|

| James Hadley Chase |

NO ORCHIDS FOR MISS BLANDISH

(1939)

by James Hadley Chase

Cavershamrag1 April 2014

What can you say about this infamous crime story – that as a book and again as a film it was once the most notorious title in the UK? That it was critically lambasted by George Orwell? That it sold millions of copies and was adapted several times for television, stage and the cinema? That more people have heard of it than actually read it? What was the fuss all about? Well, this twisted beauty and the beast story starts with a roadside stick up in Kansas City …

What can you say about this infamous crime story – that as a book and again as a film it was once the most notorious title in the UK? That it was critically lambasted by George Orwell? That it sold millions of copies and was adapted several times for television, stage and the cinema? That more people have heard of it than actually read it? What was the fuss all about? Well, this twisted beauty and the beast story starts with a roadside stick up in Kansas City …

I submit this review for Katie’s 2014 Book to Movie Challenge at Doing Dewey; Bev’s 2014 Golden Age Vintage Mystery Challenge; and Todd Mason’s Tuesday’s Overlooked Film meme at Sweet Freedom.

“There was something so repulsive and terrifying about this creature that she had a mad urge to scream and keep on screaming”

Far and away the most famous single work by British writer René Brabazon Raymond (who published most of his nearly 100 books either as ‘James Hadley Chase’ or ‘Raymond Marshall’), Miss Blandish marked his fiction debut in 1939 and was met with genuine and uniform hostility from critics – but was lapped up by readers. Quite why it was disliked and seemed so shocking is now less easy to gauge, not just because we are less easily taken aback by depiction of violence today but because the standard edition that has been in circulation for the last 50 or so years is not the same one that Orwell read. The approved text in fact is derived from some limited changes first made in 1942 but mostly from more radical alterations Chase imposed for a 1961 paperback reprint. These substantially amended the story, changed the fate of some of the characters and toned down its depictions of sex and violence quite considerably.

“It’s women and money that make the world go round”

Some of the changes in the 1961 version are mere updates, like the substitution of TV for radio and removal of references to Clark Gable, but in other respects the book has been quite heavily re-written and with sections removed in their entirety so that overall it is much smoother in terms of prose but also somewhat shorter – and not necessarily better. While much less crude and obviously exploitative in some aspects, by removing much of the violence and perhaps more significantly the threat of violence (sexual and physical), combined with changes to the plot, this definitely makes the book much less intense, especially the crucial nature of the relationship between Miss Blandish and her psychotic kidnapper, Slim Grisson.

Some of the changes in the 1961 version are mere updates, like the substitution of TV for radio and removal of references to Clark Gable, but in other respects the book has been quite heavily re-written and with sections removed in their entirety so that overall it is much smoother in terms of prose but also somewhat shorter – and not necessarily better. While much less crude and obviously exploitative in some aspects, by removing much of the violence and perhaps more significantly the threat of violence (sexual and physical), combined with changes to the plot, this definitely makes the book much less intense, especially the crucial nature of the relationship between Miss Blandish and her psychotic kidnapper, Slim Grisson.

For example, to pick a not especially contentious section from the opening page, which in the later version is more specific about the geography (if you see a reference to Highway 54 in the second paragraph, you’re reading the later version), here is the description of the girl serving at a diner:

1939 version:

The blonde, who was leaning over the counter, gave him a smile that made Bailey think of a piano. She had worked on herself until she looked as good as any movie star until you got close to her, then she wasn’t so hot. She patted her tight little curls and stretched so that her large breasts poked at Bailey through her thin dress.

‘I bet you couldn’t sleep’, she said. ‘Aint this heat wicked? …’

Bailey scowled at her …

1961 version:

The blonde leaning over the counter smiled at him. She had big white teeth that reminded Bailey of piano keys. She was too fat to interest him. He didn’t return her smile.

The plot however remains basically the same: society girl Miss Blandish, out celebrating her birthday with the diamond necklace she was given by her millionaire father, is held up by Riley and a couple of buddies. When her boyfriend is killed in the ensuing scuffle, the gang get scared and spirit the girl to their hideout Unfortunately for her, the kidnappers are themselves wiped out by the Grisson Gang, run by Ma and her psychotic son Slim. And Slim, after seeing her, for the first time gets interested in women and decides to keep Miss Blandish to himself. The book then makes an interesting transition to 3 months later – everyone assumes Miss Blandish was killed as nothing happened after the ransom (half a mill in the original, double that in the rewrite) was paid. Her father hires Dave Fenner, an ex-reporter and now an inevitably impecunious private eye with a devoted secretary (natch), to find those responsible. Through Riley’s ex-girlfriend, Fenner discovers that the Grisson gang have bought a nightclub, investing the ransom money via a third party so as not to implicate themselves. It turn out that Slim had a special suite built into the back where he keeps Miss Blandish imprisoned. To make her comply, Ma Grissom regularly administers drugs. While this has been downplayed in the 1961 revision, we eventually realise that Miss Blandish has through the months of physical and psychological abuse – and with the sustained drug intake – become completely attached to Slim and, in a version of what we would now call the Stockholm Syndrome, is unable to leave. This was fairly unusual for its day and really does give the book’s beauty and the beast story an additional psychological kick. Speaking of kicks, yes, the 1939 version is pretty violent, no question about it, and this has been substantially reined in for the 1961 edition.

The plot however remains basically the same: society girl Miss Blandish, out celebrating her birthday with the diamond necklace she was given by her millionaire father, is held up by Riley and a couple of buddies. When her boyfriend is killed in the ensuing scuffle, the gang get scared and spirit the girl to their hideout Unfortunately for her, the kidnappers are themselves wiped out by the Grisson Gang, run by Ma and her psychotic son Slim. And Slim, after seeing her, for the first time gets interested in women and decides to keep Miss Blandish to himself. The book then makes an interesting transition to 3 months later – everyone assumes Miss Blandish was killed as nothing happened after the ransom (half a mill in the original, double that in the rewrite) was paid. Her father hires Dave Fenner, an ex-reporter and now an inevitably impecunious private eye with a devoted secretary (natch), to find those responsible. Through Riley’s ex-girlfriend, Fenner discovers that the Grisson gang have bought a nightclub, investing the ransom money via a third party so as not to implicate themselves. It turn out that Slim had a special suite built into the back where he keeps Miss Blandish imprisoned. To make her comply, Ma Grissom regularly administers drugs. While this has been downplayed in the 1961 revision, we eventually realise that Miss Blandish has through the months of physical and psychological abuse – and with the sustained drug intake – become completely attached to Slim and, in a version of what we would now call the Stockholm Syndrome, is unable to leave. This was fairly unusual for its day and really does give the book’s beauty and the beast story an additional psychological kick. Speaking of kicks, yes, the 1939 version is pretty violent, no question about it, and this has been substantially reined in for the 1961 edition.

“Can I hit him once more, Captain?” he asked hopefully, doubling his fists”

Even some modern sources have been absurdly, even hysterically, critical of the book but to me this still seems quite a well structured and thematically rich work – for instance, the fact that Miss Blandish has no first name points to her being somehow incomplete, as per the title, a theme explored in an original and unusual fashion, if somewhat murkily and probably with too much emphasis in the 1961 rewrite. Despite the sordid milieu, high body count and roughness of some the writing (and some very unconvincing use of American slang), the book is definitely worth a look or two. George Orwell famously took the novel apart in his 1944 essay ‘Raffles and Miss Blandish’ (which you can access online here) and it remains a fascinating analysis that does not in fact play down Chase’s skills – the argument is purely ideological.

“it is not, as one might expect, the product of an illiterate hack, but a brilliant piece of writing, with hardly a wasted word or a jarring note anywhere” – George Orwell

Orwell rightly pointed out the book’s large debt to Faulkner’s 1931 book Sanctuary, a book written as a money-making ‘shocker’ that easily transcended its intended generic confines and which I’ll be reviewing here at Fedora soon-ish. Despite what you may feel about violence in fiction (I’m not keen), generally speaking the 1939 version is certainly preferable and thankfully is available as an e-book from the ‘Murder Room’ imprint and on  paper too (albeit rather expensively) from Brun Crimeworks in an edition that claims to offer both the original text and the revised versions too. For an especially detailed analysis of the book, its various possible inspirations and the bewildering changes made to the various editions over the decades, you really must check out John Kelly’s long and fascinating essay, Some Orchids for James Hadley Chase. A huge hit that led to Chase’s belated follow-up, The Flesh of the Orchid (1948), the author also co-adapted the book into a stage play and then went on to see it turned into several films. The book’s popular success, and its subject matter, inevitably made it ripe for adaptation into other media – here’s a quick rundown of some of the highlights:

paper too (albeit rather expensively) from Brun Crimeworks in an edition that claims to offer both the original text and the revised versions too. For an especially detailed analysis of the book, its various possible inspirations and the bewildering changes made to the various editions over the decades, you really must check out John Kelly’s long and fascinating essay, Some Orchids for James Hadley Chase. A huge hit that led to Chase’s belated follow-up, The Flesh of the Orchid (1948), the author also co-adapted the book into a stage play and then went on to see it turned into several films. The book’s popular success, and its subject matter, inevitably made it ripe for adaptation into other media – here’s a quick rundown of some of the highlights:

- 1942 – stage adaptation by Chase and Robert Nesbitt. It starred Robert Newton as Slim and Linden Travers as Miss Blandish, a role she later recreated in the 1948 film version

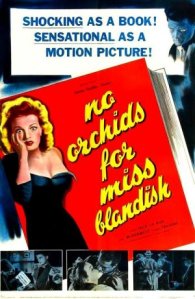

- 1948 – British film adaptation (see below)

- 1971 – filmed again as The Grissom Gang by hardboiled auteur Robert Aldrich

- 1978 – French TV version, Pas d’orchidées pour Miss Blandisch , starring Robert Hossein as Slim and Sophie Deschamps as ‘Miss Blandisch’.

- 2011 – audiobook version read by Jeff Harding

Released in 1948, the highly peculiar film adaptation by St. John Legh Clowes has mostly British actors put on unconvincing American accents, though at least Slim is played by US actor Jack La Rue, who not coincidentally had played the equivalent role in The Story of Temple Drake, Paramount’s 1933 adaptation of Faulkner’s Sanctuary. It makes for fascinating viewing as it tightens up and simplifies the plot and inevitably tones down the violence. It also, perversely but inevitably, softens the relationship between Slip and Miss Blandish, turning them into a very weird romantic couple to assuage the censors. But in fact this does not really change the book as much as it sounds as there is more than a suggestion in the book that Slim, no matter how horribly, is somehow filling a gap in Miss Blandish’s life and indeed offers her a way out. This is of course a pretty troubling way to look at a story of a kidnapping (and implicitly rape) and it may explain some of the critical opprobrium that was heaped on both the book and film.

Banned in several areas of the UK, the film was still a box office success that made into that year’s top 10. However, it was met with utter dismay by British critical establishment of the time, though they seem to have largely objected to the mere fact that a British film was trying to pass itself off as American (as opposed to the hundreds of examples from the time when Hollywood made films with very hokey depictions of Britain). Here are a few choice samples of what the critics had to say in 1948:

“a piece of nauseating muck” – Sunday Pictorial

“a most sickening display of sadism, brutality and suggestiveness” – Evening Standard

“About as fragrant as a cesspool”– Daily Mirror

“A wicked disgrace to the British film industry” – Daily Express

“One of the most undesirable pictures ever turned out by a British studio” – The Daily Star

“The most sickening exhibition of brutality, perversion, sex and sadism ever to be shown on a cinema screen” – Monthly Film Bulletin

To read more about the film version, see what John Greco has to say over at Twenty Four Frames and Glenn Erickson’s fine analysis as his DVD Savant as well David Kalat’s typically thorough overview for TCM.

DVD Availability: The film is currently available both in the UK in the PAL format in an OK transfer and in the US in a far superior NTSC special edition that includes over an hour of new interviews with Richard Gordon (who oversaw distribution of the film in the US) and actor Richard Nielson. A Blu-ray edition is due out shortly from Indicator and promises to be something very special.

No Orchids for Miss Blandish (1948)

Director: St. John Legh Clowes

Producer: St. John Legh Clowes

Screenplay: St. John Legh Clowes

Cinematography: Gerald Gibbs

Art Direction: Harry Moore

Music: George Melachrino

Cast: Jack La Rue (Slim Grissom), Linden Travers (Miss Blandish), Hugh McDermott (Dave Fenner), Lilli Molnar (Ma Grissom), Walter Crisham (Eddie Schultz), Richard Nielson (Riley)

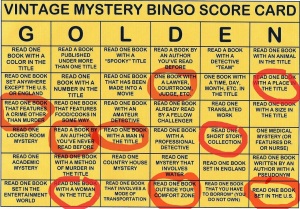

I submit this review for Bev’s 2014 Golden Age Vintage Mystery Challenge bingo in the ‘Woman in the title’ category:

No comments:

Post a Comment