IN CONVERSATION

CLAUDE PICASSO ANDJOHN RICHARDSON

Picasso biographer and family friend Sir John Richardson sits down with Claude Picasso for a wide-ranging conversation. The two discuss Claude’s photography, his enjoyment of vintage car racing, his encounters with Willem de Kooning, and the future of scholarship related to his father, Pablo Picasso.

John Richardson

Winter 2018

JOHN RICHARDSON So, what brings you to New York?

CLAUDE PICASSO Well, tomorrow is my birthday and I thought I’d spend it with [my mother] Françoise [Gilot]. It’s amusing because we’re exactly twenty-five years apart, so it’s easy to remember: When I turned twenty-five, she turned fifty. When she turned seventy-five, I was fifty. This week she said, “And what are you going to be? Oh, seventy-two? So it means I’ll be a hundred” [laughter]. I said, “Not yet.”

JR We have lunch with her as often as we can and she’s still so sharp and full of life. Did your grandparents on the Gilot side live to as advanced an age?

CP My grandfather didn’t live to be so old, on account of the wars—he spent four years, more or less, in the trenches during the First World War and then in the Second World War he was called back. Can you imagine? He suffered from rheumatism, which happened when you lived in the trenches, so the end of his life wasn’t pleasant. But Françoise’s mother lived to be eighty-six, and her grandmother also lived to be quite old.

JR Good genes.

CP My grandfather was interesting because he was an agronomical engineer, which meant that he was automatically made an officer in the army. But he refused to be an officer. He said, “If I’m going to be in this war, I want to be just like the other men.”

JR He was principled.

CP Yes, exactly. People were that way in those days. But my grandmother’s two brothers also went to war and both of them were made officers, so they had to dress up in this absurdly extravagant way, you know, red and blue and feathers and whatnot. And their outfits were entirely made by Hermès [laughter].

JR When I went to sign up for service, the doctors examined me and found I had a disease I didn’t know, something that had never declared itself. They said, “Oh, you can never go to war,” and I pretended, “Oh please, let me go to war! Please! Oh, this is awful, my family will be so upset.” “You cannot go to war.” I said, “ . . . Are you sure?” [laughter] So I ended up an air raid warden—we used to parade Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens, look up and see what was happening in the sky, but we were just firemen, basically.

CP Wasn’t your father quite important in the military?

JR And knighted for it. But my father was seventy-two when I was born, and died when I was six. My grandfather was born in, I think, 1815 or 1817, so I have this ludicrous sort of—I go back in two generations to the Napoleonic Wars [laughter]. I’m a bit of a freak in that respect—I don’t fit into any kind of ordinary timetable.

CP You are timeless! [laughter]

JR And here I am, age ninety-four, still in reasonably good shape and fully intent to go on until I’m a hundred.

CP That’s a bit like my family. My grandfather on the Picasso side was born in the early nineteenth century, then I was born when my father was quite old; he was sixty-five. Now I have a little son who’s ten. So it’s two centuries, you know, a span of two centuries.

JR And you and I go back a long way as well.

I NEVER HELPED ANYONE CONDEMN PICASSO, BUT IT’S NOT LIKE I WAS A DEFENDER OF THE TRUTH OR SOMETHING. PICASSO COULD STAND ON HIS OWN TWO LEGS.

Claude Picasso |

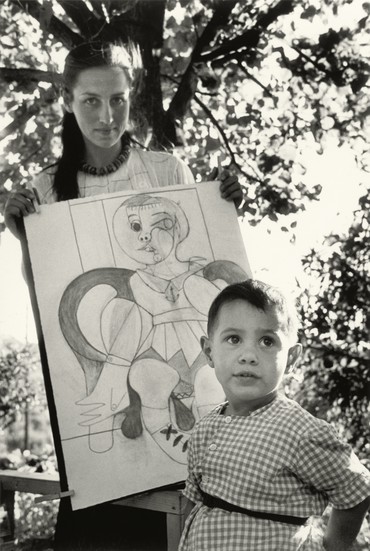

| Robert Capa, Françoise Gilot and Claude Picasso, Vallauris, France, 1949 © Cornell Capa © International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos |

CP I remember when I was quite young that when you and Douglas [Cooper] used to come to visit, you would wear shorts, which I thought were only for children at the time [laughter].

JR [laughs] That’s very embarrassing. I thought I looked okay in shorts, but Douglas —

CP That’s the point—there was one young man in shorts who looked quite spiffy and another one who was a bit more dubious [laughter]. Coming up the steps—it was quite a sight for me. We were told that you were Australians, both of you.

JR Douglas’s father was Australian, so that was partly true.

CP My father said, “You see these two—the Australians are coming” [laughter]. So I just thought Australians were very exotic. I had no idea what Australia was, but they wore shorts there [laughter]. And you wore very short shorts.

JR Oh dear [laughter].

CP It’s strange that I picked up on this with you, because I didn’t pay that much attention to other people. But I always thought you were fun, both of you. Most people who came to visit absolutely ignored us, but you would actually speak with us, the children. So we thought, “Ah—we matter.”

JR Yes, of course you mattered—we loved visiting with you. It was almost as if there were three generations—you and [your sister] Paloma and [your step-sister, Jacqueline Roque’s daughter] Cathy were there; [your half-brother, Olga Khokhlova’s son] Paul, Françoise, Jacqueline, and I were all around the same age, and then there was your father, and friends like [Henri] Matisse and [Jean] Cocteau, who’d known each other forty-plus years. And Picasso clearly loved to have children around. We always took care to speak with Cathy especially, as we felt it must have been hard to suddenly join this complicated family of the most famous artist in the world. But it was a magical time and a magical household.

Do you still take photographs?

CP A little bit, yes. I’m trying to reconnect with photography at the moment, so I’ve been looking at the work I did before and trying to see if there’s some sort of through line or feeling that I seem to have pursued by accident. I’d like to try and start from there, but it’s not so clear.

JR But why did you stop in the first place? Or did you feel that you stopped at some point?

CP Basically, I stopped because I couldn’t work professionally anymore, I was too busy with the estate and running the Picasso Administration. When I was still quite young, my brother, Paul, said it was fortunate I was there because I’d “solve the future,” or “solve everything.” It was a strange thing to say, but it turns out that’s what I ended up doing—it’s sort of shocking. I never expected or desired to have any kind of role like this, or have any influence over my father’s legacy. Paul also said, shortly before he died, “You know, if we’re in the shit we’re in, it’s all your fault” [laughter]. And he and Françoise laughed like crazy, because, you know, they were such good friends. It was typical of Paul to say something like that, his sense of humor. So because of the Picasso Administration, little by little, I had to quit photography. Not all of a sudden but little by little.

JR How did you first meet Richard Avedon?

CP When he photographed Paloma and me.

JR Professionally you’re the head of the Picasso Administration, but you’re also a bit of a professional race car driver. How long have you been racing?

CP I started very late. I got involved with cars and racing because of the photographer David Douglas Duncan. One day I met him by chance and he told me he was going to sell his car, the famous Mercedes Gullwing. I said, “You don’t have to do that. It’s your old horse. You can’t just throw him out of the house” [laughter]. He said, “No, no, I decided and I’m going to sell it to so-and-so.” And I said, “No, not to him, forget it, this car is mine. If you’re really going to let it go, it’s mine. Here is a check.” So I ended up with this old piece of junk and I said to a friend of mine, “I just acquired this thing. What do I do with it now?” He told me of these races for old cars—“vintage,” they call them—and I entered one race and then another. But it’s a complicated car—it’s heavy and difficult, so I started looking for a lighter car and then another and I kept switching cars and getting better at driving, I took classes and ended up doing track and rally and so on, and I became, you know, little by little, very involved. And so now I am semiprofessional. But vintage! [laughter]

JR How many races do you do in a year?

CP I used to do up to ten or twelve, which took up a lot of time, so I had to cut back. Now I specialize in certain races, like one in Morocco in the desert, or in Finland on the ice and the snow—racing on the frozen sea or in the woods. Quite dangerous, actually, but I became very good at these difficult races.

JR Do you still own the Gullwing? You must remember it from your childhood, because Duncan always had it around La Californie during the years he was photographing Picasso?

CP Yes, of course. That’s why I said, “That’s my car” [laughter]. And I still own it! In a way, one of the reasons I became a photographer is that Duncan was always around, clicking away, and I thought, oh, this would be an interesting occupation. When I was about seventeen, he very kindly gave me a professional camera.

JR He gave you one? Do you remember what it was?

CP A Nikon. I still have it, too!

JR Do you keep an archive of your photographs?

CP I do, but I don’t have all of them, I’ve lost a lot of things over the years. In the old days, the magazines and newspapers I worked for used to keep them.

JR Life magazine sent you on assignment to photograph Willem de Kooning when he returned to the Netherlands for the very first time since emigrating to New York.

