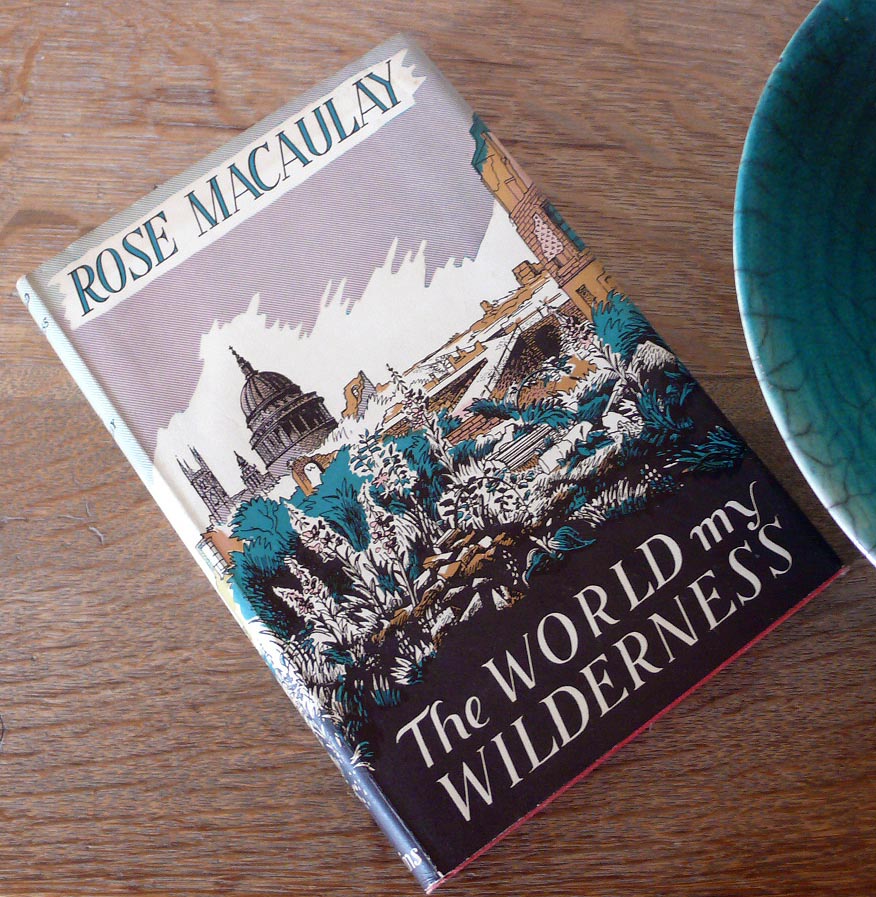

Re-Covered: The World My Wilderness

In her new monthly column Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print books that shouldn’t be.

Rose Macaulay (1881–1958) was one of the most prolific English writers of the first half of the twentieth century. She published twenty-three novels, twelve nonfiction volumes, and an abundance of journalism. I could make a case for the republication of any number of her novels, especially since the only one currently in print in the U.S. is The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Perhaps Potterism (1920), an entertaining, if now slightly dated, murder mystery that satirizes tabloid journalism—it was a best seller in both England and America. Or the intriguingly titled Told by an Idiot (1923), one of Macaulay’s most successful novels of ideas, in this case the examination—via three generations of one family—of sexual politics. Maybe Crew Train (1926), which tells the story of Denham Dobie, a young woman trying to adapt to life with her highbrow London relatives, and skewers the pretensions of the literary establishment. But of all Macaulay’s books, it’s one written much later that we most need to reread today: her penultimate novel, The World My Wilderness (1950), an elegiac, evocative depiction of the aftermath of World War II.

Although Macaulay was born in England, she and her siblings enjoyed a rather unorthodox childhood. In search of Mediterranean sun to ease their mother’s tubercular throat, the family spent seven years living in the small fishing village of Varazze in Italy, where, roaming the countryside and beaches, the children found what Macaulay’s biographer Sarah LeFanu describes as “a vision of paradise.” In 1894, they returned to England, settling in Oxford, where Macaulay quickly had to adapt to the more conventional life of a well-brought-up young Englishwoman. She attended Oxford High School and then Somerville (though she suffered a nervous collapse that meant she was unable to take her final examinations), after which she began writing. During World War I, she took on various roles in aid of the war effort: she was a nurse in a military hospital and a Land Girl in Cambridgeshire, followed by a stint at the Ministry of Information. It was while working there that the thirty-seven-year-old Macaulay met the man who was to be the love of the rest of her life, Gerald O’Donovan, a married writer and former Jesuit priest nine years her senior. Macaulay and O’Donovan fell in love and began a clandestine affair that was to last until his death in 1942. Macaulay never married or had children, nor did she have any other significant romantic relationships, even after Gerald died. Given that one of the legacies of the Great War was a generation of surplus women, her celibacy wouldn’t have necessarily been considered exceptional, though she was a little older than most of the partnerless women of the era. In the early twenties, she moved to London and quickly established herself on the city’s literary scene as a writer of sharp, satiric, and witty works that addressed the pertinent issues of the day. Widely liked and admired—she counted among her friends and acquaintances Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bowen, and Ivy Compton-Burnett—in the interwar years Macaulay was a well-known writer, broadcaster, and public intellectual.

Though it’s been out of print since the early eighties, The World My Wilderness was reissued by Virago Modern Classics last year. That it reappears in the UK amid the current vogue for new nature writing—a phenomenon spearheaded by the popularity of works by Robert Macfarlane, novelist Sarah Hall, and memoirist Helen Macdonald to name just a few—is perhaps no coincidence. At the heart of the novel are Macaulay’s gleaming descriptions of how the natural world has reclaimed the ruined postwar urban environment: “this scarred and haunted green and stone and brambled wilderness … a-hum with insects and astir with secret, darting, burrowing life.”

*

The novel opens in the Provence countryside in 1946, where the seventeen-year-old Barbary Deniston came of age running wild with the Maquis—that “uneasy fringe that hung around the Resistance, committed by their pasts to desperate deeds”—while her mother, Helen, a “large, handsome, dissipated, detached and idle” Englishwoman, turned the other cheek. Barbary is a child of war, a “jungle creature,” practiced in survival. It’s implied that she was tortured, perhaps even raped, by enemy soldiers, trauma that she doesn’t speak about but carries with her. There’s much of her mother in Barbary (and elements of Macaulay herself in both of them). Both push against the conventions of their sex. Helen was too indolent to ever behave as was expected. She fled polite society when she abandoned her first husband, Barbary’s father, back in England before the war. In France, she married again, to a fellow bon viveur named Maurice (whose son Raoul quickly became Barbary’s partner in crime). Maurice’s search for an easy life led him to engage in some genial collaboration with the Germans, for which he paid the highest price: the local Maquis, acting as judge, jury, and executioner, drowned him for his crimes. Despite this loss, Helen has no intention of returning to England, but she has made plans to send Barbary there instead, punishment, the girl infers, for her hand in her stepfather’s death. (Raoul, separately, is also sent to London to live with his uncle and aunt.) Helen hopes that Barbary’s father, Sir Gulliver Deniston—a celebrated KC who has also remarried—will be able to “civilise” their daughter where she herself has failed.

The Maquis inculcated a sense of lawlessness into Barbary and Raoul, and their elders are now unsure how to handle them. In the postwar French countryside, they “annoy the gendarmerie and the local authorities. Steal when they can; trespass on private property; sabotage motorcars; molest their fellow citizens.” Later, in London, they escape their homes and their guardians, hiding from the police in the blitzed ruins of Cheapside. This uninhabited no-man’s-land is “a wilderness of little streets, caves and cellars, the foundations of a wrecked merchant city, grown over by green and golden fennel and ragwort, coltsfoot, purple loosestrife, rosebay willow herb, bracken, bramble and tall nettles, among which rabbits burrowed and wild cats crept and hens laid eggs.”

It’s here among the “dripping greenery that grew high and rank, running over the ruins as the jungle runs over Maya temples, hiding them from prying eyes,” that Barbary finds what Macaulay, in a letter about her novel to her friend Hamilton Johnson, calls the girl’s “spiritual home.” These “broken alleys and caves of that wrecked waste” offer the traumatized, homesick Barbary a safe haven: “It had familiarity, as of a place long known; it had the clear, dark logic of a dream; it made a lunatic sense, as the unshattered streets and squares did not; it was the country that one’s soul recognised and knew.”

