Re-Covered: The Mischief

In her monthly column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Let’s play “guess the novel”: It was written and first published in French in the mid-50’s, and is set over the course of a single summer. Its heroine is one of the jeunesse dorée, dissatisfied and bored despite her wealth and privilege. She drives a fast sports car, and idles away her days sunbathing on Mediterranean beaches and flirting with her boyfriend. She’s a capricious enfant terrible, and she’s stricken with jealousy at the happiness of a couple close to her, so she amuses herself by sabotaging their relationship, with unexpectedly tragic consequences.

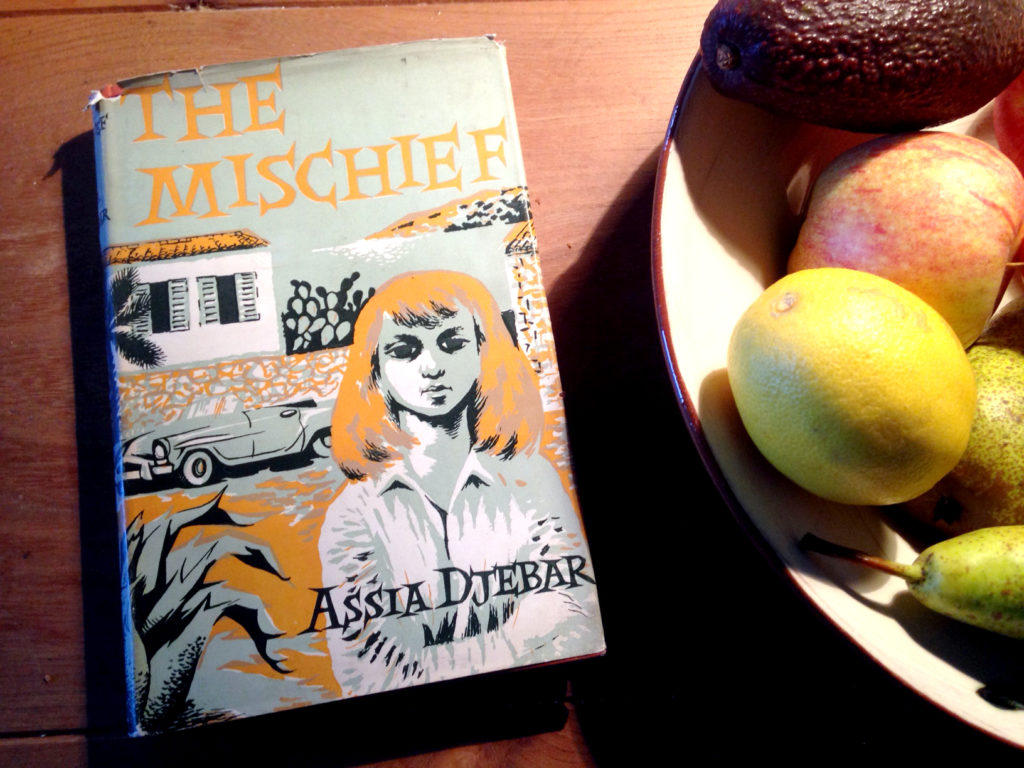

Surprisingly, I’m not talking about Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, but a lesser-known work by the Algerian writer Assia Djebar. La Soif was first published in France in 1957 (three years after Bonjour Tristesse) and nimbly translated into English by Frances Frenaye, as The Mischief, the following year. There are plenty of parallels between the two novels. Both were debuts written by precociously young women writers—Sagan was eighteen and Djebar twenty-one—a description that also applied to their heroines: Sagan’s seventeen-year-old Cécile and Djebar’s twenty-year-old Nadia. However, while Bonjour Tristesse remains famous, recognized today as a mid-twentieth-century literary sensation-turned-French-classic, The Mischief is barely remembered, out of print in both the original French and the English translation.

This isn’t to say that Djebar (who died in 2015 at the age of seventy-eight) is unknown. On the contrary, she’s remembered as one of Algeria’s most celebrated female writers and intellectuals. She wrote more than fifteen novels in French (which were then translated into more than twenty languages), and was a critically acclaimed film maker and internationally respected academic. She had the voice of an intersectional feminist long before the term became popular. “Her novels and poems boldly face the challenges and struggles she knew as a feminist living under patriarchy and an intellectual living under colonialism and its aftermath,” her American publisher Seven Stories Press wrote in a statement made upon her death. A decade earlier, Djebar had made headlines when she became the first North African woman (and only the fifth woman) to be elected to the Académie Française. In the years that followed she was regularly named as a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. She spent her entire life shattering glass ceilings: La Soif, for example, was the first novel written by an Algerian woman to be published outside of Algeria. Not that this impressive detail saved the book from being considered rather lightweight by contemporary critics. The comparisons to Bonjour Tristesse were not particularly helpful. Sagan’s novel, although notorious, had garnered mixed reviews, some of which were extremely damning; a “vulgar, sad little book,” wrote The Spectator. Although critics don’t appear to have been as harsh about Djebar’s novel, despite its “nicely plotted” and “skillfully executed” turns—as the reviewer in the New York Times described them—The Mischief was reduced to somewhat trivial juvenilia. This opinion only solidified as Djebar’s voice became more overtly political throughout the course of her career. Many of her later novels remain in print—from Les Enfants du Nouveau Monde (The Children of the New World, 1962), which documents the lives of women in a rural Algerian town who are drawn to the resistance movement through her impressive tetralogy about the history of Algiers that emphasizes the horrors of the country’s colonial past, its struggle for liberation, and the subordinate position of women in Maghreb society, which began with L’amour, La Fantasia (Fantasia, An Algerian Cavalcade, 1985) and ends with Vaste est la prison (So Vast the Prison, 1995). But with its ostensibly more frivolous storyline, The Mischief has fallen by the wayside.

*

Like Bonjour Tristesse, The Mischief is narrated in the first person, and like Sagan’s Cécile, who, when she recalls the summer she was seventeen, is beset by a “strange melancholy,” Djebar’s Nadia is haunted by a similar bygone episode in her life. “I had thought I could banish the past from my mind,” she says after she’s told her story, “but all the time it lay, like a mass of dense water, within me.” Nadia’s life is one of easy distractions—“the light rhythm of group excursions to the casinos and cinemas of Algiers, of rainy Sundays whiled away at surprise parties, of mad drives in sports cars as skittish as thoroughbred horses”—but these entertainments have left her cold. She’s “empty inside,” overly familiar with “the brackish fatigue of a morning-after, after wasting the night with jazz bands and cigarettes and facile gaiety, and facing with a heavy head and weary limbs the advent of a grey, grey dawn.” Only slightly older, Nadia looks back on the antics of her younger self. “My life was uneventful, superficial and empty,” she confesses, “of exactly the sort to justify a twenty-year-old’s cynicism and disappointment. So I was wont to reflect, with no other satisfaction besides that of my own lucidity.” Her candor adds to both her allure and her plausibility. Djebar’s ability to capture the ennui of excess contributes to the novel’s realism.

Then Nadia discovers that an old school friend, Jedla, and her husband, Ali, have rented the villa next to that of Nadia’s older sister Myriam (with whom Nadia herself is staying for the summer, at a popular, upmarket beach resort on the Algerian coast). Before long, Nadia begins playing games with their trust and affection. She sets out to seduce Ali as summer sport—“to satisfy my vanity and fill my idle time”—but a host of conflicting deeper currents are at work beneath the surface: “Amid the dull summer heat, a mysterious interplay of emotions was subtly and shiftingly weaving itself in the quiet air.”

Nadia’s mother died giving birth to her, thus she’s only ever known the affection of her doting father. He has older daughters by another wife, but Nadia remains his spoiled youngest child. This summer, however, he’s away in Europe, and Myriam is occupied by her own family—her husband, her child, and the new baby that’s on the way. Nadia is adrift, untethered from commitments, people, and responsibilities. She was, we learn, engaged to be married, but recently called it off. She has a sort-of boyfriend, Hussein—who makes up a foursome with her, Jedla, and Ali—but she toys with his affection, proving indifferent to his eager advances but desiring his attention. And then there’s the nature of her feelings toward Jedla. Nothing is made explicit, but something more than friendship is definitely implied. Glimpsing her for the first time since they were at school together four years earlier, Nadia, her “heart pounding,” realizes that the other woman’s “dark eyes had lived inside me all this time, buried in some turbid emotion.” So, too, all is not what it seems when it comes to the newlyweds’ relationship, something Nadia only comes to realize long after she has become embroiled in their lives, after which things quickly spiral out of her control.

As a haunting tale of roiling passions and power play, The Mischief is impressive, especially as the work of a writer only just out of her teens. But the text takes on an extra dimension due to the unique position that Nadia occupies. Her father is Algerian, but her mother was French. “With your mixed blood,” Hussein reminds her, “you’re on the borderline between two civilizations.” She has been raised in Algeria but “in Western style,” thus her “blonde hair and easy-going ways” mean she passes for European. As Hussein puts it, she’s “on the fence”: neither fully French, nor fully Algerian either. Djebar doesn’t dwell on this aspect of her protagonist’s identity, but the novel carries the undercurrent of racial and sexual politics, elements that haven’t always been given the attention they deserve.

