John Lennon at 80: Zen, Haiku, and His Ties to Japan

The first Beatles record Hirota Kanji bought was the single “Help!” in 1965. He had seen the Beatles first film, A Hard Day’s Night, the previous year, and been charmed by the freshness of the band’s music. “I was a junior high school student at the time, and mostly listened to standard Japanese pop music [kayōkyoku], so I was amazed by this new rhythm. They had a poppy sensibility too, as well as appealing personalities you felt you could identify with.”

Hirota’s favorite Beatle was George Harrison. But when John Lennon was shot dead by a crazed “fan” on December 8, 1980, he says the shock brought home to him what had made Lennon so special.

“When John was killed, I was in graduate school writing my master’s thesis. I remember turning on the TV early in the afternoon. A caption ran across the bottom of the screen, saying John Lennon had been shot. Then, not long after, I learned on the news that he was dead. It was such a shock. There was no way I could concentrate on writing my thesis, that was for sure. I ended up taking on the job of editing a special memorial publication put out by a fan club I helped to run. We decided to introduce his life through the work. Since he sung about himself so often, by arranging the songs in the right order you could basically tell the story of his life.”

Retracing the course of the life in this way, Hirota was struck by how Lennon had been drawn to Japanese culture after his meeting with Ono Yōko, and was surprised by how profoundly he had been influenced by the world of Zen and haiku.

The Double Fantasy: John & Yoko exhibition attracted 700,000 visitors when it was held in Liverpool. It is currently being held in Tokyo, where a Japan Exclusive corner displays items showing the links between Lennon and Japan.

A Fateful Meeting at a London Gallery

John had been curious about Japan before he ever met Yoko. Hoshika Rumiko, the former editor of Music Life magazine who succeeded in getting an exclusive interview with the Beatles in England in 1965, remembered Lennon asking her about “sumō wrestlers and ukiyo-e.” A friend at art school had owned a book of old photos of Japan, he said, including some “beautiful” photos of sumō wrestlers. He spoke of his ambition to visit Japan one day and see its unique culture for himself.

