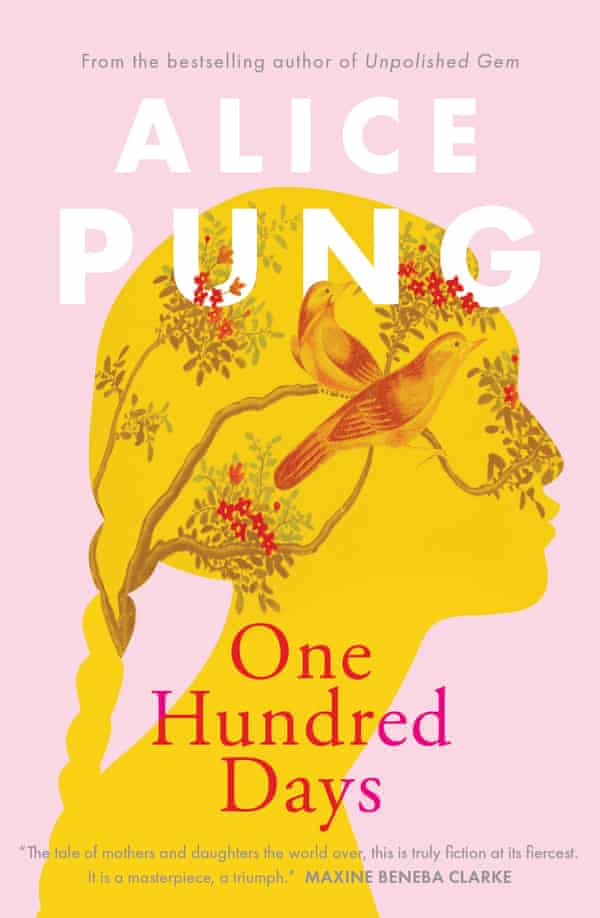

Pung’s new book One Hundred Days is set in the mind of a 16-year-old whose mother traps her in their commission flat after she falls pregnant

The 25 best Australian books of 2021

Sat 29 May 2021 21.00 BST

When Alice Pung was a teenager growing up in the suburbs of Melbourne, she had friends at school who got pregnant and vanished. “I never saw them again, and I wondered what happened to them,” the author says.

This laid the groundwork for Pung’s new novel, One Hundred Days. Set in the 1980s, it follows 16-year-old Karuna, who falls pregnant after a whirlwind romance with a tutor at the local community centre.

Incensed and ashamed, Karuna’s overprotective mother holes her up in their commission flat for 100 days – a postpartum confinement tradition in many cultures.

Yearning for an escape from her suburban isolation, the teenager loses herself in Walt Whitman’s poetry and copies of Reader’s Digest. The book is written from Karuna’s quietly furious perspective, addressed to the baby growing within her as she feels her own life vanishing before her.

Pung’s own mother wanted to impose the confinement tradition for the author’s first pregnancy, she says – but the baby was premature, so she had to go to hospital daily. (“I got the advantages – she made all the great food, but I didn’t have to be trapped for a whole month at home,” Pung remembers.)

When we meet for coffee in Carlton, her six-month-old baby is strapped to her chest – Pung’s third child but first daughter. The complexity of motherhood is a key aspect of One Hundred Days, which the author says comes from “having my own kids and being a daughter myself”.

Complicated child-parent relationships, especially within particular cultures, are a ripe area for literary exploration. Pung and I discuss the challenges of communicating thorny cultural differences to readers who have westernised expectations of child-rearing – Rebecca Lim’s young adult novel Tiger Daughter is another recent example.

“The way many immigrant children were brought up, the parents give you orders for your own good. It’s a different relationship, that some readers might consider emotional abuse,” Pung says. “I wrote this for people like us, but also for every young person or child who feels oppressed by a parent who has different beliefs.”

Karuna’s biracial identity is also an important thread in the book, which captures the pain of feeling caught between cultures. Throughout the novel, the teenager idealises her absent white father, who she perceives as a symbol of a freer existence. Pung delicately teases out the common experience of a daughter resenting her mother and looking up to her father, made even more complex by fraught racial dynamics.

“In Anglo culture, the parents try and cultivate your independence so that when you’re 18, you can stand on your own two feet and find a life for yourself, whereas in quite a few immigrant cultures I don’t know when that moment of adulthood is, because you’re always a child to your parents,” the author says.

One Hundred Days is Pung’s first literary novel marketed towards adults, but like her celebrated 2014 young adult book, Laurinda, it takes the reader into the mind of a teenager. She compares it to Vivian Pham’s 2020 novel, The Coconut Children – both books defy adult literature conventions by presenting a raw yet sophisticated view of adolescence and life from a teenage perspective.

“I don’t see a distinction. I grew up with young people who had very adult responsibilities – teenagers can deal with tough things,” Pung says. “I wrote it for a teenager. If I started writing it for an adult, the perspective would not be as immediate.”

Another commonality with Laurinda is the representation of class issues, which play out in the schoolyard and community where Karuna lives. Her mother works multiple low-paying jobs to pay the bills, and Karuna works the same jobs for free to help out. The impending arrival of the baby poses great financial strain.

Pung herself grew up working-class in Melbourne’s west. She came to Australia in utero with her Cambodian refugee parents, and charts her family’s history in her memoirs, Unpolished Gem and Her Father’s Daughter, published in 2006 and 2011 respectively. Her own background informs the characters and stories she writes. “Class is in my books because it’s impacted my life sometimes more than race,” she says.

The main relationships in One Hundred Days are between Karuna and her mother, Karuna and her baby, both women and the baby – and, most importantly, Karuna and herself. It’s a coming of age of sorts, as the young woman faces impossible challenges and emerges with new understandings about motherhood, friendship, family and life.

Pung is a lyrical writer who trades often in highly decorative prose, but she borrows from Whitman’s Song of Myself to top and tail the book with a fitting quote that’s sublime in its simplicity: “I celebrate myself.”

One Hundred Days by Alice Pung is out on 1 June through Black Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment