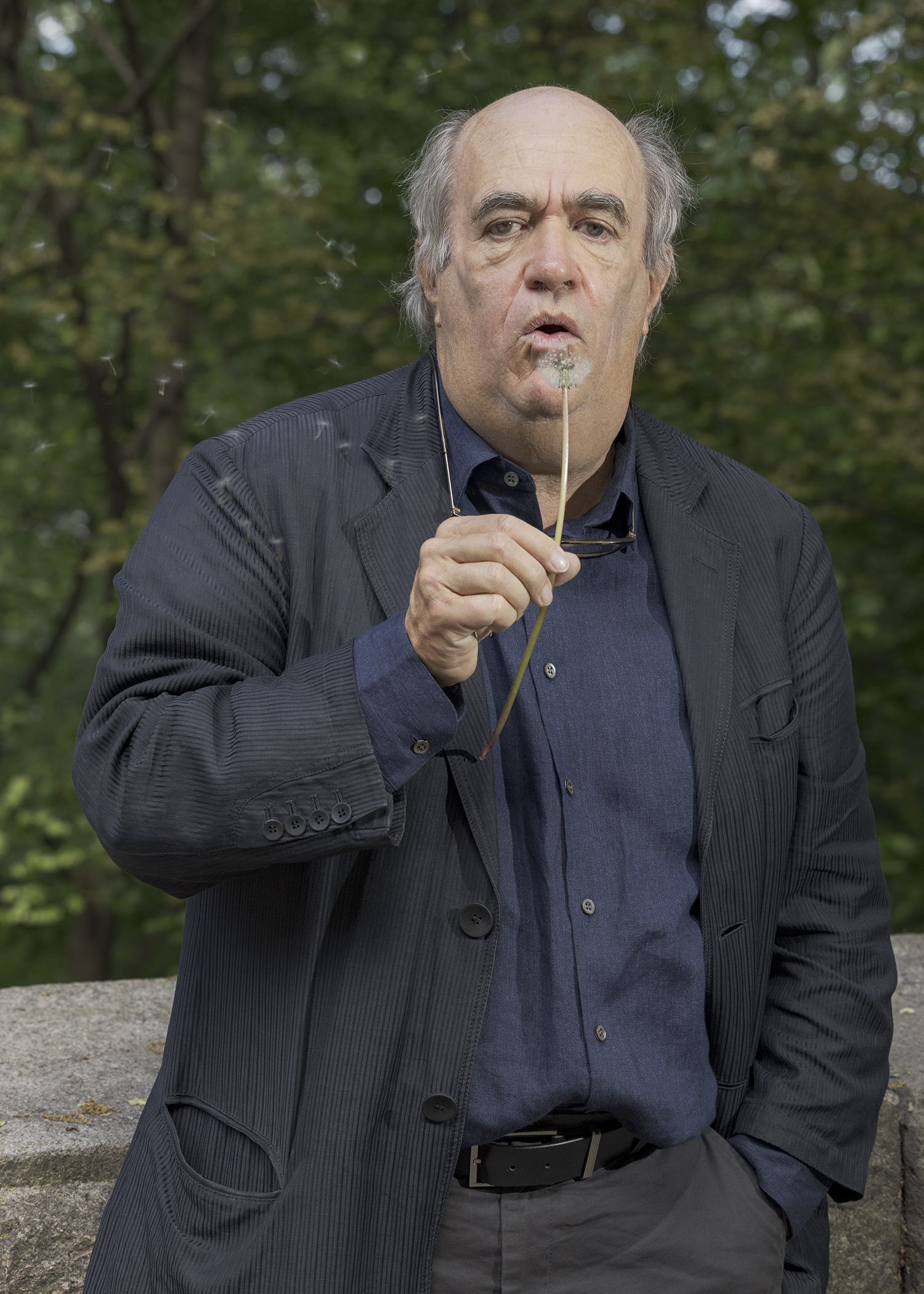

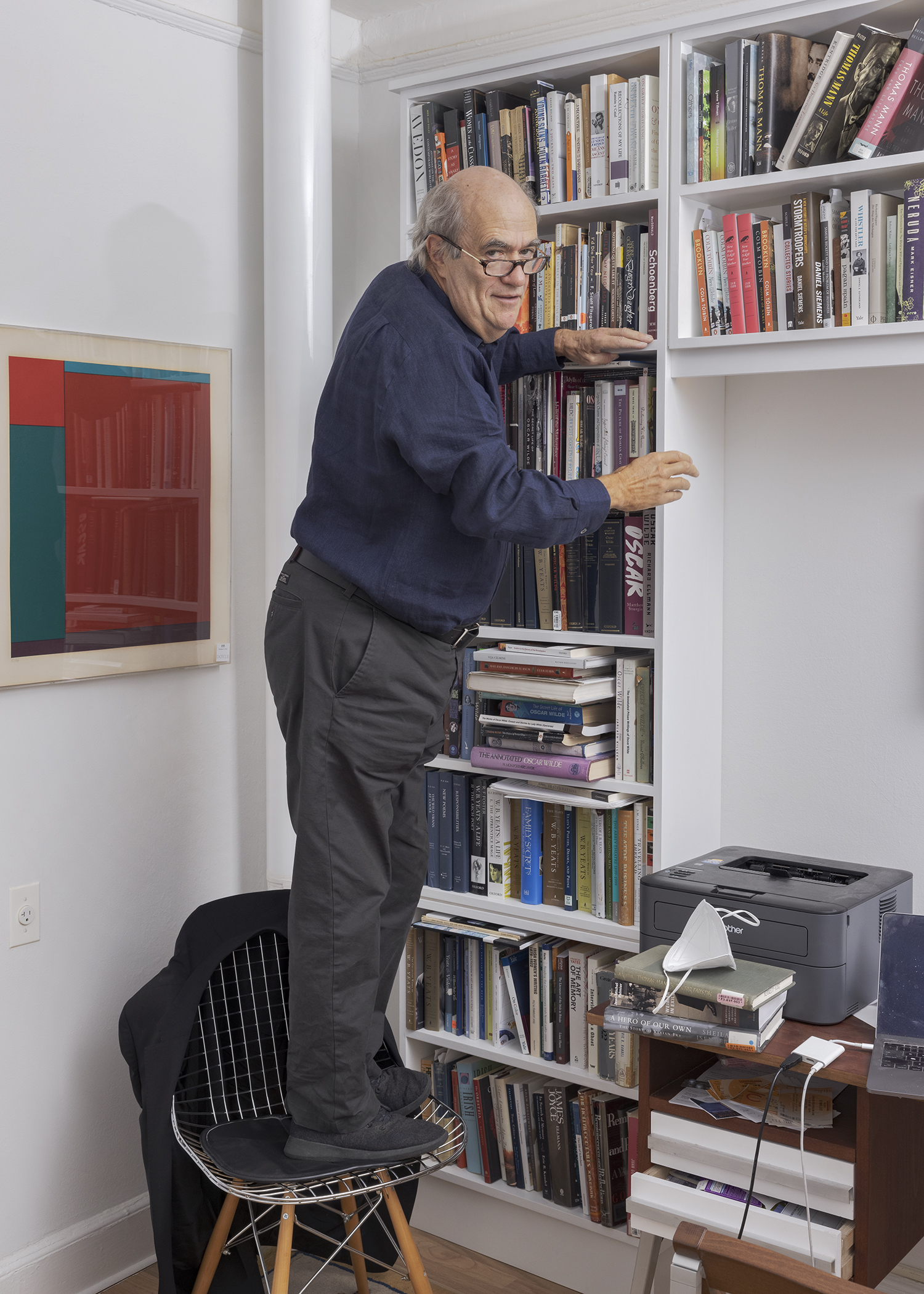

Colm Tóibín Knows What Moves the Heart

The moon, the Virgin Mary, the beauty of internal organs—these are just a few of the topics that come up when Irish author Colm Tóibín and American artist Kiki Smith get together. This time, the occasion is Tóibín’s tenth novel, The Magician, an imaginative, exquisitely researched account of the public and private life of the great German writer Thomas Mann. If every novel is a conversation between author and reader across time, Tóibín brings it full circle. He takes us back to Mann’s age, where we meet an ambitious, closeted artist at the turn of the 20th century, mixing in German aristocracy and bohemia, just as the world was turning “modern.” Here, from across the Atlantic, two friends talk about their creative impulses and how art gets made when you leave the ego out.

———

KIKI SMITH: My father’s side of the family is Irish. Five generations of Irish Americans until my father’s parents died and then they all just married any old body. But my father would always tell me that the Irish had the largest vocabulary of any agricultural people in the world. Was that just romance on his part?

COLM TÓIBÍN: You can put it down to oppression. If you have no symphony orchestra, if you have no galleries, then the oral becomes the performance.

SMITH: I often wonder if it’s all tied to the landscape, what’s available in terms of resources. Not all places are like Italy or Germany where you can drown in all the making of art.

