|

| Michelle de Kretser |

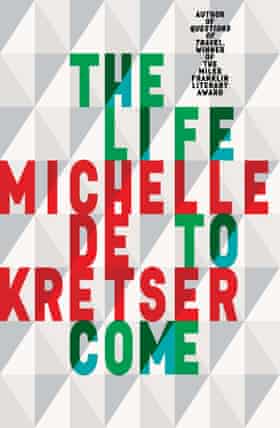

'We are not very caring’: Michelle de Kretser on Australian society

In her new novel The Life to Come, the Miles Franklin-winning author critiques Australia’s character, and the boom that made us bad

Brigid Delaney

Fri 10 Nov 2017 21.30 GMT

Children of Australia’s long boom – who travel the world only to complain about lack of good coffee, who signal virtue by retweeting an asylum seeker story, who couldn’t imagine living in a house with only one bathroom, who are “really into food” – may find Michelle de Kretser’s new book an uncomfortable read.

The Life to Come is a novel in five sections that focuses, in part, on the lives of Australia’s upper middle-class progressives. We meet Celeste, an Australian now living in Paris; Ash, a Sri Lankan academic in Sydney; and Pippa, a moderately successful novelist.

|

| Michelle de Kretser: ‘The reason I feel free to critique us is that I am us.’ Photograph: Fred Kroh |

These are people who attend writers’ festivals, carefully curate their identity on social media, and make creative salads from seasonal ingredients.

These are people who would never vote for Pauline Hanson and are appalled at Australia’s refugee policy, but de Kretser gets under their skin and exposes the things they don’t want others to see: paternalism, a thin skin, materialism, philistinism, and the sort of wanton innocence enjoyed by those who have never experienced real suffering.

“There was one early reader who said I have a really superior attitude to Australians. It made me think she didn’t think I was Australian,” de Kretser tells Guardian Australia. “The reason I feel free to critique us is that I am us. The best response any writer can hope for is to make your readers think.”

De Kretser, a Miles Franklin-winner, was born in Sri Lanka, raised in Melbourne, spent time studying in Paris and is now based in Sydney. Her book is a big, juicy, enjoyable novel that has plenty of humour – but it is the almost satirical observations about Australia and this particular moment that really stick. After all, it’s usually Australia’s chattering classes that do the critiquing; it is more unusual for them to be the subject of such a sharp and nuanced portrait.

Take one moment from the book, for instance, when Celeste’s French mother explains Australians to her:

“Australians are hard-working and very successful. They are suspicious of their success and resent it. They are winners who prefer to see themselves as victims. Their national hero, Ned Kelly, was a violent criminal — they take this as proof of their egalitarianism. They worship money, of course.”

In another scene, Celeste asks her mother, “Why do Australians always go on about food?”

“Because they live in a country of no importance.”

Ouch!

And sure, Sydney is beautiful, Ash observes, but “why didn’t Australians heat their houses?”

When I meet de Kretser in a (warm) café in Sydney’s inner west, she is keen to talk politics. Manus Island and abandoned refugees have been in the news all week and she’s appalled, particularly at the Labor party, which she says has not provided opposition to offshore detention.

“We are not very caring as a society – although there are plenty of caring individuals – and part of this is that Labor has just really given up on a lot of its responsibilities.”

She is cheered by the recent success of Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, and thinks a radical realignment of values is necessary if our society is to get back on track.

“The world has embraced neoliberal politics. Since the collapse of the Soviet union, there has been a move away from leftist politics, which is being seen as loser politics – all those old social justice things such as free education and universal health care.”

Although The Life to Come is not a political novel, it is a book that captures the political, social and economic zeitgeist. The beautifully drawn and complex characters are all creatures of the time.

“I’m not writing directly about Australia and its politics, but I am interested in self and the bigger picture,” says de Kretser, who moved to Australia in 1972 when she was 14.

“Our moment in history – these things determine the course of our lives. I would have never had a university education if I had been born now. I’m always conscious of how things are changed by external forces.”

In the novel, de Kretser also explores the experiences of Australians abroad. As her character Celeste observes, wealthy Australians travel carelessly, “setting out from home ... like fortunate children [who] had expected to be loved”. Writers living in France on Australia Council grants complain that no one in Paris has heard of them, and that “the chlorine levels compared unfavourably with Australian pools”.

Another character Pippa is saving up to travel with her boyfriend next year; her dismissive housemate George describes her speaking “of ‘Asia’, of ‘Europe’, collapsing civilisations in the sweeping Australian way’’.’

The book deals with racism in Australia, too – but the sort you might find from someone on the left, who would be shocked at being labeled racist at all.

“It’s not the overt racism of someone abusing a woman in a hijab on a train. With those people we can see their workings very clearly,” de Kretser says. “But there are a whole lot of people – progressive, lefty people – people who generally see themselves as a good people, who will display tolerance and paternalism thinking they are not racist.

“They expect, for example, that refugees or migrants show a certain gratitude. It’s a subtle undercurrent [of racism], but it’s there.”

To truly banish racism, she says, “the tone – in a workplace, a family, an institution – must be set from the top.”

The Life to Come is set during Australia’s boom. Mining money is funding mega mansions in Perth, with parents’ retreats and swimming pools. There’s money left over for frequent overseas holidays and lavish restaurant meals; even the writers are rich.

“One of the problems with Australians having so much money is they don’t have a memory of what it is like to go without. What is taken for granted now was once considered luxurious, even excessive,” says de Kretser.

And it is this over-the-top materialism and the lush experiences that form fodder for the social media feeds of de Kretser’s characters. That, and virtue signalling.

“Curating of the self – people do it all the time in the real world as well,” de Kretser says. She goes into faux-gushing mode, mimicking a tweet: “Oh gosh – aren’t I lucky to have won this award. So humbled! So blessed!”

But even on Twitter, we contain multitudes. “In the same person’s feed, maybe days have elapsed, but you are reading one after the other: you can be reading about Manus, then you’ll be reading about how their morning coffee wasn’t up to scratch. It’s really weird stuff.” (De Kretser has an Instagram feed, which includes mostly “daggy photos” of her dogs.)

While many of the strands of The Life To Come sound like they stand in severe judgment of Australians, it is actually a very funny read – and even the most annoying, or sexist, or prejudiced characters have redeeming qualities.

“Our view of other people is only ever partial. We are only ever see certain selves. It’s fun to create a self and act out a best version of this self,” de Kretser says. “That is what we all should be remembered for: our best self.”

No comments:

Post a Comment