|

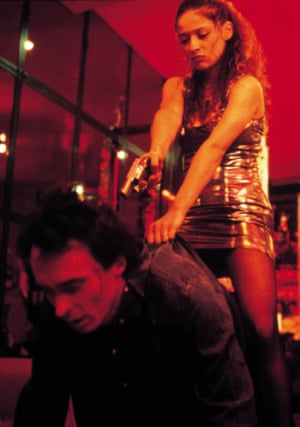

| Decades on the frontline of the gender war … Virginie Despentes. Photograph: Ed Alcock |

Virginie Despentes: ‘What is going on in men’s heads when women’s pleasure has become a problem?’

The wild child author of Baise-Moi and former sex worker has completed a trilogy, Vernon Subutex, which has secured her renown as a ‘rock’n’roll Zola’

Ten of the best new books in translation

Friday 31 August 2018

I

n her living room in northern Paris, Virginie Despentes, a former punk and wild child of French literature, sits on her sofa with coffee in a Motörhead mug, rolling a cigarette and reflecting on the passing of time. “I’ve changed a lot as a person – the anger and anxiety isn’t the same,” she says.

It is almost 25 years since Despentes burst on to the French literary scene with her debut novel Baise-Moi, a rape revenge story that she began writing aged 23 while she was also occasionally a sex worker. In 2000, when she directed the film version, working with female pornography actors, it was banned in France for a time, and became a cult hit across Europe. Despentes, who took her pen name from the area in Lyon where she was a sex worker, was branded crude, outrageous and refreshing – the working-class daughter of postal workers from Nancy in north-eastern France became literature’s “voice of the marginalised”. Since then she has written 10 more books, won literary awards and redefined French feminism in her 2006 manifesto King Kong Theory, in which she detailed being raped at 17 while hitchhiking with a friend, when they were attacked and threatened with a rifle by three young men.

But now, at 49, it is her funny, irreverent and scathing trilogy about contemporary Paris Vernon Subutex that has cemented her status as a “rock’n’roll Zola”. It has sold hundreds of thousands of copies in France, won a clutch of prizes, been shortlisted for the International Man Booker prize, adapted into a big-budget TV series and translated across the world.

The saga centres on a record-shop owner who, when his shop closes, is evicted and has to blag nights on sofas from old acquaintances before drifting into homelessness. He was once friends with a rock star, Alex Bleach, who was found dead from an overdose in a hotel room, and has some video tapes that several people are hunting down. The sweeping cast of characters reflect all strata of society, from retired pornography actors to a vile sex predator film producer (it was written before the accusations against Harvey Weinstein were made public), an extreme-right thug who works in a high street clothing store and a Muslim student in a headscarf who – pointedly – is neither submissive nor radicalised, but simply knows her own mind. Despentes says she is sick of veiled women being stereotyped and made a political target in France.

Vernon Subutex is written like a TV series – an art-form she thinks has taken over from cinema “and perhaps will even take over from the novel”. The trilogy chronicles what she sees as the creeping advance of far-right ideas through French society: casual racism and disdain for the poor.

“It’s about the passage from the 20th to the 21st century and a feeling in France of losing the dominant position,” she says. “Western Europeans have been privileged from birth, feeling like the dominant power. It’s also about a certain loss of virility and how one adapts to that, men or women.”

Despentes, who has spent decades on the frontline of the gender war, thinks we’re in an era of “great change”, citing the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. “This past year was pivotal,” she says. “For the first time, we’re seeing young women who view being at ease in the public space as their right. It has been a revolution ... Never was there a generation of women who were told so clearly: when you go out of your front door there is absolutely no reason you should come back in the evening down because a man has touched or heckled you.”

#MeToo has kindled a revival of interest in Despentes’s King Kong Theory and a theatre adaptation returns to Paris this autumn. She thinks it might take a decade before we can fully assess the impact of these movements and remains wary of a backlash from the patriarchy.

In Vernon Subutex, Despentes has created a male character who has captured the French imagination. In hindsight she feels readers and critics were a lot kinder to this hapless man than they would have been if it were a woman. “I think if there had been a female central character, the work would have been seen much less as a portrait of its generation and more as the story of a woman who messes up.”

From her window you can see in the distance the Buttes-Chaumont, the vast park in the 19th arrondissement where tower blocks rub up against gentrified streets, and in which much of her story takes place.

It was in this park that two Parisian brothers, the Kouachis, trained for jihad before carrying out the terrorist attacks on the magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015. The first volume of Vernon Subutex was published in France on the morning of those attacks. While Despentes was writing the third volume, the attacks on a Paris football stadium, restaurants and the Bataclan rock venue took place in November 2015. She altered the book to reflect society’s reaction.

“The issue of terrorism is unavoidable in a contemporary French novel,” she says. “Just as the topic of refugees, homeless people and the rise of the far right is inescapable. Because I really wanted to make this novel a snapshot of France.”

Despentes acknowledges the difficulties: “When there is a big terrorist attack, there’s stupefaction — that’s the whole point of terrorism. For several months after the Bataclan, I stopped writing; it was impossible to continue because it seemed such a piddling thing to be doing. But then I thought what I need is the book I want to read right now, so I got back to it.”

She pauses and says it might come as a surprise, but one of her biggest literary influences is Nick Hornby. “He’s got a way of writing about problems that when you read it, it’s almost feel-good. His books have been important to me in terms of learning what writing is, but they’ve also boosted my morale. There were times I wasn’t feeling great and I read two or three Nick Hornbys back to back and that perked me up.”

In terms of French culture and thought, she says the biggest talent is now among women of colour: the writers Léonora Miano and Faïza Guène, the rapper Casey, the essayist Rokhaya Diallo and the documentary-maker Amandine Gay. There had been so little airtime given to these perspectives for 30 years that now it’s like an “eruption”.

Despentes has said her own writing wouldn’t be what it was if she hadn’t given up alcohol at 30 and she is considering writing about addiction. At 35, she says, she “quit heterosexuality”. . “It’s easier to be a feminist when you’re lesbian. You’re not afraid of saying certain things, or of offending the person you live with because you’re too radical and your life isn’t in contradiction with your ideas.”

Two events provided the seed for the Subutex trilogy. One was the economic crisis and how easily people in their 50s can lose jobs and homes and not be able to get back on the ladder. The other was the death of the singer Whitney Houston. “When Whitney Houston died there were articles about her and the relationship she had with a particular friend, who wasn’t well known, who stayed in the shadows, but who some implied was her mistress. That’s where the idea came from of someone who wasn’t well known but who was friends with a famous singer.”

There is sex in Vernon Subutex, but Despentes says the trauma of the scandal around Baise-Moi runs deep and nowadays “there is a lot less sex in my books”; she feels many contemporary French writers are tending to “remove the notion of sex” and getting a better reception from critics because of it. But it still has a place in French literature and art, she says, and needs to be talked about. She describes herself as a pro-sex feminist. As a former pornography reviewer who still watches vast amounts of the stuff, she is concerned about changes to the industry and the humiliation of female performers. With ever younger children accessing adult films, she says there needs to be more public discourse, special portals providing pornography for teenagers, education that there are different types of porn.

“For a very long time, in the 70s and 80s, even 90s, pornography centred on a notion of women’s enjoyment. Today in international pornography – which all looks more or less the same – it’s the opposite: it’s a problem if a woman has any pleasure at all. Not all porn is about hatred of women but at the moment what is being watched is about that. What is going on in men’s heads, in their sexuality, when women’s pleasure has become a problem?”

She wishes there was more critique of this by men. “Very few are asking how pornography got like this, what behavioural issues are at play.”

Despentes also sees hypocrisy in the current arguments about prostitution and can’t understand why it isn’t treated by the law like any other work, and why men in positions of power, including male MPs, who use sex workers don’t seek to make their working conditions better. In King Kong Theory she wrote that having been a sex worker had helped her rebuild herself after rape. It’s about money, she says.

Today King Kong Theory, with its account of Despentes’s rape, is the book she is most often asked to sign at events – and by a growing number of young men. When it was published 12 years ago, her publishers refused to use “feminism” on the cover. “There was a French way of thinking then that feminism wouldn’t sell, that feminism would put people off, that feminism was over,” she says. “But I knew I wasn’t the only person interested in it, and now that’s clear”

• Vernon Subutex Two is published by Quercus.

No comments:

Post a Comment