|

| Dorothy B. Hugues, 1923 |

Queen of noir: The mysteries of Dorothy B. Hughes

Molly Boyle

Sep 9, 2016

Fiesta. The time of celebration, of release from gloom, from the specter of evil. But under celebration was evil; the feast was rooted in blood, in the Spanish conquering of the Indian. It was a memory of death and destruction. ... A memory of peace, but before peace, death and destruction. Indian, Spaniard, Gringo; the outsider, the paler face. One in Fiesta.”

— Dorothy B. Hughes, Ride the Pink Horse

Mystery writer and Santa Fe resident Dorothy B. Hughes, whose 1946 novel Ride the Pink Horse is among a handful of books she set here, seems to have harbored complicated feelings about the city. Ride the Pink Horse, which is rife with details about Santa Fe’s complex history, centers on a Chicago hoodlum named Sailor who tracks a vacationing Illinois senator to the Plaza during Fiesta. Sailor initially sneers at the small town (which he repeatedly calls a “dump”), its diverse citizenry, and especially its strange rituals — the burning of Zozobra, Fiesta’s garish carnival ambience — even as he enlists the guidance of a Hispano-Indian carousel operator and an enigmatic San Ildefonso Pueblo teenager. Through the course of the novel, as the capital city’s traditions make an impression on Sailor’s callous modernity, Santa Fe itself becomes a kind of phantom character. One wonders what, exactly, the book’s author may have felt about the annual celebration of Fiesta — or even about the town as a whole.

“She hated Santa Fe. She was from Kansas City, which was a bigger place,” said Suzy Sarna, Hughes’ youngest daughter. “I think she thought Santa Fe was beneath her. She didn’t like that it snowed, it was hot in the summer, it was dry. But she lived there for a long time.”

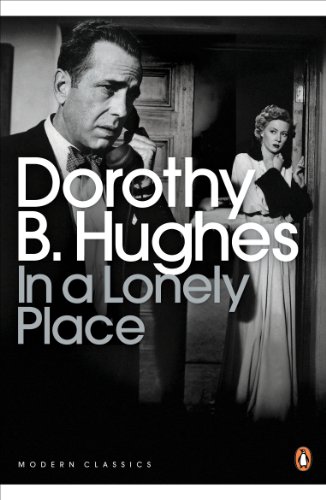

In addition to her cult-hero status among fans of dark midcentury crime fiction, Hughes’ name may ring bells for cinephiles — two notable films are adapted from her books: Ride the Pink Horse (1947), directed by and starring Robert Montgomery, and In a Lonely Place (1950), directed by Nicholas Ray and featuring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame. “It seems like she’s perennially ripe for rediscovery,” says film historian Imogen Sara Smith in the commentary for the Criterion Collection’s 2015 DVD of Ride the Pink Horse. “Periodically some of her books are reprinted, and people write about them and say, ‘Why is she not better known?’ She’s very interested in the relationship between characters and their environments. She’s very interested in class and race and what things like class envy and intolerance do to people’s inner lives and their moral development.”

Hughes' prose wasn't flashy but contained multiple layers. She wrote in a tough, no-nonsense style, about the world as it was, not as we wanted in to be. — editor Sarah Weinman

Hughes’ preoccupations are part of a larger milieu of crime fiction writers who examined complex issues of identity. In a July/August 2016 Atlantic Monthly article on women crime novelists, Terrence Rafferty notes that “while male pulp writers were playing with guns and fighting off those wily femmes fatales, women like [Patricia] Highsmith and Dorothy B. Hughes and Margaret Millar were burrowing into the enigmas of identity and the killing stresses of everyday life.” Sarah Weinman, editor of the Library of America’s Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s and ’50s (2015), writes that Hughes’ “main characters stood outside ruling classes and governments, took part in clandestine operations trying to unseat evil, and overcame damaged pasts and terror-filled presents with resilience and toughness that surprised even them. Hughes, in other words, plumbed three-dimensional depths, no matter the plot device or twist.”

Weinman’s praise for Hughes knows no bounds: She has called her “the world’s finest female noir writer.” She’s not alone: In 1945, critic Howard Haycraft wrote in The New York Times that of all the authors in the mystery genre, “for distinction and influence in their chosen field,” he would nominate only two American writers from the years 1939-45: Raymond Chandler and Dorothy B. Hughes.

Born in 1904, Dorothy Belle Flanagan arrived in the Land of Enchantment in the early 1930s for graduate studies at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. She had already acquired a journalism degree from the University of Missouri, attended Columbia University for a time, and managed to win the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition with a book of poems called Dark Certainty (1931). In 1932 she married Levi Allan Hughes Jr., the scion of a prominent Santa Fe businessman. The couple settled in the city as Dorothy began raising a family — Sarna, born in 1940, was the youngest of three children — and churning out crime fiction. Her first novel, The So Blue Marble (1940), featuring a pair of villainous twin brothers, kicked off a prolific seven-year period during which she published 11 books.

