous glory.

No comments:

Post a Comment