Re-Covered: The Orlando Trilogy

In her monthly column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

The Orlando Trilogy—which has just been reissued in the UK by Bloomsbury (under the title Orlando King)—is British novelist Isabel Colegate’s masterwork about personal, political, and public mythmaking. Colegate takes the scaffolding for her tale from Sophocles’s Theban plays. Her Oedipus Rex is Orlando King, a young man who scales the greasy pole of power and privilege in the thirties. “We know the story of course, so nothing need be withheld,” she writes on the opening page. “We choose a situation in the drama to expose a theme: passing curiosity must look elsewhere, we are here profoundly to contemplate eternal truths. With ritual, like the Greeks. With dreams, like Freud. Let us pray.” The trilogy spans the middle of the twentieth century. By the end of the thirties, Orlando is a wealthy businessman and respected politician; he’s also inadvertently killed his biological father and married the dead man’s widow, and she has borne him his beloved daughter, Agatha. But the Second World War brings with it our hero’s downfall. Agatha, like Antigone before her, stumbles around in the wreckage—that of both the wider nation and her individual family—and finds herself forced to choose between her country and her kin.

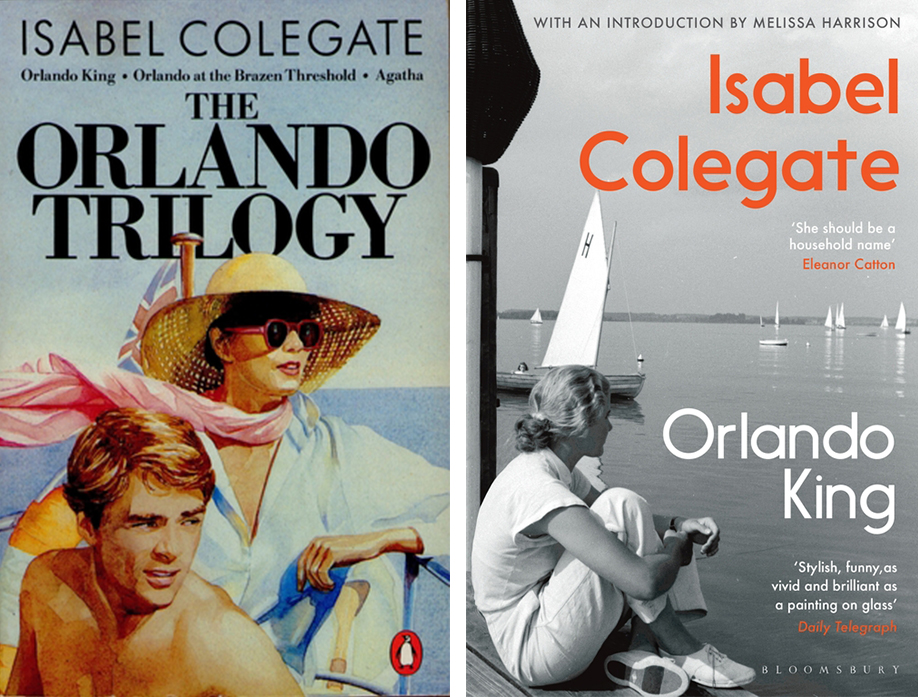

Originally published as three separate novels—Orlando King (1968), Orlando at the Brazen Threshold (1971), and Agatha (1973)—this is the third time that Colegate’s trilogy has been reprinted in a single volume. Penguin got there first in 1984, followed by Virago in 1996—so it’s certainly not a straightforward case of overdue reappraisal. As her latest publishers rightly point out, Colegate—who’s still alive today, age eighty-eight—has been ranked among the likes of English literary heavyweights Penelope Fitzgerald, Anita Brookner, Penelope Lively, and Elizabeth Taylor, yet until now, only two of her thirteen novels remained in print: her debut The Blackmailer (1958) and The Shooting Party (1980), which won the W. H. Smith Annual Literary Award and was swiftly adapted into an acclaimed film. Though other novels with which The Orlando Trilogy might be fruitfully compared—Lively’s Booker-winning Moon Tiger (1987), for example, or Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy (1960, 1962, and 1965)—have long been claimed as bona fide masterpieces (the former is a Penguin Modern Classic, and the latter an NYRB Classic), Colegate’s trilogy seems to find itself snared in a frustrating loop of rediscovery and neglect.

One can’t help but wonder if this has something to do with the boldness of the triptych. Could it be that there’s almost too much here for readers to grasp? If I were asked to describe the trilogy in only one line, I’d call it an impressive historical family saga that critiques the intertwined evils of hereditary privilege and capitalism. A mouthful of a sentence, to be sure. But these novels are also richly drawn, psychologically astute character studies. They’re novels that showcase distinct stylistic innovation in the form of Woolfian interior monologues and cinematic jump cuts. And we must not forget their mythic underpinnings, which, as Aileen Pippett observed in her 1969 New York Times review of Orlando King, never swamp the text but instead helpfully offer readers a route in to the narrative. With these clues in place, Pippett argues, “the story becomes more comprehensible and compelling.” Or, as Melissa Harrison puts it in her introduction to the new edition, the mythic “lends the domestic, the social and the political aspects of all three novels a kind of archetypal significance.” This is key. The Orlando Trilogy is very much a story about a particular period in British history, but in shining a light on the past, Colegate also illuminates the present.

When it comes to her depiction of the English upper classes, Colegate has no equal. Time and time again, her novels expose the corruption and hypocrisy that lies at the heart of the British establishment. As one of the characters in Statues in a Garden (1964), the novel she published immediately before Orlando King, angrily educates another: “They’re corrupt, inefficient, money-mad, immoral, unjust, based on falsehood. Their whole creed’s a pack of lies.” Despite any notion we might have of the twentieth century as an era of social progress, the upper classes have, for the most part, maintained their stranglehold on politics, commerce, and business. We need only look to British Parliament today to realize that, tragically, very little has changed. As Agatha’s stepbrother Paul writes in the final volume of the trilogy, “English and smug are synonymous words.”

*

From the Great Depression through Appeasement and the Second World War, and on into the postwar world, Agatha draws the trilogy to a close with both the Suez Crisis and the ongoing scandal of the Cambridge Five—the British spy ring who passed information to the Soviet Union—hanging over the country. Colegate’s concerns are the huge shifts—societal, political, and economic—that took place in Britain in the wake of World War II. “Caught up in the course of history,” her protagonists, whose interior landscapes she burrows deep into, are prisms through which we see these vicissitudes play out.

Orlando, the illegitimate son of two unmarried Cambridge students, is adopted by a man named King, one of the lovers’ kindly tutors. King takes the baby with him to France, where he settles in Brittany. When his adopted son comes of age, after an isolated but idyllic childhood, King sends him to England. The older man writes the younger one six letters of introduction—including one to Orlando’s biological father, Leonard, now a successful businessman and aspiring politician. Neither father nor son is aware of their blood ties; Orlando’s mother never told her lover that she was pregnant, and King hasn’t told Orlando the identity of his biological parents.

The England on which Orlando King opens—and the one to which twenty-one-year-old Orlando is first introduced—is a world of hunger marches and unemployment, but also of the excess and frivolity of the Bright Young Things. “What would you think he might have thought?” Colegate asks of her wide-eyed hero when he first arrives in London.

It was December. Nearly 1931. That’s a year we’ve heard of. Would he have seen dole queues, hunger marches? Would he have sensed the shabby political comings and goings, the presence, subdued, of the possibility of panic, the earth tremors beneath the civilization in decay?

None of this, however, makes its mark on Orlando. He’s preoccupied by the women, “and after that the luxury, the ease, the things to do and see and eat and say, the quickness, cleverness and beauty.” No doubt this has something to do with the seclusion and simplicity of his upbringing, but it’s also indicative of his key failing, the one that will eventually contribute to his undoing: his lack of heart.

Still, at first Orlando’s future looks bright. King’s introduction is all that’s needed to admit him entry into the old boys’ network. Orlando is charming and good-looking: he attracts women and impresses men. Swapping his baggy corduroys and fisherman’s jerseys for spats and a cigarette holder, Orlando isn’t so much indoctrinated by these men as smoothly assimilated into their world. And once there, he immediately makes himself at home: “admiration he took for granted wherever he went.” As his friend Graham keenly observes, Orlando is clever and articulate, but perhaps most important of all, he’s young: “Youth sits on Orlando like the dawn on the mountains, religiously immanent, lending him the illusion—if it is an illusion—of warmth.” Certainly it’s an illusion. Artifice, in all its guises, stalks Orlando’s rise to power and success, especially when it comes to his entry into politics. Copying the men around him, from whom he takes his lead, he treats politics like a game. It’s Lord Field (Conrad), Leonard’s landowning brother-in-law and Orlando’s mentor, who first floats the idea to the younger man. “I’m not holding out to you any idea of your duty,” he tells his protégé, “or of glory or renown or anything like that. I’m just holding out to you the sheer fun of the thing.”

There are some who are battling for a fairer world. Graham, who’s a communist, is a case in point, but he’s a rare exception to the money-grabbing Tories who make up the vast majority of Orlando’s associates. These are men content to double down on England’s still class-riven status quo and protect their own interests, and to hell with any notion of the greater good. This, of course, is one of the factors that leads to the popularity of Appeasement, of which Orlando—who, by this point in his ascendance, is a Conservative MP as well as the chairman of a company that produces armaments—is a key proponent. He’s “not above making a packet out of the manufacture of bombs,” as one of his stepsons observes to the other.

Orlando gives a speech to Parliament in which he claims that the Nazi Party’s exploits, although troubling, are “nothing to do with politics.” It is, as Harrison shrewdly asserts, “a breathtaking piece of ideological equivocation to rival anything we have recently witnessed at the dispatch box.” This is part of a larger argument that runs through Harrison’s essay: the strange uncertainty of our current time makes these books more pertinent today than ever before, regardless of their historical specificity. To read The Orlando Trilogy now, Harrison suggests, “during another period of seismic change, lends it particular resonance, for the questions Colegate’s characters struggle with echo clearly today: how should we balance individualism with the good of the collective? Is real change desirable, or even possible any more? What of duty and patriotism and religious faith—do they have any currency? Has capitalism disrupted our moral instincts? Where, if anywhere, might hope lie?”

As Colegate so brilliantly illustrates, class, politics, and power are inextricably entwined—as they still are in Britain, and so many other Western countries, today. The men in charge like to talk about duty and responsibility, of the loyalty one owes one’s country and how important it is to play by the rules; but they’re also the ones who’ve set—and can shift—the parameters of the game. “You’re always climbing up the ladder, that’s your world,” Agatha says when she angrily confronts Conrad in the final book, “that’s your world, the ladder with the rungs in it and everything according to the structure of rules which you’ve made, respect for the man who climbs the ladder fastest.” It’s Graham who, very early on, sums the situation up most plainly and pithily: “Mr Orlando is a perfect gent. In other words a perfect shit.” Conrad, for example, has no trouble squaring the regular visits he pays to a certain Mayfair establishment with the notion he has of himself as a gentleman of honor and scruples. We know he’s a hypocrite. But when, toward the end of Agatha, he unhesitatingly betrays one of his closest family members, there’s still something shocking in the full revelation of just how cruelly misshapen the so-called morals he claims to hold really are.

*

This is what Colegate does with excellence: she never resorts to the cheap and easy option of poking fun at her subjects, the route so often taken when it comes to the depiction of the English upper classes. Instead, she takes them just as seriously as anyone else, but in doing so, she strips them bare, exposed for all to see. As the screenwriter Julian Fellowes puts it so perspicuously in his introduction to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of The Shooting Party—which is set on a country estate on 1913—“By 1914, Colegate is saying, ‘being a gentleman’ had more to do with choosing the correct shirt studs than honour, more to do with shooting well than truth.” Fellowes cites The Shooting Party—both the novel and the 1985 film adaptation—as an important inspiration for both the film Gosford Park and the hugely popular TV series Downton Abbey. Though Colegate herself has been sidelined, there’s no question that she’s played an integral part in the popular culture’s notion of early twentieth century upper-class British life.

Colegate’s novels offer readers clear-eyed, illuminating windows onto this now bygone world. As an interview with her that ran in Country Life magazine in 1998 pointed out, Colegate’s insight into this particular “strand of English society associated with the landed gentry will be of interest to future social historians—in the way that Trollope, say, is today, as evidence of the society he knew.” And indeed, it’s a world she knows—or once knew—firsthand. Her father, Sir Arthur Colegate, was a Conservative MP, and both he and his wife came from families with country seats. On the other hand, however, one could just as vehemently argue that her novels aren’t so much depictions of a long-dead world. They are portraits of an all-too-recent past, the tenacious vestiges of which are still hugely influential in contemporary Britain. This, after all, is exactly how Colegate herself thought of the trilogy when she was writing it in the late sixties and early seventies, an era more commonly associated with free love, feminism, and social change. She was under no illusions that she was writing historical novels. She was merely unpacking the early years, the echoes of which she still saw playing out around her.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, The Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment