|

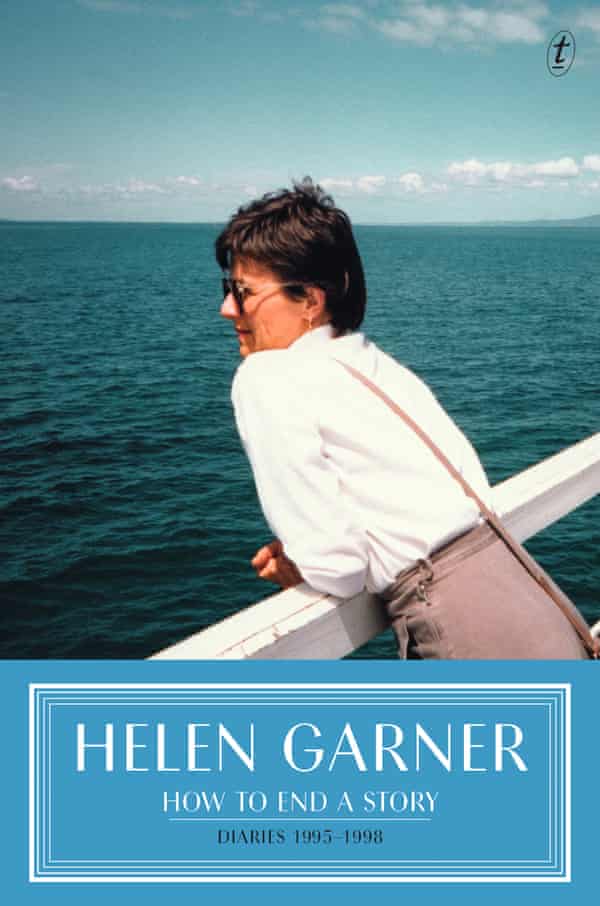

| Helen Garner: ‘During these hours of peculiar solitude, in conversation with myself and no one else,I’m free.’ Photograph: Darren James |

Helen Garner: I always liked my diary better than anything else I wrote

Garner has spent thousands of hours on her diary, writing every morning and night. It’s been useful for her other books – and it’s taught her she’s never alone

The 25 best Australian books of 2021

Wednesday 10 November 2021

When I was young, I liked writing. It was the only thing I was any good at, and I wanted to do it all the time. But I knew I would never be able to write a book.

A book, back then in the 50s and 60s, meant a novel. Novels were all I knew about. I’d read hundreds of them. But I thought you couldn’t write one unless you had an “idea” that you wanted to “express”. Writers, I learnt at school and university, had plots, and characters, and things called “themes”. I didn’t have any of those or know how to get them. All I had was a million details. I couldn’t see how it would ever be possible to make a container for the cascade of interesting stuff that poured past and through me each day.

But I liked pushing a pen, so I went on taking notes of the cascade as a way of keeping my head while it rushed on by, trying to capture bits of it in good sentences with grammar and punctuation, to get it into words in a way that relieved me. That’s how I started to keep a diary; and I’ve never stopped.

Eventually I got older and figured out how to pretend I was writing in the proper way. When I published my first “novel”, smart-arses saw through my charade and blew the whistle on me. “She’s only published her diary.” “She talks dirty and passes it off as realism.” This stung, but there was no point in caring. I was using the only material I had: the world as it presented itself to me, and through me. In other words, I was using myself.

Pretty much everything I’ve ever published was drawn from this compulsion to watch and witness and record. Great chunks of the diary turned out to be useful in the books I taught myself to write. I learnt to “invent characters” who could do and think things that people could interpret as “themes” if they wanted to. But it was all based on my driven, daily-and-nightly habit of writing things down. In my heart I always liked my diary better than anything else I wrote.

When I sit down to write something for publication, I’ll do anything to avoid the desk. I drag the chain for half a day at a time. I eat biscuits or put on the washing or vacuum the mats or lie on them and curse my fate. To write with conscious purpose I have to corral myself, to buckle on a harness before I can even start.

But every night before I go to sleep, and every morning when I open my eyes, I pick up my diary and my fountain pen, make a note of the date and time, and start writing. I never don’t want to. I never don’t feel like it or can’t be bothered. I just do it, sitting up in bed, and when I’ve been writing for 10 minutes or maybe an hour and feel like stopping, I stop – because I’m not writing for any reader other than myself. During these hours of peculiar solitude, in conversation with myself and no one else, I’m free.

I used to think (and often have been told) that there was something self-obsessed and neurotic about keeping a diary, that it was a way of defending myself from the world. Why would anyone be interested? Why on earth should a perfect stranger care, let alone feel something, when I describe, say, a dream I had of a bear in the back seat of a car? A broken umbrella in a bin, a rat in a kitchen, a bird that sings all night in a park? Isn’t it almost pathological, sitting there scribbling away by myself?

But I get letters from people. Strangers make lists of the things they recognise, and send them back to me. Sometimes they even say, “Thank you. This could be my life. This could be me.”

What I’ve learnt, from editing the diaries into books and putting them out there, is that during those thousands of private hours, I’m never alone. If I go far enough, if I keep going past the boring, obedient part of me with its foot always riding the brake, and through the narrow, murky parts that are abject or angry or frightened, I find myself moving out into another region, a bigger, broader place where everybody else lives: a fearless, open-hearted firmament where images swarm, and there’s music, and poetry that we almost understand, fleeting moments of sky and dirt, subtle changes in the light, a feather of a hesitation, mistakes and pain and getting over pain, all kinds of shouting and dawn and small nice things to eat, and being allowed to carry a stranger’s baby round a garden, and singing in the car all the way home.

No comments:

Post a Comment