CP For his big exhibition in 1968, yes. I had been sent by Life magazine to London to cover a rock band called the Incredible String Band, which wasn’t that incredible [laughter]. I was traveling around with them and it was the most awful experience. They lived as a commune in Wales, they lived with the animals and were very laid back, really hard-core hippies, and I was trying to get this thing to look like something presentable for Life magazine. At the time it was still a kind of old-fashioned magazine, so I always wore a suit and tie, I had to cut my hair and—you know, the works—but I was young so supposedly I would fit in [laughs].

So I was there with not much of a job and not much to do, actually, so I got saved by de Kooning coming to Holland. I was sent there because I knew him and his daughter—and there I fit in! De Kooning was very proper and wore a tie and we went around to all the museums and met up with a friend from his youth in Rotterdam and I just kept shooting. They were house painters when they were young men and we walked around looking at houses and how well painted they were [laughter].

JR Do you still have the images of that trip?

CP A few that are not so exciting.

JR How did you first meet de Kooning?

CP I had met him in the Hamptons—I used to go there often when I lived in New York in the 1960s. In those days it was a very small community. There were always get-togethers—the artists’ and writers’ picnic, or the artists’ and writers’ football match. Nobody knew how to play [laughter]. It was probably just an excuse to get drunk and have fun, so we’d meet on the beach or at someplace or other. And so you met everyone, because it was only a handful of people out there; Lee Krasner was around, Jimmy Ernst, Conrad Marca-Relli, and less well-known people you haven’t even heard of.

JR This was the ’60s and early ’70s? I think you got the best time out there.

CP Yes, you can imagine. We had a party for the landing on the moon [laughter]. We had a small television set and took it into the garden and everyone was there, sitting around drinking and laughing.

JR Have you ever written about that time?

CP No, but I wrote some other, connected pieces. I published a piece in the Saturday Review, which was fun—they were trying to make Saturday Review a little more exciting so I was hired to do something. I thought, OK, people collect art, so I’ll investigate what kinds of things artists collect. I went around to all the gang, and of course I had to find artists who collect something different from their buddies. That led me to Andy [Warhol], who collected just about everything [laughter]. The project was so funny and unexpected and they included a photograph of Andy with his cookie jars on the cover.

I’VE COME HERE TODAY WITH REAL JOY AND EMOTION, AND IT’S NOT BECAUSE I’M NOSTALGIC ABOUT THE PAST, I’M NOT AT ALL—I’M VACCINATED AGAINST IT.

Claude PicassoJR I’m working on a Warhol exhibition for Gagosian in London we’ll put on sometime next year—society portraits. They’re fascinating—there’s so much invention and variety, they aren’t “simply portraits” at all. It’s a deceptively simple subject. The portraits he makes in the late 1960s are completely different from the ones he makes in the ’70s and ’80s—he almost progresses through “periods” with the portraits alone. Yet, as his interest in portraiture develops, he becomes a sort of self-conscious portrait painter of a traditional kind. I don’t remember Picasso ever saying anything about Andy Warhol, do you?

CP No.

JR I mean, I think he just didn’t realize.

CP Yes, I think he just wasn’t curious. But you remember that Andy came to prominence just about the time I was sent away, after my mother’s memoir was published. I didn’t see my father after that. Then maybe two, three years later, I came to New York and discovered the scene here. I always thought it was a pity that I couldn’t come home and tell him about it.

JR Yes.

CP At least to see what it would have meant for him to hear about it. Because I met all these people, I was living in the midst of the whole art scene. But it wasn’t possible. Pierre Matisse used to write letters to his father [Henri] about the goings-on in New York, and he also visited my father, so may have said something, but the reactions we don’t know about.

JR Picasso was rather insulated in those years—but perhaps that was what he wanted, to keep on working and concentrate his energy to keep creating until the very end. I feel it too: at my age, I’m still full of beans and ready to get down to work every day, but I have a great team of researchers to help me and we keep each other on track. They keep distractions at bay. I appreciate now that it was heroic of Jacqueline to give Picasso the peace and protection to create. But that was also Jacqueline’s nature; I knew she was the right woman for Picasso—not only because she was very beautiful and just his type, but she also had the temperament to take him on and to keep up. I mean, Picasso was a lot of work, and she was tireless. One may slow down, but one never imagines giving in and stopping. At ninety-four, I’ve just about finished volume four of the biography, which brings us up to 1943—but the problem is we keep uncovering masses of new stuff to include, so I’m constantly going back and adding and revising.

CP You know, John, I pick up information or I meet people, but I’m not on a mission—people are always asking me to write about my life or past anecdotes, and I hate that, because it doesn’t add anything—just one more anecdote, it’s boring. So I meet people and find out useful things, but not the way you collect information for the book you’re writing. I can write, but I don’t want to write about that. I’ll leave it to you [laughter].

JR You say you never got to speak to your father about the New York scene and the artists you met—

CP No, because I was out of the picture.

JR But those artists must have been interested in talking to you about Picasso?

CP Not so much. People would come to me and complain, in a way [laughter]. “I had nothing to do with it—don’t blame me!” But he was always in the mind of the people here in New York, like a great classic, or a frustrating, castrating image. I was probably too young, I was extremely patient with everyone—I listened, and I didn’t comment or provoke them in any way, I never helped anyone condemn Picasso, but it’s not like I was a defender of the truth or something. Picasso could stand on his own two legs.

JR He certainly could, yes.

CP People would come to me and say, “Your father this-and-that,” and I’d always reply, “Picasso this-and-that”—to make people understand they were discussing something I could discuss, not something personal. Because otherwise it’s a mess and the discussion is polluted.

If Picasso didn’t appear too curious about contemporary painters of the 1950s, especially in America, that was a shame, because those artists still referred openly to Picasso, at least in talking about the problems of painting and abstraction. But then there was a shift, and contemporary artists became Conceptual, Minimal, or made Land art—it would be curious to find out how they felt about Picasso. They would have seen his giant concrete Sylvette, which was installed near New York University in the mid-’60s—Picasso always wanted to make monumental sculptures. Scale and materials were languages they could have spoken with Picasso.

JR So young guys like Mr. [Richard] Serra and Mr. [Michael] Heizer would have been aware of those works.

CP I would think so. But what was considered Conceptual art was moving closer to [Marcel] Duchamp, and Duchamp being present around here, he had a sort of moral influence. I’m not sure how well anyone understood Duchamp, but many gravitated toward him and went to almost extreme measures to avoid Picasso. But that attitude misses the idea that Picasso was a bit of a philosopher, right? He had a philosophical approach to breaking barriers and to how art can operate—the kind of philosophy that later Conceptual artists were engaging with. It’s not all Duchamp. So it’s interesting that Picasso ignored contemporary art, but the artists did not ignore him.

JR I always think young artists should try to wrestle with Picasso—move toward him or away, but engage somehow. It’s far from easy. Any new, bright young scholars working on Picasso coming up, who’ve got a different angle?

CP Mostly they’re interested in little subjects. I find some interesting, but they focus on one small aspect and develop a theory, sometimes right, sometimes wrong, sometimes crazy [laughter]. But that’s nice too. Because why not?

JR Yes, exactly. It’s a way to explore.

CP I have a feeling there are going to be more, because there are too many people involved with contemporary art, and in the end, it could be a little unsatisfying. So there may be people coming back to the nitty-gritty of history, but that’s also more difficult. It’s a hard job. And there’s still a lot to learn from Picasso.

There’s a story I sometimes tell, something that was very important for me, determining for my attitude. My father and I were at a bullfight in Nîmes or Arles, and it was El Cordobés, the bullfighter, who had a very unacademic way of bullfighting. So after the bullfight my father and I always had these big discussions dissecting what had happened in the ring, and I was complaining that El Cordobés was always doing strange things and that he didn’t kill the bull properly and wasn’t fighting in the proper way. So my father said, “What are you saying? You should like him. He’s a Beatle.” Like the Beatles! [laughter] And then he said, “What would ever have happened if I’d painted like Delacroix?” So you know, “Pfft.” And I thought, yeah, right, okay. Okay, it’s important to take another risk.

JR That is so like Picasso. Claude, it’s such a joy to see you.

CP Yes, and it’s such a pleasure to have known each other for so long.

JR Yes, it is very much for me.

CP It’s really special, because I don’t know very many people who are still around and who are as interesting and amusing and fun and pleasant to be with, and always a pleasure to spend time with. It’s very difficult, John, it’s very rare, you know. I’ve come here today with real joy and emotion, and it’s not because I’m nostalgic about the past, I’m not at all—I’m vaccinated against it [laughter]—but really, it’s just because we can have a pleasant conversation and a bit of fun, and we can talk about anything, lightly and also profoundly. Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment