|

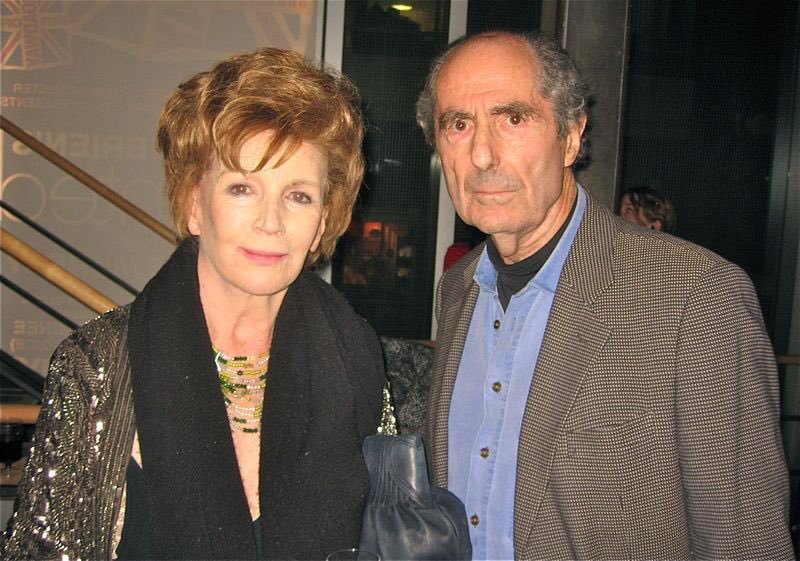

| Edna O’Bruen and Philip Roth |

The Great Comic Literary Conquistador: Edna O’Brien pays tribute to her friend and fellow writer Philip Roth.

In her poem, ‘One need not be a chamber to be haunted’, Emily Dickinson wrote of the mind’s many niches and the spectral encounters of night. I have been thinking of the forbidding rooms of Philip Roth, a man so studiously private in life, and as an author zanily, volubly confessional. He set forth his own manifesto in a few terse words: ‘Fiction is not a beauty contest and fiction is not autobiography.’ Were he to write an autobiography, he maintained, it would make Beckett’s The Unnamable read like one of the rich narratives of Charles Dickens.

‘I read fiction,’ he wrote, ‘to be free of my own suffocatingly, boring and narrow perspective on life, and to be lured into imaginative sympathy with a fully developed narrative and point of view. It is for the very same reason I write it.’ His inclination was towards the loopy, the carnivalesque, the aggressive, the clown-like, and filled with the titanic indiscretions that he so admired in Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King.

So, the Parental Room. A family of four: father, mother and two sons, one the putative writer, both rebellious and bedevilled by longstanding loyalties. ‘A Jewish man,’ he would go on to say, ‘with his parents alive is half of the time a helpless infant. Listen. Come to my aid. Spring me from the role of the smothered son.’ The other half of him did spring to become the great comic literary conquistador.

He loved his parents, his father who was dogmatic, unswerving, but with limitless pride in his son. A father who showed great stoicism after a financial setback in his mid-forties, and to Philip seemed an amalgam of Captain Ahab and Willy Loman. He feared more than anything that he would disappoint both his parents, that he would in fact break their hearts.

His relationship with his mother is more intricate. She remained the secret siren, perpetually curled up inside him. She was self-effacing, yet had her own particular witchcraft, so that she could pass through windows or concoct stratagems from her apron pocket. Up to the age of five – before he went to school – they were alone, blissfully alone; he, the little kitchen jester, doing impersonations of Jack Benny and other popular television characters, and she, though in ripples of laughter, convinced that she had given birth to another Albert Einstein. So umbilical, abiding and intermeshed was this relationship with mother, that when Philip had a coronary bypass in middle age, he invites us to witness his beautiful reverie, as he gives suck to the newborn infant inside him. He is engaged in blissful ruminations, in which he does not have to use his imagination at all, merely partaking of the most delirious maternal joy.

By contrast, the Conjugal Room is lawless, scatological and filled with sexual extravaganza: ‘When he is sick, every man wants his mother; if she is not around, other mothers must do. Zuckerman [one of his fictional creations] was making do with four other women.’ They constitute the weepers, the love terrorists, the fault-finders, the avengers and the hotsie-totsies. They are all fluent and fiery. This room is both cradle and battlefield. They represent ecstasy and nemesis. There is Faunia in The Human Stain, alas a loser; the rapacious Monkey in Portnoy’s Complaint, to whom the protagonist, Portnoy, recites Yeats’s ‘Leda and the Swan’ at a torrid sexual juncture; and the majestically unhinged Maureen in My Life as a Man, for whom Roth seems to have a remaindered sneaking fondness.

‘Whew. Have I got grievances,’ Portnoy says to his psychiatrist, in his raging, incessant spiel. Of the four hundred and thirty thousand citizens who bought the hardback, there were also a great tally of grievances. It was a repellent book, a burst of rage and romp, filled with fetid indiscretions and blasphemies, but most heinous of all was his vile depiction of women, both Jew and gentile. The author protested. He was not a screwball in search of catharsis, he was not a hating or avenging son, and his only crime was to have observed the human granules all around him and hone it into fiction. The impetus for the book came to him when he realised that Portnoy’s guilt was a source of rich comedy. Moreover, he said to those disbelieving philistines, poor Alexander Portnoy was merely crying out for redemption.

Roth became famous overnight, accruing all the trappings and gossip and misconception that fame brings. He left New York and went to the Yaddo Gardens retreat for several months. From time to time he would send salvos back. It was not his intention to slither out of the slime, but rather to slide back into it. He was not interested in American pieties, propaganda, moral allegory, appeasement or the conceits of the avant-garde about style, structure, symbolism and so on.

He had said he was influenced by the mood of the sixties; the sexual liberation and pervasive theatricality emboldened him to write as he did, while at the same time, privately, he was expanding his concerns and his themes. He became more politicised, railed against Nixon’s malevolent administration and, as he saw it, a president on the verge of mental disorder. As a citizen of America, the Vietnam War both appalled and mortified him. He went into seclusion and employed himself for many years, up in Connecticut, turning the sentences around and around, day by day, allowing himself a newspaper on Sundays, but with one proviso, that the ‘Arts’ page be removed before the paper was delivered. He had cut himself off.

It is a moral and intellectual leap from Portnoy’s Complaint to American Pastoral, and a more astonishing one to Sabbath’s Theater. Naturally, there is the same merrymaking music of the transgressors, and Micky Sabbath, the pagan puppeteer, does indeed dabble in the brackish waters of licentiousness, but he is also death-haunted, marked by the tragedies that occur both in war and peace, and ultimately wounded by great love and real loss.

Flaubert spoke of his Royal Room, where very few were admitted. For every writer, there is a writer who has gone before, who is both colossus and shadow. For Philip, that person – and therefore that guest – would be Kafka. He admired the great punitive fictions of The Trial and The Metamorphosis, but his favourite story is The Burrow. A creature is building a vaulted chamber, a safe hole to hide in. His one tool is his forehead, just as a writer’s one tool is the mind. The creature is joyous when blood flows. It means he has worked unrelentingly, and the walls are beginning to harden. Philip chose the story as a testament of how art is made. He depicts a portrait of the artist in all his ingenuity, anxiety, isolation, dissatisfaction, restlessness, secretiveness, self-addiction and yet, the magical matter of a great story arising from all that human mess.

I visited Philip in many rooms over a period of thirty-six years. London, Connecticut, Essex House, where he and Claire lived for some time, and last of all, Seventy-Ninth Street. It was earlier this year. The change in him was almost imperceptible. The room had the same monastic neatness, books stacked everywhere, a larger pile on the table, close to where he sat, no flowers, no ornamentation, none of the empty liquor bottles such as John Berryman left in a hotel in Dublin, to where he had fled in an attempt to write. Propped on the hatch between the sitting room and the kitchen was a letter in a child’s hand. It said: ‘Dear Mr Roth, I would like to write a book with you.’

Philip was as curious and as mischievous as ever. We laughed. To my chagrin, he told me how wealthy he was and how soundly he slept – ‘Like an angel.’ Yet the fire was dwindling. I do not say this in retrospect, but I did feel the relevance of Prospero’s great line, which Philip had used as an epigram for Sabbath’s Theater: ‘Every third thought shall be my grave.’

It was raining and I could not stay long. Nor would he have wanted it. Time for his nap. He got out of his slippers and into his shoes.

‘Don’t come down with me . . . it’s raining,’ I said.

‘I’m coming down with you.’

We stood on the step in the porch, while the doorman braved the taxi-mad supplicants. He looked up and down the street and said, almost boyishly, ‘I take a walk every day, try to be friendly, hi Joe, hi Phil, hi Nathan,’ and then more urgently he gripped my arm and said, ‘You’re valiant, kid.’ It was not said in flattery, but rather as an incentive to keep going, to harden the walls of the burrow.

A taxi materialised, just in the nick of time. No more sentiment, no more laughs, no more anything.

Dear Mr Roth, I would like to write a book with you.

No comments:

Post a Comment