*

Take the figure of Myriam, for example, whose life can be pieced together from scattered details: she married young, as was expected of her; to all outward appearances she’s a compliant and respectful wife, but her feelings toward her marriage aren’t straightforward—she “loved and feared” her husband, but also feels “a sort of embittered regret for the waste of her youth.” Myriam’s husband is never named, nor does he appear, yet he casts a shadow over the text. It’s no throwaway line, for example, when Nadia describes the way her Algerian brother-in-law “looked askance at my trousered legs and the tip of my cigarette burning in the darkness.” Then there’s the setting of the novel, the beach resort that’s “fashionable” enough to be “frequented by colonials.” Nadia’s family, Djebar takes pains to point out, are the only Muslims in residence (prior to the arrival of Jedla and Ali). Ali, it’s also worth noting, is a young Algerian nationalist with firm ideas of what his country needs: “People are always talking about colonials and colonialism, but the real trouble lies in our own lethargy, which leaves us open to exploitation. That’s what’s got to be shaken.” This tension, between Algeria and Europe, rears its head again near the end of the novel when Nadia tries to shock Jedla with “sordid […] scabrous” stories about her family:

There was no use talking about the tender voice of my father. Myriam’s submission to her husband, Leila’s satisfaction over having a European servant. Jedla wanted to think that money, emancipation and a European upbringing has spoiled and corrupted the whole lot of us, especially me. And probably she was right, at that.

Although Nadia defies many of the restrictions ordinarily applied to women in traditional Algerian culture, in reality she isn’t as uninhibited as she would like to be. Her own identity—as a woman, an Algerian, and a European—is complicated. On a variety of occasions she shows a vicious contempt for the Algerian women around her—her sisters Myriam and Leila, and Jedla—whom she thinks have been too quick to “submit to convention.” Yet at the same time, she’s not immune to the social conditioning that lies behind this subjugation, seeking refuge in the protection Hussein can offer her: “in this reassuringly masculine presence, everything nightmarish faded away.” Nadia is the focal point of a nexus of complicated assumptions, prejudices, and traditions, inadvertently representing different things to different people. This was something Djebar herself pushed back against her entire life. “I am not a symbol,” she consistently told people who tried to box her identity into certain categories. “Each of my books,” she told the French press when she was elected to the Académie Française in 2005, “is a step towards the understanding of the North African identity and an attempt to enter modernity.” She might have been young when she wrote it, but The Mischief was no exception.

*

Born Fatima-Zohra Imalayène, in 1936, in Cherchell, a small seaport village near Algiers, Assia Djebar was the pen name she adopted on the publication of her first novel, for fear the book might offend her father. Not, however, that he was a traditionalist. He was the only Algerian-born French teacher at the colonial school where he taught, and the unconventional driving force behind his daughter’s education. As Djebar explained, he “broke with Muslim conformity, which would otherwise almost certainly have kept me in seclusion as a marriageable maiden,” instead making sure his daughter stayed in school. As a consequence of which, in 1955, Djebar became the first Algerian woman to study at the École Normale Supérieure of Sèvres—one of France’s most elite educational establishments—though she was expelled only two years later for striking along with the Union of Algerian Students to protest France’s colonial rule. This was when Djebar wrote The Mischief, and although it wasn’t about the specifics of the moment, it was born from that tumult and very much its own political statement on a topic that Djebar would return to again and again throughout her life: the curtailing of womens’ freedom under outdated traditions passed off as the Prophet’s teachings.

Torn between two countries and two cultures, Djebar returned to Algeria after it won independence in 1962, but, feeling increasingly isolated—“there were only men in the streets of Algiers,” she told Le Monde—she returned to Paris. She spent time in America, teaching at universities in Louisiana and New York before returning again to France. Despite making it her home for much of her life, Djebar’s relationship with France was one of great ambivalence. French was the language she’d been educated in (despite speaking Arabic and Berber at home with her mother and grandmother, she didn’t learn to write Arabic until she was an adult). It was the language of her liberation, that which had enabled her to live a political, intellectual life that would have been out of reach to the majority of her female peers, those who’d been taken out of school at the age of ten. Yet it was also the language of her country’s oppressors and had been foisted on her—while Algeria was a French colony, teaching in Arabic was forbidden. “First it was the language of the enemy,” she explained, “then it became a kind of stepmother, in relation to the maternal tongue of Arabic.” By the end of her life, she was embraced by the French—speaking on Djebar’s death, President Francois Hollande called her “a woman of conviction, whose multiple and fertile identities fed her work, between Algeria and France, between Berber, Arab and French.” The Mischief takes us back to the moment when she was just beginning to explore these complexities, a young woman forging her own nuanced identity, as yet unsure that she would be heard.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment