|

| Photo by Thomas McDonald |

Trident: the British question

The debate is not simply about submarines and missiles. It touches almost every anxiety about the identity of the United Kingdom. The decision may tell us what kind of country – or countries – we will become

Thursday 11 February 2016

At this moment, a British submarine armed with nuclear missiles is somewhere at sea, ready to retaliate if the United Kingdom comes under nuclear assault from an enemy. The boat – which is how the Royal Navy likes to talk about submarines – is one of four in the Vanguard class: it might be Vengeance or Victorious or Vigilant but not Vanguard herself, which is presently docked in Devonport for a four-year-long refit. The Vanguards are defined as ballistic missile submarines or SSBNs, an initialism that means they are doubly nuclear. Powered by steam generated by nuclear reactors, they carry ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

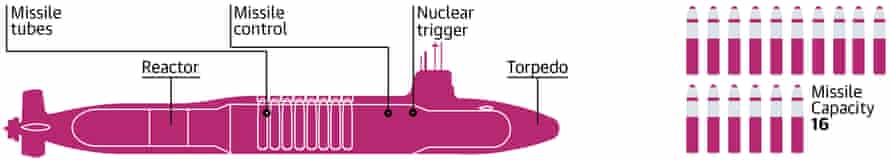

The location of the submarine – both as I write and you, the reader, read – is one of several unknowns. Somewhere in the North Atlantic or the Arctic would have been a reasonable guess when the Soviet Union was the enemy, but today nobody could be confident of naming even those large neighbourhoods. Another unknown is the number of missiles and warheads on board. Each submarine has the capacity to carry 16 missiles, each of them armed with as many as 12 independently targetable warheads; but those numbers started to shrink in the 1990s, and today’s upper limit is eight missiles and 40 warheads per submarine. Even so, those 40 warheads contain 266 times the destructive power of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

Vickers (now BAE Systems) built the submarine hulls at Barrow; Rolls-Royce made the reactors in Derby; the Atomic Weapons Establishment produces the warheads at Aldermaston and Burghfield in Berkshire. All these inputs are more or less British (less in the case of the Atomic Weapons Establishment, which is run by a consortium of two American companies and Serco), but the missile that they were built to serve and without which they would not exist is American: the Trident D5 or Trident II, also deployed by the US navy, comes out of the Lockheed Martin Space Systems factory in Sunnyvale, California.

According to the Ministry of Defence, a British ballistic missile submarine has been patrolling the oceans prepared to do its worst at every minute of every day since 14 June 1969, when the responsibility for Britain’s strategic nuclear weapons passed from the Royal Air Force to the Royal Navy. Over the course of 46 years, many things have changed. Resolution-class submarines with Polaris missiles were replaced with Vanguards and Tridents nearly 20 years ago. The submarines are far bigger – a Vanguard submarine is twice as long as a jumbo jet – while the missiles have enormously increased their range and the warheads their precision. But the system, known as continuous-at-sea-deterrence or CASD, is essentially the same: four submarines work a rota which has one submarine on a three-month-long patrol, another undergoing refit or repair, a third on exercises, and a fourth preparing to relieve the first. The navy’s code name is Operation Relentless.

This is an epic vigil, born in the cold war and not abandoned by its passing, and the government intends that it continues into a third generation of ballistic missile submarines – the provisionally-named Successor class – that will work to the same pattern as the Vanguards and carry a new version of the Trident D5, now under development. In the end, a military strategy devised to deter attack by the Soviet Union will have outlived its original enemy by at least half a century.

Since the advent of the industrial revolution, few weapons systems have survived so long. The modern battleship, devised under the empty blue skies of Edwardian Britain, demonstrated its vulnerability to air attack even before Pearl Harbor; its useful career lasted hardly 40 years. Britain’s submarine-launched nuclear weapon, on the other hand, seems immune to obsolescence – as well as to financial, social and political hazards such as reductions in public spending, deindustrialisation, and the growing possibility of the break-up of the kingdom it was designed to protect.

2. ‘This project is a monster’

The Scottish Question is a familiar one. But Trident sits at the heart of a more complicated puzzle – what we might call the British Question – and embodies many of the crises and anxieties that have afflicted the United Kingdom since the second world war: the passing of empire, the “special relationship” with the United States, the decline of manufacturing and the disappearance of an industrial working class (and its consequences for the Labour party) – and, of course, the spectre of Scottish independence and the end of a United Kingdom. Trident and its ancestors have been among the causes and consequences of all of them. Where and how (if at all) its successors are deployed will be a measure of the kind of country, or countries, that Britain becomes.

The Strategic Defence and Security Review that was presented to parliament last November described the building of the four Successor submarines as “a national endeavour … one of the largest government investment programmes, equivalent in scale to Crossrail or High Speed 2”. It will “require sustained long-term effort”, the report added, along with radical organisational and managerial changes to “create a world-class, enduring submarine enterprise”. The boosterism that inflects this language may reveal rather than disguise an underlying nervousness: the more a British government talks of “world-class” schemes and institutions, the faster we should count the spoons.

Crossrail and HS2 are Britain’s most expensive public infrastructure projects (with the possible exception of the Hinkley Point nuclear power station, whose eventual cost to the public purse is hard to quantify). Recent estimates put the cost of Crossrail at £15.9bn and the first leg of HS2 – the 120 miles between London and Birmingham – at £30bn. The defence review increased the estimated manufacturing cost of the four Successor submarines to £31bn from an estimated £25bn that had held good from five years before, and for the first time added a contingency estimate of another £10bn.

Delivery of the new fleet, already delayed from the early 2020s to 2028, is now scheduled to begin in the early 2030s, postponing the withdrawal of Vanguard submarines at least 10 years beyond their expected operational life. According to the defence review, the increased cost and delayed schedule “reflect the greater understanding we now have about the detailed design of the submarines and their manufacture”. Beyond this opaque statement, the Ministry of Defence will not explain why the cost should have risen by nearly a quarter during five years of near-to-zero inflation, for a programme that was authorised (by Tony Blair’s government) as long ago as December 2006 and which has already cost £3.9bn in its so‑called design phase. And this is only the beginning of mountainous public expense.

Until last autumn, the generally accepted figure for the price of the entire Successor programme – and the one used by its critics, such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – was £100bn. This is the cost of building and then arming, running and repairing four nuclear submarines over 40 years of operational life, followed by their upkeep as decommissioned hulks until the navy decides how to dispose of them. (A safe way of scrapping a nuclear submarine has still to be found; the 19 that the Royal Navy has so far withdrawn from service – the oldest of them in the 1980s – are all still laid up in navy dockyards at Rosyth and Devonport.)

But in October, the Tory MP Crispin Blunt, a Trident sceptic, used information contained in a parliamentary reply from a junior defence minister, Philip Dunne, to estimate a far higher figure. Dunne had said that the in-service cost of the Successor programme would be about 6% of the annual defence budget over the project’s lifetime. Nobody, of course, can know what the UK’s defence budget will be in 20 years’ time; Blunt’s calculations presumed that it would not fall below 2% of GDP, which is the present government’s promise, and that GDP would grow at the rate expected by the government and the International Monetary Fund. On that basis, and on the assumption that in-service costs would run from 2028 to 2060, Blunt concluded that Successor would cost £167bn – a price, he said, that would consume double its predecessor’s proportion of the defence budget and was now “too high to be rational or sensible”.

It may turn out to be lower. The new submarines may not last so long in service as the 32 years assumed by Blunt, and the principle of continuous-at-sea-deterrence could be modified – continuous only at times of international tension, for example – or even abolished by a future government. On the other hand, the cost could be higher. Dunne’s figure for the submarines’ building costs – £25bn – was raised by at least £6bn only a month later. Appearing in October before parliament’s public accounts committee, the senior civil servant at the Ministry of Defence, Jon Thompson, could only say that it was “extremely difficult” to estimate future costs – calling it “the project that most keeps me awake at night” and “a monster”. Stewart Hosie, the Scottish National party’s deputy leader at Westminster, said it was “truly an unthinkable and indefensible sum of money to spend on the renewal of an unwanted and unusable nuclear weapons system”.

After independence itself, the SNP’s best-known political aim is the ejection of the UK’s nuclear-missile fleet from its base at Faslane on the Clyde. Over the next 15 years, a second referendum on the independence question in which Scotland votes to leave the United Kingdom is at least a strong possibility. The SNP, should it form the first independent Scottish government, would no doubt be pragmatic and opportunistic in its negotiations with London, but it seems unlikely that Faslane would continue as the home of another state’s nuclear deterrent. Its place in the SNP’s rhetoric has become far too prominent for that kind of compromise, even if London wants it.

So far all the Ministry of Defence will say is that there are no plans to move the nuclear deterrent from the Clyde and that “any alternative solution would come at huge and unnecessary cost”. But unless the Trident renewal programme is something that the government secretly wants to cancel and would be happy to see sunk by Scottish independence, plans must exist to move the base out of Scotland. “Huge and unnecessary cost” – so far unspecified but certain to be several billion – is therefore what the UK-minus-Scotland will face.

3. The landscape of the cold war

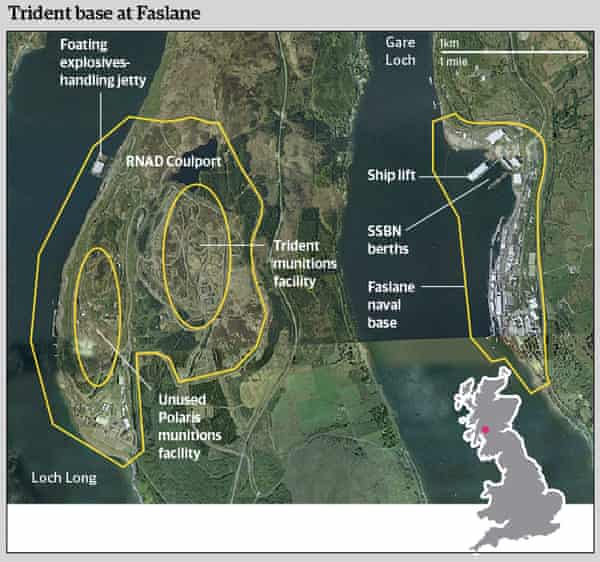

Faslane, officially Her Majesty’s Naval Base Clyde, is one of the most unexpected sights in modern Britain. The visitor imagines a small dockyard disfiguring a bare Scottish coast. What he finds instead is a long settlement that stretches for nearly two miles down the eastern shore of the Gareloch, the gentlest and most suburban of the Clyde’s seven larger sea lochs, an hour’s journey from Glasgow by commuter train and local bus.

The best view of the base is from the loch’s western side, where a scattering of seaside villas, built in Victorian times for the Glasgow gentry, stand back from the little road that leads south down the Rosneath peninsula towards the open firth. A wood separates the road from the loch, but here and there a rough path leads down to a rocky beach glistening with damp seaweed. Scramble down one of these paths and you look across a mile of calm water to the kind of industrial scene that has vanished from most of Britain. Among the wharves, cranes, ships and sheds, a tall chimney marks the power plant that can generate enough electricity for a town of 25,000 people. Nearby, a ship lift capable of holding a 16,000-tonne submarine rises to the height of an 11-storey building. A cluster of accommodation blocks looks as trim and permanent as a fair-sized municipal housing estate. Faslane has a hospital, shops, naval mess rooms and civilian canteens.

No other industrial site in Scotland has as many workers: Faslane employs about 6,500, while another 200 work over the hill on Loch Long at the armaments depot at Coulport, where the missiles are “mated” with their warheads. By day, the scene on the Gareloch is full of movement. Police launches and small grey warships come and go from the jetties, and sometimes, assisted by tugs, the heavy, dark shape of a submarine moves into mid-channel and slides towards the Firth of Clyde. By night, from the straight hill road that was built to take the lorries loaded with nuclear warheads on the last leg of their journey from Berkshire to Coulport, the base spreads out below like a brightly lit seaside resort with a pier and a promenade. Security is dramatically visible: double razor-wire fences, sentry posts, watch towers. Sometimes, driving slowly to take in the view, you form the impression that the car behind is also taking an interest – when you stop, it stops – too artfully, you think, but then you were raised on the paranoid fictions of the cold war.

Faslane belongs to that time, and more particularly to one of its most influential theories: that the immensely destructive power of nuclear weapons had changed the purpose of military strategy from winning conflicts to deterring them. An adversary would be dissuaded from attacking because the lives and property lost in a counter-attack would be too heavy a price to bear. No matter the difference in military strength between the powers – for example, between the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom – the same calculation would still apply. It wouldn’t quite be tit for tat. The Soviets could easily wipe out the UK completely and capture what remained of its resources, while UK retaliation might amount only to the ruination of Moscow. But for the Soviet Union, that might be dissuasive enough.

The weakness in the theory was the surprise attack, in which the aggressor state struck at military installations to eliminate its victim’s capacity to hit back. How was that capacity to be kept intact? Defensive missile shields offered only limited protection to pre-emptive attacks on the static (and hardly secret) locations of land-based nuclear weapons: airfields for the aircraft that would drop free-fall bombs and the silos that sheltered intercontinental ballistic missiles. Submarine-based weapons, on the other hand, had the twin advantages of mobility and near-invisibility. A new method of propulsion, in which a nuclear reactor made the steam that drove the turbines, was a sealed system that, unlike the diesel engine, neither needed air nor emitted waste; human endurance was now the main limitation to the length of a submarine’s voyage. A nuclear submarine could travel as fast as any large surface ship and at lower speeds much more quietly, and therefore less detectably, than its diesel-driven predecessor. The increasing range of missiles meant that by the early 1960s they could be fired well out to sea and hit a target a thousand miles inland. Their submarine launch platform had a whole ocean to hide in.

The US navy commissioned the world’s first nuclear submarine, the Nautilus, in 1955. On his visit to Britain the next year, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev told an audience at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, that a future war would not be “decided by cruisers, not even by bombers. They too are outdated … Today the submarine fleet has come to the forefront as the chief naval weapon, and the chief aerial weapon is the missile, which can hit targets at great distances, and in future the distance will be unlimited.”

By 1957, this had become equally clear to the Royal Navy. In the words of an Admiralty paper published that year, if Britain didn’t acquire nuclear submarines it would “cease to count as a naval force in world affairs”. The first of them, HMS Dreadnought, put to sea in 1962, but only after considerable technical assistance from the US navy and the American engineering company Westinghouse. It marked the beginning of a dependence on American technology that has grown with every generation of British missile submarines since.

4. Losing an empire

I saw Faslane for the first time in the early summer of 1958, from a steam train puffing slowly into the western Highlands. I remember a bay scattered with small craft at anchor and a glimpse of one of Britain’s last battleships, which was being dismantled at the breaker’s yard that in those days occupied the bay. Later research shows that the battleship must have been HMS Anson – named after Admiral George Anson, who defeated the French at the first battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747. At the time I recognised her only as a member of the King George V class: ten 14-inch guns in three turrets, two funnels, 27 knots at full speed.

I knew this because I lived next door to a royal dockyard, Rosyth, and ships had become an enthusiasm. I liked their taxonomy – destroyers, frigates, minelayers, corvettes – and easily absorbed the details of their fighting power from books with titles like The Boys’ Book of the Navy. There was, of course, something else – some ineffable boyhood veneration of the ship itself and with it the kind of patriotism – unexamined, omnipresent – that came from watching films about the war at sea. I argued with an American boy at my primary school. Who had the bigger navy? I contested, insupportably by then, that it was ours.

The 1950s were what the journalist Nigel Fountain once described as Britain’s “Icarus period”. It still imagined itself as the world’s third great power, equipped industrially to pioneer exciting and, as it turned out, risky technologies such as jet airliners and nuclear power stations. British innovation allowed a different kind of patriotism – scientific achievement rather than imperial dominion – but many of its pet projects fell to earth (the world’s first jet airliner, the Comet, did so literally and too often), while others failed to take off. This was the case with the Blue Streak medium-range ballistic missile, which the government intended as the successor to an RAF bomber fleet that improved Soviet air defences were making obsolete. For a time, the Blue Streak symbolised Britain’s bright future (I remember Blue Streak racing bikes for boys and Blue Streak bubble gum), but it was eventually cancelled on the grounds that land-based missiles were vulnerable to a pre-emptive strike.

Britain then turned to an air-launched ballistic missile, the Skybolt, which America was close to putting into production, but in 1962 that too was cancelled after a series of test failures. This was a grave blow to British plans – an agreement reached between President Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had made the deal for the Skybolt look a certainty. If Britain was to persist with an effective nuclear deterrent, it needed to persuade the US to let it have the only available alternative: the powerful submarine-launched missile, Polaris.

Britain had some leverage here: in 1961 the US navy had established a forward base for its Polaris fleet at the Holy Loch, which lies only seven or eight miles across the Clyde from the Gareloch. During the negotiations over the site, the British side raised the idea that one day Britain might obtain Polaris missiles for itself. The Americans resisted the idea; they distrusted British behaviour after the Suez invasion five years earlier and, more broadly, believed that the fewer countries that possessed their formidable new weapon the better. Enmities developed. There were rumours that Washington wanted to push the UK out of the nuclear business.

It was in this context – and only a fortnight before Macmillan met the US president, John Kennedy, at a specially convened summit in Nassau in December, 1962 – that Kennedy’s foreign policy adviser, Dean Acheson, delivered a speech at the West Point military academy. “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role,” he said in the speech’s most celebrated passage. “The attempt to play a separate power role … apart from Europe, a role based on a ‘special relationship’ with the United States, a role based on being head of a ‘commonwealth’ which has no political structure, or unity, or strength – this role is about played out.”

The speech infuriated Macmillan – Acheson, he said, had made the same mistake as “quite a lot of people in the last 400 years, including … Napoleon, the Kaiser and Hitler” – and the discussions with Kennedy in the Bahamas became, in his words, “protracted and fiercely contested”. America insisted that it would sell Polaris to Britain only if control of the missile was assigned to Nato, but that wasn’t Macmillan’s idea of an independent deterrent. Finally, the two sides brokered a compromise that gave control to Nato but reserved Britain’s right to act independently – that is, to fire the missile without consulting anyone else, including the US – in situations where “Her Majesty’s Government may decide that supreme national interests are at stake”. With these dozen words, Britain could claim that its new deterrent would be free from foreign veto over its use. The warheads and the submarines would be made in Britain. Polaris was certainly an American missile, made by Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin) in California, but it would be just as obedient to British command as the British-built bombers it replaced.

The Nassau agreement laid down the fundamentals of the military policy that the UK has followed ever since, but as Peter Hennessy and James Jinks write in their fine history of the Royal Navy’s submarine service, The Silent Deep, the agreement’s attempt “to reconcile interdependence with independence remained a source of continuing difficulties … as the two countries disagreed over what exactly had been agreed”. Kennedy’s under-secretary of state, George Ball, described it later as “intolerably vague” and a “monument of contrived ambiguity”.

Nobody could say for sure what fell into the category of “supreme national interests”; most people, including Kennedy, found it hard to imagine Britain launching an atomic warhead without American assent. Solly Zuckerman, the UK government’s chief scientific adviser, decided that the question “How independent?” was as pointless as medieval disputation. If Polaris missiles ever came to be fired, the British public “would never even know” whether they had reached their target. “There would be no newspapers to tell us, no television … and maybe no ‘us’, just the crews of those Polaris boats that had been at sea.”

5. How Trident reached Faslane

We are often traitors to our earlier selves. In 1958, I was the kind of boy who loved warships; in 1961, I was another kind of boy who opposed them. The US navy established its Polaris base in the Holy Loch that year (it stayed until 1992) in the face of fierce opposition from the anti-nuclear movement, which was reaching its first peak. Ongoing atmospheric testing, the effects of radiation on Japanese fishermen, the better-dead-than-red rhetoric of politicians, the obvious futility of civil defence: all contributed to the general foreboding and, among a minority, the need to protest.

Civil disobedience and non-violent resistance, then novel techniques to Britain, gave the demonstrations unprecedented publicity. The Holy Loch protest that I joined on a September afternoon in 1961 had its farcical dimension; a gale prevented our ferry from landing its cargo of several hundred protesters, sending us back across the Clyde to march miles away from the base. Nevertheless, more than 350 people did manage to get arrested at a sit-in at the base’s gates, where American sailors making their entrances and exits were taunted and teased with chants of “Yankees go home!” and “Ye canny spend a dollar when ye’re deid” (to the tune of “She’ll be coming ’round the mountain”). The anti-nuclear cause in Scotland had a distinct and memorable flavour, less solemn than the protests in the south – the songs had a Glasgow swagger and wit – but also more xenophobic, because the nuclear weapons being protested against weren’t even our own.

There was another difference, which in terms of Scottish political attitudes may be the Holy Loch’s most important legacy: one of the most beautiful seascapes in Europe – of longstanding aesthetic and recreational value to industrial Scotland – had been chosen by the United States as the site for a nuclear base with the connivance of a British government. It was hard to resist the conclusion that the British government worried more about preserving the safety and landscape of southern England than it did about those things in western Scotland. The SNP at the time was insignificant as a political influence, but its opposition to Polaris at its 1961 conference, extended to all nuclear weapons two years later, began to rouse a slumbering grievance.

In fact, it was Washington’s brute power rather than London’s duplicity that decided the location. According to the military analysts Malcolm Chalmers and William Walker (writing in their 2001 book, Uncharted Waters), the Americans wanted a sheltered anchorage with access to deep water that was situated “near a transatlantic airfield and a centre of population in which the American service personnel could be absorbed”. The Holy Loch was an obvious choice; it was close to Prestwick airport and the bright lights of Glasgow, sheltered from the prevailing south-westerlies, and stood a better chance than a more open location of confining a nuclear spillage, should one occur.

A deal between the Admiralty and the US navy was close to being agreed when Harold Macmillan intervened and asked the two sides to think again. He was alarmed at the prospect of nuclear weapons being based 30 miles from Glasgow and its “large number of agitators”; in a letter to Eisenhower, Macmillan noted that its status as a Soviet target “would give rise to the greatest political difficulties and would make the project almost unsaleable in this country”.

The Admiralty looked again at the possibilities and this time included Falmouth in Cornwall, Milford Haven in west Wales, and Fort William in the western Highlands, the last favoured by the Macmillan’s cabinet because of its distance from large populations. But the US navy was adamant in its choice and the political difficulties foreseen by Macmillan duly arrived, in terms of the Holy Loch protests. But these didn’t last long – the end of atmospheric testing and the peaceful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis had drawn the sting from the nuclear disarmament campaign.

As a result, the question of where Britain’s own Polaris submarines were to be based aroused remarkably little attention when the government began its deliberations in 1963. Many of the criteria were the same as the Americans had applied earlier. The Admiralty wanted a base near deep water that had easy access to a labour force and could be easily supplied by road and rail – and in addition, for safety reasons, a missile storage and loading site that was separated by at least 4,400ft from the regular docking berth, where routine maintenance was carried out and crews came and went. These requirements ruled out all islands, the remote north-west of Scotland, and the south and east coasts all the way from Dorset to Berwickshire, just below the Firth of Forth. Of the eventual longlist of 10, Milford Haven was judged too close to an oil refinery; Invergordon and Loch Alsh were too remote and too vulnerable to submarine attack; Devonport had the city of Plymouth on its doorstep. Falmouth was perfect in every way, but the land there owned by the Duchy of Cornwall and the National Trust was held to be too expensive and difficult to buy, and the government working party felt that “a strong case would be required to justify spoiling a national beauty spot or vigorous sailing centre”.

That left two Scottish sites. The Treasury and the ministries of defence and transport favoured Rosyth in the Firth of Forth, mainly because it was cheaper: it had a spacious dockyard with a separate munitions jetty already in place. (The fact that Edinburgh’s 450,000 people lived only 10 miles away apparently played no part in the argument for or against.) For operational reasons, the Admiralty much preferred Faslane: its site in the Gareloch offered better shelter and protection than Rosyth, and the Clyde’s geography gave a submerged submarine a choice of deep-water routes towards the Atlantic. The firth was also particularly well equipped as a submarine testing ground. Its long sea lochs held deep, calm water, notably free of inconvenient shoals and rocks, which the Royal Navy had used from the start of the 20th century as the test-bed for the products of its Greenock torpedo factory. During the second world war, when the Clyde became a primary destination for transatlantic shipments of troops and supplies, Faslane Bay had acquired a substantial harbour, a railway connection and a title: Military Port Number One. Postwar, half of it was given over to shipbreaking and the other half to a flotilla of pre-nuclear submarines.

These convenient legacies of older wars clinched the navy’s case for Faslane as the base for Polaris. By 1968, work had finished on new docking facilities in the Gareloch and the loading jetty and missile bunkers at Coulport, and the Admiralty could congratulate itself on one of the largest building projects it had ever undertaken. Much bigger things were to come. Twelve years later, when the governments of Britain and the United States agreed to replace the Polaris system with the Trident D5, an extravagant programme of works made Faslane into the largest building project in Europe – one never equalled before or since in the history of the Ministry of Defence. The ship lift, the power station, the new road to carry warheads that was bulldozed nine miles down the glen: by 1994, thanks partly to the more stringent safety standards that followed the Chernobyl disaster, the reshaping of Faslane had cost £1.9bn (£3.5bn at today’s prices) and was 72% over budget. The ship lift can withstand earthquakes up to 8 on the Richter scale.

I’ve travelled around this part of Argyllshire often enough, and seen it, too, from boats and steamers on the Clyde. There is melancholy here. The industrial prosperity that created its marine villas and yacht slipways began to ebb away after the first world war; by 1952, the writer George Blake could describe the settlements around the Gareloch and Loch Long as “slightly pathetic backwaters” – which in the case of Coulport’s long range of seaside houses “wore the look of something that had not quite come off and had been written off”. In 2005, when the Ministry of Defence demolished the last of these Victorian houses, the original Coulport vanished. Other and grander dwellings went long before: Rosneath Castle, home to Queen Victoria’s daughter Louise, the Duchess of Argyll; Shandon House, built for the innovative shipbuilder and cofounder of the Cunard Line, Robert Napier. Country retreats had been buried under an armed advance.

One bright afternoon last autumn as I drove along the miles of boundary fence, it struck me that this might be the last great military landscape that the United Kingdom would create, the last chapter in a history that includes the Grand Fleet’s anchorage at Scapa Flow, the artillery ranges of the Salisbury Plain and the bomber airfields of Lincolnshire. Would there ever be the money again? Or the will or the need? Once all these things had seemed like scars on the land: the new straight roads, the roundabouts, the street lights, the watchtowers, the ship lift, the anonymous sheds that held God knows what. Now it was interesting to see them as potential ruins, something an empire left behind in the hills as it abandoned the frontier and shrank back to the capital.

6. Everybody’s headache

On 3 September 1986, Margaret Thatcher laid the keel of the first Trident submarine, HMS Vanguard, at Vickers’ shipyard in Barrow. Earlier that year, the most eloquent case for its cancellation had been made by the first episode of Yes, Prime Minister, the BBC comedy series written by Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn in which a fictional prime minister, Jim Hacker, is in perpetual battle with his most senior civil servant, Sir Humphrey Appleby. “I’ve decided to cancel Trident,” Hacker tells an astonished Sir Humphrey. He intends to divert some of the savings into conventional forces and reintroduce conscription, and “at one stroke” solve Britain’s balance of payments, educational and unemployment problems.

Sir Humphrey [scandalised] : With Trident we could obliterate the whole of eastern Europe.

Hacker: I don’t want to obliterate the whole of eastern Europe.

Sir Humphrey: But it’s a deterrent.

Hacker: It’s a bluff. I probably wouldn’t use it.

Sir Humphrey: Yes, but they don’t know that you probably wouldn’t.

Hacker: They probably do.

Sir Humphrey: Yes, they probably know that you probably wouldn’t. But they can’t certainly know.

Hacker: They probably certainly know that I probably wouldn’t.

Sir Humphrey: Yes, but even though they probably certainly know that you probably wouldn’t, they don’t certainly know that, although you probably wouldn’t, there is no probability that you certainly would.

Hacker: What?

This wizard-behind-the-curtain aspect of Trident is the official reason for having it. What matters is belief. The navy could fill the sharp end of a Trident missile with straw, but if the straw could be kept a perfect secret and the world went on believing that instead of straw there were warheads capable of destroying 266 cities, each the size of Hiroshima, then Trident would be doing its job. If it had to be used, then the world, or what was left of it, would of course discover the truth. But if it had to be used, it wouldn’t have worked (and there would be few of us left to care).

When Jeremy Corbyn said in September that he was opposed to the use of nuclear weapons – though his refusal to “press the button” was never stated in so many words – General Sir Nicholas Houghton, chief of the defence staff, responded by saying that a prime minister who announced he would never fire nuclear weapons “completely undermined” the deterrent. In theory, this is true. Provided the enemy was credulous as well as rash, this disavowal of nuclear retaliation might make an adversary more ready to attack. (A more cautious enemy might decide that all such a prime minister’s statement probably meant was that he probably wouldn’t.) But Houghton’s argument that the UK uses the deterrent “every second of every minute of every day” invites greater scepticism. Just exactly what has been deterred? And why have non-nuclear weapons states such as Germany, Spain and Japan been just as successful in deterring it?

Even before it possessed them, Britain’s need for nuclear weapons was contentious. “We’ve got to have this thing [the atom bomb] over here whatever it costs [and] we’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it,” were the words of the Labour foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, in 1946 after he returned from an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Washington to share its nuclear expertise. Not everyone in government was convinced. The small cabinet committee that met a few months later to sanction Britain’s nuclear programme was careful to exclude ministers such as the chancellor of the exchequer who might object on grounds of cost, and the military also had doubts. A memo from Sir Henry Tizard, the chief scientific adviser to the ministry of defence, suggested that Britain’s pursuit of the bomb made the country blind to reality. “We persist in regarding ourselves as a great power capable of everything and only temporarily handicapped by economic difficulties. We are not a great power, and never will be again,” Tizard wrote in 1949, adding: “We are a great nation, but if we continue to behave like a great power we shall soon cease to be a great nation.”

The question has divided Britain, and particularly the Labour party, more than any other other nuclear weapons state. In France, which has a similar nuclear strategy, the left was happy to applaud the force de dissuasion, but Labour’s Christian and anti-war traditions made it more difficult for the leadership to celebrate military power, at least openly. On the other hand, it needed to be seen as patriotic. In the words of Professor Michael Clarke, formerly of the Royal United Services Institute, support for nuclear weapons came to stand “for the defence of the realm in general”. What Clarke calls “the prevailing party folklore” – that embracing unilateral nuclear disarmament had cost Labour the 1983 election – turned it into a party that, at least until Corbyn became its leader, had to be more loyal than the king.

In their history of the Royal Navy’s submarine service, Peter Hennessy and James Jinks describe this troubled history as “Labour’s nuclear neuralgia”. What its leaders wanted was often difficult to know. The manifesto for the 1964 election said that the Nassau agreement to buy Polaris nuclear missiles from the US would “add nothing to the deterrent strength of the Western Alliance … [Polaris] will not be independent and it will not be British and it will not deter … We are not prepared any longer to waste the country’s resources on endless duplication of strategic nuclear weapons.” Nothing could be plainer. The military establishment, including the then chief of defence staff, Lord Mountbatten, firmly believed that Polaris would be cancelled if Labour won; the government encouraged the Admiralty to spend as much as possible on the submarine programme to make cancellation more difficult. But Labour’s victory, when it came, changed very little apart from shrinking the intended Polaris fleet from five submarines to four.

Harold Wilson, the new prime minister, was told that the construction of the first two submarines “had passed the point of no return” and seemed anxious to believe it. As he later admitted, the deterrent “had an emotional appeal to the man in the pub”, omitting to say that this might not be the case for the man in the party. When the first of the Polaris submarines, HMS Resolution, was commissioned into the navy in 1967, no representative of Wilson’s government attended the ceremony. In his memoirs, the chief executive of the Polaris programme, vice-admiral Sir Hugh Mackenzie, recalled that while Labour ministers were happy to give “their support wholeheartedly, and even enthusiastically” to Polaris in private, in public they “remained sensitive to anything to do with it … and were reluctant to encourage much in the way of publicity for what it was achieving.”

In its manifesto for the 1974 election, Labour promised that when Polaris expired in the early 1990s it would not be replaced with a new generation of nuclear weapons – a policy similar to the non-renewal of Trident that Jeremy Corbyn now wants Labour to adopt. The party’s next election manifesto, in 1979, was more cautious, stressing that “a full and informed debate” was needed before a Labour government made such radical commitment, but even so it still believed that non-renewal was “the best course for Britain”.

This impression of open-mindedness was misleading. Since 1977, a small group of Labour ministers and government officials, known as the Restricted Group, had been meeting secretly to discuss how the nuclear deterrent might be continued when Polaris reached the end of its life in the 1990s. Two senior civil servants, Sir Anthony Duff and Sir Ronald Mason, were commissioned to write a study: the result is a key document in British military history, the Duff-Mason report, which in its three parts laid out the pros and cons of renewing an independent nuclear deterrent, the criteria such a deterrent would need to meet to be effective, and the weapons systems that might deliver it. What level of damage would the Soviet Union consider to be unacceptable? The report suggested that it might be reached by “the disruption of the main government organs of the Soviet State [in Moscow] or by causing grave damage to a number of major cities involving destruction of buildings, heavy loss of life, general disruption and serious consequences for industrial and other assets.” Moscow’s anti-ballistic missile defences and underground bunkers narrowed the chances of a successful attack; the other options included “breakdown level damage to Leningrad and about nine other major cities” and “grave damage, not necessarily to breakdown level, to 30 major targets, including Leningrad and other large cities”.

Ministers and officials in the Restricted Group read the Duff-Mason report in December 1978 and made various suggestions about how cheaply “unacceptable damage” in any of its forms might be delivered. David Owen, the foreign secretary, wanted to adapt ordinary attack submarines (known as SSNs) so that they could launch shorter-range cruise missiles carrying nuclear warheads. Someone else proposed collaborating with France, which by now had its own fleet of ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). Michael Quinlan, a deputy under-secretary of state at the Ministry of Defence, thought that a casualty figure of up to 10 million Soviet dead might not be enough to deter a country that had lost more than 20 million people in the second world war. “In this field nothing is provable,” Quinlan wrote, “but it is far from clear that they would regard less than half of 1% of their population as an unthinkable price for contemplating a conquest of western Europe.”

Of the options available, James Callaghan, Wilson’s successor as prime minister, echoed the recommendation implied in the Duff-Mason report and favoured the Trident missile system that was then being developed for the US navy. The next month – January 1979 – he flew to a summit meeting between the UK, the US, France and Germany held in Guadeloupe, where he intended to have a private session with the US president, Jimmy Carter. It was on his return from this summit that his nonchalant response to a reporter’s question about Britain’s social turmoil that winter became the headline, “Crisis? What crisis?” – famous words that were never in fact spoken by Callaghan but helped lose him the general election. What he returned with might be said to be far more consequential – an assurance from Carter that the UK could have Trident if it wanted it; information that, together with the Duff-Mason report, he passed to the incoming government of Margaret Thatcher, who immediately became embroiled in the arguments over its cost.

Nuclear neuralgia has never been confined to the Labour party. The need to have as cheap a deterrent as possible has been the source of conflict within governments since the early 1960s, asserting itself most obviously with the question: how many submarines do we really need? First raised with the Polaris, this question returned with Trident and returned again with Trident renewal, and each time, after pressure from the Ministry of Defence, the eventual answer has been a quartet. In 1980 as in 1964, the Royal Navy wanted five, though some members of Thatcher’s government wanted none at all. John Nott, the defence minister charged with pressing Trident’s case, reported to Thatcher in February 1981 that two-thirds of the Conservative party and two-thirds of the cabinet opposed the purchase of Trident and that even the chiefs of the defence staff were not unanimous. Nonetheless, three submarines were sanctioned in January 1982, with a fourth added only a few months later.

The building programme had financial repercussions that went far beyond the cost of the vessels themselves and their remodelled base at Faslane. At Barrow, the Devonshire Dock Hall, the largest indoor shipyard in Europe, was built specifically to handle their construction. At Aldermaston, new facilities were needed to produce the Trident warheads. Even so, Nott could boast in 1982 that Trident’s cost over 15 years would be about 3% of the UK’s annual defence budget – compared to the 20% of annual defence spending that an independent deterrent was costing the French. Whereas the Polaris missiles had to be removed from submarines for routine maintenance and a change of warhead, the design of the Tridents made that unnecessary: repairs could be done, and the warheads changed, without offloading the missiles. That made a lot of Coulport’s work redundant. On the far fewer occasions that a missile had to leave or join the ship, the US Navy proposed that the operation could be carried out at its base in the state of Georgia – reducing Trident’s costs, at the cost of compromising the idea of its independence. A meeting to consider the proposed new arrangements decided, in the words of Thatcher’s summing-up, that “the political and financial advantages of carrying out missile processing in the United States outweighed the marginal reduction in the independence of the Trident system and the eventual loss of job opportunities in Scotland”. The unspoken reality, then and since, is that the US could eventually disable Britain’s nuclear deterrent if it chose to by cutting off technical help and equipment – it might take months, but the outcome would be certain.

That hardly mattered in a strategy where perception was everything and Britain and the US had a common enemy. According to the record of the decisive meeting, Thatcher had been persuaded to up the number of submarines from three to four because three would not be a credible deterrent “so far as the perception of the Soviet Union was concerned”. Nobody conceived any other adversary.

The Duff-Mason report had been quite explicit: “Over the next 30-40 years, our planning need not be geared to any nuclear threat beyond the Soviet Union.” And yet on 26 December 1991, little more than 13 years after that sentence was written, the Soviet Union voted itself out of existence. In 1994, the British government announced that Moscow, Leningrad (St Petersburg) and other sites in the former Soviet Union had been dropped as targets, and that Trident’s guidance computers no longer routinely held targeting information – implying that the coordinates of new targets would be programmed if and when they were identified. When the first of the Trident fleet, HMS Vanguard, put to sea, the Soviet Union had been dead two years. By the time the fourth submarine, HMS Vengeance, began its operational life in November 1999, it had been gone for the best part of a decade. The four most expensive ships ever built for the Royal Navy had arrived too late for the party.

7. Not just another country

One morning last October, I had coffee with Feargal Dalton, a former lieutenant commander of a Trident-missile submarine. We met by arrangement in the house of a friend who lives a mile or two down the coast from the warhead jetty at Coulport. From this house, a bungalow set high on a hill, you look down on the great broad junction of the Clyde, where sea lochs join the estuary from the north and west, and the estuary takes a 90-degree turn towards the south and the Atlantic. It was a still morning of mist and sun. The sea was silvery, and creased only by the wakes of small warships on a naval exercise.

This was familiar territory to Dalton, who spent 15 of his 17 years in the Royal Navy in submarines, eventually as a weapons engineering officer, a WEO, in charge of the missiles. In fact, he is one of the few Royal Navy officers – he believed there were “only nine or 10 of us” – to have pulled the trigger and sent a Trident D5 bursting out of its undersea compartment and roaring into the air towards its target on the US’s test range off the coast of Florida. The missiles cost about $37m (£26m) each, so firings are rare. Dalton got his chance in May 2009 when his submarine, HMS Victorious, underwent what is known as a Daso, a Demonstration and Shakedown Operation, after a substantial refit. These firings are usually publicised. As Hennessy and Jinks write: “Central to remaining a nuclear-weapons nation is the need at regular intervals to show the rest of the world that is exactly what the UK still is.” But Dalton’s event was completely ignored by the media. “Check it,” he said. “It just didn’t happen. Gordon Brown didn’t want the media to notice because a non-proliferation meeting was being held around the same time.”

He seemed irritated by this – in his view, it was typical of Labour’s muddled and hypocritical attitude towards nuclear weapons. You had to stand up and be counted for or against them, and now he was against them, having left the navy in 2010 to become a teacher and an SNP councillor in Glasgow. (His wife, Carol Monaghan, is one of the city’s new SNP MPs.) Everything about Dalton is unlikely. His family’s political history is in the militant Irish Republicanism of South Armagh; nonetheless, he said it was the IRA atrocities at Enniskillen and Warrington that persuaded him to join the Royal Navy after he graduated with an electronics degree from University College Dublin. He wore a few badges in his lapel: an enamel Armistice poppy, a veteran’s pin, the insignia of the submarine base HMS Neptune. He said several times that it was to the Royal Navy’s “immense credit” that it had accepted and promoted him despite his background. He loved the Royal Navy and at the same time wanted Scotland to kick it out. He hated nuclear weapons and at the same insisted that he would have fired one for real if he had been ordered to.

We drank our coffee. Dalton said that submarine crews were just as sceptical about the independent nuclear deterrent as he was; many of them believed its purpose was political rather than military. “I knew for 15 years that Trident was about keeping Britain as a permanent member of the UN security council and most of the men I served with knew it too,” he said. “We had an acute sense of, ‘If we mess this up, the UK will lose its place at the big boys’ table.’” The UK was “still concerned with projecting global power”, he added, whereas an independent Scotland would be concerned with “projecting global justice and peace”.

The crew of a submarine probably have a deeper knowledge of each other than any other workplace can provide, though of course Dalton has a political axe to grind and may not be the most reliable witness to their conversations. But who could argue with the idea that “status and influence” is the most persuasive answer to the question of what Trident is for?

There are other answers: to provide jobs and preserve skills; to sustain what’s left in Britain of high-tech shipbuilding and nuclear technology; to make the nation feel more secure in an increasingly dangerous world, where the number of countries with nuclear weapons looks certain to grow. But even in the cold war, the case for nuclear weapons went beyond the military. “To give up our status as a nuclear weapons state would be a momentous step in British history,” is the last (and by implication, not least) of the pro-Trident arguments in the Duff-Mason report. “It gives us access to and the possibility of influencing American thinking on defence and arms control policy and has enabled us to play a leading role in international arms control and non‑proliferation negotiations.”

Thatcher’s defence minister, John Nott, made a similar point about status and influence a few years later. Not to proceed with Trident when it was “probably inevitable” that other small countries would acquire a nuclear capability meant, he wrote, that “in the eyes of our allies, and of our enemies, we would seem quite a different nation (and the Conservative party quite a different party)”. A different nation, one whose political and military influence was commensurate with its economic size – there were few takers for that. “Britain is not just another country. It has never been just another country,” Mrs Thatcher told her interviewer Sir Robin Day during the 1987 election, when she faced a Labour party whose commitment to unilateralism was weakening but not yet expunged. “We would not have grown into an empire if we were just another European country,” she continued. “It was Britain that stood when everyone else surrendered and if Britain pulls out of that [nuclear] commitment, it is as if one of the pillars of the temple has collapsed.”

Tony Blair reached a similar view in 2006 after he and his chancellor, Gordon Brown, had debated the pros and cons of Trident renewal. Blair writes in his memoirs that it wasn’t an argument between “tough” and “pacifist” attitudes to defence: “On simple pragmatic grounds, there was a case either way.” But in the end he decided that “giving it up [was] too big a downgrading of our status as a nation, and in an uncertain world, too big a risk for our defence … but the contrary decision would not have been stupid.” Brown was similarly torn. Blair remembers telling him: “Imagine standing up in the House of Commons and saying I’ve decided to scrap it. We’re not going to say that, are we?” The cabinet agreed to renew Trident without any dissent, and on 14 March 2007 the House of Commons voted by 409 to 161 (the minority included 88 Labour MPs) to build the new Successor class submarines that, together with modifications to the D5 missile, would prolong the system’s life from 2020 to 2050.

Soon after Blair’s victory in 1997, a profile in the New Yorker mistakenly identified him as “Britain’s first post-imperial prime minister”. Nearly 20 years later, we still have not seen such a thing – at least not in Westminster. But Scotland is different. Many people inside Scotland, including its government, imagine their future as a country like Denmark: small, northern and prosperous, and committed to free education and welfarism. Not the least attraction of Scottish nationalism is that independence offers Scotland the chance to be what Thatcher called an ordinary country, freed from a burdensome British past – conquest, war, glory – of which Trident may be the last potent symbol.

Brendan O’Hara is the Westminster MP for Argyll, elected in last year’s SNP landslide. Faslane is inside his constituency and the preservation of jobs there is in an important local issue: when we met in London, O’Hara described the base as the future headquarters of Scotland’s armed forces as well as a naval base for the frigates and patrol boats that would comprise the Scottish fleet. But in his view, Trident can’t be justified on moral, economic or military grounds. “The world is changing – terrorism, the mass movement of people into mega cities, the conflicts over scarce resources, the migrations brought about by climate change … and yet the UK is hell-bent on going down the same 1960s route,” he said, echoing his party colleague Dalton. “Does anyone really think that nuclear weapons make the UK a safer place? For the establishment down here [London], Trident is a political weapon – it’s about preserving your status as a nation.”

In this way, the Trident argument has thrown up competing visions of a national future. After I left O’Hara’s office, I walked up Whitehall, past the Cenotaph and the statues of famous generals. Tourists gathered around the sentries from the Household Cavalry with their scarlet tunics and shining helmets. The grand offices built for an imperial bureaucracy rose tall on either side. Big Ben rang the half-hour. Big red buses obscured the base of Nelson’s Column.

England has this history to consider – a weighty and complicated inheritance that includes the Anglo-American relationship, Harold Wilson’s patriot in the pub and a popular media that never wants to let the idea of greatness go. It can’t easily cut this history loose, nor does it seem to want to. Wherever its road leads, it isn’t, or at any rate just yet, Tridentless towards Scandinavia.

8. Transparent oceans

Consider a series of possibilities that verge on the probable: 1) Scotland has a second referendum in the next 15 years; 2) it votes for independence; 3) negotiations to remove Trident begin; 4) Edinburgh and London reach a settlement, several years before the first of the new Successor submarines is scheduled to begin service in 2032 or 2033. Until recently, many people – including me – thought these four events would trigger a fifth: that London, facing the costs of relocating the Trident base would decide to abandon its nuclear strategy or at least this submarine form of it. The submarines under construction could be converted, scrapped or sold. Billions of pounds would have been spent, but future billions would be saved.

John Ainslie, the knowledgeable leader of Scottish CND, wrote in 2014 that he believed this to be “the most likely outcome” of Scottish independence – and the statements of politicians and military officers, apparently appalled by the cost, suggested he was right. In 2012, Nick Harvey, the armed forces minister in the coalition government, told the Scottish affairs committee that relocating the base outside Scotland would be “a very challenging project, which would take a very long time to complete and would cost a gargantuan sum of money”. A former Faslane commander, Rear Admiral Martin Alabaster, said that it would be very difficult – “in fact, I would almost use the word inconceivable” – to recreate the facilities elsewhere in the UK. The committee concluded that relocation would be “highly problematic, very expensive, and fraught with political difficulties”. An MoD source told the Guardian that the costs were “eye-wateringly high”.

There were strategic questions, too. Addressing the Royal United Services Institute in December 2013, General Sir Nicholas Houghton argued that defence spending should be refocused on the threats posed by terrorism, cyber warfare and climate change. His reference to the danger of stretching “insufficient resources” to buy “exquisite equipment” did not mention Trident, but the renewal programme stood out as the most obvious target of his criticism.

What was missing in these arguments, however, was the effect of Scottish independence on the government of the rest of the UK (rUK). Professor Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute has spent a good part of a lifetime studying Britain’s nuclear strategy. When I asked him if he thought independence was the beginning of the end for Trident renewal, he shot back: “Would the rest of the UK be prepared to give up its nuclear force when its reputation had already been damaged by the break-up of the union? I don’t quite see it. English opinion may argue the rights and wrongs of keeping a nuclear deterrent, but it’ll say, ‘We’re damned if we’ll allow Scotland to force us to give it up.’” Moreover: “This thing has been at the centre of the British state since the 1940s. If we scrapped it, the message to the countries that matter to the UK – to the US, to our European neighbours, to Canada and Australia – would just be puzzling. Why are you doing it at this moment? Is the UK bankrupt? It wouldn’t be a good message!”

In other words, Scottish independence would if anything intensify the rUK’s need to perpetuate the nuclear deterrent. In a paper published by the Royal United Services Institute in 2014, Chalmers examined the case for rebasing the submarines at the present Royal Navy dockyard at Devonport and building a warheads dump and loading jetty (the equivalent of Coulport) on the Cornish coast near Falmouth. He estimated the cost, excluding land purchase, at between £3bn and £4bn over a building programme lasting 10 to 15 years, and predicted fierce local opposition. But despite these “significant political and financial barriers”, he and his co-author Hugh Chalmers (no relation) thought it might be “the best available option within rUK”. A cheaper solution in which British submarines sailed from French or American bases has practical difficulties (and would make the claim of independent control perhaps conclusively unsustainable).

But, waiting to break surface from below these essentially political arguments, are two forbidding technical challenges. The first concerns the UK’s capability as a submarine builder – can a country that has been so industrially eviscerated actually build them? The story of the Royal Navy’s new Type 45 destroyers, recently revealed to have a fundamental flaw in their power system, is hardly a good omen. The construction of the Astute class attack submarines (SSNs), of which seven will eventually be built, has been troubled too. Hennessy and Jinks relate the events in their submarine history – how the work of warship design had been traditionally fulfilled in-house by the MoD’s Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, and how, by the time the first of the Astute class was ordered in 1997, a lot of this responsibility had been transferred to the builder. The MoD, in the words of an American industry report, had lost its “ability to be an informed and intelligent customer”. Lack of orders at the shipyard meant that the workforce had shrunk to 3,000 from the 13,000 employed at the height of the Vanguard programme. Many highly skilled engineers and constructors had left; layers of expertise had gone missing. The building schedule quickly ran into trouble – by 2002 the project was running three years late and several hundred million pounds over budget – and was rescued only when the MoD secured the help of more than 200 designers and engineers at the American submarine builder General Dynamics Electric Boat, which sent over a senior member of its staff to manage the project.

A lesson has been learned: engineers from Electric Boat have been involved in the design of the Successor submarines from the beginning – about 40 of them now work on the project in the UK. But several innovations in the Successor programme make it an even trickier proposition than the Astute class – they include a new version of the Rolls-Royce reactor; a new propulsion unit adapted from an American design; and a joint missile compartment that will suit the needs of both British and American boats. Foreseeing problems ahead, last year’s defence review promised a new MoD team headed by “an experienced commercial specialist”, who would have “the authority and freedom to recruit and retain the best people to manage the submarine enterprise”. Again, the language is opaque. What it may conceal is a problem that is likely to stretch the capabilities of even the most resourceful engineers and submariners: the problem of transparent oceans.

When in 1956 Khrushchev hailed the submarine as the great naval weapon of the future, the underwater made a marvellous hiding place. Submarines were hard for an enemy to track and find. “Stealth” was their operating principle – the Royal Navy remains proud even now of how its ballistic missile submarines avoided detection by Soviet attack submarines whose main purpose in the cold war was to find them. It was this combination of invisibility and mobility that had recommended them as missile platforms when land and air-based systems became vulnerable. But what if, thanks to new methods of detection, the sea became no more secure a hiding place for the submarine than the air was for the bomber? A growing number of military analysts think that technical developments are moving quickly in that direction. One of them is Paul Ingram, the director of the British American Security Information Council, a non-proliferation thinktank. According to Ingram, the “underwater battle space” will be transformed with the massive deployment of cheap sensors that will operate the sound equivalent of a net across relevant parts of the ocean. Additionally, shoals of underwater drones could be positioned or dropped at the entrance to the Firth of Clyde (or perhaps by that time, off Cornwall), ready to peel away and follow any submarine setting out on patrol; sensors that are acutely sensitive to unnatural water movement, many miles distant, could pinpoint a revolving propeller. How the Successor submarines would be able to avoid detection in this new environment was far from clear, Ingram said.

Devices like these have still to be perfected, but the world’s militaries are pouring money into their development, At Nato’s Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation near La Spezia in northern Italy, and at more lavishly funded laboratories and workshops in Russia, China and the US, people go to work every day to make the big missile submarines redundant. By the time the first Successor submarine starts on its maiden voyage – 16 or more years from now – it may be as elusive to a sophisticated enemy as a white-hulled cruise ship.

9. Our battleships

I first saw Faslane at the age of 13. One of Britain’s last battleships, HMS Anson, was being dismantled at the breaker’s yard that in those days occupied the bay. When I looked out from the train that summer afternoon in 1958, I was looking at a battleship that, incredible as it seems to me now, was only three years older than I was. The Anson made her first voyage under the white ensign in 1942. She and her sister ships King George V, Duke of York and Howe all reached the breakers’ yards within months of each other in the late 1950s, none of them having spent more than 10 years in active commission. The unluckier fifth sister, the Prince of Wales, lasted only 10 months before Japanese torpedo bombers sank her and the battle-cruiser Repulse in the South China Sea in December 1941, three days after Pearl Harbor. These were well-armoured ships, returning fire and moving at speed when the aircraft attacked them. The shock to Britain’s naval prestige was severe. Nothing quite like it had happened before.

The war carried on. Battleships were occasionally useful – pounding Normandy with shellfire, for instance, before the D-day invasion. But what had seemed like advanced thinking on Admiralty drawing boards in 1936 were by 1950 obsolescent hulks. An earlier HMS Vanguard, predecessor to the present nuclear submarine, was the last battleship to be launched anywhere in the world; constant changes in design – many made in the light of the loss of the Prince of Wales – kept the hull on the slipway through most of the war and she was commissioned into the navy a year after the fighting in Europe had ended. Retired after nine years and scrapped, again at Faslane, in 1960, her most important voyage had been to take King George VI to a royal tour of South Africa. As a small boy, I saw her anchored a mile out to sea from our village, a big, grey two-funnelled shape with gun turrets that pointed straight ahead. “There’s the Vanguard,” people said, pointing through the haar, but she was there one morning and gone the next.

The British navy has shrunk almost beyond recognition since then. In the book by Hennessy and Jinks, a submarine commander says that its personnel could “fit into Stamford Bridge and leave room for the away fans”. Despite the arms lobby and veterans’ Save the Navy campaigns, ships and crews have lost their purchase on the national imagination. Britain has become what sailors call “sea blind”, while the British military as a whole has still to recover the reputation and confidence that it lost in the misadventures of Iraq and Afghanistan. And yet Trident survives – and it seems will go on surviving despite the questions over its cost, purpose and durability and the ominous parallels with the battleship.

Should we renew it? As someone of a certain generation and disposition, I find it hard to be absolutely sure. The boy who loved ships sits at odds with the teenager who wanted to ban the bomb. The world grows more hostile; unlike Jeremy Corbyn, I don’t believe that Britain’s renunciation of nuclear weapons would set an example pour encourager les autres. The sight of a nuclear submarine moving down the Clyde can still excite me in some unplumbable and perhaps regrettable way; the fact that Britain can still build them, when it builds so little else, is remarkable. But to set against these feelings, which come out of personal history and watching the news, stands the unassailable fact of Trident’s expense and the growing question of its usefulness.

It has been a great triumph of British governments, and particularly the present government, to have successfully depicted any opposition to Britain’s nuclear strategy as the treacherous work of people “who cannot be trusted with the defence of the nation”.

History tells a more muddled story. Nuclear weapons were never the done deal, the only way forward, that the ebullient certainties of politicians such as the present defence minister, Michael Fallon, would have us believe. They have been contentious inside the British establishment for 70 years, never properly scrutinised because opposition to them was usually based on moral and not practical grounds. If we didn’t already have them, would we want to acquire them? Nobody I talked to in the course of reporting this piece thought so, but the question is hypothetical. Trident may or may not keep us safe. The hope is, and always has been, that it will keep us important.

Main photograph: Thomas McDonald/CPOA

This article was amended on 11 February to correct the date of the sinking of the battle-cruiser Repulse and the Prince of Wales in December 1941, and to clarify that the Atomic Weapons Establishment is run, but not owned, by a consortium of private companies.

This article was amended on 11 February to remove a graphic of a D5 Trident missile that was incorrectly labelled.

This article was amended on 17 February to correct David Owen’s ministerial role in 1978. He was foreign secretary, not defence secretary.

THE LONG READ

No comments:

Post a Comment