|

| Michelle de Kretser’s new book Scary Monsters is split down the middle: one half tells a realist tale of France in the early 1980s, the other conjures a gruesome vision of Australia’s near future. |

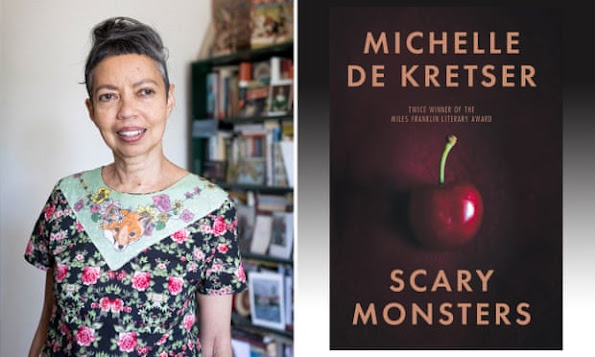

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser review – duelling novellas of charged, peerless writing

Mon 18 Oct 2021 17.30 BST

Michelle de Kretser’s fiction does more than beckon us in; it requires us to show up. The reward is room to wonder in both senses of the word. But her new novel demands tactile participation. Scary Monsters is split sharply down the middle. One half tells a realist tale of the early 1980s, the other conjures a gruesome – and plausible – vision of Australia’s near future. Either could function as the book’s opening act, and de Kretser places the choice in our dog-earing hands.

Scary Monsters is a two-headed creature: two stories, two front covers. In her seventh novel, the author turns the proverb into a dare: just try to judge this book by its cover. And how will you choose? Will you trust your eyes? Seek the linear comforts of chronology, or run the clock backwards like a capricious little god? Flip a coin and surrender to the odds? Even no decision at all – a blind grab – is its own kind of decision.

De Kretser’s previous novel, The Life to Come (2017) – the second of her books to win the Miles Franklin Award – was also told in discrete stories: a string of five jostling beads. Brilliantly aloof, that novel had an ordinal logic and recurring characters to lead us from tale to tale. In abandoning both – no order, no guides – Scary Monsters creates even more room for the connective energies of de Kretser’s readership. Those who adored the duelling novellas of Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry (2018) will revel in the interpretive possibilities.

There’s a whiff of gimmick about it, but also that rarest of high-literary delights: play. And knowing that we’re responsible for the shape this book takes makes us all the more attentive – alert to wormholes and echoes, and de Kretser’s briar wit. Is there a question lurking in the first story that the second might answer? Is it the same question that would emerge if they were reversed? We cannot truly know, for what we encounter in the first half of Scary Monsters will haunt the second. This novel reminds that memory is a kind of poltergeist – its own scary monster.

And so we begin with Lili (past) or Lyle (future): two immigrant Australians, both of Asian heritage. Lili is teaching English to high-schoolers in the south of France, waiting to hear if she has been accepted to postgraduate study at Oxford. She’s young and clever and “streaked with unfocused ambition”. It’s the closing months of 1980 and the French election looms, with the possibility of an era-defining progressive swerve. “In those days I believed the past could be left behind like a country,” she remembers.

Alone in her student rental, with its rationed heat, Lili yearns for some kind of kindred recognition, to be seen. She’s tired of living tentatively, cowed by that unspoken Australian pressure “to creep and pass unnoticed” – to be a model immigrant. When she meets the flamboyant, punkish Minna – a girl alive with subversive art projects and grand aesthetic theories – a friendship flares into life. But is it a bond of mutual affection, or just another costume in wealthy Minna’s moral wardrobe, a friendship she wears for show?

Lili’s tale promises nostalgia – dappled light and hopeful youth – but her memories are laced with menace. The European papers are full of blood-spattered tales of the Yorkshire Ripper, and Lili’s downstairs neighbour is creepily attentive. It’s a red world of lipstick stains, blood clots and ripe-swollen cherries; of horror-movie jitters. Lili watches as north African immigrants are rounded up and removed from the city centre – the precious le centre historique – while French schoolchildren proudly read about Camus’s L’Étranger killing an Arab, and treat it all as existential metaphor. “It was the beginning for me of thinking about why some people had history, and other people had lives,” Lili explains. Every page of her story feels charged, like an open circuit waiting for its switch; a lurking wallop. It’s magnificent, peerless writing.

Meanwhile, in a palpably near future, Lyle is an unassuming bureaucrat in a sinister government entity – The Department – eyes also fixed on the future (“don’t look back. That’s not the Australian way”). After the pandemic, our federation has become a police state, a realm of hyper-corporatised compliance. Islam is outlawed, and law and order policy relies on punitive repatriation (“one immigrant grandparent in four is enough”). Year-round bushfires fug the air, summer temperatures are in the high 50s, and the Great Barrier Reef is a blanched mausoleum. Yet it’s illegal to speak of what’s been lost, or to campaign against inequity. In this Australia, the only way forward is forgetting. (Has it ever truly been otherwise?)

In his “Colgate-white” kit home on the outskirts of Melbourne, nestled on Spumante Court and around the corner from Cold Duck Parade, Lyle craves the safety of middle-management anonymity. While Lili longs to be seen, Lyle strives for competent invisibility. But his wife, Chanel, is ambitious. What might the couple be willing to sacrifice in order to live in inconspicuous prosperity?

Layered over Lyle’s Orwellian terrors, de Kretser paints a burlesque – a comedy with a rictus face. She conjures a future where children are called Ikea and Prada, and commuters play Whack-a-Mullah on their phones, cattle prods at the ready to poke their way through the homeless hoards. There are some tired gags here – Gwyneth Paltrow’s vagina candle, and Justin Bieber tribute albums – and also some of the discomforting blitheness that satire often rouses. But the grotesqueries here are all of our own making.

To begin Scary Monsters, you must turn your unfavoured half of the book upside down. It’s a tidy, hardworking metaphor. “When my family emigrated, it felt as if we’d been stood on our heads,” Lily tells us. “Events and their meanings came at us from different angles.” And so de Kretser brings us a disorientating, angular novel. Lyle and Lili’s stories may read like counterweights, but the truest monster of this book is the possibility that there’s only one way to read it: our complacency and its terrifying punchline.

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser is out now through Allen & Unwin

No comments:

Post a Comment