|

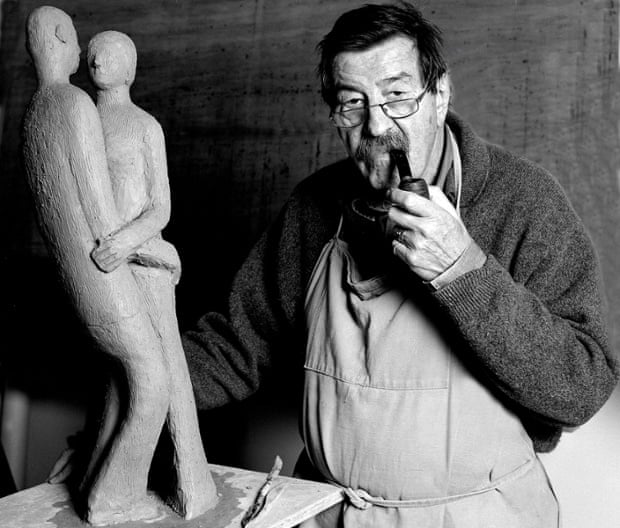

| Self-portrait Günter Grass |

Günter Grass obituary

Nobel-winning German author who arrived on the literary scene in 1959 with the bestselling novel The Tin Drum

Jonathan Steele

Monday 13 April 2015 13.57 BST

Günter Grass, who has died aged 87, was Germany’s best-known postwar novelist, a man of titanic energy and zest who, besides his fiction-writing, enjoyed the cut and thrust of political debate and relaxed by drawing, painting and making sculptures. Bursting on to the literary scene with his bestselling novel The Tin Drum in 1959, Grass spent his life reminding his compatriots of the darkest time in their history, the crimes of the Nazi period, as well as challenging them on the triumphalism of unification in 1990, which he described as the annexation of East Germany by West Germany in which many citizens became victims.

He was always controversial, and sometimes bitterly attacked by critics at home for discussing German victimhood as well as German guilt. Outside his country he was, inevitably, called Germany’s postwar conscience, a label he shared with the older writer Heinrich Böll. In 1999, much later than expected, he won the Nobel prize for literature. The Scandinavian judges praised his “creative irreverence” and “cheerful destructiveness”.

Seven years later, he stunned critics as well as admirers by admitting in the autobiographical Peeling the Onion that at the age of 17 he had been drafted into the notorious Waffen-SS in the last few months of the second world war. Some claimed that he had revealed his long-held secret for cynical reasons to boost book sales, or that he had suppressed it for so long to avoid jeopardising his chances of winning the Nobel. Christopher Hitchens denounced Grass as “something of a bigmouth and a fraud, and also something of a hypocrite”. The former Polish president and Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa said he was glad he had never met Grass, and urged him to give up his honorary citizenship of Gdańsk, the town where he was born and whose Nazi-era troubles were portrayed in The Tin Drum. Wałęsa later retracted his remarks.

Grass’s adolescence of unthinking patriotism was well known before Peeling the Onion. His father, Wilhelm, was German, and his mother, Helene (nee Knoff) was Polish, and they ran a grocer’s shop in Gdańsk (then the interwar free city of Danzig). Günter joined the Hitler Youth: his political awakening came later, when, after the war, he worked in potash mines and as a stonemason’s apprentice, rubbing shoulders with ex-Nazis and ex-communists. He decided scepticism and moderation were better than ideological extremes, a position he maintained throughout his life.

As a young man, Grass studied painting and sculpture in Düsseldorf and Berlin. He was also a jazz drummer and a poet. But it was The Tin Drum that catapulted him to fame. The book was a biting attack on nazism and the German mentality from which it arose. Eva Figes, the writer who came to Britain on the eve of the war as a Jewish child refugee from Berlin, said she knew immediately that The Tin Drum “was the book the postwar generation was waiting for. It coped with the tragedy of the Third Reich with huge energy and scope. It was inventive, macabre, funny and tremendously important.” The Nobel prize committee said its “frolicsome black fables portray the forgotten face of history”.

The book’s hero and narrator is Oskar Matzerath, a boy who was born with an adult’s ability to think and feel, but who decided never to grow tall. He recounts his life story while in a mental hospital. It covers numerous love affairs as well as the politics of the war, the Red Army’s invasion of Danzig in 1945, the expulsion of the German population, and West Germany’s postwar years. The dwarf’s weapons are a shriek that can break glass and a tin drum he received on his third birthday. He threatens to use violence if anyone tries to remove it. In one extraordinary scene he hides under the platform at a Nazi rally and subverts the marching band by drumming out an Austrian waltz rhythm that the players cannot resist taking up.

