|

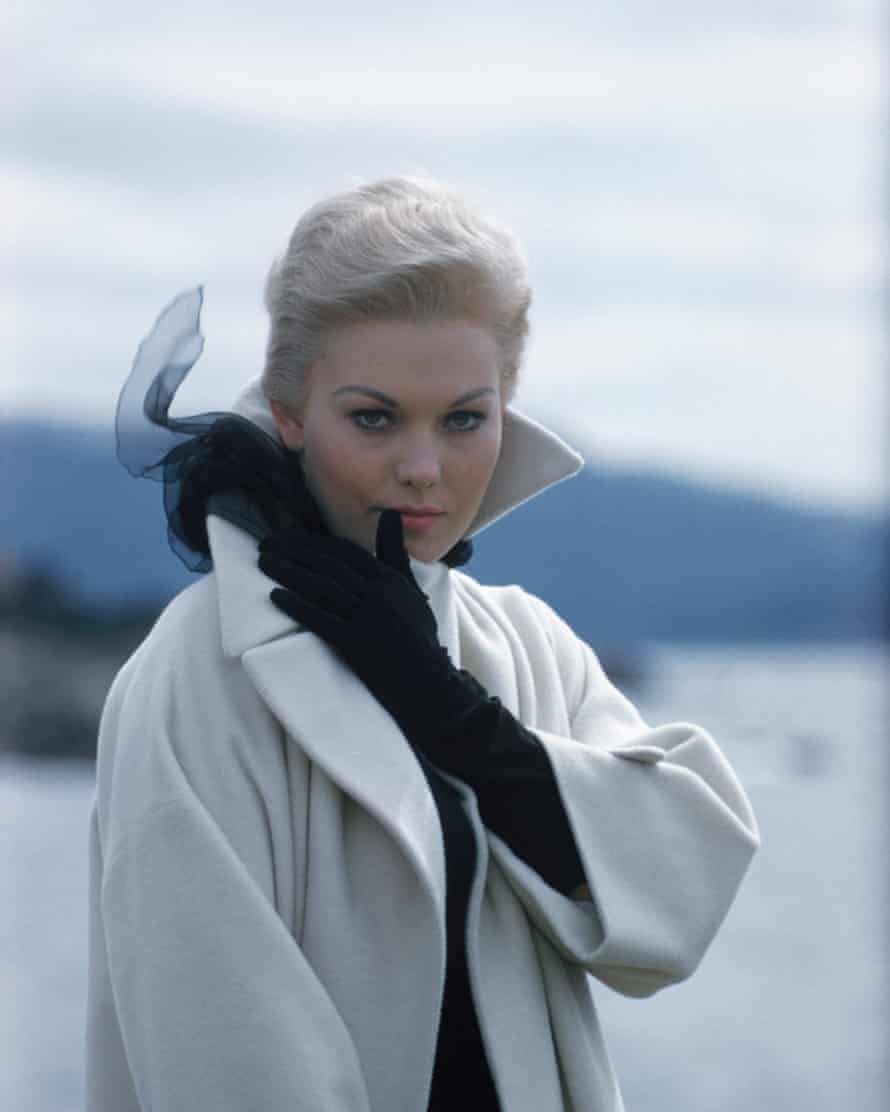

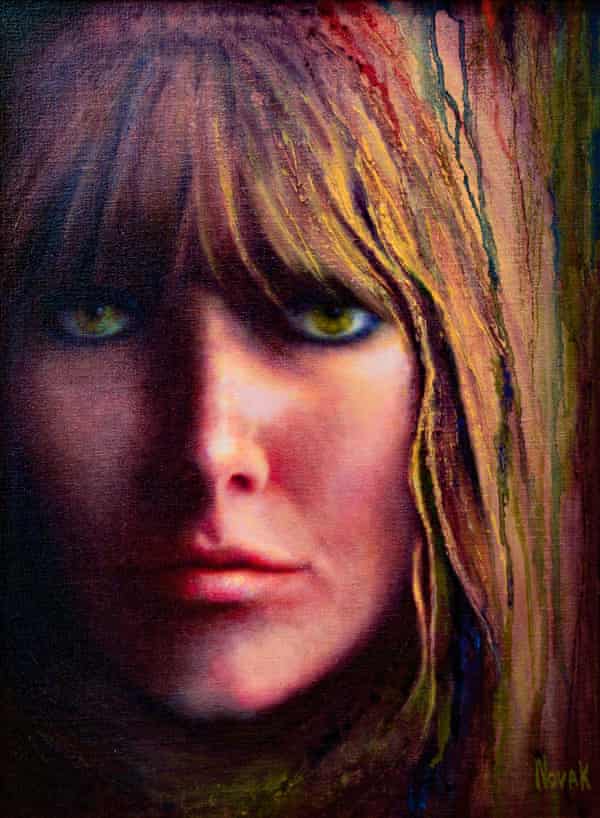

| Kim Novak |

‘I had to leave Hollywood to save myself’: Kim Novak on art, bipolar, Hitchcock and happiness

Simon HattenstoneKim Novak starred in Vertigo – voted the best film ever made – but knew she was too fragile for fame. She talks about her tough childhood, the sensitive side of Sinatra and starting again in her forties

Simon Hattenstone

K

im Novak apologises for the mess. And, to be fair, the studio at her Oregon home is fabulously messy. Behind her are a couple of canvases she has been working on; to the left and right, all sorts of all sorts. At the back of the room, her rescue dog, Patches, lies on a sofa, half snoozing, half listening. Occasionally, Sadie Ann, her husband’s pudelpointer, wanders in, sniffs around and leaves.

Novak, who turned 88 two days ago, is so much more than a Hollywood legend. The star of Hitchcock’s Vertigo is a wonderful artist, a mental health activist (she is proudly bipolar), an anti-bullying campaigner, a vet’s assistant and one of the greatest life forces I’ve spoken to.

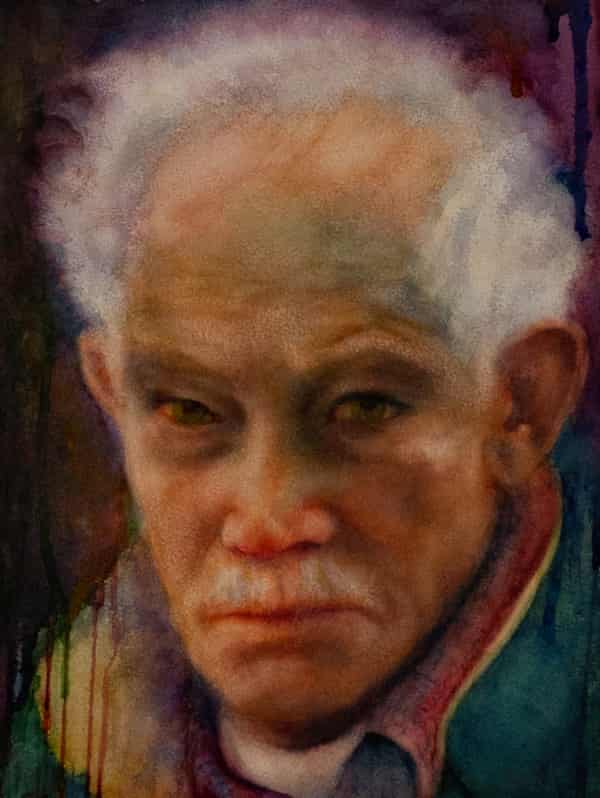

It is fewer than three months since Bob Malloy, her second husband, died. And here she is getting on with stuff, painting her way out of the blues, as she has done so often before. Novak turned down £1m for her autobiography decades ago, but now she is publishing a beautiful book of her art, dedicated to Malloy, accompanied by a few words that nod to rather than scrutinise the big events in her life. There are tender portraits of her parents and the many animals she has helped and harboured (Malloy was an equine vet), swirling surrealist landscapes in which creatures merge with the skies, and anthropomorphised trees dancing branch to branch.

“Painting’s always been there to rescue me. Since Bob passed, I’ve done his portrait so I could communicate with him,” she says. Novak sounds as husky as ever. They used to say it was a voice fashioned by whisky and fags. She says that is nonsense. “I never smoked cigarettes. Awful stuff – they don’t make you feel good. And I was never a drinker. I smoked grass; I still do. It’s relaxing. I like stuff that gives me images in my head.”

Novak was 21 when she played her first credited Hollywood role in the 1954 film noir Pushover, opposite Fred McMurray, who was a quarter of a century older than her. She says she made a terrible faux pas on set and bursts out laughing. “He had a trenchcoat on and he opened it up and, without thinking, I said: ‘Oh my God, that coat was made the year I was born!’ I thought: how stupid was that? But I never saw people as their age; I saw them as they were.” A year later, she starred in the Oscar-winning Picnic as Madge, a young girl who falls in love with William Holden’s older unemployed drifter.

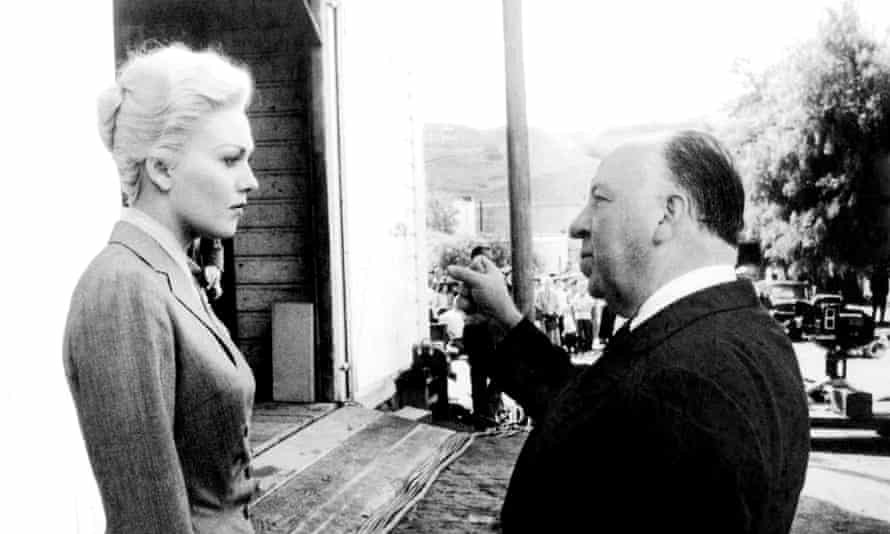

Then, at 25, came the twin roles in Vertigo that defined her Hollywood career – icy femme fatale Madeleine and shop assistant Judy. James Stewart’s retired detective, Scottie, falls in love with Madeleine, then tries to turn Judy into her. Ultimately, it transpires that Scottie is in love with an illusion, a woman who doesn’t exist.

It is a theme that resonates with her – men who want the impossible and try to reshape women into that dream. Even Malloy was a little like that, she says. “It happens in every marriage. My husband, whom I adored, wanted me to be more like how he wanted me to be. But I have too much of an independent personality. I’d be off painting and he wanted me to be more of a housewife.” And, she says, movie moguls are just the same. “In Hollywood, they think they want you, but really they want what they want you to be.”

Vertigo was dismissed as corny hack work when it was released in 1958. Last year, the British Film Institute voted it the greatest film ever. On set, Novak told Hitchcock there were bits she could make no sense of. “I said: ‘I can’t understand why you see Madeleine in the hotel window and then she disappears. How does she leave the hotel?’ And he said: ‘Ah, my dear, everything doesn’t have to make sense in a mystery.’”

How does she feel about it being ranked No 1 now? “It is amazing. And my critics are much kinder to me than they used to be. I think I was ahead of my time. All that acting stuff is so phoney now, when you look at it.”

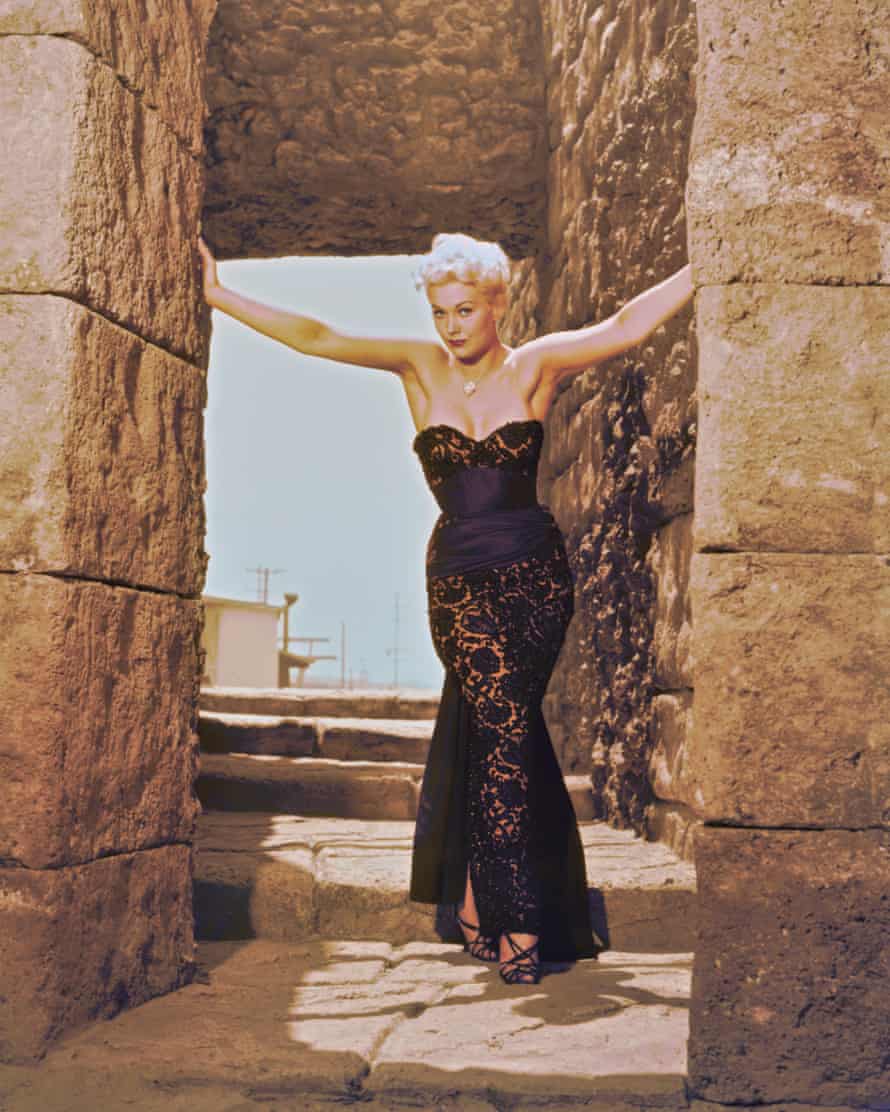

Novak says she didn’t know how to act, so she just reacted. Because she was starring in melodramas where large performances were expected, if not demanded, the critics often slated her. In films such as Pal Joey (where she plays showgirl Linda English opposite Frank Sinatra) or Kiss Me, Stupid (as hooker-with-a-heart Polly the Pistol alongside Dean Martin), there is a disconnect between the overall brash tone and her quiet stillness. She brings a surprising empathy and vulnerability to so many characters. And vulnerability is a theme she returns to time and again as we Zoom.

Novak was born Marilyn Pauline Novak in Chicago to severe, serious-minded Czech parents. Her father had been a history teacher, but became a dispatcher for the railroad in the depression, while her mother worked at a bra and girdle factory to make ends meet. Young Novak was so shy that she hid behind curtains when the family had visitors. They lived in a rough area of the city – a rape and murder hotspot. Her mother kept her in pigtails throughout her childhood and wouldn’t let her wear makeup, to ensure she didn,t attract the wrong sort – or any sort.

Her father wanted nothing more than for her to be a good student, while she wanted nothing more than to look out of the window and dream. The Catholic family lived in an almost exclusively Jewish neighbourhood and the local children would pick on her. “I often got knocked down, buried in snow and pied with mouldy deli pies.” That’s awful, I say. No, she says, it wasn’t – just think what those kids had just been through. “These were young innocent Jewish kids trying to seek revenge for the murders of their kin. And it didn’t help to have a grandpa whose first name was Adolf.” The way she says it is funny. But she is being serious. “To their minds, he could have been the man next door.”

Novak has said she was raped as a child, but has never gone into details. Does she think her mental health problems are related to that? “I inherited my mental illness from my father, but the rape must have added to it,” she says. I ask how old she was and whether the rapist was known to her. “It was in my early teens by multiple boys in the back seat of a stranger’s car.” She never told her parents about being bullied by other children, let alone the rape.

Novak won two scholarships to study fine art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her mother signed her up to a youth group called the Fair Teen Club, to help her get over her shyness, and the head of the club urged her to model. She won a beauty contest and became Miss Snow Queen. In the summer of 1953, she toured the US with three other girls demonstrating Thor refrigerators (they opened the fridge doors and sang: “There’s no business like Thor business”) and was crowned Miss Deep Freeze. On a visit to RKO Studios, she was invited to be an extra in two movies and was signed up by Columbia films, run by Harry Cohn.

Hitchcock had a reputation for mentally torturing his female stars, but Novak says he was fine with her. It was Cohn who was the monster. He asked her to change her name to Kit Marlow to make her more marketable. She refused, but compromised with Kim. Is it true he called her a dumb, fat Polack? “That’s right,” she says. “I wouldn’t have minded if I was, but I wasn’t a Polack. I was from Czechoslovakia. I’d be waiting for a meeting with him and he’d say: ‘Send the dumb Polack in, send in the fat Polack.” But you weren’t fat? “He just wanted to get a rise out of me.”

When rumours circulated that Novak was seeing Sammy Davis Jr, Cohn decided it would be bad for business if she had a relationship with a black man. “They refused to let me go near Sammy’s house. And I loved his family – they were so wonderful. Sammy had already lost one eye in an accident and Harry Cohn threatened to take out the other one. I’m sure he would have got his gangster friends to do it. Cohn was definitely in with the mob.”

And did she have a love affair with Davis? It is complicated, she says – she loved him, but wasn’t in love with him. Was he in love with her? “Yes, and I didn’t want to hurt him. He was a big child.” For Novak, that is a supreme compliment. “He always stayed so vulnerable, and you want to tread lightly on someone that vulnerable.”

She also adored Stewart, with whom she appeared in Bell, Book and Candle as well as Vertigo. “He lived in the midst of all that vanity and was never tainted by it,” she says. Was that unusual for a leading man? “Oh yeah, most leading men enjoyed the glamour of it all. So many times we would sit after the scene was over and we’d take off our shoes and put our feet up on the table and not even talk. We’d just hang out, because we were both real. It was hard for me to believe that somebody could live in Hollywood for so long, right in the middle of Beverly Hills, and stay real. He deserves a big trophy just for that; one that says: ‘I was real.’” She smiles. “I’d like that same trophy.”

Novak was also close to Sinatra, with whom she starred in two fine films – Pal Joey and The Man With the Golden Arm. “Frank Sinatra and I had a nice, friendly relationship at times.” Is that a euphemism? “It was a bit more than that. I had a relationship with Frank, yeah. He was a very sexy guy.”

Was Sinatra difficult? “He could be. If I’d only worked with him on the first movie, The Man With the Golden Arm, I’d be bragging about how wonderful he was. He could be kind and gentle – and he could be cocky, not wanting to listen to anybody but himself.”

In The Man With the Golden Arm, he plays a vulnerable heroin addict, while in Pal Joey he is a shyster love rat. Which side was truer to him? “The real Sinatra was a very sensitive person. But he was affected by people putting him on a pedestal, so he let that simple, beautiful side of him go. You can get lured into loving yourself too much. That’s why I left Hollywood. I didn’t want to get into all of that. I didn’t want to lose myself. I needed to leave to save myself. I like who I am, even with the suffering you go through, even with the fact that when you’re vulnerable you feel everything so intensely.”

Did she really think she might lose herself? “Absolutely. It’s exciting to dress up in gorgeous clothes and to feel sexy and to look sexy. It’s wonderful, but it’s a trap. You become satisfied with that being enough, then later in life it isn’t enough. So many people, once they got older and were no longer looked at for their beauty, just fell apart.”

One reason she never got carried away, she says, is because of her parents. She did everything for their approval and never got it. Her father saw her first two films, then refused to see any more. He hated the idea that she was a sex symbol. “He was afraid of seeing me in a light that he didn’t want to see me in.” Did that upset her? “Very much. Very much.” Did you ever talk to him about it? “I tried to. He was always talking about getting a little car. So I bought him that car and I said: ‘Daddy, we’re going to go across the country: I’m going to pick you up in Chicago and we’re going to drive out to LA.’ And all of a sudden he started getting this migraine.” They never went on the trip. “I had wanted to have this whole time for him to get to know who I was. He didn’t like the car.” Did he accept it as a present? “No. They sold it.”

Her Hollywood career was pretty much done and dusted within a decade. By 1966, after a marriage that lasted less than a year – to the English actor Richard Johnson, whom she had met on the set of The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders – she had had enough of the movies. She had struggled with depression since her teens and she feared for herself. “When you’re happy, you’re on a cloud higher than anybody can see. All of a sudden, the cloud turns grey and it starts putting pressure on you and before you know it you’re down at the bottom of the hole again.”

And she was disappointed by the work she was being offered. Cohn had died in 1958 and by the 60s she was largely being offered parts as a scantily clad beach babe. She wasn’t interested. “I wanted to be appreciated for what I was as a person and what I had to offer. I didn’t feel my work meant anything there. I knew I was a good artist and I wanted to express my feelings. Not the writer’s or the director’s; I wanted to express me. I wanted to play the role of somebody who was mentally ill. I think I could have done a really good job, because I knew those feelings.”

There were other signs that she should get out. She was living on the coast at Big Sur and she lost most of her valuables in a fire. She stayed put, but next came the mudslide that took away her home. She knew it was time to pack up and move on. “So I rented this van and took what was important to me. I took photographs, I took art stuff, and I thought: ‘That’s what’s important.’ The mudslide was telling me: ‘Your time is up; take off while you can. Get ahead of the game. Don’t wait till you’re too old and wrinkled. Then nobody will want you any more.’”

She ended up on the Pacific coast of Oregon, met Malloy, married him in 1976 and made a new life for herself. The focus now was assisting him with his work (“I loved helping him with surgeries – ‘Hold this eyeball while I try to put it back in its head.’ I felt useful”), art, poetry, riding horses, enjoying nature. She didn’t miss acting in the slightest. Occasionally, she returned to TV or film, only to find it reminded her why she had left. She says that, apart from Malloy, her relationships with animals have been the most important in her life. “I’m sure it’s my mothering instinct; since I’ve never had children, the animals are my children.” Did she want children? “No. To tell you the truth, I was always afraid that they’d have mental issues as well and I didn’t want them to suffer.”

In the early 00s, Novak was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Since then, she has spent time trying to normalise it, telling people it is just another illness that can be treated (in her case with antipsychotics) and not one to be stigmatised. She says she didn’t like lithium, another medication, because it made her put on weight. “I don’t want anything that makes me put on a lot of weight. I don’t feel good. My horse doesn’t appreciate it!” How much does she weigh? “You’re asking a lot of intimate questions! Some things should remain a mystery!”

Novak says that her art has had a positive effect on her bipolar and vice versa. “All those rages and feelings of depression, they leave you when you let them out. And that’s what painting is all about.”

She looks in great nick today – blond bob, purple hoodie, huge yellow-green eyes. But in 2014 her appearance was ridiculed by Donald Trump, who tweeted: “Kim should sue her plastic surgeon!” after she made a rare public appearance to present an award at the Oscars. To be fair, Novak is the first to admit she looked awful that night. “You know when you get insecure and you think somebody can help you? I didn’t want a facelift or anything like that, so I went to a doctor and he put some fat injections in my face. That was the stupidest thing I could have done. First of all, I didn’t need it, because I think my face is too round anyway. But it filled out my cheeks so I looked different.”

That wasn’t the only daft thing she did that night, she says. “I took a Valium on an empty stomach, because I was trying to starve myself to lose a couple of pounds. I was just like arhhhhhhhhhh – I had no energy.” Again, she says, it reminded her she wasn’t made for Hollywood. “I thought: ‘I’m much too vulnerable for this town. I take things to heart too much.’”

A couple of weeks later, she returned to Hollywood to do an interview in front of a live audience. “I didn’t want them to think they had got the best of me and that what they had said was going to take me down, so I went and talked about bullies in the interview.” Since then, she has campaigned against bullying. “There are kids who have taken their lives over what has been said about them. I felt I wanted to help be a role model.”

Novak says her 45 years with Malloy were the happiest of her life and that things have been tough since his death. “There were times I didn’t want to keep going without him. But now I light a fire every night and I fix something special – all the things he liked. He loved my chicken dumplings. I think: ‘Why didn’t I make that more for him?’” Painting, she says, has got her through the worst of it.

Friends worry that her home and four horses and two dogs are too much for her. And, yes, she may well give Malloy’s horse to his son, but she is going nowhere soon. “People say: ‘Are you going to stay in that house by yourself?’ I love this house. I designed this house. Of course I’m going to stay here. It’s right on the Rogue River. It’s just beautiful. I still ride my horse all the time. I hope I ride to the bitter end.” She pauses. “Not the bitter end; I hope I ride myself into heaven on my horse.” And she giggles like a little girl at the thought of it.

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment