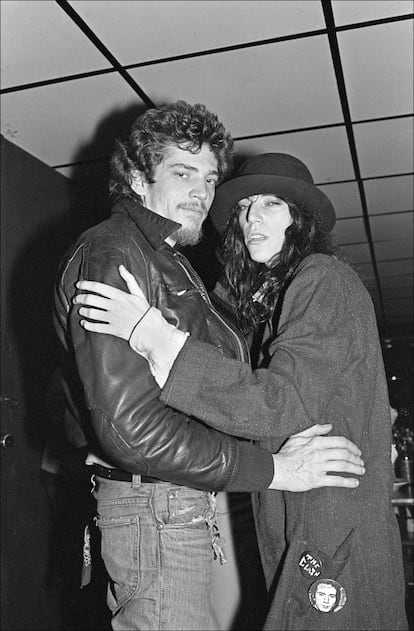

Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith: ‘If you don’t come, I’ll be with a guy’

‘Will you pretend you’re my boyfriend?’ she asked the artist, hoping to escape another man. That night, they stopped pretending. They shared a dazzling love story, marked by excess and art

Manuel Jabois

Sanxenxo, 14 August 2024

On July 3, 1967, 20-year-old Patricia Lee Smith arrived in New York wearing dungarees, a black turtleneck, an old gray trench coat, and a small red-and-yellow checked suitcase containing several notebooks, drawing pencils, and a copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, which was changing her already upturned life: pregnant at 19, she had put her baby up for adoption. Months later, in New York, she went to the address she had been given and there, in a room, she found a guy sleeping on an iron bed. “He was pale and slim with masses of dark curls, lying bare-chested with strands of beads around his neck […] He rose in one motion, put on his huaraches and a white T-shirt, and beckoned me to follow him […] I had never seen anyone like him,” she wrote 43 years later. The young man helped her to her room, and they said goodbye.

Days later, after getting her first job at one of Brentano’s bookstores in the jewelry and craft section, that guy appeared at the door. Wearing a white shirt and tie, this time, he looked “like a Catholic schoolboy.” He bought a necklace from Persia, Patti Smith’s favorite. As she wrapped it up, she blurted out, “Don’t give it to any girl but me.” He smiled and said, “I won’t.”

A week went by and Patti Smith, hungry and with no place to sleep (she slept secretly in the store, on her coat, when everyone else left: she waited and locked in the bathroom), accepted an invitation to dinner from a writer who had been hanging around the bookstore for days and watching her. She forgot her mother’s advice (don’t go anywhere with a stranger) driven by hunger. The two had a big, expensive dinner, and once outside, the writer invited her to come up for a drink. Desperate, she looked for a line of escape. Out of nowhere appeared the boy from the iron bed, the boy with the Persian necklace. She went to him: “Will you pretend you’re my boyfriend?” she asked. They spent the night together, side by side and talking non-stop (“I was surprised at how comfortable and open I felt with him. He told me later that he was tripping on acid”). They slept in each other’s arms and never separated again. He pretended until the end.

He told Patti his name that night, Bob, but she decided that Bob didn’t suit him, so she called him Robert. Robert Mapplethorpe, that was his real name. His stage name, too, because this is a story about absolute love between two 20-year-olds who, in time, would become two legends of the 20th century. But that last bit doesn’t matter.

In Just Kids — a momentous book in which she analyzes their abrasive and unusual relationship — Patti Smith writes that she was a bad girl obsessed with behaving well; while he was a good boy, who really wanted to behave badly. They depended on the generosity of Robert’s friends to sleep under a roof. To save money, Patti skipped meals (a coworker, worried about how thin she was, she started leaving a lunchbox with soup in the closet) and although, she writes, she never questioned the decision to give her child up for adoption, “I learned that to give life and walk away was not so easy.” She cried so much that Robert called her Soakie. She had, she says, such narrow hips that carrying a child had literally opened the skin of her belly. The first time they slept together, Robert could see the stretch marks that crisscrossed her abdomen.

What happened between them and around them, under them and above them, is a story so amazing and dazzling that this article can only bear poor testimony to its beginning and its end. In between, Patti Smith would become a composer, singer, writer, and Robert Mapplethorpe, who was painting when he met Patti, would become a famous photographer. They lived together in the Chelsea Hotel at a time — 1969 — when Andrea Feldman, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Dylan Thomas and Allen Ginsberg lived there or passed through the hotel. As did Jim Carroll, the poet (junkie, hustler, everything) who wrote about his life in The Basketball Diaries, which was later tuned into a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio. “How do you know you’re not gay?” Robert once asked him. “Because I always ask for money,” Carroll replied. When Patti and Robert began to have a more intimate, friendly, less sexual relationship, she began dating Sam Shepard.

Robert confronted her one day. He wanted to take her with him to San Francisco. “I have to find out who I am,” he said. She refused. He insisted: “If you don’t come, I’ll be with a guy. I’ll turn homosexual.” And Patti didn’t understand: “There was nothing in our relationship that had prepared me for such a revelation. All of the signs that he had obliquely imparted, I had interpreted as the evolution of his art. Not of his self.”

“I’ve been accused of dressing like a hustler, having the mind of a hustler and the body of one,” he wrote to her months later, still shocked by Midnight Cowboy, a movie about an unlikely friendship between two hustlers. “He felt a deep identification with the hero, infusing the idea of the hustler into his work, and then into his life,” Patti wrote. “Hustler-hustler-hustler. I guess that’s what I’m about,” he said. (Years earlier, he had taken up prostitution to pay their rent.)

In February 1989, many, many years later, Robert Mapplethorpe, who was HIV positive, met Patti Smith with his nurse. There he asked her a devastating question: “Patti, did art get us?” “I don’t know, Robert. I don’t know.” “Patti, I’m dying. It’s so painful.” And she knew, for the first time, that the 20-year-old boy she had met when he was poor, disheveled, happy tripping acid, the boy who had been with her all her life, was going to die.

They were still together, they always stayed together in their own way, even making love. “Separate ways together,” Patti summed up. Robert took an iconic photograph of the singer: the cover of Horses, Patti Smith’s first album. “This one has the magic,” he said, choosing one from the selection. “When I look at it now, I never see me. I see us,” she said.

A month later, she called the hospital as she did every night to wish him good night. But the morphine had put him to sleep, and Patti stayed on the phone listening to his labored breathing, suspecting that she would never hear his voice again. She put her things away on the desk, which had also been Robert’s, tucked her children in, went to bed with her husband, telling him: “He’s still alive,” and then prayed. When she woke up and went downstairs, in the silence of the house, she learned that Robert Mapplethorpe had died. Minutes later, the phone rang. Patti Smith remembers that the Tosca aria Vissi d’arte was playing on the television: “I have lived for love, I have lived for Art.”

No comments:

Post a Comment