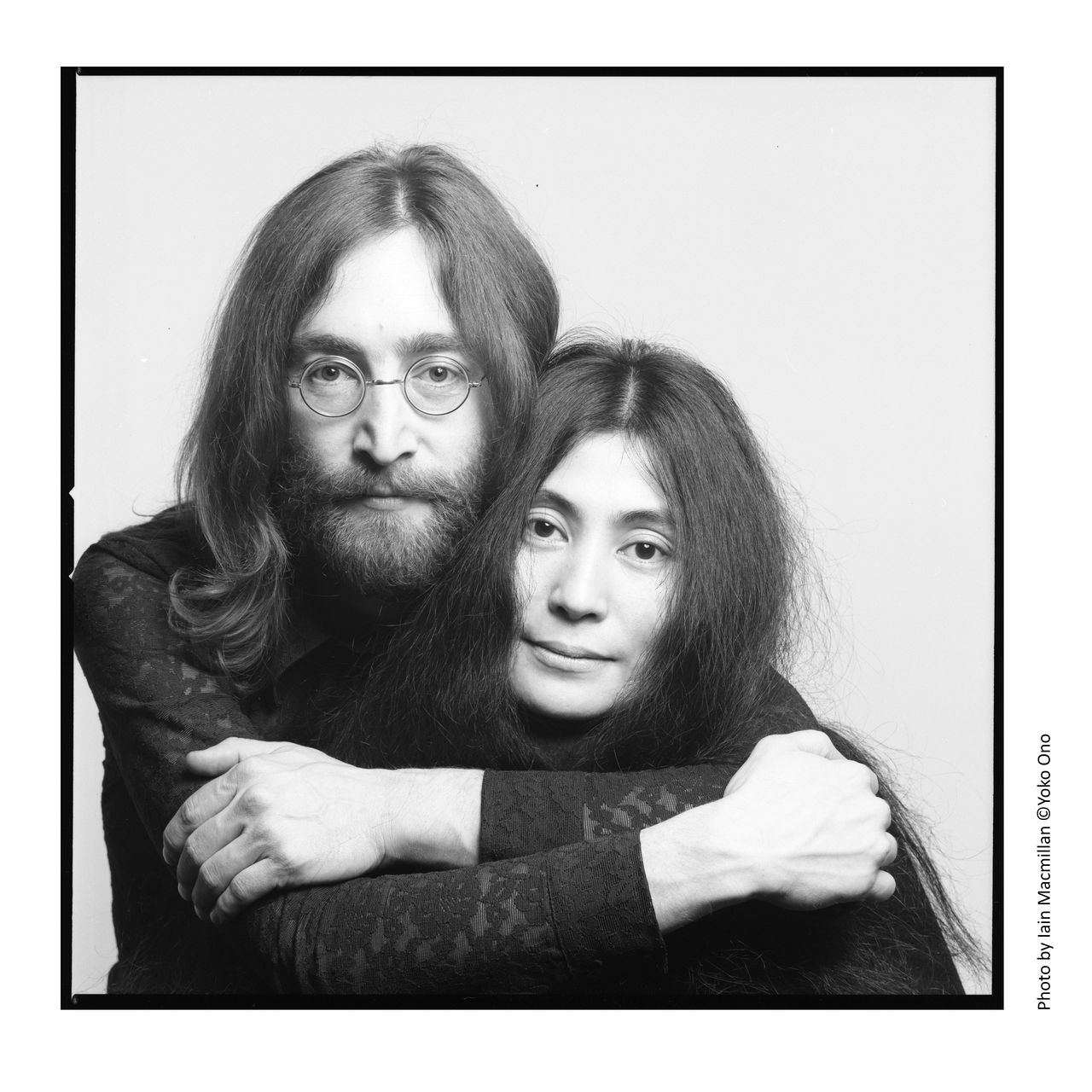

The next year, when the Beatles came to Japan for the first time, Lennon broke through the strict security designed to keep the band penned safely in their hotel and bought several Japanese antiques as souvenirs. In November that year, he visited a private showing of a solo exhibition by a Japanese artist named Ono Yōko in advance of its official opening at the Indica Gallery in London. Initially skeptical about conceptual art, to his surprise Lennon found something in Ono’s work that resonated with him as a fellow artist. He recognized a kindred spirit. The decisive moment came with a piece called “Ceiling Painting.” Visitors to the exhibition climbed a ladder to where a small piece of white canvas and a magnifying glass hung suspended from the ceiling, then peered through the magnifying glass to discover tiny writing spelling out the single word “YES.” Lennon always spoke of how he had been impressed by the positivity of this message. The “Ceiling Painting” that brought John and Yōko together is one of several Ono works recreated at the Tokyo exhibition, along with “Apple” and “Painting to Hammer a Nail.”

The couple’s relationship therefore began through art. “From around 1968, the musical differences between the members of the Beatles became increasingly clear,” Hirota recalls, “and tensions within the band became more frequent. John was quite clear that making music with Yōko would be more fun than being stuck in the band, and once they got married in March 1969, he decided to split from the Beatles and pursue a new direction with Yōko.”

A Pared-Down, Haiku-Like Sensibility Comes to the Fore

During the years of the hippie movement, which reached its zenith during the 1960s, many people in the West became interested in Eastern philosophy. Within the Beatles, George Harrison’s lifelong interest in Hinduism was well known; John too was influenced by Indian philosophy, Buddhism, and other aspects of Eastern thought. In particular, he was strongly drawn to the Zen view of the world and the haiku sensibility.

“During the sixties, a lot of spiritually inclined young people in Western countries learned about Zen through the English books of D.T. Suzuki. It would certainly be no surprise if Lennon was reading them too. And although we can’t know how directly responsible Yōko’s influence was, it’s a fact that he became increasingly interested in haiku after they got together. There was a shift away from the ornate, psychedelic sound of some of his earlier music to a more stripped-down approach, marked by simple and allusively poetic lyrics, in songs like ‘Across the Universe’ and ‘Because.’”

In an interview to mark the Japanese release of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band in 1971 (the album had been already been released in the UK in 1970), Lennon admitted that Zen and haiku had been a major influence on his recent writing. “I think haiku is the most beautiful poetry I’ve ever read. I’d like to simplify my lyrics [and make them] as beautiful as haiku. In the album, I’ve made the lyrics very simple and the music is very simple, and I feel as though it has a Zen spirit to it.” He double-checked the vocabulary before adding, “This album is shibui,” borrowing a term used in Japanese aesthetics to describe a simple, rough-hewn, unobtrusive kind of beauty.

Inspired by Bashō and Kabuki

In January 1971, John and Yōko visited Japan again in a private capacity. The couple visited her family home in Tsujidō (part of Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture) as well as Sagano and Mount Hiei in Kyoto. Lennon apparently spent much of their time in Kyoto absorbed in R.H. Blyth’s classic books on haiku.

In Tokyo, they visited the Hagurodō antiques shop in Yushima. The shop’s owner, Kimura Tōsuke (1901–92), remembered the couple turning up unannounced and saying that they wanted to look at ukiyo-e prints. Initially, Kimura was not sure who his famous visitors were. He later remembered his meeting with Lennon in the following terms.

Kimura invited the couple to his house, where he kept some of his finest pieces, to allow them to peruse his collection at their leisure. The visit promoted something of a buying frenzy in Lennon, who snapped up numerous examples of haiku poetry by Matsuo Bashō, Kobayashi Issa, and Ryōkan, as well as Zen paintings by famous artists like Hakuin and Sengai. At first, Kimura did not know whether he was dealing with a connoisseur with an unusually discerning eye or a crazy rich man. Lennon was particularly touched by a tanzaku (vertical poem strip) inscribed with Bashō’s famous haiku: “Old pond,/ frog jumps in,/ sound of water.” Lennon clutched the poem close as if determined not to let it go, and pleaded: “When I get back to London I’ll build a Japanese-style building or tea house and display the poem in an alcove and enjoy looking at it every morning and night, just like a Japanese person would. So please don’t be upset or feel that I am depriving you of this piece by buying it and taking it home with me.”

Kimura remembered how happy he had been to hear these words. “In Japan, there is a tendency with art to regard items favored by the nobility as superior, or value art that flatters the rich and powerful. But he was not interested in things like that at all. The art I deal in is the art of the ordinary people—and the person who responded to it most keenly was a former Beatle.” In more than 50 years in the business, Kimura said that Lennon was his first customer who understood what made his best pieces special without needing any explanation.

Kimura, an individualist with an antiauthoritarian streak, took a shine to John. When his visitors said they had an hour and a half to spare, he offered to take them to the Kabukiza for a glimpse of Japan’s famous theatrical traditions. Kimura hoped to show them one of the spectacular, flamboyant performances for which kabuki is famous. But the play was Sumidagawa, with no spoken dialogue, only mime-like dance performed to a shamisen accompaniment. It is a somber tale about a bereaved mother searching madly for her abducted child, only to find his grave far from home on the banks of the river of the play’s title. Kimura was sure the performance would be inaccessible for a first-time visitor, but was soon surprised to notice tears streaming down John’s cheeks, with Yōko gently wiping them away. There was no way John could understand the story or the details of the performance, Kimura thought. But after watching a small part of the next piece on the program, a more typically extravagant performance by the popular actor Ebizō, then a young man, Lennon quickly decided he had seen enough. What he could see in his mind’s eye was more important to him than the action unfolding on stage, Kimura concluded.

Zen Art and “Above Us Only Sky”

Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769) and Sengai Gibon (1750–1837) were Rinzai Zen monks who taught that anyone can achieve enlightenment. They preached this message among humble, ordinary people in eighteenth-century Japan, and left behind large numbers of distinctive Zen paintings and calligraphy. John bought works by both artists. “It seemed like he was quite knowledgeable about Hakuin and Sengai, and their ideas resonated with him,” Hirota says. “His understanding of haiku also evolved rapidly from 1969 on. He particularly liked haiku that reflected the spirit of Zen—moving poems that viewed the self as a small part of the wider universe, and aimed at a kind of loving union with nature.”

“The song ‘Imagine,’ released in 1971, seems to evoke renga, the linked verse form that gave birth to haiku,” Hirota adds. “In recent years, some Zen monks have pointed out that the song’s vision of the world is rooted in Hakuin’s teaching that ‘hell and paradise are nothing but reflections of the human mind.’”

Like Hakuin, Sengai traveled around the country bringing his teachings to the people. He disliked authority and was known for being a free spirit. After becoming abbot at the Shōfukuji temple in Hakata Fukuoka, he worked to restore the ruined temple buildings, while also drawing humorous Zen paintings that were popular with ordinary people. He sought harmony and points of common ground between religions, unconcerned with doctrinal differences between Shintō, Buddhism, and Confucianism, or between different Buddhist sects.

“John freely admitted that ‘Imagine’ was inspired by Yōko’s book of poems, Grapefruit, with its ‘instructions’ to the reader to ‘listen’ and ‘imagine.’ The influence of Western utopian thinking is also readily apparent. But I think the song was also born from a combination of the ideas of Hakuin and Sengai, who brought their message to ordinary people in accessible, easy-to-understand language and taught them to live freely, without fear in their hearts.”

The Househusband Years and Time in Japan

After their marriage, John and Yōko worked to bring their message of peace to people through a variety of happenings in cities around the world. Following the release of the Imagine album in late 1971, they moved to New York, where they mixed in radical left-wing circles and were active in the movement against the war in Vietnam. The Nixon administration, alarmed by John’s influence, ordered him deported from the country. The couple promptly launched an appeal and resolved to stay put in the United States until Lennon’s visa was reinstated.

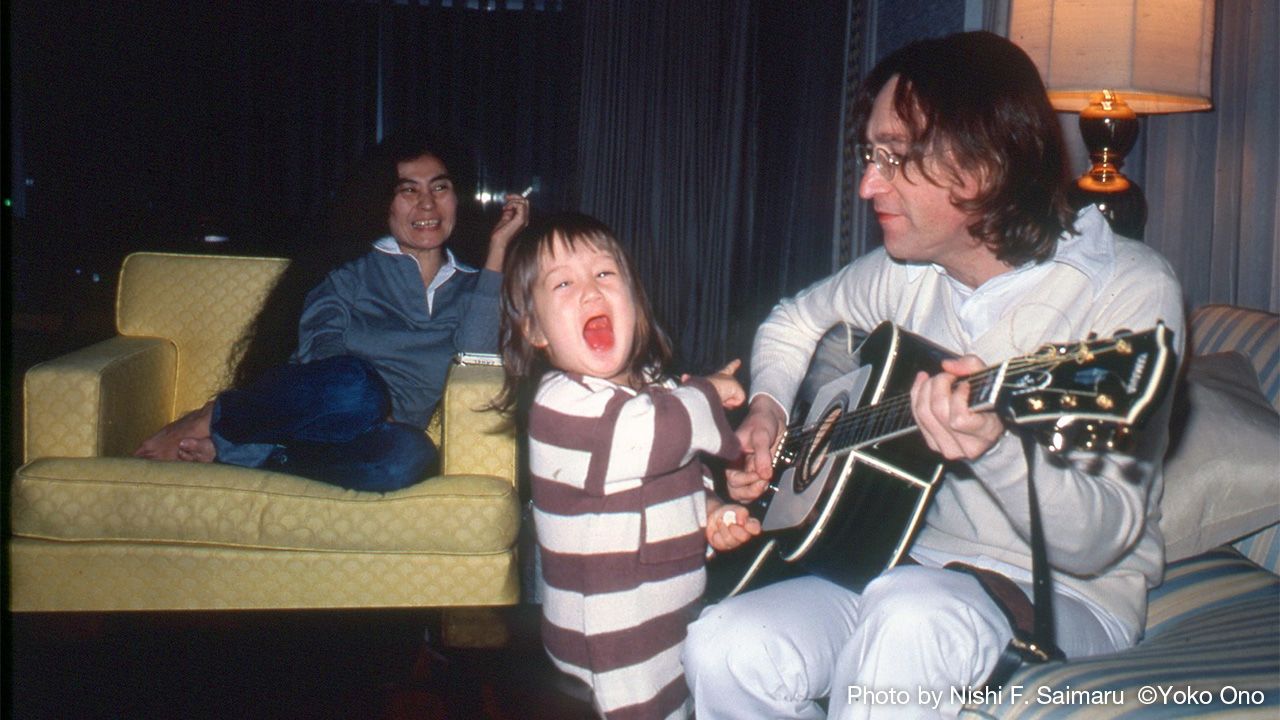

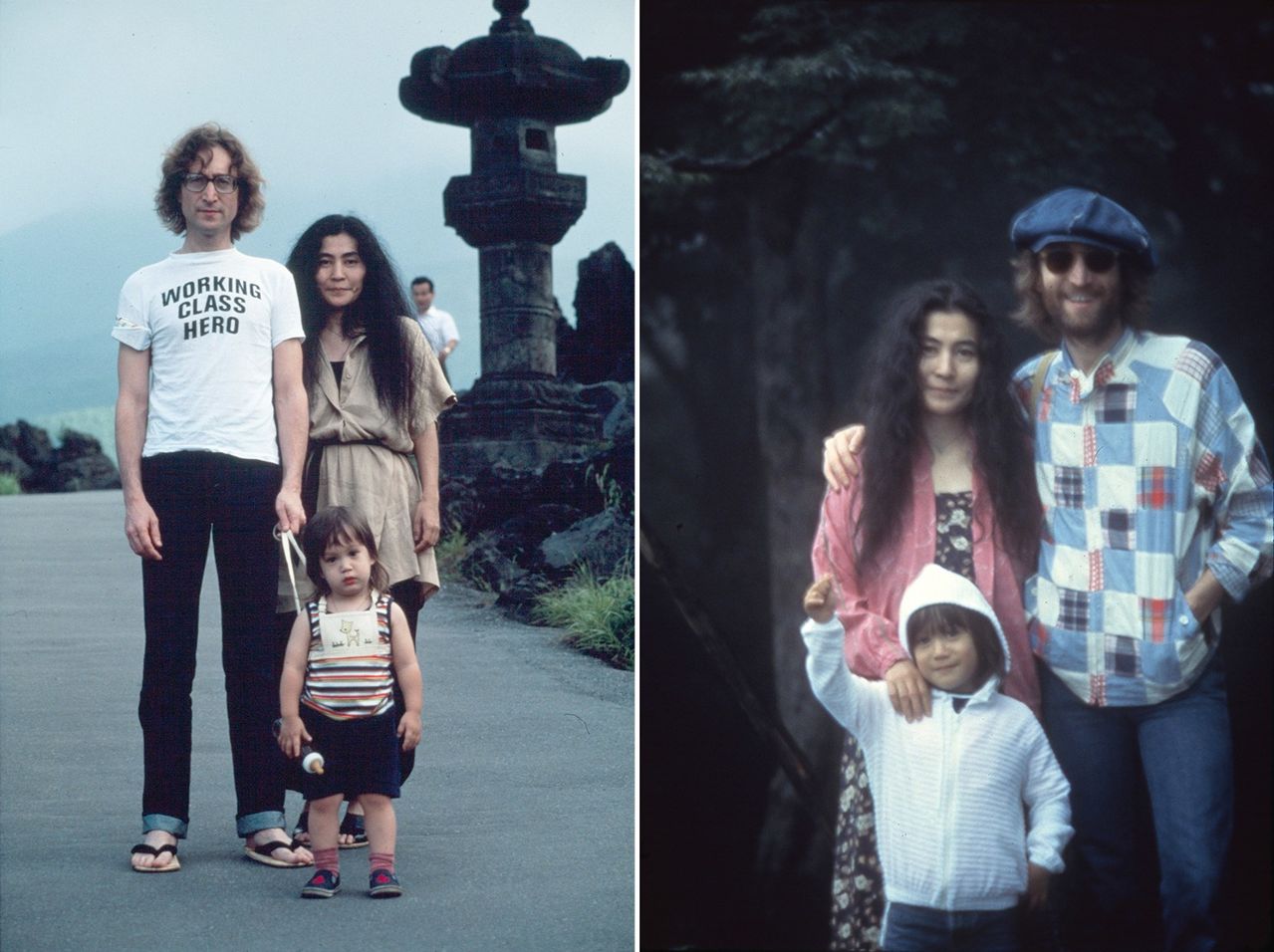

After a long battle, the deportation order was cancelled in October 1975. The couple’s only child, Sean, was born that month. The family went back to Japan again two years later, staying from May to October 1977. Including three months in 1978 and one more in 1979, they spent nine months in the country, moving between Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, Karuizawa in Nagano Prefecture, and Kyoto. There was talk that the couple was looking to buy a property in Japan as somewhere to relax and spend time out of the public eye.

“Nowadays, rumors of Lennon sightings would spread instantly across the country via Twitter. But in those days, we didn’t even know he was in Japan and the couple’s visit hardly made the news,” Hirota remembers.

“John announced that he was taking a break from music until Sean turned five, and devoted himself to the role of ‘househusband.’ The term is more familiar today, but back then it was more or less unheard of. I think John was the first prominent, influential man to dedicate himself to parenting in this way. He brought a yin-and-yang, Zen approach to his domestic role, too. It was Lennon who prepared the family’s meals, for example, practicing a macrobiotic diet built around brown rice and beans and based on the principles of yin and yang.

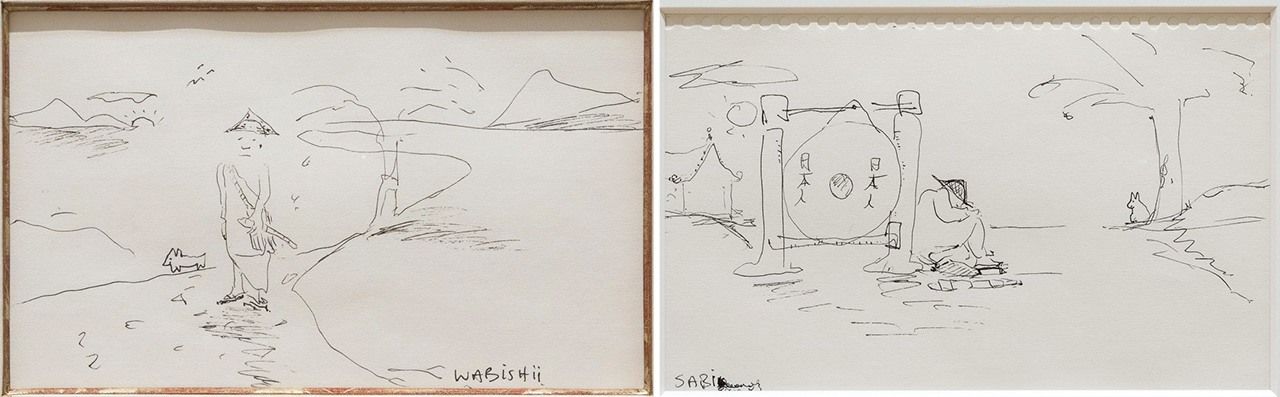

At the Double Fantasy: John & Yoko exhibition in Tokyo, visitors can see family photos taken in Japan along with drawings from Lennon’s sketchbook illustrating some of the Japanese words and phrases he was trying to learn. Some of the illustrations are reminiscent of Zen paintings.

John Lennon, Ono Yōko, and Sean Ono Lennon on holiday in Japan in the summer of 1977 (left) (photo by Nishi F. Saimaru; © Yoko Ono) and the family in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, in 1979 (photo by Nishi F. Saimaru; © Nishi F. Saimaru & © Yoko Ono). (Courtesy the Double Fantasy: John & Yoko exhibition in Tokyo)

Original pages from Lennon’s sketchbook: “Wabishii” and “Sabi.” Photos by Yamanaka Shintarō (Qsyum!). (Courtesy the Double Fantasy: John & Yoko exhibition in Tokyo)

Hirota recalls the joy he felt when the album Double Fantasy appeared after a five-year gap with no music. (The album was released in England on November 17, 1980). “When I listened to the advance tape that came from the record company, I was struck by the honest, realistic treatment of mature subjects like marriage, raising children, and the relations between the sexes. And then, just as we were all happily looking forward to hearing more of his music in the future, he was killed.

“When he spoke about his affection for Zen or haiku, it was more than just talk: he understood the philosophy and put it into practice it in the way he lived and wrote. Musicians like him are rare. If he had lived longer, he might have bought his holiday home in Japan and would have had more opportunities to interact with the country’s musical community and other artists. And I think he would have loved to be able to write haiku in Japanese. It was a real tragedy that that possibility was taken away from him.”

(Originally published in Japanese on November 20, 2020. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner photo: John plays guitar to Sean and Yōko, in Tokyo, Japan, in 1977. Photo by Nishi F. Saimaru. ©Yoko Ono. Courtesy the Double Fantasy: John & Yoko exhibition in Tokyo.)

No comments:

Post a Comment