|

| Patricia Highsmith |

How a Swiss editor wrangled Patricia Highsmith’s messy diaries into a volcanic book

Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995

Edited by Anna von Planta

Liveright: 999 pages, $40

The mystery novelist Patricia Highsmith dedicated one of her best-known thrillers, “Strangers on a Train,” to “all the Virginias,” and her diaries are packed with them. It was a popular name in the 1940s, especially among Highsmith’s lovers, and sorting them out was among the easier tasks faced by editor Anna von Planta in the course of a 25-year project: to reveal one of the last century’s most intriguing, complex and misanthropic authors in a single, honest and readable volume.

At 999 pages, “Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995,” out next week, is not exactly lean or economical. It begins when the Texas-born Highsmith was a Barnard undergraduate and charts her booze-fueled odyssey through course work, short-story drafts and serial affairs, mostly with women. After college, she and her prose grow more confident. She publishes “Strangers” in 1950 and “The Talented Mr. Ripley” in 1955; her 1952 lesbian novel, “The Price of Salt,” gains a following for “Claire Morgan,” Highsmith’s pseudonym. She moves to Europe to evade McCarthy-era persecution. And by the 1970s, after she has burned through countless countries, cigarettes and lovers, her journal often erupts in paranoia: “I swing these days between resentment (a sense of being badly treated by other people) and aggressive hatred.”

Yet despite the extremes of mood and tone, this volcano of a book, winnowed from more than 8,000 pages of notebooks and diaries left behind when Highsmith died in 1995, is in fact a model of compression.

It also has a striking immediacy. “Here you are — right in her life as it happens,” Von Planta told me over Zoom from Zurich, where she edits for the Swiss publisher Diogenes Verlag. “In hindsight, you can connect the dots. But you can’t know in the moment. You can only know afterward.” Highsmith’s journals allow us, she says, “to trace her evolution. And she’s so honest and authentic. She doesn’t spare herself — and she certainly doesn’t spare others.”

Von Planta may know Highsmith better than Highsmith knew herself. She and Daniel Keel, Highsmith’s literary executor and founding publisher of Diogenes, were the first people —besides Highsmith’s snooping lovers — to set eyes on the journals in the Swiss home where the author died.

“Daniel and I were looking for unpublished short stories,” she told me. They found “little snippets of manuscripts” and a trunk of her drawings, but the journals were not in plain sight. Von Planta suspected Highsmith would have hidden them in a clean, dry, safe place — like, say, a linen closet. So they located hers. And there, beneath the “beautifully ironed sheets,” was a half-century of private writings.

The thrill of discovery was short-lived. Soon Von Planta had to whip the massive trove into something publishable — a task that Robert Weil at Liveright, the book’s American publisher, calls “herculean.”

“For 15 years, I asked Anna for this book and she always said it was coming,” Weil said. “She didn’t mention there were 8,000 pages.”

Keel died in 2011; Von Planta persevered.

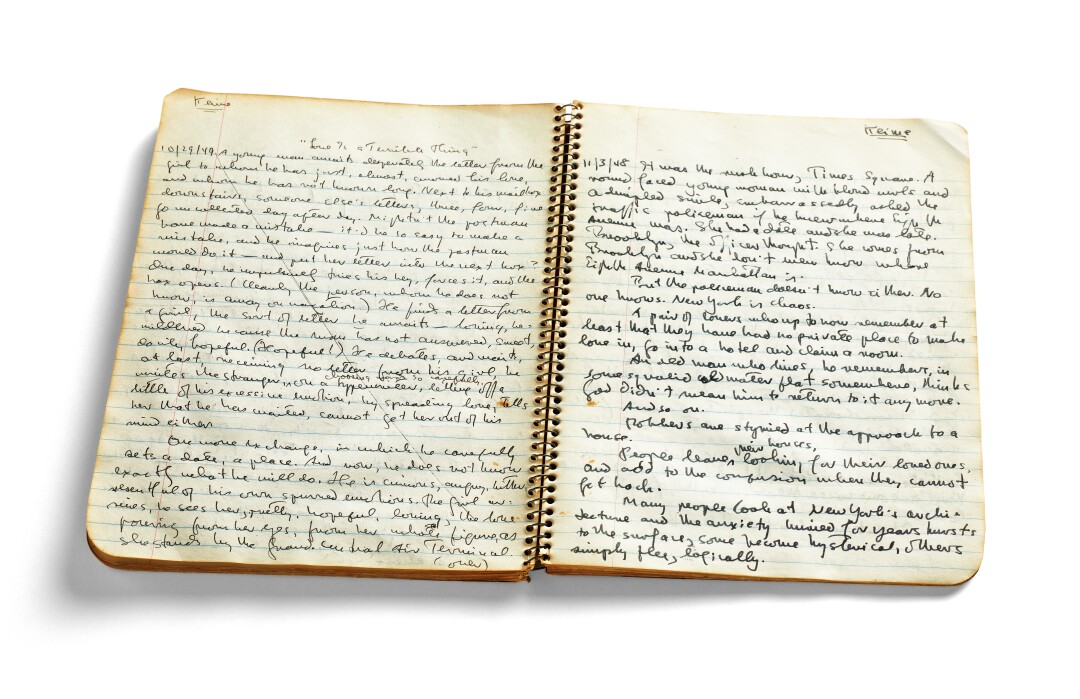

The notebooks were not user-friendly. They were filled with cramped, jittery handwriting and no margins, wedged into the spiral-bound Columbia University notebooks that Highsmith’s close college friend, Gloria Kate Kingsley Skattebol, mailed to her after she moved away from New York.

“We had to have all the material transcribed by two people,” Von Planta continued — one for the spiral-bound work notebooks, another for the mismatched assortment of personal diaries. This alone took two years. She then gave the massive transcription to Kingsley Skattebol, who made corrections and gave Von Planta “indiscreet commentary” about the lovers Highsmith had identified only with initials. Von Planta allowed some to keep their anonymity. One particular Virginia did not: Virginia Kent Catherwood, a married Philadelphia heiress who might have been Highsmith’s first great passion.

Some entries read like taunts to future editors. “Why do I keep writing?” Highsmith asks in 1970. “It is too utterly boring and too much for anyone to plow through after I’m gone.”

Von Planta first met Highsmith in the garden of a Zurich hotel after Keel had acquired the rights to her novel “Found in the Street.” The year was 1984. “I was barely 27 years old— a junior editor.” But her English was the best in the office, thanks to a yearlong internship with a literary agent in New York.

She found the American novelist sitting at a French metal table. “I extended my hand, European fashion, and she just left the hand dangling, ordered a beer, and fell silent.”

But Von Planta pressed on. She loved the central character in “Found in the Street” — a young girl from the country who comes into her own in Manhattan. But the book’s setting “felt out-of-time, or rather, in a way, like a fairy tale,” because although it was supposed to take place in the 1980s, “it felt like the 1940s or ’50s.”

To Von Planta’s surprise, Highsmith looked up. “Well, I don’t know about the timeless and I don’t know about the fairy tale,” she said. “But in the 1940s I was like this young girl. I lived in New York, in Greenwich Village.”

“Then we started talking,” Von Planta said, “and it went fine. She even laughed.”Back in the office, Von Planta told Keel: “Maybe I’m not the right person for this. Because it took me a long time to get her talking.”

“What? She talked to you?” he said. “It took me ages to get more than a yes or no answer.”

By then, Highsmith had no permanent New York publisher, having been rejected by major presses despite her bestsellers. Keel persuaded her to make Diogenes her publishing home, positioned her as a literary novelist rather than merely a genre writer, and found the prickly novelist an editor with whom she could get along.

Von Planta was well-suited in other ways to edit the diaries. They are written in German, French, Spanish and Italian. “In Switzerland, we can’t go very far without dialect so we learn languages fairly early in our lives,” she says. Her childhood dialect was so distinctive that even standard German was a foreign language. When she was 6 years old, her father, a physician, moved the family briefly to London, which jump-started her mastery of English.

Such fluidity turned out to be essential. Highsmith wrote early entries in German to avoid the prying eyes of her family. In 1954, after her partner, Ellen Hill, had sneaked yet another peek at her diaries, she gave them up altogether, writing only in her notebooks for seven years. Yet the languages she wrote in were not exactly idiomatic. Much of her German resembles English with foreign words.

The subject of several lengthy biographies, Highsmith isn’t exactly an unknown quantity. We know of her volatile on-and-off liaison with Hill and her tragic entanglement with a married Englishwoman who had a child. But the diaries provide a newfound layer of intimacy. Editing them, especially as Highsmith gets darker and stranger, was an intense experience all its own.

“She got into my head,” admitted Gina Iaquinta, who worked on the American edition. “I was editing the book about this time last year — at the height of the pandemic. And my anxiety went through the roof. She’s so paranoid. She made me paranoid.”

Among the freshest revelations are Highsmith’s intense and enduring relationships with animals. Early on, the human object of her obsession on Monday was likely to be discarded by Tuesday. But Highsmith was not so mercurial with cats. At the end of 1969, she is consumed with grief after the sudden death of her treasured cat, Sammy. She is also eager to leave France for England. Out of this combination came a bitter eulogy: “In a countryside of pigs and people unattractive to look at, I appreciated her beauty especially. Her demands I adore. … It is a final blow.”

Highsmith also had a creepier passion: snails, which she kept as pets throughout her life. ln 1964, traveling between France and England, she smuggled her pet snail collection through customs in her bra. What the journals don’t explain, however, is: Why snails?

“I think it started with a great love — an obsessive love,” Von Planta said, not for the snails but for Kent Catherwood. “They had pet snails together. It bonded them. You share a dog or a cat with your lover. They shared snails.”

Snails also exhibit no outward gender identity until the moment of copulation. This ambiguity may have appealed to Highsmith. There’s a dreamlike entry from 1942, Von Planta told me, when Highsmith appears to meditate on her own sexual identity: “You looked into a cluttered top drawer and you expect to see either a man or a woman reflected in it, and it is very disturbing when you see neither, or both.”

Highsmith had no such trouble categorizing others. By the 1970s, she had broadened the targets of her invective. “She lashes out against Catholics, Jews, America, her neighbors, French people in general, and French bureaucracy,” Von Planta writes in an introduction to that era’s letters. This, too, posed a challenge for Von Planta and her colleagues: Do they omit offensive remarks or remain true to Highsmith? They opted for authenticity, only cutting for redundancy.

After run-ins with French authorities over taxes, Highsmith moved to Switzerland, spending her final years in the village of Tegna.

Von Planta cannot forget her last visit, four months before the author’s death — and her walk from Highsmith’s house back to the train station. “It was a long street with a bend. I was looking back before turning and I thought: She would never stand there.” But there she stood. And in that moment — that frozen, evocative moment, “I knew I would never see her again.”

The moment, as it happened, was not a farewell. It was an invitation, the nature of which she would not understand until she and Keel found the journals. Highsmith gave Von Planta access to her most intimate thoughts. She trusted her to shape them — yet to retain their integrity — before sending them out into the world.

Lord, author of “The Accidental Feminist,” is an associate professor at USC.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

No comments:

Post a Comment