The book’s imaginative boldness and wild satirical style were as remarkable as its subject matter. It ended with Oskar’s nightmare vision of a black witch: “She had always been there, even in the woodruff fizz powder [used to make a soda pop substitute], bubbling so green and innocent; she was in clothes cupboards, in every clothes cupboard I ever sat in … it’s her shadow that has multiplied and is following the sweetness. All words: blessed, sorrowful, full of grace, virgin of virgins … Later on four tomcats, one of whom was called Bismarck, the wall that had to be freshly whitewashed, the Poles in the exaltation of death, the special communiques, who sank what when, potatoes tumbling down from the scales, boxes tapered at the foot end, cemeteries I stood in, flags I knelt on, coconut fibres I lay on … the puppies mixed in the concrete, the onion juice that draws tears, the ring on the finger and the cow that licked me … Don’t ask Oskar who she is! Words fail me. First she was behind me, later she kissed my hump, but now, now and for ever, she is in front of me, coming closer.”

The Tin Drum was made into a film almost 20 years later by the renowned director Volker Schlöndorff. It shared the 1979 Cannes film festival Palme d’Or with Apocalypse Now and won the Oscar for best foreign language film of 1979. Grass wrote two sequels, Cat and Mouse (1961) and Dog Years (1963), both also centred on Danzig and its ethnic complexity. Dog Years touched on the mass expulsion of Germans from Gdańsk at the end of the war, a subject Grass was to cover extensively four decades later in Crabwalk (2002), bringing back one of Dog Years’ characters.

Buoyed by his literary success, Grass went into politics in the 1960s, campaigning regularly for Willy Brandt and the Social Democrats. There were rumours that he might take a government job when Brandt became chancellor, though this was never likely. He dedicated a 1972 account of his political campaigning, entitled From the Diary of a Snail, his metaphor for patient but effective progress, to his children.

His cautious, almost pessimistic, approach to politics sat oddly with his driven personality and his image as a rough diamond on the literary scene. Grass was never an intellectual, and liked being seen as a gadfly. He disdained the politics of the anti-Vietnam 1968 generation, even though its members were fired up, as he was, by the sense that Germans of their parents’ generation should honestly face their Nazi past. Grass abhorred extremism, and he thought the 1968ers were dishonest. They refused to accept that German guilt masked countless individual tragedies. Though complicit in nazism in the broad sense, many Germans became victims in the final year of the war, particularly the millions who were forced out of Danzig and other parts of eastern Europe. Grass’s mother, who was raped by Russian soldiers, was herself part of the refugee tide.

Crabwalk dealt with this facet of Germany’s suppression of history, the many instances of victimhood in the shadow of defeat. Its narrator is a 1968er whose narrow and blinkered style of parenting results in his son becoming a neo-Nazi. The book’s central drama is the sinking, in 1945, by a Russian submarine of the Wilhelm Gustloff, a ship carrying close to 9,000 German refugees, mainly women and children, in the Baltic sea. The catastrophe cost four times as many human lives as the sinking of the Titanic, yet it was barely mentioned in public after the war. Grass’s argument was that all Germans, and particularly the liberal left, must look more sensitively at the issue of victimhood as well as villainy in German history. This was not to minimise the crimes of the Holocaust or to balance one evil with another, but simply because the fact of German suffering is part of the historical reality.

It was not an issue that could have been handled in Germany in the 1950s, let alone the 80s. Even though it had lost much of its bite by the time Grass wrote Crabwalk, it was still a bold book. The fate of this shipload of civilians, along with that of the millions of Vertriebene (expellees) who were forced at gun-point to abandon well-established German communities in Poland and Czechoslovakia, was the biggest neglected story of the second world war and its aftermath.

Grass wanted to break the taboo that meant that although organisations of expellees emerged to plead their case, mainstream Germany, as well as foreign governments, ignored them because their plight cast Germans as victims. Many individual expellees joined in this collective suppression and did not even tell their children what had happened. A film about the Gustloff came out in the 50s but was quickly forgotten. Ironically, the issue died completely after the treaties with Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union that Brandt signed in the early 70s. The better that government-to-government relations became, the harder it was to discuss what had happened to Germans in eastern Europe.

