Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo’s Martin Beck

By

Is Martin Beck the original moody sleuth?

Is Martin Beck the original moody sleuth?

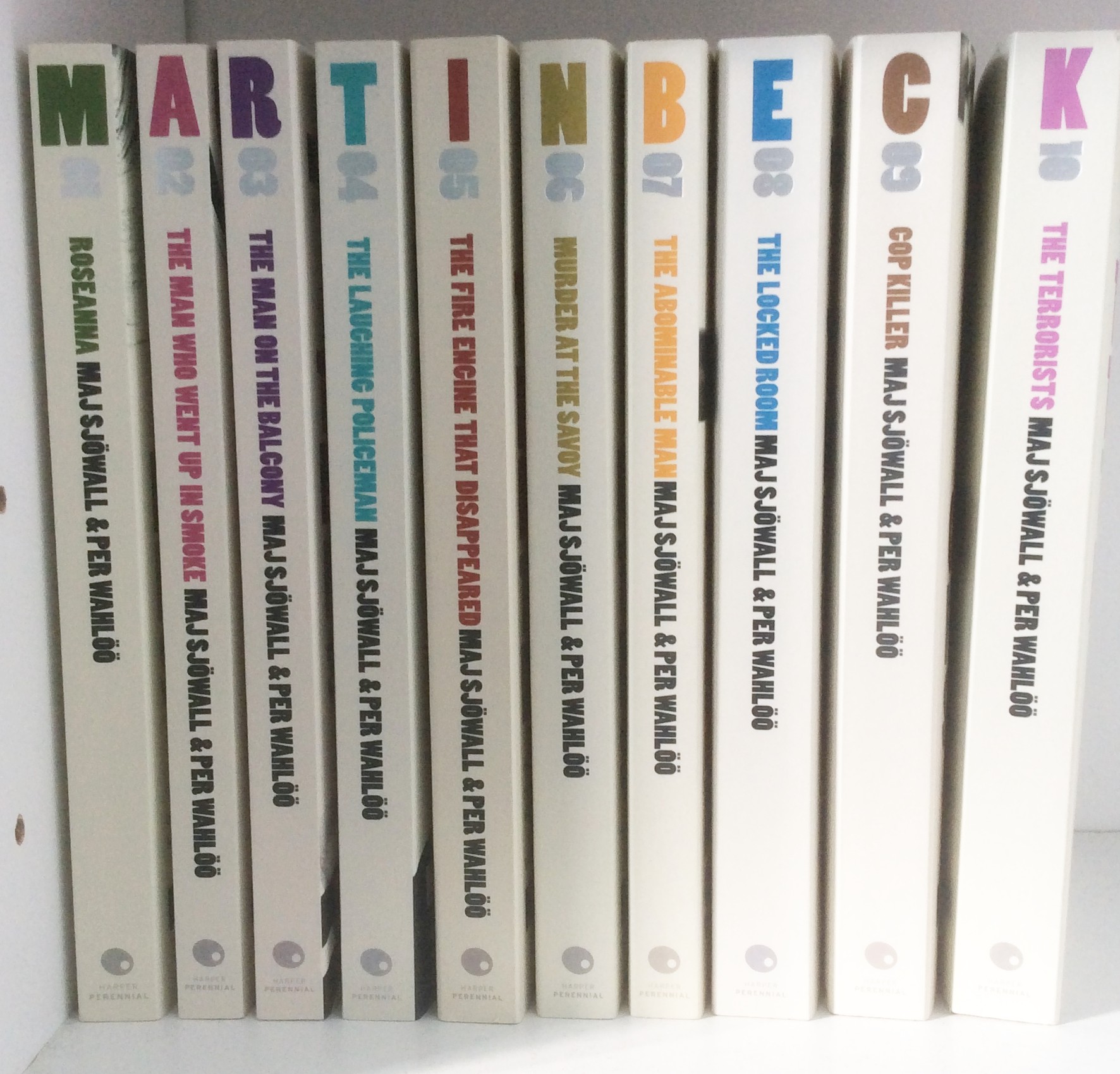

I ended my last full post (September 4, 2013) saying I’d finally begun reading Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s Martin Beck novels, though I don’t rightly know how I managed to cultivate such a passion for ‘moody sleuths’ without coming across Martin Beck much sooner, especially since so many crime fiction writers count this ten book series as being ‘the’ most influential in shaping the modern mystery novel, particularly the police procedural.

I should be red-faced, I know… but in the past month I trust I’ve made amends; I’ve read all ten, and will undoubtedly read them again in the future. They’re that good!

As I said in my earlier post, Swedish journalists, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, co-wrote the Martin Beck series, first published between 1965 and 1975. The couple set out to use the police procedural to carry a penetrating critique of Sweden’s social and political conditions at the time.

If you’ve read my initial post on Greek writer Petros Markaris’s Inspector Costas Haritos

series you may recall that I was excited to learn that Markaris’s primary objective in turning to writing mysteries was to explore the social and political realities of his country while keeping within the genre of the crime novel. I was just as elated to learn that Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s Martin Beck novels promised the same for 60s-70s Sweden, along with adding another ‘moody sleuth’ to my list.

series you may recall that I was excited to learn that Markaris’s primary objective in turning to writing mysteries was to explore the social and political realities of his country while keeping within the genre of the crime novel. I was just as elated to learn that Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s Martin Beck novels promised the same for 60s-70s Sweden, along with adding another ‘moody sleuth’ to my list.

Ten Years, Ten Books

An article from a 2009 issue of The Guardian online gives an intriguing picture of Sjöwall and Wahlöö as a couple who sat down every evening after their children had gone to bed, and wrote:

“Ten years, 10 books. Each book 30 chapters, 300 chapters in all. Every one centred on the same group of middle-aged, mostly unprepossessing policemen in Stockholm’s National Homicide Department. Often, very little happens. Sometimes for pages on end. What is more, each book is a Marxist critique of society. Their mission – or “the project” as the authors call it – is to hold up a mirror to social problems in 1960s Sweden.Unlikely as it may sound, the books have become international bestsellers, over 10m copies sold and counting. Classics of the thriller genre, they’ve been made into films and adapted for television. Subsequent generations of crime writers are fans. There’s no doubt that the latest left-leaning Swedish author to hit the bestseller lists, Stieg Larsson, would have read them. Some say the couple wrote the finest crime series ever; that without them we would not have Ian Rankin’s John Rebus or Henning Mankell’s Kurt Wallander.”

Because so much has been written about Sjöwall and Wahlöö and the Martin Beck novels, I won’t go on about what’s readily available via Google. Goodreads, and any number of fine book review blogs. Instead, since for me it’s always about the ‘moody sleuth’, I thought I’d take a look at Martin Beck in each of the ten titles, with reference to the introduction to each re-released Vintage Crime/Black Lizard edition. (I’m including a link to each title’s Amazon page so that you can read these excellent introductions in the Kindle versions.)

Roseanna, first of the Martin Beck novels

The introduction is by Henning Mankell, author of the series featuring another moody sleuth, Kurt Wallander. Mankell writes:

“I can’t even count how many times I’ve been asked what Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s books have meant to me. I think that anyone who writes about crime as a reflection of society has been inspired to a certain extent by what they wrote. They broke with the previous trends in crime fiction. … Of particular importance was the fact that Sjowall and Wahloo broke with the hopelessly stereotyped character descriptions that were so prevalent.”

As to ‘hopelessly stereotyped character descriptions’, Mankell mentions that the British-style detective novel was “the dominant form” in Sweden prior to the publication of Roseanna, and refers to popular Swedish writer Stieg Trentor, described as one of Sweden’s “Agatha Christies” (according to Wickipedia)… so I’m assuming the norm was a form of ‘cozy’ mystery, which Wiki explains: “virtually never dwell on sexuality or violence, or employ any but the mildest profanity. The murders take place off stage, and frequently involve relatively bloodless methods such as poisoning and falls from great heights. The wounds inflicted on the victim are never dwelt on, and seldom used as clues. Sexual activity, even between married characters, is only ever gently implied and never directly addressed, and the subject is frequently avoided altogether.”

After reading the Martin Beck novels, which depict ‘real’ crimes in plain, un-mitigated language, I can understand why this lot created such a stir.

In his introduction to Roseanna, Mankell also mentions Swedish writer, Maria Lang, another of Sweden’s “Agatha Christies”. An informative piece by Petri Liukkonen and Ari Pesonen corroborates Mankell’s assesment:

“[Lang’s] works are rooted more or less in the British tradition of whodunnits, although she took her subjects from hidden family secrets and conflicts, incest, and other sexual traumas. Sex was an essential part of stories in the hard-boiled fiction, but it was not common in cozy mysteries, and Lang’s books were considered daring. The methods of murder are various and ingenuous but relatively bloodless”.

I imagine that the transition from the likes of Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, and even Maria Lang’s more risqué characters, to the fallible non-hero-warts-and-all characters in Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s Martin Beck novels might have proved startlingly uncomfortable to many readers, though exhilarating to others, particularly aspiring mystery writers.

Martin Beck and his police cohorts are anything but stereotypical; for one thing, they work as a team, most of the individuals as moody as Beck himself.

An exceptionally well-written piece in the LA Review of Books, August 5th, 2011 speaks at length about how the police procedural

“perfectly supported [Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s] interest in investigating systemic, rather than individual, dysfunction… deriving its suspense not from whodunit, but from why they did it and how they will get caught…Instead of following the ratiocinative exploits of a single great detective, the procedural disperses our attention across the members of a crime-fighting unit. Modern detection is not just a team effort; it is also a highly bureaucratic one. Sjöwall and Wahlöö are keenly aware of this convention and use it to full effect.Although their lead character, Inspector Martin Beck (eventually chief of Sweden’s National Homicide Squad), is at the heart of The Story, he remains a somewhat remote and enigmatic figure. Phlegmatic, taciturn, introverted, Beck provides the occasion but not the voice for Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s political critique; indeed, Beck “always [tries] to avoid conversations of political import” (The Locked Room, 1972).Beck is a police officer, not a crusader, and the men he leads are similarly uninspiring:[Beck] disliked Gunvald Larsson and had no high opinion of Ronn. He had no high opinion of himself either for that matter. Kollberg made out he was scared and Hammar had seemed irritated. They were all very tired, added to which Ronn had a cold. (The Man on the Balcony, 1967)Their idiosyncrasies and failings are reiterated across the series with affectionate consistency and touches of the authors’ characteristic dry wit.

Melander, for example,

“was generally known for his logical mind, his excellent memory and immovable calm. Within a smaller circle, he was most famous for his remarkable capacity for always being in the toilet when anyone wanted to get hold of him. His sense of humor was not nonexistent, but very modest; he was parsimonious and dull and never had brilliant ideas or sudden inspiration. Briefly, he was a first-class policeman. (The Fire Engine That Disappeared, 1969)

Roseanna – a brief overview:

The nude, strangled body of a young woman is dredged from Sweden’s Lake Vattern. Martin Beck and his team are called in when the local police are unable to discover the victim’s identity, but three months later, after extensive and very thorough police work, all the investigators know is that her name was Roseanna and she was last seen alive on a cruise boat carrying eighty-five possible, but unlikely suspects.

Martin Beck is no solitary hero

The lengthy investigation demonstrates the reality of drawn-out stretches of time where police work produces no useful results; though it sounds excruciatingly tedious, it lends a heightened sense of reality that underlines the dogged persistence of police procedure.

We get to know Martin Beck and the members of his team during this relatively unproductive period, through snippets of conversation between characters, via their thoughts and actions, and through what others say or think about them. Within the details of the policemen’s quiet diligence are instances of interaction, snippets of insight and wry humour that allow us to see the characters and their relationships to one-another more clearly. For example, early in the investigation, Martin Beck visits the spot where the victim’s body was recovered:

“One hundred and fifty feet beyond the jetty, the dredger’s bucket clanged and clattered under the watchful eye of some seagulls who were flying in wide, low circles. Their heads moved from one side to the other as they waited for whatever the bucket might bring up from the bottom. Their powers of observation and their patience were admirable, as was their staying power and optimism. They reminded Martin Beck of Kollberg and Melander.”

We meet Beck, Lennart Kollberg, and Melander in Roseanna, and get to know more of the men and women in his milieu as the series progresses. Some are more likeable than others, but I found myself warming to almost all of them before the end, though Sjowall and Wahloo do paint Beck’s superiors in a rather relentlessly negative light, which of course suits their agenda.

Martin Beck is a moody sleuth and he doesn’t feel well

Coming back to Henning Mankell’s introduction to Roseanna, he points to Martin Beck’s less than robust constitution as an example of ‘breaking with stereotypes’:

I haven’t counted how many times Martin Beck feels sick in Roseanna, but it happens a lot. He can’t eat breakfast because he doesn’t feel good. Cigarettes and train rides make him sick. His personal life also makes him ill. In Roseanna the homicide investigators emerge as ordinary human beings. There is nothing heroic about them. They do their job, and they get sick. I no longer remember how I reacted forty years ago, but I think it was a revelation to see such real people as police officers in Roseanna.

More than two months into the investigation, Martin Beck catches a cold:

After lunch Martin Beck felt that the lymph glands in his neck were beginning to swell and by the time he got home that evening it was hard for him to swallow.

Despite his wife’s insistence that he stay home, Beck returns to work the next morning.

Martin Beck felt anything but well. He had a cold, and a sore throat, his ears hurt him and his chest felt miserable. The cold had, according to schedule, entered its worst phase. Even so, he had deliberately defied both the cold and the home front by spending the day in his office. First of all he had fled from the suffocating care which would have enveloped him had he remained in bed. Since the children had begun to grow up, Martin Beck’s wife had adopted the role of home nurse with bubbling eagerness and almost manic determination. For her, his repeated bouts of colds and flu were on a par with birthdays and major holidays.

Martin Beck suffers from motion sickness, smokes too much and drinks far too much coffee (which plays hell with his stomach). He has an aversion to crowds, has long ago fallen out of love with his wife, and feels guilty that he has little to do with his two children.

Yes, he’s a moody sleuth, and as the previously mentioned article from the Guardian so aptly puts it:

“He may be empathetic and dogged but mostly he’s dour, humourless, dyspeptic, antisocial. When Sjöwall and Wahlöö invented him, the idea that a crime novel should feature a credible detective, flaws and all, was new. We’ve grown so used to our curmudgeonly fictional coppers, whether in books or on screen, that it’s easy to forget that Beck is the prototype for practically every portrayal of a policeman ever since, in this country, or America, or continental Europe.”

As one or two of you may have noticed, this is a revised and extended version of the post I contributed last Tuesday (14 Oct 2013), but I didn’t feel I’d done justice to Sjowall and Wahloo’s impressive series. Hence the rewrite.

Also, my stated intent was to ‘take a look at’ all ten of the Martin Beck novels while referring to commentary in the introductions by prominent writers heading each of the re-issued Vintage Crime/Black Lizard editions. I realize my plan was overly ambitious, particularly since I prefer not to stray too far from concentrating on the ‘moody sleuths’ in whatever book I’m talking about at the time. Instead, I’ll focus on two, possibly three of the titles, most likely referring to some of the others where pertinent. We’ll see how that goes.

In closing I want to comment on the idea of how ‘ground-breaking’ the police procedurals of Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö were for readers of their time. Reading Roseanna or any of the Martin Beck novels with “our twenty-first-century eyes” (thanks, Val McDermid), it’s difficult to imagine how revolutionary it would have seemed to readers in 1965. This reminds me of sitting in a film studies class watching Citizen Kane and trying to imagine how viewers in 1941 would have reacted to revolutionary filming techniques, varied camera angles and unconventional lighting techniques… techniques now so ordinary we don’t even notice them in present day film.

Honestly, the only thing I can liken it to is my first experience of watching a 3D film; probably not nearly as dramatic, but an eye-opener, for sure.

G’night now.

No comments:

Post a Comment