Dorothy enjoyed a privileged life as the daughter-in-law of Levi Allan Hughes, Sr., a wool baron who co-founded Santa Fe Builders Supply Company — Sanbusco — in 1882 and served as president of the First National Bank. (A Randall Davey portrait of him still hangs in the bank on Lincoln Avenue today.) The Hughes’ former estate at 215 Washington Avenue was grand, Sarna remembered. “That house was huge. It took up a whole block. We had a swimming pool, a tennis court, gardens, all kinds of stuff. It was paradise there.”

Sarna described her relatives in a phone call from her home in Washington State. “We have a fascinating family. My grandfather [Hughes, Sr.] came to New Mexico from Bloomington, Indiana. Sanbusco was what he created. Betty Zook [of the family who owned Zook’s Pharmacy, which closed in 1983 and was the oldest New Mexico pharmacy in continuous operation] married my uncle Frank Flanagan. My aunt Calla [Dorothy’s sister] was Calla Hay of The New Mexican. Everybody knew Calla — she wrote [a column called] Paso Por Aquí. I worked at Sanbusco for a while … We all worked there at one time or another.”

Dorothy Hughes seems to have maintained an active social life in town. A July 1938 Santa Fe New Mexican write-up of the musical revue Tourists Ahoy! at the Lensic lists Hughes and Hay as co-directors of a production that starred Jane Baumann, wife of artist Gustave Baumann, and featured original songs by Hughes. In 1940, she began reviewing mystery novels for the Albuquerque Tribune. But she was most devoted to her fiction, often writing late into the night after her children had gone to bed. Describing her writing process, Hughes said, “You learn from newspaper writing, and you learn where to cut a story. Then you have to read writers in the field of fiction of which you are interested.” Sarna remembered her mother’s iron will not to be disturbed: “You did not go into her room when she was writing. She wrote in her bedroom laying in bed, and you had to knock on the door, and if she was busy, you couldn’t go in. She would just not answer.”

She was busy cooking up thrillers — “Writing was a compulsion for me,” she told The New Mexican in 1978. Her first novel set in Santa Fe, The Blackbirder (1943), is a fast-paced tale of wartime espionage featuring a strong-willed, desperate young woman named Julie Guille, who travels by train from New York to Santa Fe, on the run from both the Gestapo and the FBI, who are pursuing her because of her family’s entangled alliances. Julie has heard tales of the Blackbirder, a clandestine trafficker who ferries refugees from Santa Fe to Mexico, so she holes up in a room at La Fonda to wait for word of the mysterious man. Hughes’ resourceful heroine prizes self-preservation at all costs, at one point hiding out among a family of Tesuque Pueblo Indians and disguising herself as a member of their clan in order to avoid discovery by her enemies. A note in the 2004 Feminist Press reissue of the novel states that Hughes’ protagonist stands in stark “contrast to the typical representations of wartime women as ‘Mrs. Minivers’ guarding home and hearth.”

Hughes mined her adopted hometown for details that she deposited into her books. Ride the Pink Horse’s title refers to Tío Vivo, the Taos carousel that once graced the Plaza during Fiesta (it is also featured in the film, along with footage of an actual Zozobra and Fiesta). Sarna said, “She had a great memory for things, like with Tío Vivo. I rode and rode and rode on Tío Vivo. … It was a hand-cranked merry-go-round, and if he [the ride operator] liked you, he’d let you go on and on.” This exact scenario marks a pivotal moment in the novel, when Sailor seems to soften at the ride operator’s display of generosity, coupled with the childlike joy of the Pueblo teen who gets to ride the carousel’s pink horse once more.

Both Ride the Pink Horse and The Blackbirder feature several scenes set at La Fonda, whose ’40s incarnation, complete with an atrium dining room, is the center of the action for well-heeled visitors and their schemes. The hotel seems to have been integral to the Hughes family, too. According to Sarna, “We always went and had dinner or lunch there. Any time we needed to find my dad, he was in La Fonda. La Fonda was the place you went to if you wanted to find anyone, or just have dinner, or if you wanted to hang out.”

Before long, Hollywood came calling for Dorothy Hughes, first adapting The Fallen Sparrow (1942) into a Richard Wallace-directed film starring John Garfield. In 1944, the Hughes family moved to Los Angeles. “She was offered a job at the studios writing scripts,” said Sarna. “That’s when we moved to California.” Sarna said her mother thrived in LA. “She liked being at the beach. She’d go to the studio, do her thing. She was much happier in California.”

The family’s roots remained in the Southwest, however. “Every summer we went back to Santa Fe. We always went in the summertime.” An August 1944 column in The New Mexican contains a breathless account of Hughes’ recent meeting with Alfred Hitchcock, after the head of the story department at Selznick Pictures, Margaret McDonell, asked Hughes if she’d like to go to the set of Hitchcock’s movie The House of Doctor Edwards [which later became Spellbound], starring Ingrid Bergman.

Hughes’ presence on the set of Spellbound marked a lucky twist of fate — there, she met Bergman, who is said to have clued Humphrey Bogart in to Hughes’ genius, the result being that Bogart bought the movie rights to Hughes’ 1947 Los Angeles-set novel In a Lonely Place. The most famous of Hughes’ film adaptations, Nicholas Ray’s noir is a moody tour-de-force that features virtuoso performances from Bogart and, especially, Gloria Grahame.

The novel In a Lonely Place — which, like Ride the Pink Horse, has a markedly different plot from that of the film — is one of Hughes’ finest and most experimental thrillers. It employs the unreliable narration of screenwriter Dix Steele, who may or may not be a serial killer of young women, allowing the reader to uncover Steele’s darkest depths with the assistance of two indelible female characters, his upstairs neighbor and his friend’s wife. Weinman told Pasatiempo, “Hughes was singularly able to create terror and suspense in a way that generated palpable fear. She was so good with character — I still think of Dix and Laurel and Brub and Joan of Lonely Place. ... Her prose wasn’t flashy but conveyed multiple layers. She wrote in a tough, no-nonsense style, about the world as it was, not as we wanted it to be.”

Hughes returned to Santa Fe for a time in the early 1960s after her mother died, having taken an extended break from writing crime fiction, though she continued penning book reviews for several newspapers, including the Albuquerque Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Herald-Tribune. In 1963, she published The Expendable Man (reissued in 2012 by the New York Review of Books), which focuses on a black medical student who is accused of murdering a young white girl in Phoenix. The novel has a remarkable twist — the reader is not clued in to the character’s racial identity until about 50 pages in, when, as Weinman said, “it becomes stunningly clear why he is being treated unfairly by police and why he may have reason to fear.” In the NYRB edition’s afterword, novelist Walter Mosley writes of Hughes, “Her work belongs in our canon of classic American stories. Bringing her back is no act of nostalgia; it is a gateway through which we might access her particular view of that road between our glittering versions of American life and the darker reality that waits at the end of the ride.”

Though Hughes favored progressive characters and storylines, her affiliations are murky. When asked if her mother was a feminist, given that her titles have been reprinted by The Feminist Press and Persephone Books in the UK, Sarna said, “I never thought of her that way. She was the boss of the world.” Sarna added that her mother was certainly “very liberal,” though Weinman said that Hughes “actively disdained second-wave feminism, putting it down in interviews.”

Nonetheless, Hughes tended to create iconoclastic female characters at a time when many of her peers did not, and she was obviously also drawn to racially complex narratives. Sailor, the xenophobe of Ride the Pink Horse, frequently uses the word “spic,” and casually dubs the carousel operator “Pancho Villa.” But the selflessness of the novel’s Hispanic and Indian characters seems to spark a kinder, gentler awakening for Sailor. One commentary on Hughes’ minority characters, published in the literary journal Melus in 1984 by Laurence J. Oliver Jr., is titled “The Dark-Skinned ‘Angels’ of Dorothy B. Hughes’s Thrillers,” highlighting her tendency to make the black, Native, or Hispanic people in her novels morally superior to the rest.

Weinman said she viewed Hughes’ intentions with these characterizations to be well-meaning, if sometimes hackneyed. “I think Hughes was trying to do the right thing. She turned down the opportunity to blurb Patricia Highsmith’s A Game for the Living because she abhorred the Mexican stereotypes. But I also think she had a knack for not always realizing what was in her text. … She wanted to engage in writing about race in as well-rounded a way as was capable to her at the time, but her attitudes, to a 21st-century audience, would be subject to a lot more scrutiny and criticism.”

Despite Sarna’s maintaining that her mother disliked the town, Weinman said that judging from her fiction, “there is a sense that her heart belonged to Santa Fe.” After her husband’s death in 1975, she returned several times over the years (Calla Hay remained here, as did other relatives). After she died in Ashland, Oregon, in 1993, her ashes were interred at Santa Fe’s Rosario Cemetery. There, near the graves of the Sisters of Loretto, Dorothy Hughes’ stone sits alone. She is not buried with the rest of the Hughes family, who are all two miles away at Fairview Cemetery. When asked why her mother was laid to rest in the town she supposedly loathed, Sarna said, “She loved my dad. … We’re all buried there. I will be buried there.”

Today, traces of Dorothy B. Hughes around town are few. The house at 215 Washington Avenue is for sale now, its left side covered by a creeping swath of dark-green ivy that climbs to its second floor. Standing in front of the once-grand residence of one of Santa Fe’s finest — and most forgotten — writers, a vivid picture comes to mind. Once upon a time, a hard-nosed dame with an overactive imagination likely reclined behind one of these shadowy upstairs windows, writing something dastardly in longhand on her bed, ignoring every knock at the door.

No comments:

Post a Comment