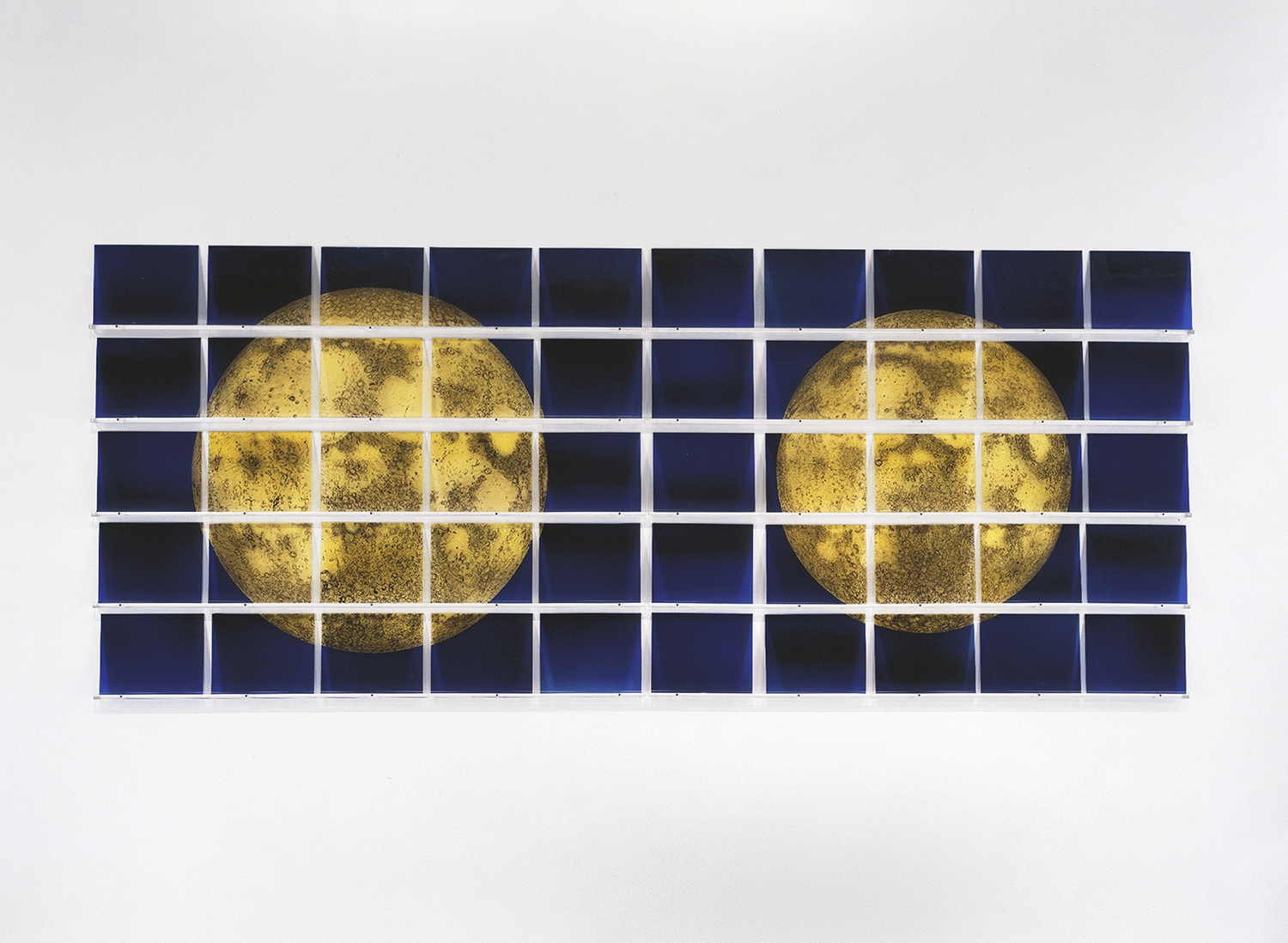

TÓIBÍN: I’ve been thinking of your work, and I have something I want to read to you. It’s the second stanza of a poem, “The Moon and the Yew Tree” by Sylvia Plath. “The moon is no door, it is a face in its own right. White as a knuckle, and terribly upset.” And then in the next stanza, she writes, “The moon is my mother. She’s not sweet like Mary. Her blue garments unloose small bats and owls.” I wanted to hear your thoughts about that.

SMITH: Beautiful. I think about pollinators a lot—nighttime pollinators as opposed to daytime pollinators. I’m making a little chapel for Mary, and for me, Mary has a fierce command like the kind you see in American nuns. A command to social justice and social responsibility. And she also has a hidden fierceness, like the moon does. Last night there was a full lunar eclipse. It was a big blood moon, but you could only really see it from the West Coast.

TÓIBÍN: You’ve done brilliant images of the moon. How do you make them?

SMITH: They came out of me when I was teaching. I would take students around Munich and they were completely bored with me dragging them all over, so I sent them to the planetarium. I found a book of the moon, and I started making 15-foot paintings in sections. I’ve made a lot of them, including glass paintings and prints of the moon. But they’re pretty straightforward. For this chapel, I’ve been thinking of adding a skylight, but then I thought I could make a painting of the moon instead, only a little less cold than I normally do it.

TÓIBÍN: For me, there’s an idea in your work of dealing with something directly. You’re not saying, this is a metaphor, or this is a piece of art. You’re saying, this is as near as I can get to touching the moon.

SMITH: I remember [Donald] Winnicott talked about artists wanting to expose themselves and remain hidden. Sometimes I think that things mean too much to me. But I really think an artwork is a collaboration between you and the universe, and you have your own secret part of it that means something to you. I’m not interested in other people knowing anything about me in a biographical sense. I just sit around and watch Netflix and scratch for ten hours a day. Most of my life is beyond boring. The challenge is to make something that somebody else can find some entrance in for themself to have an experience. What about you?

TÓIBÍN: In Ireland the song is more important than the singer. The singer’s job is to sing the song. So you never ever put yourself into the song, you put the song into the song. If you didn’t do that, as a singer, people would despise you.

SMITH: In reading you, I’ve always felt you have such a big space for kindness, for love, and for clarity. I used to make my work much cooler. And part of it was because I was afraid of language. I have this friend who’s a poet, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, who talks a lot about love, and about the things you care about. I realized how incredibly uncool it was in the art world to say you love or care about something. That might have had to do with feminism in the ’70s, how people didn’t want to be reduced to being the earth and the vessel and nature and all that. They said, “No, I want to go be an electrician’s assistant or do demo work.” But then I thought, no, that’s a really good alignment, to show what you care about and what you love. It always amazes me when people can just say things that are uncomfortable and stand in that discomfort.

TÓIBÍN: When I write about love, it’s always about loss. That other L-word is always there, wrapped around it in some way. I’m in Dublin now, and I’m only starting to write about this city because I’m away from it more than I’m here. So suddenly it’s appearing to me as history, as something lost, as something I can almost see. Whereas I can do that much easier with Enniscorthy, the town where I’m from, because I left that place long ago. I couldn’t dream of writing about New York, where I live now, but I can write about Spain, because I spent so much time there in my youth. These places are now becoming resonant for me, where I can make up fictional events happening in them. I love bringing back an old hotel in Dublin that’s no longer there and having someone sit in it. But tackling love is a complex business if you deal with it raw, because of sentimentality Pop music has taken so much of it from us. A lyric like, “I want you, baby.” You couldn’t write that in a poem or in a novel. You’d say, “Oh shut up, say something true. Say something interesting or raw.” But let me ask you something. You make work about the body. I wonder, can gay men get in on that?

SMITH: Everyone is in a body. Everybody knows the intolerable awkwardness of it. I just made things about bodies because I could hardly stand being in one. It’s not painful, it just felt so awkward. I had a friend who gave me a copy of Gray’s Anatomy and I opened it up and there were fat cells, and I thought, that’s me! I’m a fat cell. Then, nerve endings. That’s me! I’m a nervous wreck. It was like having a bible in front of you that you could find yourself in. My father [artist Tony Smith] would always talk to me about the muscles of the tongue. And he thought, between the tongue and the anus, the whole of life happens. Everybody is negotiating and navigating bodies in so many ways. You could look at any aspect of your body and see all of society and how people experience themselves—the shame of the body, the exhilaration and joyousness of the body, but also the economics of bodies, of whose bodies are cared for in this society and whose are discarded. The body has everything.

TÓIBÍN: I’ve been working on this novel about Thomas Mann, and one of his most famous books is The Magic Mountain. Similar to that book, his wife Katia was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1912 and went to a sanitarium in Davos, where he went to visit her. What Mann discovered there is the X-ray, and he puts it in his novel, because he’s going to be the first novelist to really deal with this idea of the ghostly inner self, the thing that no one can touch or feel. Another thing you’re reminding me of is that when I was in Austin, I started to go to a place called Barton Springs. It’s a famous swimming pool in the middle of Austin City. The lifeguard would go at about nine, but the place wouldn’t close until ten. So for the last hour it was ghostly and the water was barely lit. There’d be hardly anybody there. But one night in the dressing room, there were just two of us. The other guy was the most exquisite example of American white-boy–ness. He could not have been more perfect, more beautiful, more unconscious of himself. He just got naked like Americans do, and he started to walk around to shower. His showering was really theatrical. I started to think that no one could ever guess that inside him, all wrapped up in squelch, were livers and kidneys and spleen and lungs and guts. The oddest part was, he was so white, and so manicured, and so hairless and so utterly perfect. It was the most astonishing idea once you started to think about it.

SMITH: I know what you mean. I asked the artist David Wojnarowicz to come with me to a medical testing lab, and we made X-rays of us beating each other up. About ten years ago, I used an MRI to make a scan of my skull and printed it out, and it was that feeling of looking at something that I can never see. It is extraordinarily strange that we’re in a body.

TÓIBÍN: One of my closest relationships these days is with my oncologist, who I saw today. Everything is fine, but I have to see him every six months. The first time, he had to show me where the cancer was on a scan. And I said hold on, I can’t work it out. What perspective are we seeing my body from? It’s like holding carpaccio of yourself in your hands.

SMITH: The body is really a miracle. Also it’s a miracle that it’s the same body in most animals, just the pro- portions, the geometry, is changing and moving around.

TÓIBÍN: Then there’s the idea of Jesus on the cross, the idea of the arms outstretched and his body slumped, having some sort of primitive power to speak to the world to the point that he breaks down.

SMITH: It’s power. The Virgin Mary opens her arms, but not in the same way.

TÓIBÍN: I think Mary is much more interesting than Jesus. We literally know all of Jesus’s opinions, but we know Mary as silent. Her imploring is done with her arms. That we have to imagine a life for her makes her much more interesting, in my mind, than her son.

SMITH: Another thing that is really moving to me is the Deposition. The fallen Jesus. Last year I made a little sculpture of Jesus after seeing that exhibition at the Met that had Spanish baroque paintings from South America. There was a whipped, bloody Jesus with his limp body. It was not an active, erect body. He’s being held. Men are expendable. Historically, at least in art, they come to these violent ends more than women, their bodies are consumed. But for me, my sister died of AIDS in 1988, and it was very difficult on my mother. And I thought, that’s why people love the Virgin Mary. Her son has died. She means something to people who have lost loved ones, often too cruelly. But I was inspired by that limp pose of the figure. It’s like how a limp penis is always much more approachable to me.

TÓIBÍN: You’ve done a very beautiful drawing of a limp penis.

SMITH: In my father’s sculptures there was usually a mass and then an appendage. To me, the limbs are like that, you have this mass of the body that has a vitality and then you have these appendages hanging off it. The penis is sort of the most overt image of that, but arms are like that or hair falling. I think it’s an approachable pose in the representation of Jesus. Tell me, how important is it when you write that things remain hidden, or inexplicable or impenetrable or opaque?

TÓIBÍN: It’s absolutely essential. The tension is between concealment and revelation. And some of the concealment is when characters in fiction don’t know how they feel or don’t behave as they should. We all have an idea of the appropriate response to everything that occurs in the world, but we don’t actually respond that way. In fiction, it’s great if you have people at the moment, not doing, not feeling, not thinking. Simply stopping and thinking about something else, or whatever the mind does to avoid the experience. It’s not merely people deciding to pretend something didn’t happen, but to actually not experience it at all. So I think you do have relationships with the lost, with people in permanent states of concealment who are forced at a certain moment to say or feel something true. But it only comes after purgatorial levels of concealment of the self from the self. That’s the tension, the frozen self in the moment and then the ice cracking and something emerging that is a true feeling. That’s what I work with.

SMITH: I’m really like that. It’s not like I’m inaccessible to myself, but there are some things, like in most families, we never spoke about, and I don’t particularly have a language for it. I think it’s something to do with being Irish-American.

TÓIBÍN: We brought it to America. In America, two people meet and the first person talks all about themselves and what they’re feeling. And then the second person takes over and they do that, too. In Ireland that’s not how it happens. You tell jokes, you tell stories, you do imitations, but you don’t say what you’re feeling. It drives people in America nuts. But why would you want me to tell you how I’m feeling? Why would you want to know?

SMITH: I have this morbid melancholia that I attribute to my Irish-Americanness. I remember wanting to go to a funeral as a small child.

TÓIBÍN: In Ireland, from a very early age you get brought to funerals. When I was a kid, when some old lady or man died, you would be brought up to this person, who you’d only seen on the street, and there they would be laid out, dead, lying on their own bed in their bedroom. You could look up the nostrils. It was fascinating!

This November, Kiki Smith opens an art exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art in Zagreb, Croatia.

No comments:

Post a Comment