As a leftwinger, Grass could handle the subject sympathetically without being accused of moral equivalence. As the title Crabwalk implies, the book does not approach the issue head-on. Nor is the sinking of the ship the centrepiece either of the narrative or of Grass’s message about suppression. The story is told from the point of view of three generations. The “narrator” is a journalist in his 50s who is urged by his mother, a survivor of the tragedy, to write about the disaster before it gets too late to interview those who were there.

Crabwalk was not the first book by a German author to take up the theme of Germans as victims. WG Sebald’s essay on Air War and Literature, about the horror of the Allies’ carpet-bombing of German cities, had come out in Germany four years earlier. Typically, however, Grass took an issue that had been rising to the surface and gave it an agenda-setting new impetus. He also moved the question of historical amnesia and German victimhood further than earlier writers. Crabwalk discussed the political damage suppression can cause. “In a way you can say the book is too late. But you have the advantage of seeing the story from the point of view of three generations. I wanted to describe this suppression complex and its consequences,” he said.

The book also tried to answer the question of why young Germans, albeit a small minority, could be fascinated by neo-Nazism. One reason, Grass argued, was that the history of the Nazi period was still badly taught in schools and in the German media. “Films tend to portray Nazis as raving idiots. The fact that the Nazi party came to power legally at a time when there were six million unemployed is suppressed,” he said.

Before becoming a troopship, the Wilhelm Gustloff had been run by the Kraft durch Freude (strength through joy) society, which was given the expropriated assets of the trade union movement and throughout the 30s provided heavily subsidised holidays to German workers who had never been abroad before. “You have to explain to young people that this was a ‘classless’ ship. There was a socialist element in nazism, done for propaganda purposes, of course. But it has to be explained,” Grass said, adding that young Germans also needed to be told that in 1938 most European countries, including sections of the governing class in England, admired Hitler as a bulwark against communism.

More controversial, at least within Germany, was Grass’s contribution to the debate on unification, where he found himself criticised, even by social-democratic friends, for romanticism, an unusual charge for a man who called himself a political “snail”. But 1990 was one of those rare moments in history when most people thought speed was the order of the day. For decades, Germans had paid lip service to reunification, never believing it would happen in their lifetimes. When the reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev gave the green light for change and the East German authorities opened the Berlin Wall under pressure from thousands of street protesters, people grabbed at the chance of voting for unity. Grass’s notion of a slow march towards unification by means of the two German states’ first becoming a confederation was unrealistic, his friends said.

By then Grass was too well-known to be cowed. He had become an icon, and was confident enough of his convictions not to worry about political isolation even though he was human enough to be wounded. He wrote a long rambling novel,Too Far Afield (1995), to justify his position. His scepticism about German unity sprang in part from his feeling that East Germans were being given a raw deal. Not that he had any sympathy for the East German regime; in the years before unity he regularly travelled to East Germany to meet dissident writers, his fame making it hard for the communist authorities to bar him. He was one of the first West Germans to visit Poland to try to overcome the bitter legacy of Polish-German relations.

But he found it troubling that after 1990 West Germans were more ruthless in rooting out and sacking everyone who was linked, however loosely, to the East German regime, including schoolteachers and university professors, than they had been with former Nazis half a century earlier. “There was the argument that ‘We don’t want to repeat the mistakes of postwar West Germany.’ So the mistakes of West Germany are put on the backs of East Germans. It’s hypocrisy, and pure anti-communism,” he said. “Erich Honecker [the former East German leader] was put on trial though he had been received with a red carpet in Bonn two years before the Berlin Wall came down. I’m not in favour of Honecker but it was ridiculous. A kind of belated revenge.”

Grass took up many global causes, from international debt-relief to environmental pollution. He campaigned vigorously against the US-led war on Iraq in 2003, a cause that matched that of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s opposition. But he was not anti-American, and laughingly said the only reason why he had stopped travelling to the US was because of its ferocious bans on public smoking. Grass was never without his pipe.

He was one of the few German writers who could claim to be, if not a public intellectual, at least a public citizen. True to his democratic instincts, he and his German publishers used to conduct seminars for his translators every time a new Grass book appeared. The practice started in 1977 with The Flounder and became a tradition, beloved by translators. The seminars lasted from three days to a week, and Grass took part for most of the time. He hoped writers in Germany and abroad would follow suit.

Other writers always stressed Grass’s narrative skills. Hans Christoph Buch, a novelist and regular contributor to Germany’s liberal weekly Die Zeit, said: “He’s not a great thinker like Sartre. He’s not a brilliant essayist or intellectual like Hans Magnus Enzensberger. He’s a story-teller who writes from the gut.”

