|

| Kevin Wheatcroft’s collection of Hitler heads. He claims to have the largest collection in the world. Photograph: David Sillitoe for the Guardian |

The long read

The man who sleeps in Hitler’s bed

When he was five years old, Kevin Wheatcroft received an unusual birthday present from his parents: a bullet-pocked SS stormtrooper’s helmet, lightning bolts on the ear-flaps. He had requested it especially. The next year, at a car auction in Monte Carlo, he asked his multimillionaire father for a Mercedes: the G4 that Hitler rode into the Sudetenland in 1938. Tom Wheatcroft refused to buy it and his son cried all the way home.

When Wheatcroft was 15, he spent birthday money from his grandmother on three second world war Jeeps recovered from the Shetlands, which he restored himself and sold for a tidy profit. He invested the proceeds in four more vehicles, then a tank. After Wheatcroft left school at 16, he went to work for a Leicestershire engineering firm, and then for his father’s construction company. He spent his spare time touring wind-blasted battle sites in Europe and North Africa, searching for tank parts and recovering military vehicles that he would ship home to restore.

Wheatcroft is now 55, and according to the Sunday Times Rich List, worth £120m. He lives in Leicestershire, where he looks after the property portfolio of his late father and oversees the management of Donington Park Racetrack and motor museum (which he also owns). The ruling passion of his life, though, is what he calls the Wheatcroft Collection – widely regarded as the world’s largest accumulation of German military vehicles and Nazi memorabilia. The collection has largely been kept in private, under heavy guard, either in the warren of industrial buildings Wheatcroft owns near Market Harborough, or at his homes in Leicestershire, the Charente in south-west France and the Mosel Valley in south-west Germany. There is no official record of the value of Wheatcroft’s collection, but some estimates place it at over £100m.

Wheatcroft is a large, quiet man and a legend in the blokey, Clarksonish world of online military history obsessives. Among the internet tribes of second world war enthusiasts, the Wheatcroft Collection is spoken about in hushed, reverential tones – a near-mythical trove of military treasures. Now Wheatcroft, who has long been reluctant to publicise his vast archive of Nazi artefacts, is guardedly opening up his hoard to a wider audience, launching a rather creaky website and putting a handful of vehicles on display at his motor museum.

Since that initial stormtrooper’s helmet, Wheatcroft’s life has been shaped by his obsession for German military memorabilia. He has travelled the world tracking down items to add to his collection, flying into remote airfields, following up unlikely leads, throwing himself into hair-raising adventures in the pursuit of historic objets. He readily admits that his urge to accumulate has been monomaniacal, elbowing out the demands of friends and family. The French theorist Jean Baudrillard once noted that collecting mania is found most often in “pre-pubescent boys and males over the age of 40”; the things we hoard, he wrote, tend to reveal deeper truths.

Wheatcroft’s father, Tom, a building site worker from Castle Donington, came back from the second world war a hero. He also came back with a wife, Wheatcroft’s mother, Lenchen, whom he had first seen from the turret of a tank as he pulled into her village in the Harz mountains of Lower Saxony. He made hundreds of millions in the post-war building boom, then spent the rest of his life indulging his zeal for motor cars. He ran Donington Park racetrack and counted Ayrton Senna and Jean Manuel Fangio among his drinking buddies. He had his own race team – Wheatcroft Racing – and built up the world’s largest collection of racing cars.

In his autobiography, Thunder in the Park, Tom Wheatcroft comes across as a tricky character, a cut-throat haggler and difficult husband. During the 1970s, Lenchen moved out of the family home for eight years after a period when Tom, in the bantery brogue of his memoir, “had not been quite so single-minded as far as my own family life was concerned”. Lenchen took Kevin and two of his sisters to live in nearby Market Harborough. While there was, eventually, a reconciliation, Kevin spent the majority of his adolescence apart from his war-hero father. Tom supported his son in his early years of collecting; Wheatcroft speaks of his late father as “not just my dad, but also my best friend”. Tom died in 2009. Despite being one of seven children, Wheatcroft was the sole beneficiary of his father’s will. He no longer speaks to his siblings.

It is hard to say how much the echoes of atrocity that resonate from Nazi artefacts compel the enthusiasts who haggle for and hawk them. The trade in Third Reich antiquities is either banned or strictly regulated in Germany, France, Austria, Israel and Hungary. None of the major auction houses will handle Nazi memorabilia and eBay recently prohibited sales on its site. Still, the business flourishes, with burgeoning online sales and increasing interest from buyers in Russia, America and the Middle East; Wheatcroft’s biggest rival is a mysterious, unnamed Russian buyer.

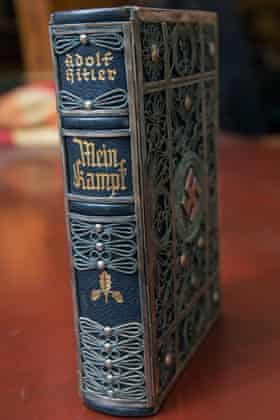

Naturally, exact figures are hard to come by, but the market’s annual global turnover is estimated to be in excess of £30m. One of the most-visited websites is run by Holocaust denier David Irving, who in 2009 sold Hitler’s walking stick (which had previously belonged to Friedrich Nietzsche) for $5,750. Irving has offered strands of Hitler’s hair for £130,000, and says he is currently verifying the authenticity of charred bones said to be those of Hitler and Eva Braun. There is also a roaring trade in the automobiles of the Third Reich – in 2009, one of Hitler’s Mercedes sold for almost £5m. A signed copy of Mein Kampf will set you back £20,000, while in 2011 an unnamed investor purchased Joseph Mengele’s South American journals for £300,000.

As the crimes of the Nazi regime retreat further into the past, there seems to be an increasing desperation in the race to get hold of mementos of the darkest chapter of the 20th century. In the market for Nazi memorabilia, two out of the three principal ideologies of the era – fascism and capitalism – collide, with the mere financial value of these objects used to justify their acquisition, the spiralling prices trapping collectors in a frantic race for the rare and the covetable. In Walden, Henry David Thoreau observed that “the things we own can own us too”; this is the sense I get with Wheatcroft – that he started off building a collection, but that very quickly the collection began building him.

When I went to Leicestershire near the end of last year to see the collection, a visibly tired Wheatcroft met me off the train at Market Harborough. “I want people to see this stuff,” he told me. “There’s no better way to understand history. But I’m only one man and there’s just so much of it.” We drove in his VW truck across flat countryside under a quivering winter sun. He was dressed in a fleece and hiking boots, a fine bushy head of hair streaming from beneath a flat cap, and had a shy, handsome face. Wheatcroft spoke to me in a rolling Midlands accent interrupted every so often by a yawn. He was knackered, he said. He had been trying to set his collection in order, cataloguing late into the night, and making frequent trips to Cornwall, where, at huge expense, he was restoring the only remaining Kriegsmarine S-Boat in existence. He felt he was being pulled in too many directions – there were the demands of his restoration projects, the racetrack at Donington Park, his property portfolio, and always, for the collector, a lead to be followed up, another gem to be uncovered.

Wheatcroft had recently purchased two more barns and a dozen shipping containers to house his collection. The complex of industrial buildings, stretching across several flat Leicestershire acres, seemed like a manifestation of his obsession – just as haphazard, as cluttered and as dark. As we made our way into the first of his warehouses, Wheatcroft stood back for a moment, as if shocked by the scale of what he had accumulated. Many of the tanks before us were little more than rusting husks, ravaged by the years they had spent abandoned in the deserts of North Africa or on the Russian steppes. They jostled each other in the warehouses, spewing out to sit in glum convoys around the complex’s courtyard. “Every object in the collection has a story,” Wheatcroft told me as we made our way under the turrets of tanks, stepping over V2 rockets and U-boat torpedoes. “The story of the war, then subsequent wars, and finally the story of the recovery and restoration. All that history is there in the machine today.”

We stood beside the muscular bulk of a Panzer IV tank, patched with rust and freckled with bullet holes, its tracks trailing barbed wire. Wheatcroft scratched at the palimpsest of paintwork to reveal layers of colour beneath: its current livery, the duck-egg blue of the Christian Phalangists from the Lebanese civil war, flaking away to the green of the Czech army who used the vehicles in the 1960s and 70s, and finally the original German taupe. The tank was abandoned in the Sinai desert until Wheatcroft arrived on one of his regular shopping trips to the region and shipped it home to Leicestershire.

Wheatcroft owns a fleet of 88 tanks – more than the Danish and Belgian armies combined. The majority of the tanks are German, and Wheatcroft recently acted as an adviser to David Ayer, the director of Fury (in which Brad Pitt played the commander of a German-based US Sherman tank in the final days of the war). “They still got a lot of things wrong,” he told me. “I was sitting in the cinema with my daughter saying, ‘That wouldn’t have happened’ and ‘That isn’t right.’ Good film, though.”

Around the tanks sat a number of strange hybrid vehicles with caterpillar tracks at the back, lorry wheels at the front. Wheatcroft explained to me that these were half-tracks, deliberately designed by the Nazis so as not to flout the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which stipulated that the Germans could not build tanks. Wheatcroft owns more of these than anyone else in the world, as well as having the largest collection of Kettenkrads, which are half-motorbike, half-tank, and were built to be dropped out of gliders. “They just look very cool,” he said with a grin.

Alongside the machines’ stories of wartime escapades and the sometimes dangerous lengths that Wheatcroft had gone to in order to secure them were the dazzling facts of their value. “The Panzer IV cost me $25,000. I’ve been offered two and a half million for it now. It’s the same with the half-tracks. They regularly go for over a million each. Even the Kettenkrads, which I’ve picked up for as little as £1,000, go for £150,000.” I tried to work out the total value of the machines around me, and gave up somewhere north of £50m. Wheatcroft had made himself a fortune, almost without realising it. “Everyone just assumes that I’ve inherited a race track and I’m a spoilt rich kid who wants to indulge in these toys,” he told me, a defensive edge to his voice. “It’s not like that at all. My dad supported me, but only when I could prove that the collection would work financially. And as a collector, you never have any spare money lying around. Everything is tied up in the collection.”

Leaning against the wall of one of the warehouses, I spotted a dark wooden door, heavy iron bolts on one side and a Judas window in the centre. Wheatcroft saw me looking at it. “That’s the door to Hitler’s cell in Landsberg. Where he wrote Mein Kampf. I was in the area.” A lot of Wheatcroft’s stories start like this – he seems to have a genius for proximity. “I found out that the prison was being pulled down. I drove there, parked up and watched the demolition. At lunch I followed the builders to the pub and bought them a round. I did it three days in a row and by the end of it, I drove off with the door, some bricks and the iron bars from his cell.” It was the first time he had mentioned Hitler by name. We paused for a moment by the dark door with its black bars, then moved on.

Sometimes the stories of search and recovery were far more interesting than the objects themselves. Near the door sat a trio of rusty wine racks. “They were Hitler’s,” he said, laying a proprietary hand upon the nearest one. “We pulled them out of the ruins of the Berghof [Hitler’s home in Berchtesgaden] in May 1989. The whole place was dynamited in ’52, but my friend Adrian and I climbed through the ruins of the garage and down through air vents to get in. You can still walk through all of the underground levels. We made our way by torchlight through laundry rooms, central heating service areas. Then a bowling alley with big signs for Coke all over it. Hitler loved to drink Coke. We brought back these wine racks.”

Later, among engine parts and ironwork, I came across a massive bust of Hitler, sitting on the floor next to a condom vending machine (“I collect pub memorabilia, too,” Wheatcroft explained). “I have the largest collection of Hitler heads in the world,” he said, a refrain that returned again and again. “This one came from a ruined castle in Austria. I bought it from the town council.”

“Things have the longest memories of all,” says the introduction to a recent essay by Teju Cole, “beneath their stillness, they are alive with the terrors they have witnessed.” This is what you feel in the presence of the Wheatcroft Collection – a sense of great proximity to history, to horror, an uncanny feeling that the objects know more than they are letting on.

Wheatcroft’s home sits behind high walls and heavy gates. There is a pond, its surface stirred by the fingers of a willow tree. A spiky black mine bobs along one edge. The house is huge and modern and somehow without logic, as if wings and extensions have been appended to the main structure willy-nilly. When I visited, it was late afternoon, a winter moon climbing the sky. Behind the house, apple trees hung heavy with fruit. A Krupp submarine cannon stood sentry outside the back door. One of the outer walls was set with wide maroon half-moons of iron work, inlaid with obscure runic symbols. “They were from the top of the officers’ gates to Buchenwald,” Wheatcroft told me in an offhand manner. “I’ve got replica gates to Auschwitz – Arbeit Macht Frei – over there.” He gestured into the gloaming.

I had first heard about Wheatcroft from my aunt Gay, who, as a rather half-hearted expat estate agent, sold him a rambling chateau near Limoges. They subsequently enjoyed (or endured) a brief, doomed love affair. Despite the inevitable break-up, my father kept in touch with Wheatcroft and, several years ago, was invited to his home. After a drink in the pub-cum-officers’ mess that Wheatcroft has built adjacent to his dining room, my dad was shown to the guest apartment. It was remarkable, he said, mostly for the furniture. That night, my dad slept in Hermann Göring’s favourite bed, from Carinhall hunting lodge, made of walnut wood and carved with a constellation of swastikas. There were glassy eyed deer heads and tusky boars on the walls, wolf-skin rugs on the floor. My father was a little spooked, but mostly intrigued. In an email soon after, he described Wheatcroft to me as “absurdly decent, almost unnaturally friendly”.

