|

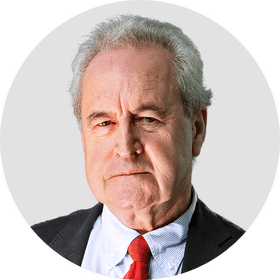

| John le Carré Illustration by T.A. |

John le Carré remembered by writers and friends: 'He always had a naughty twinkle in the eye'

Part One

Margaret Atwood, John Banville, Tom Stoppard, Ralph Fiennes, John Boorman and more pay tribute to a master who transcended the limits of spy fiction

John Banville, author

We met for lunch one rainy day at the end of last summer, in an excellent but eerily deserted restaurant in Hampstead village. He was already there when I arrived, seated foursquare at a small table with his back to the wall and his eyes on the door. Inevitably it occurred to me to wonder how many empty restaurants, bars and cafes he had sat in like this, waiting and watching, in the days when he was a spy. He always played down the significance of those days, speaking of them with wry amusement, and giving the impression that in the world of espionage he had been little more than a pen-pusher. I chose to believe him.

That Hampstead meeting wasn’t our last – later he came to Dublin and Cork to investigate his father’s Irish roots, since he was thinking of giving up on Brexitland for Ireland – but it’s the one I recall most vividly. He was 88, yet he had the vigour and alertness of a far younger man. When I heard the news of his death, immediately a picture came to me of him striding along in the rain that day, in his George Smiley overcoat, his great square handsome head cleaving the air like the stem of a battle cruiser. He was a big man, in so many ways.

His biographer Adam Sisman quoted him saying that “people who have had unhappy childhoods are pretty good at inventing themselves”. In conversation, he returned again and again to his own childhood, which he looked back on with a kind of wonderment, amazed at the fact of having survived it; survived, and thrived. His father, Ronnie, had been a conman and chancer on an epic scale – a person representing a London hospital turned up at his funeral to fetch his head, claiming Ronnie had long ago sold it to the hospital for research purposes – and his mother abandoned him and his brother when they were schoolboys, never to return.

Was he his own invention? Well, aren’t we all? He seemed to me thoroughly authentic, the real thing, a man who fitted exactly the space the world allotted him. He was an old-fashioned patriot, with none of the bombast that might imply. He loved his country, but was disgusted by the upsurge of Little Englandism that followed the Brexit referendum. He was serious in the thought of moving to Ireland, but had he settled here, he would have been horribly homesick.

As a writer he transcended mere genre, showing that works of art could be made out of the tired trappings of the espionage novel – The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is one of the finest works of fiction of the 20th century. Along with Iris Murdoch, he sustained, and strengthened, the tradition of the mainstream English novel of manners; as a deviser of plots and a teller of stories, he was at the same level of greatness as Robert Louis Stevenson. His books will live as long as people continue to read. Samuel Beckett, asked to name what he considered to be his friend James Joyce’s greatest quality answered: “Probity.” Many of us would say the same of John le Carré, and doubly so of David Cornwell.

Tom Stoppard, playwright

He was David to his friends, and, enormous though that company was, one couldn’t help taking pride in belonging to it. The rewards were several. His handwriting on an envelope gazumped all other business, and to be at his table was an entertainment, an education and a catch-up on the news behind the news. As a storyteller, he did the police in different voices. And then there were the books; the prose, the perfect epithets, the throwaway gems. We all delighted in Smiley fumbling at his shirt front to polish his glasses with the end of his tie, forgetting that he was in evening dress. It’s so many years since I read it but I still remember the little shock of pleasure I felt.

He was Le Carré to me until we became friends over the film of The Russia House 30 years ago, one of the books that best showed off the alloy of radical anger and high romanticism that went into the building of the precision instrument that is a Le Carré novel in its prime. Recently he told me he had found his way to his next book. There was an obvious joy and also relief in his voice. Maybe that one is lost now, but the blow of losing David is immense and personal.

Charlotte Philby, author

My father’s hardback copy of The Little Drummer Girl stood for all of my childhood as the only novel on a shelf in our living room, otherwise reserved for more “serious” books. (Namely a dozen or so volumes of the OED.) As such, it took me a while to read it, once I found myself clawing for clues about the life of my grandfather, the double agent Kim Philby, about whom Le Carré was publicly scathing. Years later, I can still smell the pages as I cracked it open, in my late teens, and found myself immersed, for the first time, in one of his quietly devastating worlds. Over the years, I pored over every one of his books, drinking in his extraordinary observations on the political and the personal, and how these intersect. I’m so grateful to him for stories that helped me to understand the world that my grandfather inhabited, in dark grey technicolour. As an author, I’m always inspired by his ability to combine forensic thinking, a deftly crafted plot and a clarity about what it is to be human and flawed – and I am wholly resigned to the fact that anything I write will never touch it.

Margaret Atwood, author

John le Carré was a towering writer whose books are a teeming Dickensian guide to the bleak Machiavellian underworld beneath the international power struggles of the last 70 years. Like so many, I was first gripped by The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, then captivated by the Smiley novels. Orwell, Greene, Le Carré – how essential they are, especially now, and how fatuous they render the division into “literary fiction” and “genre”. Thank you, dear John, from one of your highly admiring Constant Readers.

No comments:

Post a Comment