The South African novelist JM Coetzee summed up Grass’s work: “He was never a great prose stylist or a pioneer of fictional form. His strengths lie elsewhere, in the acuteness of his observation of German society at all levels, his sense of the deeper currents of the national psyche, and his ethical steadiness.”

That ethical steadiness took a severe knock with Grass’s late admission of his time with the Waffen-SS, trying to resist the Red Army’s advance on Berlin. His unit was not involved in the mass murders of Jews and Poles, but he admitted he had seen the Waffen-SS as “an elite unit” after being rejected when he volunteered for submarine duty at 15. He had previously written that he was involved in anti-aircraft defence before being taken prisoner by the Americans.

The admission sparked a storm of controversy. In sorrow, many of his supporters said the issue was not his membership of the Waffen-SS but his years of silence. In a long essay in Die Zeit, Jens Jessen wrote: “If Grass had spoken of his SS past earlier, he would not have damaged the fury of his moral interventions or his accusations that Germans had not gone far enough in coming to terms with their past. On the contrary he would have strengthened them and made them more credible because of his own Nazi-period mistake. What would it have been like if, while criticising Kohl and Reagan for visiting the cemetery at Bitburg, Grass had added: ‘I could have been one of the young Waffen-SS men buried there’?”

Defenders who dug into Grass’s record discovered that Grass had not concealed his brief SS service from his US interrogators in a PoW camp. His silence was literary. Grass himself put it down to a feeling of shame. “What I had accepted with the stupid pride of youth I wanted to conceal after the war out of a recurrent sense of shame. But the burden remained, and no one could alleviate it,” he wrote. He reminded readers that his mother had suppressed her rape by Russian soldiers for similar reasons. “It was not until after she died that I learned – and then only indirectly from my sister – that to protect her daughter she had offered herself to them. There were no words.”

Perhaps he decided to make the admission before he died, knowing that historians would one day stumble on his record and it would be better for his reputation not to have suppressed it for ever. Whatever the reasons, it is doubtful that the admission changed many minds. It only highlighted postwar Germany’s tortured character, and Grass’s position as its most tortured exponent.

The fact that Germany has become a “normal” country was in large part thanks to Grass. In a conversation with me early in 2003, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, Grass wondered whether Britain should not confront its own past more honestly. “I sometimes wonder how young people grow up in Britain and know little about the long history of crimes during the colonial period. In England it’s a completely taboo subject … Look at Iraq. This conflict goes back to colonial history. Don’t forget that.”

Grass’s anti-imperialism was directed frequently at the US, initially over Vietnam and later over Central America. He visited Nicaragua in 1982 when rebels who were armed and financed by the Reagan administration were trying to topple the Sandinista government. “How impoverished must a country be before it is not a threat to the US government?” he asked sarcastically. In 2012, he published a poem, What Must Be Said, which described Israel as a threat to world peace because of its threats to bomb Iran. The poem also said the German government might become complicit in war crimes for selling Israel a submarine that could carry nuclear warheads. The Israeli government declared him non grata. Grass responded by comparing the ban on his entering Israel to his treatment by the governments of Myanmar and East Germany.

Though the excitement provoked by his views on German history and German unification continued, his private life became more serene. In 1954, he had married Anna Schwarz, and they had three sons and a daughter. The marriage ended in divorce in 1978, and the following year he married Ute Grunert. This brought him two stepsons, and he also had a daughter from each of two other relationships. The voices of these eight children were featured in a second volume of memoirs, The Box: Tales from the Darkroom (2008). His third and final memoir, Grimms’ Words: A Declaration of Love (2010), took the fairytales of the Brothers Grimm as the starting point for an exploration of the political and social side of his life, noting, for instance, how the figure of Tom Thumb lay behind that of Matzerath.

In the mid-1980s he and Ute moved to the village of Behlendorf, to a remote farmhouse, about 15 miles south of the Baltic city of Lübeck, where he indulged in drawing and sculpture. It was not just a hobby; the sculptures were cast in bronze by a foundry in Munich and put on sale. He did engravings to be used as covers for some of his books. The couple spent part of the summer on a Danish island, and a few weeks in spring and autumn in their house in southern Portugal.

Ute and his children survive him.

•Günter Wilhelm Grass, novelist, born 16 October 1927; died 13 April 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment