Martin Beck’s Malaise

By Moody Sleuth

November 20, 2013

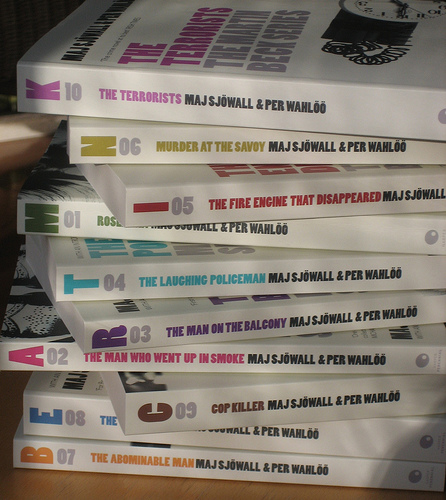

Sean & Nicci French, in their introduction to the fourth Martin Beck novel, The Laughing Policeman (Harper Perennial edition), remind us once again that Martin Beck was “the prototype of the brilliant tormented detective.”

Many other moody sleuths such as fellow Swede Kurt Wallander, Norwegians Konrad Sejer and Harry Hole, and Icelander Erlendur Sveinsson owe their existence to Martin Beck. Sean and Nicci French extend Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s influence to include the likes of Ian Rankin’s John Rebus and Thomas Harris’s Will Graham.

But we’ve been over this ground already. Let’s take a closer look at is what Sean and Nicci French say next: “Beck’s ‘malaise’ is all the more effective for being only partially articulated”

That sentence gave me one of those ‘ah-ha!’ moments, another clue as to why I prefer one moody sleuth over another, and why I find so few books worth re-reading.

|

| Maj Sjöwall |

If you’re up to it, there’s an excellent, if rather ‘scholarly’, paper “Articulation, the Letter, and the Spirit in the Aesthetics of Narrative” by Hugo Liu of the MIT Media Laboratory – Massachusetts Institute of Technology in which he explains how a reader benefits from ‘partial articulation’ within a narrative:

“Partial articulation nudges the reader toward a particular interpretation and appreciation of a narrative without the obtuseness of explicit exposition. The freedom of discovery is preserved for the reader…”

I find Sean and Nicci French’s assessment absolutely ‘spot on’ and I’m grateful for Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s restraint. That they chose to only ‘partially articulate’ Beck’s ‘malaise’, as opposed, say, to allowing their moody sleuth to wallow in his angst and ailments, is, in my opinion, a blessing.

Keeping this idea of ‘partial articulation’ in mind, I want to take a closer look at Martin Beck alongside a couple of the other moody sleuths I’ve written about over the past year:

The Frenches suggest there is almost a surfeit of causes [for Beck’s malaise]: his weariness after years as a detective, his failures as a family man and, suffusing everything in all the books, a sense that something has gone profoundly wrong in social democratic Sweden, as if the crimes he faces are superficial symptoms of a much deeper historical crisis.

This train of thought is echoed by Jay Phelan in his article “The Scandinavian Detective and the Dissolution of a World” in the ecumenical journal Pietisten:

“These detectives reflect the ills of Scandinavian society in their own persons. Like Beck, their marriages and other relationships with members of the opposite sex are a mess. Wallander and Erlendur are divorced and have troubled relationships with their former wives and their children. They are perennially depressed and frequently truculent. Their work habits, their eating habits, and, especially, their drinking habits render the sustaining of relationships difficult if not impossible. Harry Hole’s drinking puts not only his key relationships in question, but his job and his very survival at risk. They are alone, even when surrounded by others. Their peers may respect them, but seldom understand them. Beck has a persistently queasy stomach. Wallandar is an insomniac. Hole is a binge drinker. Erlendur is a misanthrope. They have all received and inflicted psychic wounds.”

Troubled detectives tend to lead troubled lives, have troubled relationships, and suffer from some physical or psychic malady, but when the author writes to address political and societal issues, as do Scandi-writers Sjöwall and Wahlöö, Henning Mankell, Arnaldur Indridason, Greek Petros Markaris, and by extension, many other crime-fiction writers around the world, we might interpret the physical and/or psychological ills and relationship difficulties of their protagonists as reflecting the problems their creators identify within the societies they inhabit.

Throughout most of the Martin Beck series, we catch Beck coughing, sniffling and shivering through one cold after another, or trying to ignore chronic stomach pain, but Sjöwall and Wahlöö never belabor us with superfluous detail; it’s always just ‘snippets’ dropped into the narrative, each either serving to bring in other elements of the story, such as demonstrating character or relationship, or reminding us of another situation in his life.

A case in point: Martin Beck is at police headquarters with his co-worker and friend Lennart Kollberg, examining some sketches pertinent to a murder case:

“Beck was seized with a long, racking cough, then he put his hand thoughtfully to his chin and went on studying the sketches.

Kollberg stopped his pacing, looked at him critically and declared, ‘You sound awful.’

‘And you get more and more like Inga every day.’” (Inga is Beck’s wife)

In another instance, a passage briefly mentioning Martin Beck’s cold is an opportunity to set the scene, to give us a taste of a Stockholm’s bitter winter weather, plus remind us of Beck’s increasingly unhappy relationship with his wife:

“An icy gust of wind whipped a shower of needle-sharp grains of snow against Martin Beck as he opened the main door of police headquarters, making him gasp for breath. He lowered his head to the wind and hurriedly buttoned his overcoat. The same morning he had at last capitulated to Inga’s nagging, to the freezing temperature and to his cold, and put on his winter coat.”

Though Martin Beck’s malaise may reflect the ills of Swedish society, he’s definitely not a mouthpiece for his creators’ beliefs. Sjöwall and Wahlöö brilliantly leave that job to secondary characters, often minor ones, and most often it’s situations within the stories that subtly underline their criticisms.

By contrast Icelandic Detective Inspector Erlendur’s malaise is mental and not physical; it often plays out in his interactions, mainly arguments, with his drug-addicted daughter, Eva Lind. It’s apparent that he blames himself for his daughter’s state, but doesn’t know what to do about it. All of his familial relationships seem fraught with anguished complexities, not just in regard to his ex-wife and children, but extending into a dismally unhappy childhood, guilt over a lost brother and unresolved issues with his own father. Erlendur retreats from his troubles by immersing himself in old Icelandic stories describing ordeals and fatalities in the wilderness. We witness his battles and the interludes, and get Erlendur’s thoughts on these, but writer Arnaldur Indridason wisely refrains from using explicit exposition. The connections we readers make are as much from what is not said…

Indridason doesn’t appear to harbour reactionary ideologies regarding Iceland’s political or societal woes; instead he tends to address particular issues within the themes and story-lines of each book, allowing the characters to do the questioning. Erlendur tends to focus on the themes as they relate to his own relationships, fatherhood, missing identities, lost childhood, etc., where again, the reader is allowed ‘the freedom of discovery’ without ‘the obtuseness of explicit exposition.’

However, it’s when we come to Henning Mankell’s Kurt Wallander that I find myself in difficulty. I know I have yet to produce a post about Henning Mankell’s famously non-heroic Norwegian detective, but after reading Mankell’s introduction to Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s first Martin Beck novel, Roseanna, I decided to go back and re-read a few Wallander mysteries with just that intention. I started with Faceless Killers which proved fairly entertaining, but disappointing compared to the Martin Beck novels, more-so when I realized that my dissatisfaction largely stemmed from Mankell’s rather extensive use of exposition, particularly in dealing with backstory.

Next I tried The Dogs of Riga, which I found confused and uncomfortably unbelievable. To me, it read like an unsatisfactory attempt to match Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s The Man Who Went Up in Smoke. What’s worse, I found Kurt Wallander disturbingly hard to like, which so contradicts my first reading experiences.

I do recall practically ‘devouring’ the Wallander novels as they appeared in translation, so I’m not sure what’s changed, but I suspect it’s partly to do with what I’ve been talking about here. Or maybe the Wallander on the page doesn’t live up to Kenneth Branagh’s Wallander on the screen.

I recognize that Mankell had huge agendas for each his books, and since they’ve become immensely popular, he’s obviously onto something, but then, so is Dan Brown… but if I start comparing those two I’ll be getting into a whole other discussion… and probably a bunch of trouble, too. I can only guess that perhaps my tastes have changed dramatically over the years, or maybe I’ll just have to lay the blame on writers such as Sjöwall and Wahlöö for opening my eyes to another a level of excellence.

‘Nite now.

Revised 22/Nov/2013

p.s. – I’ve resolved to give Wallander another go. As soon as I’ve worked my way through the current stack: a trio of Fred Vargas’ Commissaire Adamsberg books, Liz Hand’s two Cass Neary books, and the last three Quirke mysteries by Benjamin Black, I’ll pick up one of the later Wallander books and hopefully revive my lost admiration.

p.s. – I’ve resolved to give Wallander another go. As soon as I’ve worked my way through the current stack: a trio of Fred Vargas’ Commissaire Adamsberg books, Liz Hand’s two Cass Neary books, and the last three Quirke mysteries by Benjamin Black, I’ll pick up one of the later Wallander books and hopefully revive my lost admiration.

No comments:

Post a Comment