Vargas Llosa breaks his silence over friendship with García Márquez

Nobel laureate discusses ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ at Spanish open university course in Madrid

Javier Rodríguez Marcos

San Lorenzo De El Escorial, July 12, 2017

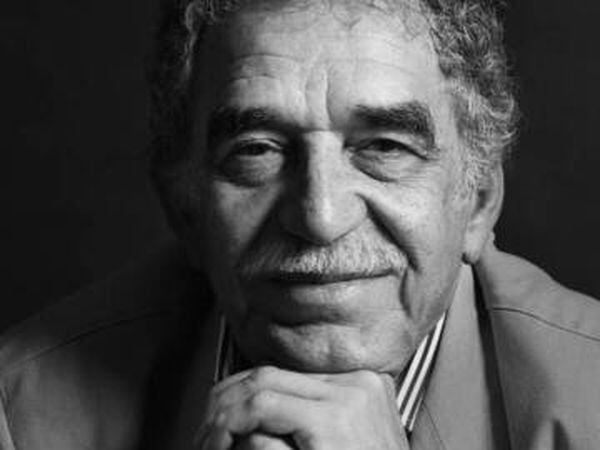

In 1967, the year One Hundred Years of Solitude was published, its author, Gabriel García Márquez, met fellow Latin American writer Mario Vargas Llosa and the two became firm friends. But nine years later, the pair would famously fall out, reportedly never to speak again.

Last Thursday, Vargas Llosa broke a long-standing silence and spoke of his relationship with Márquez, who died in 2014, as part of a series of lectures to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

The 81-year-old Nobel laureate described the man he called “Gabo” to his audience at the San Lorenzo de El Escorial summer school, organized by Madrid’s Complutense University, depicting him as shy and unsociable in public but very funny and entertaining in private.

The pair came from similarly disjointed family backgrounds: both were brought up by their grandmothers and did not get on with their fathers. But what really connected them, said Vargas Llosa, was their love of the work of 20th-century US writer William Faulkner, “our common denominator.” Equally important, said Vargas Llosa, was that they both came to the full realization that they were Latin Americans when they first came to Europe.

Vargas Llosa soon brought up what he called the political event that awoke “the world’s curiosity for Latin America and its literature,” and which would lead to his falling-out with García Márquez: Cuba. “I was very enthusiastic about the revolution at first; García Márquez hardly at all. He was always very discreet about it, because he had been purged from the Communist Party when he worked for Prensa Latina,” which was the official news agency of Cuba, founded shortly after the revolution that ended in 1959.

But later, García Márquez would be photographed alongside Fidel Castro. “I think he was a very practical man and realized it was better to be with Cuba than against it. He managed to avoid the mud that was slung at those of us who were critical of the way the revolution evolved toward communism from its early position, which was more liberal and socialist.”

Describing One Hundred Years of Solitude, Vargas Llosa said he was “stunned” by the book when he read it. “So much so that I hurried off to write an article called El Amadis en America [Amadís de Gaula was a popular Spanish chivalric romance referenced by Miguel de Cervantes in Don Quixote]. I thought that at last Latin America had its own novel about knights, a story where the imaginary came to the fore without losing the underlying substance of reality. It also had the virtue of few masterpieces: the ability to attract a demanding reader concerned about language, and at the same time a basic reader only interested in following the story.”

Vargas Llosa also taught García Márquez’s work at universities in Puerto Rico, the United Kingdom and Spain in the late 1960s, which led to his 1971 book García Márquez: Story of a Deicide, based on his doctoral thesis.

In contrast to One Hundred Years of Solitude, Vargas Llosa said he thought García Márquez’s weakest book was 1975’s The Autumn of the Patriarch, which he described as “a caricature of García Márquez, a novel by somebody imitating himself.”

Vargas Llosa included García Márquez alongside other Latin American writers like the Mexican Juan Rulfo and Cuba’s Alejo Carpentier in terms of knowing how to find beauty in the “ugliness” and “underdevelopment” of Latin America. Asked if a prosperous Latin America would produce such imaginative literature as that of the three writers he mentioned, Vargas Llosa said he was unsure, but added: “I wouldn’t want our continent to stay as it is so it can produce great literature. Countries get the literature they deserve.”

Inevitably, Vargas was asked whether he and García Márquez ever saw each other again after the infamous incident outside a cinema in Mexico City when the former punched the latter in the face during their argument about Cuba. “No,” he replied, smiling broadly, then added: “We’re moving toward dangerous ground. The time has come to put an end to this conversation. I was sad when he died, it was like the death of [Argentinean novelist Julio] Cortázar or [Mexican writer] Carlos Fuentes. They weren’t just great writers, but also great friends. To discover that I am the last of that generation is sad.”

No comments:

Post a Comment