|

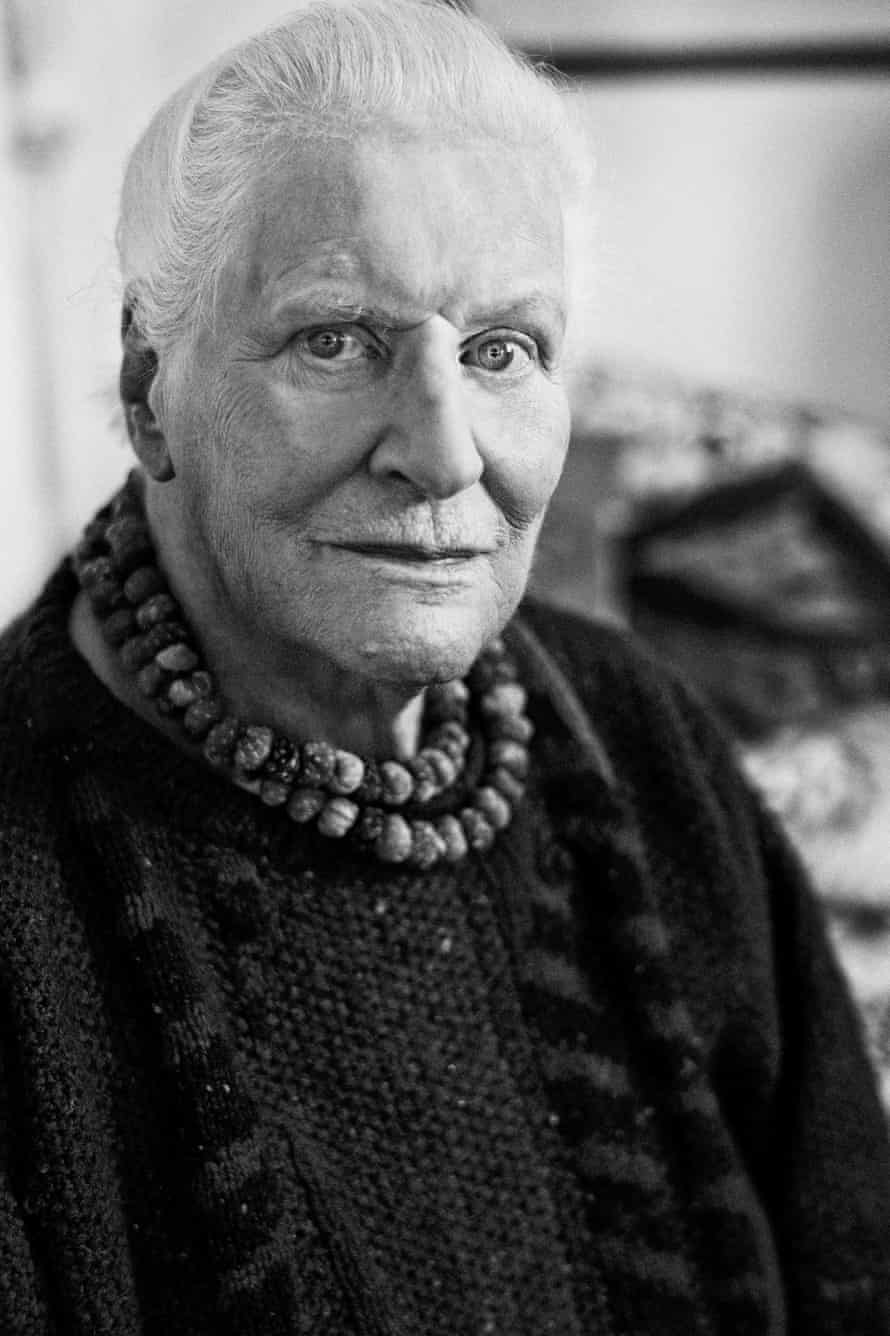

| Diana Athill at the old people’s home where she has lived for several years. Photograph: Sarah Lee |

The long readDiana Athill: It’s silly to be frightened of being dead

At the age of 96, the legendary editor Diana Athill writes, the idea of death has never been less alarming. The process of dying is another matter

Diana AthillTuesday 24 September 2014

Back in the 1920s my mother never went to a funeral if she could help it, and was horrified when she heard of children being exposed to such an ordeal, and my father vanished from the room if death was mentioned; very much later, in the 1960s, when the publishers in which I was a partner brought out a beautiful and amusing book about the trappings of death, booksellers refused to stock something so “morbid”. I was born in December 1917, so was fully immersed in this refusal to contemplate death. Indeed it was not until more than 30 years later, when I had to visit a coroner’s office to identify a woman who had been found dead, that I thought for the first time how extraordinary – indeed how ridiculous – it was to have lived for so long without ever having seen a dead body. I have heard it suggested that this recoil from the subject was a result of the first world war filling everyone’s minds with an acute and appalled awareness of death, but my own explanation was, and still is, that it was a pendulum-swing away from the preceding century’s obsession with the subject – the relish for mourning, ranging from solemn viewing of the corpse by young and old alike, to passionate concern about the exact degree of blackness to be worn, and for how long (for the rest of your days if you were a widow). A mood so extreme surely had to result in a strong reaction.

It seems to me that what influences the consciousness in wartime is not death. It is killing. And no, they are not the same thing.

Death is the inevitable end of an individual object’s existence – I don’t say “end of life” because it is a part of life. Everything begins, develops – if animal or vegetable, breeds – then fades away: everything, not just humans, animals, plants, but things which seem to us eternal, such as rocks. Mountains wear down from jagged peaks to flatness. Even planets decay. That natural process is death. Killing is the obscene intervention of violence, the violation which prevents a human being or any other animal from reaching death as it should be reached. Killing certainly did affect the minds of those exposed to the first world war. It shocked most of them into silence: many of the men who survived fighting in it never spoke of it, and I think it had the same effect on most of those the men returned to. It was too dreadful. They shut down on it.

My maternal grandparents’ house, in which the children of my generation spent all their holidays, and where we stayed if our empire-serving parents were abroad in some place inhospitable to the young, was typical of those times in that the only music-making objects in it were an upright piano and a small wind-up record player that had belonged to my uncle when he was a boy: a condition probably unthinkable to children today. There was no pop music because there were no teenagers, only children and grownups. Certainly once the children had turned 12 they began being restive (the grownups called it “the awkward age”) but there was little to be done about it. There were music-hall songs and dance music, but they could only come into a home via sheet music and if there was someone there who could play the piano, and the limit of adult piano-playing in our family was nursery rhymes to amuse the little ones. A hint of the future might have been detected in the eagerness with which we children fell on Uncle Billy’s little “gramaphone”, which had been forgotten by the grownups. We listened over and over again to the few records that went with it – some Gilbert and Sullivan songs and two or three spirituals sung by Paul Robeson. Right at the back of the cupboard where they lived I once found another record, which turned out to be a wartime song, a comic and rather witty version of Who Killed Cock Robin called Who Killed Bill Kaiser. Although I was born before the war’s end, it was as remote and unreal to me as the wars of the roses, so I was as thrilled as I would have been if I had dug up a medieval helmet, and ran to show the record to my mother. All she said was, “That old thing – is it still there?” It was a shock to come up so suddenly against the fact that what to me was history, to her was just something from the day before yesterday. Absolutely no trace of that day before yesterday had been injected into my consciousness by my elders, so whatever I was to feel about death, it had nothing to do with war.

My own experience of the second world war confirmed this. Before it started, during the horrible months when we could all feel it coming, I said to a friend: “If it does start I think I’ll kill myself.” (Although the preceding war had been little talked about, poets and novelists had written about it, so we were fully aware that a repetition ought to be unthinkable.) My friend replied, “Killing yourself to avoid being killed would be a bit silly,” and I felt sadly that she was being obtuse. It was not the prospect of being killed that was distressing me, it was having to know this obscenity about life. And that, not fear of death, was what polluted one’s consciousness all through the war, so that the moment it was over we too shut down on it.

Because we did shut down. “It’s over!” That knowledge wiped out any other feeling. Although I have never doubted (heaven knows why) that we were going to win the abomination, there had been times when I had not thought – perhaps “thought” is wrong – when I had not felt it possible that it would ever end. In one’s twenties a year is a very long time, and there had been so many of them. It astounds me now when I hear or read people describing the 1950s as dreary, because to me they were wonderful. What did it matter that rationing dragged on? We were getting more for our coupons every day – it was slow of course, but how could it be otherwise after what we had been through? Now we had our new Labour government, we had the National Health Service (how can anyone forget what a miracle that was?), we had Dior’s ravishing New Look, we could travel again and who cared if we could take no more than £25 with us when it was so amazing what one could do on £25 in France or Italy or Greece. I could see no reason to be anything but happy, and death was just something that would occur when I was old – and which was not, and never had been, frightening.

That this was true, I owe to Montaigne. I can’t remember when I read, or was told, that he considered it a good thing to spend a short time every day thinking about death, thus getting used to its inevitability and coming to understand that something inevitable is natural and can’t be too bad, but it was in my early teens, and it struck me as a sensible idea. Of course I didn’t set out to think about death in a regular way every day, but I did think about it quite often, and sure enough, it worked. Why coming to see death’s naturalness should have caused belief in an afterlife to melt away, I am unsure, but it did. Probably that belief had been no more than an unexamined acceptance of something said by a grownup: in a child’s life there are many things more important to question than the probability of reuniting after death with other dead people – ideas that are tucked away on a back shelf of the mind like some object for which one has no use at present.

When I was 16, I had my appendix removed: an operation common in those days which seems to have gone out of fashion. Going under the anaesthetic, which was chloroform, caused an interesting confrontation with that particular idea. As a little girl I had occasionally suspected that there was a monster under my bed waiting to come out and get me, scaring myself so much that I had to be calmed down and assured that I was imagining it. Presumably the anaesthetist preparing me for the operation diminished the flow of chloroform too soon, because I became conscious, without the least idea of where I was or what was happening: all I knew was that I was lying on my back, on a bed, with a stifling claw clamped down on my face. They had been lying! The monster had been there all the time and now it had come out and got me, I was dying! The dying felt like tipping over the edge of a cliff into black nothingness. I was hanging desperately on to the rim of the cliff. I was staring into that black nothingness – and horror of horrors, understood that it was not nothingness: there were shapes swimming about, things happening, creatures at large out there, and I was about to be pitched in among all that, unprepared, ignorant, totally incapable of coping. It was terrifying – surely one was supposed to change in some way at death, but I was still unchanged, still just my miserably inadequate self. Into my mind there came the thought, “If I start to believe in God perhaps I’ll be allowed to change so that I will know what to do?” At which – and I’m still proud of this – I answered myself: “No! That would be too shameful, just because I’m frightened.” I let go, and down into the black nothingness I slid.

So, when many years later I really was near death as a result of a haemorrhage after a miscarriage, and heard a doctor saying “She’s very near collapse – call the lab and tell him to run” and understood that the “him” was the person fetching the blood they were going to pump into me, I was not in the least alarmed as I dimly wondered if I had the strength left to think some suitable Last Thought, concluded that I hadn’t, and said to myself the words: “Oh well, if I die I die.” I was sure, then, that nothingness was just that.

I live now in an old people’s home with 42 others, our average age being 90, or perhaps a little more. When one makes the difficult decision (and difficult it is) to retire from normal life, get rid of one’s home and most of one’s possessions, and move into such a place (or be moved, which doesn’t apply here I am glad to say) it means that one has reached the stage of thinking, “How am I going to manage my increasing incompetence now that I’m so old? Who is going to look after me when I can no longer look after myself?” Death is no longer something in the distance, but might well be encountered any time now.

You might suppose that this would make it more alarming, but judging from what I now see around me, the opposite happens. Being within sight, it has become something for which one ought to prepare. One of the many things I like about my retirement home is the sensible practical attitude towards death that prevails here. You are asked without embarrassment whether you would rather die here or in a hospital, whether you want to be kept alive whatever happens, or would prefer a heart attack, for instance, to be allowed to take its course, and how you wish your body to be disposed of. Though when a death occurs in the home it is treated with the utmost respect, and also with a rather amazing tact in relation to us survivors, so that I doubt if anyone has ever been disturbed by such activity as I suppose surrounds the moment of a death, and the removal of a body: a carefulness of our peace of mind which must involve very well-planned management.

These matters have become discussable with one’s friends, not, of course, as a frequent part of gossip over lunch in the dining room (our only communal occasion) but from time to time, perhaps when admiring someone’s stoicism if their frailty is becoming painfully apparent, or feeling sad at someone else’s inability to accept what seems to be imminent. As a result of this openness, I think that most of the people here would consider it foolish to be frightened of being dead. All of us, however, feel some degree of anxiety about the process of dying.

That process depends on what you are dying of. The body can fail in ways that are extremely distressing, slowly and painfully, demanding much stoicism, or it can switch off with little more than a flash of dizziness. In my family we seem to have been uncommonly lucky in that respect. There was the 82-year-old uncle who was at a meet of the Norwich Stag Hounds, enjoying a drink with friends, when crash! And he fell off his horse, dead. There was the cousin in her eighties who fell dead as she was filling a kettle to make tea, and the other cousin, 98, who slipped away so gently that the sister who was holding her hand didn’t realise that she had stopped breathing. There was my mother, a week before her 96th birthday, who had one nasty day which, to my relief, she couldn’t remember the next morning, then slept her way out after speaking her last words, “It was absolutely divine,” about a recent drive to a beloved place. My father, alas, had a whole week of unhappiness after a blood-vessel in his brain had ruptured. He looked up as one came through the door, obviously about to greet one, then when he found he couldn’t speak, his expression became one of pain and puzzlement: he understood that something was badly amiss but he didn’t know what it was. The moment of his dying, however, was sudden and painless. My brother was the only person near me who clearly resented death, and that was because he had achieved a way of life which suited him so perfectly that he wanted more. He was not frightened of it. “No one after 80 has any right to complain about death,” he had said to me not long before.

That fortunate record makes me believe that although it would be unwise to expect an easy dying, it is not unreasonable to hope for one. As for after it, I feel quite strongly that I would like my ashes to be scattered or buried in a place I love (I scattered my mother’s in her garden – and the old man who tended it for her when she could no longer do it herself said “Cor! That won’t half make the flowers grow”). But such a feeling, though strong, is really absurd, because what does it matter to the dead how their bodies are disposed of? It is for the mourners to do what suits them best.

Alittle while ago I took part in a television programme about death that was designed by the photographer Rankin, to help him overcome his fear of it, to which he bravely admitted. Whether it served his purpose or not I don’t know – possibly not, because that fear is brewed in the guts, not in the mind – and I remember a man I once knew who suffered from it so badly that he told me he used to wake up in the night and have to telephone his sister and beg her to come round. “What did she do?” I asked, and he said she made tea and talked sense, but it didn’t do much good because the thought of all those bloody silly birds still twittering and those bastards walking up and down the street when he wasn’t there to see them drove him mad. But even if Rankin’s programme failed to make him feel better, which I hope was not the case, it was excellent, and many viewers responded to it with enthusiasm. I had already understood from the response to my own book, Somewhere Towards the End, that the taboo on the subject of death, so heavy in my youth, was evaporating, and this was a striking example of how true this is. Even teenagers joined willingly in discussion of it.

The contributor to the programme I remember with the most pleasure is the man who said that not existing for thousands and thousands of years before his birth had never worried him for a moment, so why should going back into non-existence at this death cause him dismay? Everyone laughed when he said that and so did I, and as I laughed I thought: “Dead right!”

THE LONG READ

No comments:

Post a Comment