Invented memories: From psychiatric disorder to tricks for writing novels

There is a type of amnesia that prevents the formation of new memories, its place taken by confabulations. The writer W. G. Sebald used this illness to relate the story of a family member who ended his days in a psychiatric hospital

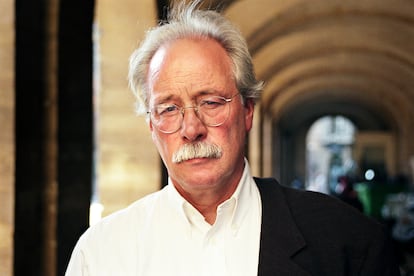

W. G. Sebald was a German writer who died at the beginning of the century in Norfolk (United Kingdom), in a traffic accident at the age of 57, after suffering a heart attack. He stood out for altering reality without being noticed, that is to say, for constructing fictions and with them achieving what is called the “reality effect.” Sebald used photographs to illustrate his texts. In one of his books, entitled The Emigrants, the writer used his own memories to reconstruct four biographies, four lives of people who one day had to emigrate and leave their roots in search of other branches.

One of the chapters is dedicated to a great-uncle of the writer, a peculiar man who spent his life working in luxury hotels and ended up as a butler and man of company to the son of a wealthy banker. At one point in the narrative, Sebald tells us that his great-uncle told stories so far-fetched that he seemed to suffer from Korsakoff’s syndrome. And it is here that the narrative begins to take on a scientific orientation, since Korsakoff’s syndrome is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder related to a severe deficiency of vitamin B1 or thiamine, which in most cases is associated with alcohol consumption.

The main symptom of this syndrome is a marked loss of memory; amnesia in its two basic types, i.e., anterograde amnesia, or the inability to form new memories, and retrograde amnesia — the inability to remember events that occurred before the onset of the disorder, although childhood memories are usually preserved. To this must be added the confabulations, especially in the first stage of the disease. Hence, fiction suddenly jumps into the patient’s daily life. This is a symptom that connects directly with the unconscious; the workshop — let’s call it that — of the narrators.

In The Emigrants, the author retraces the last days of his great-uncle’s life. At this point, we no longer know if he really existed or if it is another of his healthy confabulations, as when he tells us about his admission to the psychiatric hospital and the electroshock treatment his great-uncle attended punctually and stoically.

Dr. Abramsky, in charge of applying the therapy, described to Sebald that his patient received the shocks without complaining, with the electrodes on his forehead, a rubber wedge between his teeth, and tied to the table with straps “like a corpse that is about to be thrown into the sea.” The reality of all this is that electroshock is a method in which a majority of patients present memory disorders after its application, which leads us to think that Sebald’s literature is constructed with the material with which memory is invented when the memory itself has no choice but to falsify the facts.

In his literary game, Sebald leads us through a gallery of mirrors where autobiography is mixed with travel and scientific knowledge. The descriptions of nature are so meticulous, delve so deeply into detail, that they become a poetics of the quantum world. They suggest to us that beneath the layers of our reality lies a whole universe of latent phenomena.

No comments:

Post a Comment