Mishima Yukio’s Suicide and “The Sea of Fertility”

Half a century after Mishima Yukio’s suicide, literary specialist Inoue Takashi considers the connections between his death and his final work, Hōjō no umi (trans. The Sea of Fertility).

On November 25, 1970, Mishima Yukio handed the manuscript for the final part of his tetralogy Hōjō no umi (trans. The Sea of Fertility) to his editor. The same day, after an attempt to rouse Self-Defense Forces troops to rebellion foundered, he performed seppuku in the commander’s office at the headquarters of the Ground SDF Eastern Command in Ichigaya, Tokyo. One of his followers assisted his ritual suicide by chopping his head off. Thus, Mishima’s last work and his life finished at the same time. The shocking nature of the event is still being discussed across the world half a century later. But the events in the lead-up to his death are surprisingly little known. When did Mishima decide to kill himself? And what was the connection to his literature?

Mishima wrote repeatedly about death from his earliest works. In the short story “Misaki nite no monogatari” (A Story at the Cape), which he wrote at the age of 20 in 1946, just after Japan’s surrender, a young boy lost in the mountains by the sea meets a beautiful young couple before their double suicide, and feels his own growing attraction to death. In the 1961 story “Yūkoku” (trans. “Patriotism”), a lieutenant agonizes with his wife over the prospect of fighting against other officers in his unit to suppress the attempted coup d’état of 1936 that later became known as the February 26 Incident. The 1966 film adaptation by Mishima saw the author himself playing the part of the lieutenant, who ends his life by seppuku. In 1968, he formed a private army of students called the Tate no Kai (Shield Society)—members of the group would witness his last moments in the commandant’s office—and from this point, there are indications that he was ready to die at any time.

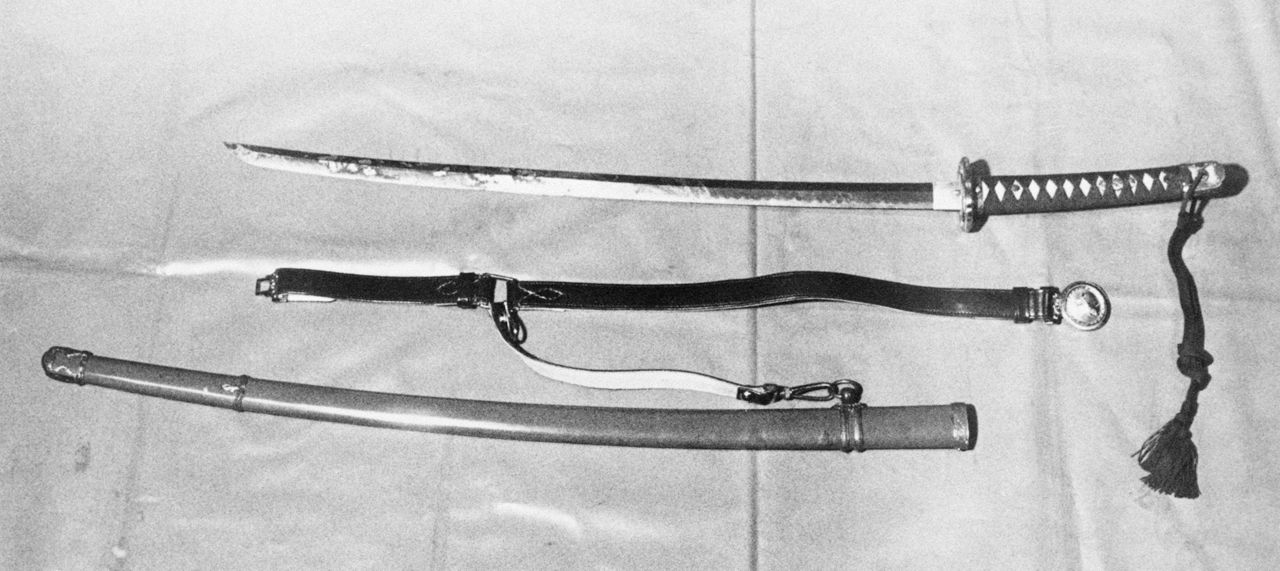

The sword used by Mishima Yukio in his suicide and its scabbard. (© Jiji)

However, it is one thing to depict death, perform death, and prepare oneself mentally for death; it is quite another to actually end one’s life. Even in January 1970, the year of his suicide, Mishima spoke of writing a historical novel on the poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241) after he completed The Sea of Fertility. At this point, he seemed not to have resolved to die in November. Although descended from the powerful statesman Fujiwara no Michinaga (966–1027), Teika was politically obscure, but idolized in the literary world. There is some reason to believe that Mishima considered this as a stance for himself to imitate. In the end, however, he rejected it and abandoned the planned novel. What happened to make him do this?

Mishima Yukio’s body is transported out the commandant’s office at the headquarters of the Ground SDF Eastern Command in Ichigaya, Tokyo. (© Jiji; pool photo)

Hints from Mishima’s Last Work

In each of the four books of The Sea of Fertility, the protagonist appears as a different incarnation. The 1967 opener Haru no yuki (trans. Spring Snow) is a love story centered on a young aristocrat in the Taishō era (1912–26). Matsugae Kiyoaki begins a relationship with Ayakura Satoko, who is engaged to an imperial prince, and makes her pregnant. She has an abortion and becomes a nun, while he dies of illness without ever meeting her again.

However, Kiyoaki is reborn as Iinuma Isao in the 1968 sequel Honba (trans. Runaway Horses), a story of nationalism and terrorism set in the early Shōwa era (1926–89). Iinuma assassinates a powerfully manipulative financier and then kills himself through seppuku.

In the 1970 third book, Akatsuki no tera (trans. The Temple of Dawn), Kiyoaki’s close friend from the first book, Honda Shigekuni—who appears in each part—is now an aging lawyer who acts eccentrically, stalking a Thai princess known as Ying Chan, the reincarnation of Iinuma. His twisted affections come to nothing, and Ying Chan dies in her own country, while Honda lives on. Mishima handed over the novel for editing on February 20, 1970.

After that, Mishima took a two-month break from serial publication, spending the time pondering the plot of the fourth and final book. One idea was to have the elderly Honda meet several claimants to be the latest reincarnation, and find them to be false. In the end, though, he would find the true reincarnation and die happy. Another plan was to have him enter a confrontation with a pretender, although this was followed by the same encounter with the true reincarnation and subsequent joyful death. Mishima’s notes indicate that he thought he would need a year and four months to write the book along these lines, which would mean completion around July 1971. At this stage then, he was not thinking of dying in November 1970.

However, the above plan was nothing like the ending of the fourth book Tennin gosui (trans. The Decay of the Angel), in the version published in 1971, after Mishima’s death. In this novel, Honda adopts a young man called Yasunaga Tōru, who he believes to be the latest incarnation. After learning he is not, he goes to meet Satoko, first introduced in Spring Snow, who since renouncing the world has become an abbess. She tells him that she never knew anyone called Matsugae Kiyoaki, suggesting that he never existed, and rejects Honda’s story of reincarnations. Flabbergasted, Honda senses his own identity starting to slip away. He is shown to the nunnery garden, in which the cries of cicadas reverberate, and feels he has come to a place where there are no memories—indeed, nothing at all. The loss of memory could also be called a loss of life. This is where the tetralogy ends.

Feeling Stifled

Mishima’s notes suggest that he scrapped his original structure and began to think of the final version of the plotline for The Decay of the Angel around March or April 1970. Records from the trial that followed the attempted coup show that he started planning the uprising at a similar time. This means that he was preparing himself for death while he was adjusting the plot of The Sea of Fertility from a happy to a negative ending.

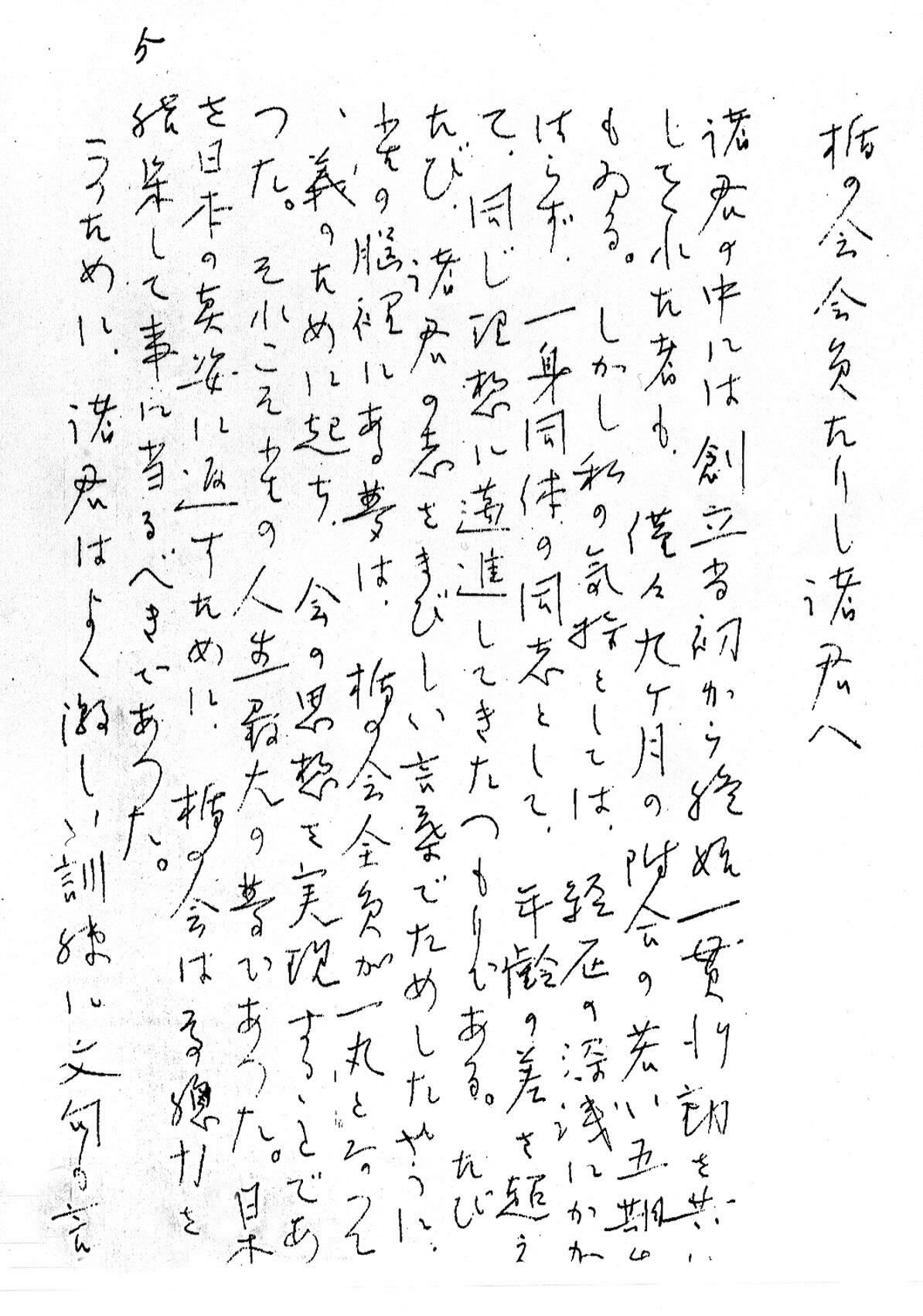

Mishima Yukio’s will, addressed to the Tate no Kai (Shield Society) before his death. (© Jiji)

What is the significance of this timing? During Japan’ high-growth years in the 1960s, Mishima seemed to have the world at his feet, making performances on the big screen and glamorous poses in magazines. This was just on the surface though. As Japanese society became more equal, values became increasingly standardized and though apparently free, in fact everyone came to have a similar outlook on life. Mishima felt stifled. When it came to his novels, after Kinkakuji (trans. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) in 1956, works like jos 1959 Kyōko no ie (Kyōko’s House) and 1960 Utage no ato (trans. After the Banquet) were not particularly well received. The dark tone of Honda’s repeated follies in The Temple of Dawn and the multitude of fake reincarnations in the planned fourth book reflect Mishima’s insight into the truth of the age, and the pains of living then.

Nonetheless, the original ending in which Honda met the true reincarnation before his happy death showed that Mishima still believed in the possibility of redemption in life. If so, does his about turn mean he had abandoned that belief? The final part of The Sea of Fertility refrains from offering a vision of relief that does not actually exist, instead clearly and unflinchingly depicting the awful truth. This must have been how Mishima saw it. But what prompted the decision? This is equivalent to asking why he chose to die. With various points at issue, it is impossible to reach a firm conclusion, but I want to touch on a historical point that tends to be passed over.

From March 15, 1970, the World Exposition was held in Osaka. Together with the Tokyo Olympics of 1964, it represented the attainment of Japan’s postwar recovery. But Mishima saw this as nothing more than affectation, and a kind of fallaciously shining vision that needed to be torn away. This is the motif for The Decay of the Angel, and was the basis for his censure of the age through his own death. Mishima saw the completion of his life and literary works as part of the same thing.

A Vision of Twenty-First Century Japan

When Mishima died in 1970, Japan was still enjoying an economic boom, and for those readers at the time without a shred of doubt about the bright outlook, his sense of urgency at the seriousness of the situation was inexplicable. To them, his seppuku seemed nothing other than anachronistic and foolish, while the nihilistic conclusion to The Decay of the Angel was an act of creative bankruptcy. But the half a century that has passed since then has seen Japan change dramatically. We have witnessed a succession of disasters: the Aum Shinrikyō subway attacks; the Great East Japan Earthquake, and the subsequent tsunami and nuclear accident; and now the COVID-19 pandemic. The sense of doubt that Japan’s economic growth and postwar recovery—or even modernization itself—may actually have been a sham construction has grown day by day. Perhaps The Decay of the Angel predicted the Japan of the twenty-first century. This is what I believe.

The US author Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007) described the artist’s role as like “the canary in the coal mine,” reacting early to any deterioration in the quality of the air. By analogy, great artists are sensitive to the spirit of the age, and are first to sound a warning to society. The readers of Mishima’s time were indifferent to the message he staked his life on, but can we in the present—tormented by a sense of nothingness with no way out—receive directly the message he tried to convey?

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Mishima Yukio gives a speech from a balcony at the headquarters of the Ground SDF Eastern Command in Ichigaya, Tokyo, on November 25, 1970. © Jiji.)

Professor at Shirayuri University. Specializes in Mishima Yukio and other modern Japanese literature. Born in Yokohama in 1963. Graduated from Tokyo University, where he also conducted graduated work. Was a lecturer and associate professor at Shirayuri University before taking on his current position in 2008. Works include Mō hitotsu no Nihon o motomete: Mishima Yukio Hōjō no umi o yominaosu (Seeking Another Japan: A Reassessment of Mishima Yukio’s The Sea of Fertility) and Mishima Yukio Hōjo no umi vs. Noma Hiroshi Seinen no wa: Sengo bungaku to zentai shōsetsu (Mishima Yukio’s The Sea of Fertility vs. Noma Hiroshi’s Ring of Youth: Postwar Literature and the Total Novel).

No comments:

Post a Comment