|

| Ásta Sigurðardóttir |

CLEOPATRA’S POISONED CUP

Icelandic writer Ásta Sigurðardóttir had a fondness for self-presentation that took her contemporaries’ breath away. All her short stories reflect a tension between, on the one hand, the longing for normality, security, and bourgeois acceptance and, on the other hand, rebellion, a need for freedom, and a deep-seated rejection of bourgeois values.She loved to perform, but no-one else should write her roles for her. Journeying is a recurrent motif in Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s texts, and her characters are alone, in both a physical and an existential sense. Her late texts lack the intensity that characterised her first short stories. The pride, the self-assertion, the queenly arrogance are gone. The gaze is dull, self-hatred is dominant. There is no longer anything worth describing.

A Russian violinist is due to play at Hotel Borg, a restaurant that tends to be jumping, where it is usually smoky and noisy, and full of lively erotic transactions. The restaurant is a meeting place for the young men and women of 1950s’ Reykjavík, a town that underwent drastic expansion during both the war and the post-war years. The oldest generations in town have just about lost track of who is who. But everybody knows who Ásta Sigurðardóttir is.

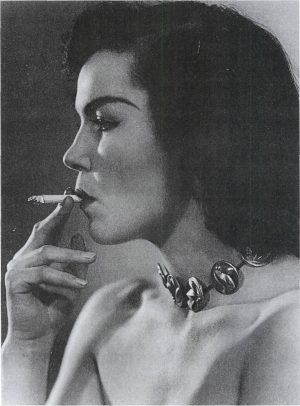

Ásta Sigurðardóttir (1930-1971) is the female bohemian who hangs out in cafés along with the young artists. She is an author, a visual artist, and a model. She is a young woman with a very dubious reputation. She is never very far away when things heat up at Hotel Borg, but this evening there will not be any dancing. There is to be a concert. People sit, somewhat solemn and silent, at their tables and wait for the Russian violinist.

»“Then a woman comes into the room. An enchanting woman one cannot help looking at. At first, no-one recognises her. A cosmopolitan like that is a rare sight in Icelandic restaurants.

‘Is it Ásta?’ people whisper, ‘can it be true?’ It is Ásta. Dressed in a sea-green satin dress she has sewed herself. Her black hair is up in a bun, and around her eyes is grey eye-shadow and discrete black eyeliner. The powerful Cleopatra lines are gone […]

She waits for the violinist … Everyone waits for the violinist …”. And when he comes, he plays only for Ásta.

This soap opera may be found in Friðrika Benóný’s monograph on Ásta Sigurðardóttir, Minn hlátur er sorg (1992; My Laughter is Sorrow). It depicts to perfection the fondness for self-presentation that took her contemporaries’ breath away. She was scornful and contemptuous of the norms of the petit bourgeoisie, and openly provoked them. She could nevertheless not stand their obvious condemnation of her lifestyle. All her short stories reflect a tension between, on the one hand, the longing for normality, security, and bourgeois acceptance and, on the other hand, rebellion, a need for freedom, and a deep-seated rejection of bourgeois values. She loved to perform, but no-one else should write her roles for her.

THE OUTSIDER

Ásta Sigurðardóttir became a star overnight with her first short story “Sunnudagskvöld til mánudagsmorgun” (Sunday Night to Monday Morning), which was published in the journal Líf og list (Life and Art) in 1951.

The reader follows the protagonist of the short story as she is born or gives birth to herself in the text. The story is told in the first person, and the narrator is a young woman called Ásta. She is an uninvited and undesired guest at a party or nachspiel held in a bourgeois home one Sunday evening. Her drunken, perverted point of view expresses a chaotic self-perception, the focus is on details rather than the whole picture, pain and anxiety are expressed in metaphors about falling and drowning small animals in a bottomless swamp. The sense of anxiety continues into the second part of the story, which depicts a nocturnal wander through the streets of town, but here the ironic tone of the text becomes more obvious.

A nice old man happens by the woman, invites her home, and tries to rape her. The attempted rape is partly due to the main character’s naivety and innocence, which serves to contrast with, and accentuate, the rapist’s misogyny and vulgarity. The grotesque course of events comes to a halt when the woman gives out “a piercing howl that echoed gently in this large house. I had never heard such a scream”. The scream frightens the woman just as much as it does the man. “‘Wha-what were you going to do to-to me? I thought you would be as nice as daddy.’

“The tears streamed down my cheeks. He hardly understood what I was saying, but the foaming lips moved and a strange expression came onto his fat face – it looked as though he was going to cry.

“I took pity on him, to such an extent that I forgot my own misery … I brought misfortune with me wherever I went. There I came as the Devil herself, and tempted this man who looked like an apostle and was usually quite certainly decent.

“Had he perhaps not been good to me?” The story maintains this ironic tone through the night’s other ‘adventures’. It is a mistreated but nevertheless victorious young woman who emerges, at the end, from the story.

Journeying is a recurrent motif in Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s texts, and her characters are alone, in both a physical and an existential sense.

In one of Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s most impressive short stories, “Frostrigning” (Frosty Rain), most of the story takes place during a grotesque journey. A man travels with his wife’s body through a marsh, where the surface of the earth continually threatens to give way and swallow the horse, the man, and the woman he has killed.

The narrator has, however, not asked for their attention. She is at ease with herself and her inner world, which is continually presented as a counter-image to what is socially ‘correct’ and to the bourgeois order.

The narrator sees the rich colours of the town – they become, from her perspective, an expressionist painting. She hears the music of the rain – its rhythm becomes a magnificent symphony, which she listens to with delight. She feels the lush life of the grass, the scent of the earth, and the warmth of the sun when it shines forth. Her sensuous, soft, and imaginative femininity confronts the rigid bourgeoisie, which has the law on its side. The tension between self-assertion and self-hatred, which characterises so many of Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s texts, is in this story carefully balanced on the edge of irony, as is the case in other of the short stories she wrote when she was in her early twenties.

Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s first book was in fact a special edition of the novella “Draumurinn” (1951; The Dream). “Draumurinn” is told in the first person, and the narrator is a young woman who has dreamed about a work of art. A work of art growing inside her. She is pregnant. The father of the child rejects her and wants her to have an abortion. ‘People’ also react with hostility, and look with contempt at her swelling belly.

The second part of the novella consists of a dream. In the dream, the narrator is just about to eat some hot, boiled potatoes that are not her own. Then a child suddenly appears next to her, and she recognises it. It is her own child. She takes it on her lap and is about to feed it, but the food is swept away by someone and the child begins to cry. The narrator thinks it is God’s hand that has removed the stolen food. She tries, without success, to appeal to God’s goodness. Then she becomes angry and attacks the “someone”, and finds out that it is not God but the Devil.

The dream becomes a nightmare. The narrator is paralysed. The spell can be broken, and she can regain her strength, only by saying a particular word, but she cannot remember the word. The creature goes for the child, right in front of her eyes, and tears it limb from limb. When the creature is finished with its horrible enterprise, it pushes the veil to one side, dries its bloody hands, and smiles at the narrator. And the narrator’s heart stops:

“I recognised it all so well – the green satin dress, the long red nails, the expression around the mouth, which combined the Lord’s simple smile with the Devil’s sly grimace – the smile in the mirror! It was I who smiled”.

In the last part of the story, the narrator wanders the streets drunk. People’s condemnation, their scornful words and laughter, rain over her, despite the fact that she has had an abortion, has “accepted her punishment”, and has asked for forgiveness. Her dress is bloody. The blood begins to run down her thigh, and in the story’s closing sequence she drops down by a fence and tries to pray. But she has been stripped of language, and her crying prevents her from saying a single word.

In Egyptian mythology, the eye was Osiris’ symbol. And the image of the eye, that is, the oval lines with the circular pupil in the middle, was called “the sun in the mouth”. The pupil, the sun, represented the creative, life-giving word. The first thing the Devil attacks in “Draumurinn” is the child’s hair and large eyes. The eyes that should “mirror all the greatest beauty in the world”.

The novella is obviously symbolic, and it is possible to read it as a metanarrative about women and creativity. The narrator dreamed, through the child, of being able to transform an inner beauty into an external reality, of showing others her riches, and of receiving for them an other’s boundless recognition and love. But her feminine desire, her need for art and creativity, has been condemned and forbidden before it has even manifested itself. It is the narrator herself who has taken it upon herself to carry out the ‘people’s’ sentence, and to divide herself up in order to play all the roles of this social drama – madonna and whore, God and devil, judge, executioner, and her own victim.

The sadomasochistic game becomes even more complex in the short story “Dýrasaga” (A Story of Animals), which is about a man who frightens his little, six-year-old stepdaughter out of her wits by telling her, over and over again, the same awful story. The story concerns a large animal that chases and kills a small animal for sport. The little girl in the story rebels against the psychological torture she is made to endure. The father is angered by the message he receives from the daughter, and she wins in a way, but the game is lost anyway.

The narrative perspective of the text changes constantly, but it clearly identifies with the little girl, especially at the end when she realises she has been sacrificed. But whose victim is she, when all is said and done? The stepfather’s? Or is she a victim of the author’s sorrow and anger? Is it perhaps the stepfather who is the author’s victim? Or is it the reader? Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s impassioned and woeful stories are a textual universe criss-crossed by multiple escape routes.

POISON

One of Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s last short stories is called “Fegurðardrottningin” (The Beauty Queen). It was first published in the collection Sögur og ljóð (Stories and Poems), in 1985. It is a short, unhappy story that takes place in an untidy room, in which a middle-aged alcoholic thinks back on the high point of her life, the evening she was pronounced “beauty queen”. She has only existed in the gaze of others. This is what the mirror now tells her:

“She could only stare at herself – without wanting to. The mouth was toothless, sunk in an ugly grimace. The eyes were dull, and there were bags under them. The eyebrows were thick and colourless. It was a long time since she had done anything about them. And the skin! The surface was like an old orange, and the colour was like a rotten yellow apple. Her face was dirty, and her neck had blue marks on it. And the first wrinkles were visible. What a disgusting sight!”

This is a dehumanised picture, a picture of a thing, of rotting fruit. As is the case with other of Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s late texts, this text lacks the intensity that characterised her first short stories. The pride, the self-assertion, the queenly arrogance are gone. The gaze is dull, self-hatred is dominant. There is no longer anything worth describing.

Ásta Sigurðardóttir drank antifreeze and died at the age of 41.

Ásta Sigurðardóttir published her collection of short stories Sunnudagskvöld til mánudagsmorgun (Sunday Night to Monday Morning) in 1961. Many people had great expectations for her writing, but she had become an alcoholic. She got married and tried desperately to establish a respectable life as a poor, stay-at-home housewife and mother of six. She could not. Both home and marriage were dissolved, and all the children were put into care.

https://nordicwomensliterature.net/2011/11/16/cleopatras-poisoned-cup/

No comments:

Post a Comment