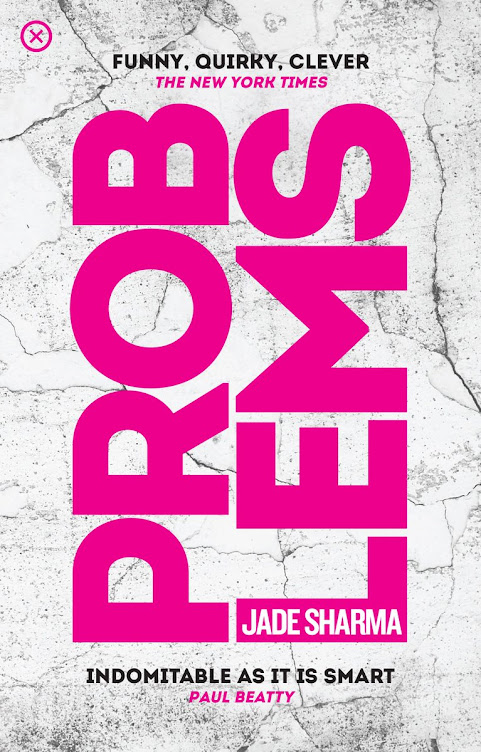

We're delighted to present an extract from Problems, the debut novel by Jade Sharma, published by Tramp Press.

"This book is definitely about disillusionment"Jade Sharman

Dark, raw, and very funny, Problems introduces us to Maya, a young woman with a smart mouth, time to kill, and a heroin hobby that isn't much fun anymore. Maya's been able to get by in New York on her wits and a dead-end bookstore job for years, but when her husband leaves her and her favorite professor ends their affair, her barely-calibrated life descends into chaos, and she has to make some choices.

When I was a kid I brought home a picture from art class. My mother stared at it with a puzzled look and said, ‘Trees aren’t purple. What is wrong with you?’ I watched it sway in the air before it landed in the garbage. On the fridge was a test my brother had gotten an A on. A concise little story that played well in therapy.

Before I was about to hang up self-righteously, she said, ‘I’ve had trouble swallowing lately.’ And just like that, she’d won. It didn’t matter what she had ever done to me. She was sick, and she was my mom. Emotional kryptonite. The lump in my throat. With a snap of her fingers she could turn me into a lost six-year-old with tears running down my face, just wanting my mommy.

Somehow that’s what happens when you deal with the very first person you met on Earth.

I stared out of the messed-up bus window at a drunk taking a piss. This dirty town. ‘I don’t know where all this mucus comes from,’ she said. I listened with an overwhelming sense of fear and dread as she told me all the fucked-up things her body was doing.

It doesn’t matter how old you are, after your mom dies you will still feel like an orphan, out there completely alone in the world.

You always feel like a champ when you make your mom laugh.

I picked shreds of tobacco from the Chap Stick, listening to my mother. I found myself saying, ‘I would come, but I have a lot going on right now.’

I loved my mother. I felt bad that she wanted to love me, but she did all the exact wrong things. I felt bad she could be so cruel, like when she threw in my face that I went to a shrink, as if that gave her the authority of the sane, and dismissed all my grievances. Not that it was her fault. Nothing was her fault. It was the way she was raised. She had my brother when she was just nineteen years old; like, what did she fucking know about anything? She’d never lived on her own. She went from her parent’s house to her husband’s house. Her husband. He wasn’t easy. She was so bright and crafty, and she could have lived a whole life and not just been a glorified servant. Who could blame her for being nuts? Her father and her husband had deprived her of being a person. She was raised to believe the best thing to be was a wife and mother. It was so sad. And we were so hard on her. What do you do when your teenage daughter tells you she wants to die? When she cries and screams and disappears for days? What would you do? What would I do?

My brother told me there was a chair in her shower now. It was the saddest thing I could imagine.

Indians are always cremated. The body that grew from a baby into my mother would go into the oven and turn to ash with bits of bone.

It’s important to drink milk because calcium is what bones are made of.

Her ashes would go where my father’s had gone: The dark cloudy waters of the Ganges. Where sick people bathe. Where there is someone pi**ing, someone shi**ing, and someone vomiting right now. And then my brother.

And then, finally, me, the baby of the family, the last one to be dumped in the water, forgotten and dead, just like everyone else.

We would be dead, so we wouldn’t care how disgusting the water was.

It took all the way from Fourteenth and Fifth down to Astor Place to shake off the guilty feelings.

I walked into Starbucks. I was always late to work. But after that phone call, I deserved a treat. A skinny caramel latte was 100 calories. But I needed all the sugar and caffeine and fat of a mocha frap, with a big fat unnecessary swirl of whipped cream on top, because death is serious business.

All the women in Starbucks were wearing cardigans. All the women of f**k- able age, anyway. It was as if someone from wardrobe had come in with a rack of cardigans, and each of the women selected one. There’s this moment in New York City when all the women are wearing different versions of the same thing, as if they all had gotten a memo, and you have to decide, Am I going to join this trend?

If you don’t get on board, you will feel like an out-of-touch loser (NYC is like high school: trends, being judgmental, and how impressive it is when you find out someone has a car – Really? You have a car. But if you do go with the trend, you will feel like a poser, no matter how much you actually like the scarf or skirt or whatever it is. Everyone who passes you will think you are just another follower. Loser or poser?

I walked into the bookstore at a casual pace, sipping my drink, chewing on the straw lackadaisically as I did not rush down the stairs.

‘Jeez, don’t you ever take a break?’ I asked Ethan, who was sitting with his legs up on the receiving table with his eyes closed.

‘I’m afraid of intimacy so I bury myself in work,’ he said, not opening his eyes.

No comments:

Post a Comment