Wednesday, March 31, 2021

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

The 100 best novels / No 100 / True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey (2000)

The 100 best novels

written in English

No 100

True History of Kelly Gang

by Peter Carey

(2000)

Peter Carey rounds off our list of literary milestones with a Booker prize-winning tour-de-force examining the life and times of Australia’s infamous antihero, Ned Kelly

Sunday 16 August 2015 09.00 BST

A note on the text

Three more from Peter Carey

021 Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871-2)

031 Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897)

036 The Golden Bowl by Henry James (1904)

040 Zuleika Dobson by Max Beerbohm (1915)

041 The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford (1915)

042 The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan (1915)

043 The Rainbow by DH Lawrence (1915)

044 Of Human Bondage by W Somerset Waugham (1915)

045 The Age of Innocence by Edith Warthon (1920)

046 Ulysses by James Joyce (1922)

047 Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis (1922)

048 A Pasage to India by EM Forster (1922)

049 Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loss ( 1925)

050 Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (1925)

051 The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

052 Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1926)

061 Murphy by Samuel Beckett ( 1938)

062 The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939)

063 Party Going by Henry Green (1939)

064 At Swim-Two-Birds by Flann O'Brien (1939)

065 The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (1939)

066 Joy in the Morning by PG Wodehouse (1946)

067 All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren (1946)

068 Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry (1947)

069 The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen (1948)

081 The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing (1962)

085 The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1966)

096 Breathing Lesson by Anne Tyler (1988)

097 Amongst Women by John McGahem (1990)

098 Underwold by Don DeLillo (1997)

099 Disgrace by JM Coetzee (1999)

Monday, March 29, 2021

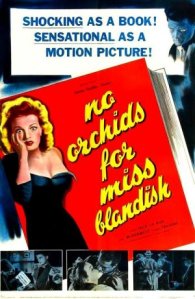

No Orchids for Miss Blandish by James Hadley Chase / Review

|

| James Hadley Chase |

NO ORCHIDS FOR MISS BLANDISH

(1939)

by James Hadley Chase

Cavershamrag1 April 2014

What can you say about this infamous crime story – that as a book and again as a film it was once the most notorious title in the UK? That it was critically lambasted by George Orwell? That it sold millions of copies and was adapted several times for television, stage and the cinema? That more people have heard of it than actually read it? What was the fuss all about? Well, this twisted beauty and the beast story starts with a roadside stick up in Kansas City …

What can you say about this infamous crime story – that as a book and again as a film it was once the most notorious title in the UK? That it was critically lambasted by George Orwell? That it sold millions of copies and was adapted several times for television, stage and the cinema? That more people have heard of it than actually read it? What was the fuss all about? Well, this twisted beauty and the beast story starts with a roadside stick up in Kansas City …

I submit this review for Katie’s 2014 Book to Movie Challenge at Doing Dewey; Bev’s 2014 Golden Age Vintage Mystery Challenge; and Todd Mason’s Tuesday’s Overlooked Film meme at Sweet Freedom.

“There was something so repulsive and terrifying about this creature that she had a mad urge to scream and keep on screaming”

George Orwell / Raffles and Miss Blandish

George Orwell

Raffles and Miss Blandish

James Hadley Chase / No Orchids for Miss Blandish

Sunday, March 28, 2021

Artists in Conversation / Cristina Peri Rossi by Carmen Boullosa

Spike Jonze / Her - review

Her – review | Mark Kermode

Sunday 16 February 2014 00.05 GMT

'My nerves are going fast' / The Grapes of Wrath’s hard road to publication

|

| John Steinbeck |

'My nerves are going fast': The Grapes of Wrath’s hard road to publication

Famously written in 100 days, John Steinbeck’s novel drew on years of other work and an agonised sense of duty to migrant farm workers

Sam JordisonTuesday 13 August 2019

In March 1938, shortly before he began working on The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck wrote to his agent Elizabeth Otis to turn down a commission to write about migrant workers.

“The suffering is too great for me to cash in on it … it is the most heartbreaking thing in the world,” he wrote. “I break myself every time I go out because the argument that one person’s effort can’t really do anything doesn’t seem to apply when you come on a bunch of starving children and you have a little money. I can’t rationalise it for myself anyway. So don’t get me a job for a slick.”

Saturday, March 27, 2021

Johnny Bear by John Steinbeck

Johnny Bear

by

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck / Johnny "El Oso"

The village of Loma is built, as its name implies, on a low round hill that rises like an island out of the flat mouth of the Salinas Valley in central California. To the north and east of the town a black tule swamp stretches for miles, but to the south the marsh has been drained. Rich vegetable land has been the result of the draining, land so black with wealth that the lettuce and cauliflowers grow to giants.