Darkness had fallen as we stepped into the immense, two-storey barn conversion behind his home. It was the largest of the network of buildings surrounding the house, and wore a fresh coat of paint and shiny new locks on the doors. As we walked inside, Wheatcroft turned to me with a thin smile, and I could tell that he was excited. “I have to have strict rules in my life,” he said, “I don’t show many people the collection, because not many people can understand the motives behind it, people don’t understand my values.” He kept making these tentative passes at the stigma attached to his obsession, as if at once baffled by those who might find his collection distasteful, and desperately keen to defend himself, and it.

The lower level of the building contained a now-familiar range of tanks and cars, including the Mercedes G4 Wheatcroft saw as a child in Monaco. “I cried and cried because my dad wouldn’t buy me this car. Now, almost 50 years later, I’ve finally got it.” On the walls huge iron swastikas hung, street-signs for Adolf Hitler Strasse and Adolf Hitler Platz, posters of Hitler with “Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer” written beneath. “That’s from Wagner’s family home,” he told me, pointing to a massive iron eagle spreading its wings over a swastika. It was studded with bullet holes. “I was in a scrap yard in Germany when a feller came in who’d been clearing out the Wagner estate and had come upon this. Bought it straight from him.”

We climbed a narrow flight of stairs to an airy upper level, and I felt that I had moved deeper into the labyrinth of Wheatcroft’s obsession. In the long, gabled hall were dozens of mannequins, all in Nazi uniform. Some were dressed as Hitler Youth, some as SS officers, others as Wehrmacht soldiers. It was bubble still, the mannequins perched as if frozen in flight, a sleeping Nazi Caerleon. One wall was taken up with machine guns, rifles and rocket launchers in serried rows. The walls were plastered with sketches by Hitler, Albert Speer and some rather good nudes by Göring’s chauffeur. On cluttered display tables sat a scale model of Hitler’s mountain eyrie the Kehlsteinhaus, a twisted machine gun from Hess’s crashed plane, the commandant’s phone from Buchenwald, hundreds of helmets, mortars and shells, wirelesses, Enigma machines, and searchlights, all jostling for attention. Rail after rail of uniforms marched into the distance. “I brought David Ayer in here when he was researching Fury,” Wheatcroft told me. “He offered to buy the whole lot there and then. When I said no he offered me 30 grand for this.” He showed me a fairly ordinary-looking camouflage tunic. “He knows his stuff.” We were standing in front of signed photographs of Hitler and Göring. “I think I could give up everything else,” he said, “the cars, the tanks, the guns, as long as I could still have Adolf and Hermann. They’re my real love.”

I asked Wheatcroft whether he was worried about what people might read into his fascination with Nazism. Other notable collectors, I pointed out, were the bankrupt and discredited David Irving and Lemmy from Motörhead. “I try not to answer when people accuse me of being a Nazi,” he said. “I tend to turn my back and leave them looking silly. I think Hitler and Göring were such fascinating characters in so many ways. Hitler’s eye for quality was just extraordinary.” He swept his arm across the army of motionless Nazis surrounding us, taking in the uniforms and the bayonets, the dimly glimmering guns and medals. “More than that, though,” he continued, “I want to preserve things. I want to show the next generation how it actually was. And this collection is a memento for those who didn’t come back. It’s the sense of history you get from these objects, the conversations that went on around them, the way they give you a link to the past. It’s a very special feeling.”

We walked around the rest of the exhibition, stopping for a moment by a nondescript green backpack. “There’s a story behind this,” he said. “I found a roll of undeveloped film in it. I’d only bought the backpack to hang on a mannequin, but inside was this film. I had it developed and there were five unpublished pictures of Bergen-Belsen on it. It must have been very soon after the liberation, because there were bulldozers moving piles of bodies.”

The most treasured pieces of Wheatcroft’s collection are kept in his house, a maze-like place, low-ceilinged and full of staircases, corridors that turn back on themselves, hidden doorways and secret rooms. As soon as we entered through the back door, he began to apologise for the state of the place. “I’ve been trying to get it all in order, but there just aren’t the hours in the day.” In the drawing room there was a handsome walnut case in which sat Eva Braun’s gramophone and record collection. We walked through to the snooker room, which housed a selection of Hitler’s furniture, as well as two motorbikes. The room was so cluttered that we could not move further than the doorway.

“I picked up all of Hitler’s furniture at a guesthouse in Linz,” Wheatcroft told me. “The owner’s father’s dying wish had been that a certain room should be kept locked. I knew Hitler had lived there and so finally persuaded him to open it and it was exactly as it had been when Hitler slept in the room. On the desk there was a blotter covered in Hitler’s signatures in reverse, the drawers were full of signed copies of Mein Kampf. I bought it all. I sleep in the bed, although I’ve changed the mattress.” A shy, conspiratorial smile.

We made our way through to the galleried dining room, where a wax figure of Hitler stood on the balcony, surveying us coldly. There was a rustic, beer-hall feel to the place. On the table sat flugelhorns and euphoniums, trumpets and drums. “I’ve got the largest collection of Third Reich military instruments in the world,” Wheatcroft told me. Of course he did. There was Mengele’s grandfather clock, topped with a depressed-looking bear. “I had trouble getting that out of Argentina. I finally had it smuggled out as tractor parts to the Massey-Ferguson factory in Coventry.” Wheatcroft briefly opened a door to show the pub he had built for himself. Even here there was a Third Reich theme – the cellar door was originally from the Berghof.

The electricity was off in one wing of the house, and we made our way in dim light through a conservatory where rows of Hitler heads stared blindly across at each other. Every wall bore a portrait of the Führer, or of Göring, until the two men felt so present and ubiquitous that they were almost alive. In a well at the bottom of a spiral staircase, Wheatcroft paused beneath a full-length portrait of Hitler. “This was his favourite painting of himself, the one used for stamps and official reproductions.” The Führer looked peacockish and preening, a snooty tilt to his head. We climbed the stairs to find more pictures of Hitler on the walls, swastikas and iron crosses, a faintly Egyptian statuette given by Hitler to Peron, an oil portrait of Eva Braun signed by Hitler. Paintings were stacked against walls, bubble wrap was everywhere. We picked our way between the artefacts, stepping over statuary and half-unpacked boxes. I found myself imagining the house in a decade’s time, when no doors would open, no light come in through the windows, when the collection would have swallowed every last corner, and I could picture Wheatcroft, quite happy, living in a caravan in the garden.

We passed along more shadowy corridors, through a door hidden in a bookshelf and up another winding staircase, until we found ourselves in an unexceptional bedroom, a single unshaded light in the ceiling illuminating piles of uniforms. On the walls of the room were a host of gaudy naif paintings and objects in display cases. “They all belonged to the Krays,” Wheatcroft said. “That’s my other great love, the Kray twins.” There was a chill in the air in this room, under the swinging white light of the lamp. Somehow this collection of gangland trinkets and their casual brutality seemed to undermine the lofty aspirations of the rest of the collection. There was Ronnie’s death certificate on the wall, his framed false teeth, the gun he used for one of his first murders. On the mantelpiece in the corner of the room there was a small library of books about the twins. Further inspection of the walls revealed the Krays’ cufflinks and rings, spoons from Broadmoor, some early mugshots. Wheatcroft reached into a cupboard and pulled out Hitler’s white dress suit with careful, supplicatory hands.

“I was in Munich with a dealer,” he said, showing me the tailor’s label, which read Reichsführer Adolf Hitler in looping cursive. “We had a call to go and visit a lawyer, who had some connection to Eva Braun. In 1944, Eva Braun had deposited a suitcase in a fireproof safe. He quoted me a price, contents unseen. The case was locked with no key. We drove to Hamburg and had a locksmith open it. Inside were two full sets of Hitler’s suits, including this one, two Sam Browne belts, two pairs of his shoes, two bundles of love letters written by Hitler to Eva, two sketches of Eva naked, sunbathing, two self-propelling pencils. A pair of AH-monogrammed eyeglasses. A pair of monogrammed champagne flutes. A painting of a Vienna cityscape by Hitler that he must have given to Eva. I was in a dream world. The greatest find of my collecting career.”

Wheatcroft drove me to the station under a wide, star-filled night. “When David Ayer offered to buy the collection, I almost said yes,” he told me, his eyes on the road. “Just so it wouldn’t be my problem any more. I tried to buy the house in which Hitler was born in Braunau, I thought I could move the collection there, turn it into a museum of the Third Reich. The Austrian government must have Googled my name. They said no immediately. They didn’t want it to become a shrine. It’s so hard to know what to do with all the stuff. I really do feel like I’m just a caretaker until the next person comes along, but I must display it, I must get it out into the public – I understand that.” We pulled into the station car park and, with a wave, he drove off into the night.