Barbary and Raoul swear their loyalty to fringe groups—first the Maquis in Provence, then the ragtag band of deserters, thieves, and black marketers they meet in London. They are united by their refusal to adhere to convention, law, and order. In the novel, tradition is juxtaposed with modernity. The annihilation of Barbary and Raoul’s childish innocence, and of society’s outdated Victorian sensibilities, is shown alongside the destruction of culture and civilization that the war has wrought. Sir Gulliver’s rather cursory attempts to tame his daughter have little effect on Barbary’s skittish savagery. Similarly, the armistice is described as having brought with it only the veneer of amity:

The peace that shrouded land and sea was a mask, lying thinly over terror, over hate, over cruel deeds done. Barbarism prowled and padded, lurking in the hot sunshine, in the warm scents of the maquis, in the deep shadows of the forest. Visigoths, Franks, Catalans, Spanish, French, Germans, Anglo-American armies, savageries without number, the Gestapo torturing captured French patriots, rounding up fleeing Jews, the Resistance murdering, derailing trains full of people, lurking in the shadows to kill, collaborators betraying Jews and escaped prisoners, working together with the victors, being in their turn killed and mauled, hunted down by mobs hot with rage; everywhere cruelty, everywhere vengeance, everywhere the barbarian on the march.

In the same way that the precise details of Barbary’s own wartime activities—both as a victim and as a perpetrator—are not dwelled on, the particulars of the myriad atrocities committed during the conflict are not Macaulay’s concern here. Instead, the novel asks the question of how we deal, both individually and collectively, with the aftermath of such barbarity.

*

Like many writers for whom the city was home, Macaulay remained in London throughout World War II despite the obvious dangers. Just as she’d done during the previous war, she volunteered. Though she was in her sixties, she spent her nights as an ambulance driver, hauling stretchers loaded with the injured in and out of the van and navigating the rubble-strewn streets while the city burned around her. She escaped physically unscathed, but she did lose her home and most of her possessions. On May 10, 1941, in what was at the time one of the worst nights of the Blitz, Macaulay’s Marylebone flat, as she described it after the fact, was “bombed and burnt out of existence.” This shattering material loss occurred during an already extended period of mourning. March of that year had been marked by two notable deaths: Virginia Woolf had committed suicide, a death that rocked the literary community—not a casualty of war in the strictest sense, though she did despair at the state of the world—while closer to home Macaulay’s beloved sister Margaret died from cancer. Then, the following month, Gerald O’Donovan’s youngest daughter, twenty-three-year-old Mary O’Donovan, perished from septicemia after swallowing an open safety pin. “Such a wretched way to lose someone,” Macaulay wrote, “much worse than enemy action, which would seem normal.”

“I am bookless, homeless, sans everything but my eyes to weep with,” she wrote to her friend Daniel George. The order in which she lists her losses is evidence of that which hurt the most. She had been collaborating with George on a book about animals, all the work for which was now gone. After the bombing, the loss of her library preoccupied her for many years. “My lost books leave a gaping wound in my heart and mind,” she wrote to her friend, the writer Storm Jameson. Eight years later, in 1949, after she had amassed many replacement volumes, the trauma remained raw. “I am still haunted and troubled by ghosts,” she confessed in the talk “Books Destroyed and Indispensable,” which she recorded for the BBC. “I can still smell those acrid drifts of smoldering ashes that were once live books.” In The Library Book, a fascinating account of the fire that destroyed four hundred thousand volumes in the Los Angeles Central Library in 1986, Susan Orlean explains that in Senegal “the polite expression for saying someone died is to say that his or her library has burned.” Macaulay, no doubt, would have well understood the meaning behind this phrase.

Hidden behind this act of very public mourning for her lost library was a more intimate, secret grief. O’Donovan died only a year after Macaulay’s flat was destroyed. Years’ worth of letters written to her from her lover were lost in the bombing, leaving her with very little to remember him by. It was this most harrowing of losses that provided the inspiration for her short story “Miss Anstruther’s Letters,” which Macaulay wrote while O’Donovan was dying. “What will I save?” Miss Anstruther asks herself, in her final desperate minutes in her flat in a bombed building just before the gas main blows. She piles books into a suitcase, only to remember, as she stumbles downstairs and is pulled to safety, that she’s left her recently deceased lover’s letters behind. Standing on the street, watching the building burn, she’s driven nearly mad with horror:

Everywhere buildings burning, museums, churches, hospitals, great shops, houses, blocks of flats, north, south, east, west and centre. Such a raid there never was. Miss Anstruther heeded none of it: with hell blazing and crashing around her, all she thought was, I must get my letters. Oh, dear God, my letters.

These losses—of Macaulay’s home, her library, her work in progress, her letters, Woolf, Mary, Margaret, and, most painful of all, the man she had been in love with for nearly a quarter of a century—all underpin The World My Wilderness. After Maurice is executed, Helen’s longing, “hungered in her night and day, engulfing her senses and her reason in an aching void.” Like Macaulay, Helen is unable to grieve her loss publicly, but it eats away at her on the inside: “She tried to fill the void, stupefy the ache … but still it deepened about her, as if she was in a cave alone.” Her daughter, meanwhile, poleaxed by her own grief and loss, seeks refuge in the “caves” of the ruins of the historic heart of London. The novel merges intimate, personal losses with the destruction of civilization itself.

From the burning of the Library of Alexandria to the fall of Rome, the destruction of both books and cities has always been analogous to the destruction of a civilization. “Burning books is an inefficient way to conduct a war, since books and libraries have no military value, but it is a devastating act,” writes Orlean in The Library Book. “Destroying a library is a kind of terrorism.” In her writing, Macaulay became increasingly fascinated with relics and wrecks, from her 1941 essay “The Consolations of the War” through The World My Wilderness and on into her nonfiction study Pleasures of Ruins (1953). The writer Penelope Fitzgerald remembers Macaulay, then in her seventies, “scrambling” through the rubble in the years after the war: “She shinned undaunted down a crater, or leaned, waving, through the smashed glass of some perilous window.” As Lara Feigel puts it in The Love-Charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War, “Macaulay, consumed by secret, silent grief for Gerald O’Donovan, sought out landscapes that reflected her internal state of mind.” Like Barbary, Macaulay found her spiritual home amid the wreckage:

Here, its cliffs and chasms and caves seemed to say, is your home; here you belong; you cannot get away, you do not wish to get away, for this is the maquis that lies about the margins of the wrecked world, and here your feet are set; here you find the irremediable barbarism that comes up from the depth of the earth, and that you have known elsewhere. “Where are the roots that clutch, what branches grow, out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, you cannot say, or guess …” But you can say, you can guess, that it is you yourself, your own roots, that clutch the stony rubbish, the branches of your own being that grow from it and from nowhere else.

At the start of the Blitz, between September and November 1940, nearly thirty thousand bombs were dropped on London. It was unclear whether the city would survive the assault, or whether its inhabitants were witnessing the annihilation of their city as the inhabitants of Jerusalem, Babylon, and Pompeii had before them. Eyewitnesses on the night of the raid that reduced the City to the ruins Macaulay writes about described the incendiaries as falling from the sky as thick as “heavy rain.” From Aldersgate to Cannon Street, Cheapside and Moorgate were ablaze. Nineteen churches were destroyed, and thirty-one of the thirty-four guildhalls. Paternoster Row, the street that was the center of the London publishing trade, was completely engulfed in flames, resulting in the destruction of five million books. “The Great Fire had come again,” writes Peter Ackroyd in his biography of London.

The World My Wilderness is a book born of loss and destruction. It deals in the grim realities of a civilization that’s brought itself to the brink. And yet it is not without optimism. Although Barbary’s father’s attempts to civilize her can’t be considered a success, she stops living in the ruins. To describe her as tamed would be a step too far, but she does find something resembling peace, as does her mother. Macaulay ends her story, however, not with Barbary or with Helen but with Richie, Helen’s eldest child and Barbary’s twenty-three-year-old brother. At the end of the book, Richie, whose studies were put off while he was away fighting for his country, is an undergraduate at Cambridge. On the last evening of his summer vacation, Richie walks from Moorgate station to his father’s house on the Embankment, through the ruins:

Shuddering a little, he took the track across the wilderness towards St. Paul’s. Behind him, the questionable chaos of broken courts and lanes lay sprawled under the October mist, and the shells of churches gaped like lost myths, and the jungle pressed in on them, seeking to cover them up.

Like the flowers and weeds that grow among the rubble, Macaulay’s novel ends with the hope of redemption, and the possibility of continued life. There are plenty of novels about wartime London, but few that concern themselves with the immediate postwar period. None that I’ve encountered evokes it with as much sensitivity and beauty as Macaulay’s.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review and Literary Hub, among other publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment