|

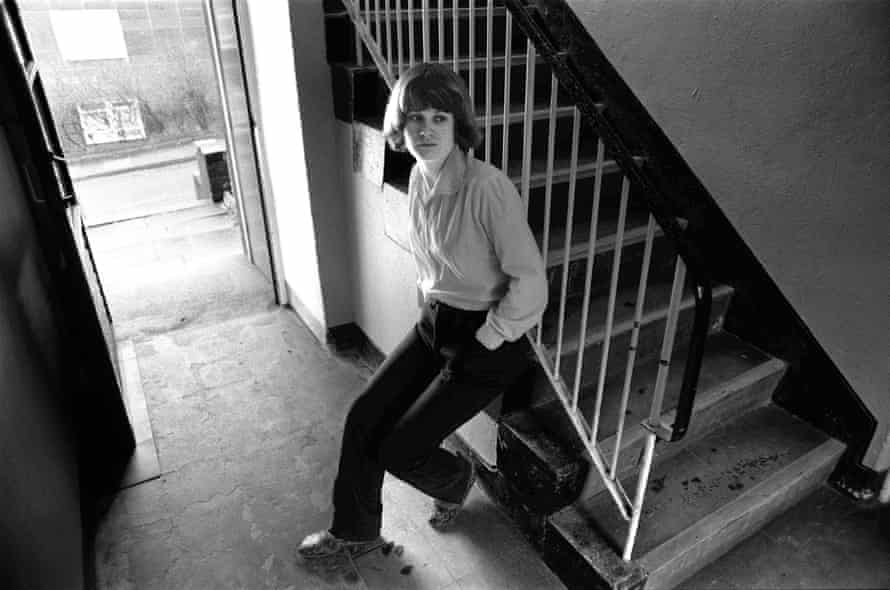

| Andrea Dunbar |

Rita, Sue and Bob today: Andrea Dunbar's truths still haunt us

Dunbar’s bleakly funny tale of a menage a trois captured 80s austerity. What can her defiant heroines tell audiences today?

Thursday 14 September 2017

‘This is life,” Andrea Dunbar told the Yorkshire Post in 1987, defending the film version of her play Rita, Sue and Bob Too. “The facts are there.” Dunbar was adamant about telling the truth in her work, insisting “you write what’s said, you don’t lie”. Her second play, an unvarnished tale of a married man having an affair with his teenage babysitters, still has that startling matter-of-factness today.

As a single mother living in poverty on a council estate in Bradford, Dunbar had a perspective that has rarely been shared on major stages. It’s hard to imagine a play like The Arbor, the autobiographical script she wrote as a teenager, making it to the stage now. In another age of austerity, under another Tory government, putting on her work is an implicitly political gesture.

Dunbar, though, was more concerned with everyday drama than with ideology. There’s only one explicit political critique in Rita, Sue and Bob Too, and it comes from one of the play’s least sympathetic characters. Bob tells his young paramours “there’s no hope for kids today, and it’s all Maggie Thatcher’s fault”. But the lecture’s quickly dropped – Rita and Sue are far more interested in getting a “jump” than in chatting politics.

Out of Joint’s revival, directed by Dunbar’s early champion Max Stafford-Clark and Kate Wasserberg, preserves that unabashed pursuit of pleasure. The lights come up to the distinctive opening beats of Tainted Love, and between scenes the characters dance to a soundtrack of Blondie, Culture Club and Bowie. No one throws themselves into it more than Rita (Taj Atwal) and Sue (Gemma Dobson), who enter with equal vigour into their menage a trois with Bob.

The sex at the centre of the play is both joyful and mundane. The first scene, in which Bob (a swaggering, long-haired James Atherton) takes turns shagging the two girls in his car, is sex at its most unsexy. It’s awkward, bum-jiggling and intensely funny. Yes, funny, despite the queasy undertones of a man in his late 20s seducing a pair of 15-year-olds. There’s no judgment in Dunbar’s play or in Stafford-Clark’s and Wasserberg’s direction, which in some ways – and despite the near-constant humour – makes it all the more appalling. When the girls get blamed and labelled “sluts”, there’s a bleak sense that this is just how it is.

The Buttershaw estate, where Dunbar lived and died, and where she got the inspiration for her plays, looms large in this staging, as it does in all treatments of the playwright’s life and work. It’s there, exerting an irresistible pull, throughout Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, Adelle Stripe’s compelling new fictionalisation of Dunbar’s life. And in Clio Barnard’s extraordinary 2010 film The Arbor, which unsettlingly places interviews with Dunbar’s family in the mouths of lip-syncing actors, while scenes from the writer’s work are also staged in the middle of the estate, with residents looking curiously on.

In Out of Joint’s Rita, Sue and Bob Too, tower blocks rise up on either side of the stage, while the back wall shows a view of Bradford spread out beneath the moors. Tim Shortall’s design, though overly literal in its evocation of Buttershaw, is a reminder of the limited horizon Rita and Sue have ahead of them. The reclining car seats manoeuvred around the stage are a fleeting symbol of freedom and fun; when things begin to turn sour, they get briskly removed. In another of the transitions, the older generation tug factory overalls on to a reluctant Rita and Sue, dressing them in the futures they were always destined for. The laughter begins to curdle.

In some ways, though, there’s an innocence to these scenes, underlined by the dorky dance moves and 80s party tracks. When I spoke to director John Tiffany about his recent revival of Jim Cartwright’s Road, set in Lancashire and written in the same period as Rita, Sue and Bob Too, he observed that the play depicts a community pre-heroin. As Dunbar’s daughter Lorraine puts it in A State Affair, the verbatim play that revisited Buttershaw in 2000, if it was written today, then “Rita and Sue would be smackheads”.

Dunbar told the truth, but in the end it didn’t make a difference. “They’ll forget about us all by tomorrow,” she astutely predicted of the middle-class audiences fascinated by the drama of the Buttershaw estate. When Dunbar died of a brain haemorrhage in 1990 at the age of 29, she was stuck in the same poverty in which she was born. For the people Dunbar wrote about – and, as Barnard’s film devastatingly shows, for her own children – life has only got worse. As Sue’s mum recognises, the best that kids like Rita and Sue can hope for is to get their fun while they can.

No comments:

Post a Comment