On the way home I read Wheatcroft’s father’s autobiography and then stared out of the train window, feeling the events of the day working themselves upon me. The strange thing was not the weirdness of it all, but the normality. I really don’t believe that Wheatcroft is anything other than what he seems – a fanatical collector. I had expected a closet Nazi, a wild-eyed goosestepper, and instead I had met a man wrestling with a hobby that had become an obsession and was now a millstone. Collecting was like a disease for him, the prospect of completion tantalisingly near but always just out of reach. If he was mad, it wasn’t the madness of the fulminating antisemite, rather the mania of the collector.

A pair of Ronnie Kray’s shoes. Photograph: David Sillitoe for the Guardian

Many would question whether artefacts such as those in the Wheatcroft Collection ought to be preserved at all, let alone exhibited in public. Should we really be queueing up to marvel at these emblems of what Primo Levi called the Nazis’ “histrionic arts”? It is, perhaps, the very darkness of these objects, their proximity to real evil, that attracts collectors (and that keeps novelists and filmmakers returning to the years 1939-45 for material). In the conflicting narratives and counter-narratives of history, there is something satisfyingly simple about the evil of the Nazis, the schoolboy Manichaeism of the second world war. Later, Wheatcroft would tell me that his earliest memory was of lining up Tonka tanks on his bedroom floor, watching the ranks of Shermans and Panzers and Crusaders facing off against each other, a childish battle of good and evil.

After I sent him a copy of Laurent Binet’s 2010 novel HHhH, a brilliant retelling of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the principal architects of the Holocaust, Wheatcroft emailed me with news of an astonishing new find in the house of a retired diplomat. “I’d fully intended to ease up on the collecting,” he told me, “to concentrate on cataloguing, on getting the collection out there, but actually some of the things I’ve discovered since I saw you last, I’ve just had to buy. Big-value items, but you just have to forget about that because of the sheer rarity value. It’s compounded the problem really, because they were all massive things.”

His latest find, he said, was a collection of Nazi artefacts brought to his attention by someone he had met at an auction a few years back. The story is classic Wheatcroft – a mixture of luck and happenstance and chutzpah that appears to have turned up objects of genuine historical interest. “This chap told me that his best friend was a plumber and was working on a big house in Cornwall. The widow was trying to sort things out. The plumber had seen that in the garden there were all sorts of Nazi statues. He sent me a picture of one of the statues, which was a massive 5 ½ foot stone eagle that came from Berchtesgaden. I did a deal and bought it, and after that sale my contact was shown a whole range of other objects by the widow. It turned out that this house was a treasure trove. There’s an enormous amount I’m trying to get hold of now. I can’t say an awful lot, but it’s one of the most important finds of recent times.”

The owner of the house had just passed away; he was apparently a senior British diplomat who, in his regular trips to Germany in the lead-up to the war, amassed a sizable collection of Nazi memorabilia. He continued to collect after the war had finished, the most interesting items hidden in a safe room behind a secret panel. “It’s stunning,” Wheatcroft told me, by telephone, his voice fizzing with excitement. “There’s a series of handwritten letters between Hitler and Churchill. They were writing to each other about the route the war was taking. Discussions of a non-aggression pact. This man had copied things and removed them on a day-to-day basis over the course of the war. A complete breach of the Official Secrets Act, but mindblowing.” The authenticity of the papers, of course, has not yet been confirmed – but if they are real, they could secure Wheatcroft a place in the history books. “Although it’s never been about me,” he insisted.

It seems our meeting in the winter stirred something in Wheatcroft, a realisation that there were duties that came with owning the objects in his collection, obligations to the past and present that had become burdensome to him. “It’s the objects,” he told me repeatedly, “the history.” It also seemed as if Wheatcroft’s halfhearted attempts to bring his collection to a wider public had been given a much-needed fillip. “An awful lot has changed since I saw you,” he told me when we spoke in late spring. “It refocused me, talking to you about it. It made me think about how much time has gone by. I’ve spent, I suppose, 50 years as a collector just plodding along, and I’ve suddenly realised that there’s more time behind than ahead, and I need to do something about it. I’ve pressed several expensive buttons in order to get some of my more valuable pieces restored. Because you did just make me think what’s the point of owning these things if no one’s ever going to see them?”

THE LONG READ

No comments:

Post a Comment