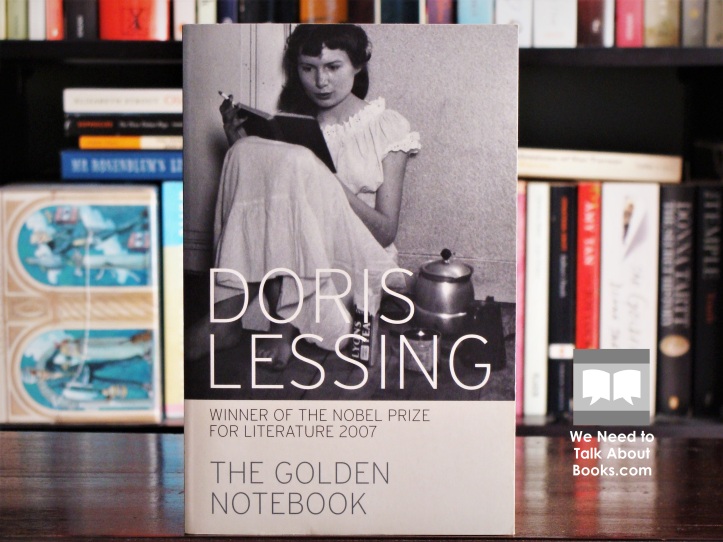

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing

[A Review]

First published in 1962, The Golden Notebook, by Nobel Prize Winner Doris Lessing, brought to the surface the unheard stories of an underclass of women mistreated by the men who have power over them, a time of dissolving political certainties and of constant fear of nuclear war.

The Golden Notebook is the story of Anna Wulf; a divorced single mother, struggling writer and former communist living in London in the late 1950’s. Anna’s marriage was brief and lacked physical attraction and emotional intimacy. But she is thankful at least for the daughter she got out of it. Anna has had other relationships over the years since her divorce; invariably with married men, which never last.

She has been able to support herself with the proceeds from her novel, a best-seller called Frontiers of War. The novel is based on Anna’s youth in Colonial Africa during WWII. It centres around a group of young, white, idealists and their political debates and hypocrisies particularly around communism, racism and the war. With the proceeds Anna has been able to buy a house in London for her daughter and herself with room for a tenant.

Anna has only one close friend; Molly. Like Anna, Molly is a divorced single mother and a disillusioned communist. A minor actress, Molly too is supporting her son and herself on the fickle income of an artist. While Molly has regular arguments with her ex-husband, Richard, she is also increasingly anxious about their adult son, Tommy, who seems broody and apathetic.

Lately, Anna feels her life is rapidly unravelling; she is struggling to keep her head above water and fears she may be close to losing her sanity.

She went to the nearest underground, not-thinking, knowing she was in a state of near-collapse. The rush hour had begun. She was being jostled in a herd of people. Suddenly she was panicking, so badly that she withdrew from the people pressing towards the ticket booth, and stood, her palms and armpits wet, leaning against a wall […] Something is happening to me, she thought struggling for control […] She was thinking: If someone cracks up, what does that mean? At what point does a person about to fall to pieces say: I’m cracking up? […] She shut her eyes, seeing the glare of the light on her lids, feeling the pressure of bodies, smelling sweat and dirt; and was conscious of Anna, reduced to a tight knot of determination somewhere in her stomach. Anna, Anna, I am Anna, she kept repeating.

Anna became a communist in her youth because she felt they were the only group that expressed a strong moral outrage at the inequities of the status quo. However, in recent years, as the reality of Stalin became apparent, as the horrors of life behind the Iron Current became known, as the threat of nuclear annihilation became real and as the stubbornness of the British Communist Party to acknowledge such facts became farcical, Anna and Molly became strongly disillusioned and cut their ties to the Party. The experience left Anna ideologically lost and adrift. She now only uses the word ‘comrade’ with nostalgic irony.

Meanwhile, the proceeds from her novel, her main source of income, are drying up. She has not been able to complete another novel. Some days she feels embarrassed by her bestseller, feeling it was a poor novel of a naïve novice. Some days she wants to write again but can’t get past her crippling writer’s block. Other days she denies she ever wants to write again.

Though Anna values her friendship with Molly, it is complicated. Molly’s whole life is complicated with her battles with her ex-husband and wayward son and Anna frequently finds herself caught between them, being asked to referee or advocate. It is a source of stress Anna really does not need right now.

Adding to that stress, Anna’s current tenant, Ivor, and his lover, Ronnie, who’s moved himself in, are slowly taking over her house while neglecting to keep up with their rent payments. They both make Anna feel intimidated and unwelcome in her own home. Meanwhile, Anna’s daughter, Janet, is growing up and yearning for normalcy. Janet does not admire or respect her unemployed, former communist, unmarried mother as any kind of pioneer or revolutionary; or ‘new woman’ as Anna puts it. Janet does not believe she would make the same choices as her mother and wishes her home life was something much more traditional.

On top of all this lies Anna’s disappointments in love. Particularly a break up with Michael, a married man she lived with for five years. It has been three years since they broke up, but she met him recently and is clearly not yet over the hurt of their break up.

She sat up in bed in the big dark room, smoking, and felt herself as vulnerable and helpless. […] A week ago, coming home late from the theatre, a man had exposed himself on a dark street corner. Instead of ignoring it, she had found herself shrinking inwardly, as if it had been a personal attack on Anna – she had felt as if she, Anna, had been menaced by it. Yet, looking back only a short time, she saw Anna who walked through the hazards and ugliness of the big city unafraid and immune. Now it seemed as if the ugliness had come close and stood so near to her she might collapse, screaming.

And when had this new frightened vulnerable Anna been born? She knew: it was when Michael had abandoned her.

Before we go any further we must discuss the elephant in the room; the structure of The Golden Notebook.

We read the story of Anna in The Golden Notebook in two main forms. The first is a fairly standard telling; a third-person short novel called Free Women which is divided into five parts. The second is a first-person narration by Anna that comes in the form of her diaries or notebooks – she has four of them. In the black notebook she writes about her writing life, in the red notebook about her political life, in the yellow notebook about her ‘emotional life’ and in the blue notebook about everyday events.

Essentially, Anna’s note keeping is a form of self-therapy. She hopes that by compartmentalising her life she might better stay on top of it. When reading The Golden Notebook, we are first given part one of Free Women, followed by excerpts from each of the notebooks in turn – black, red, yellow, blue. This repeats for four cycles. After we read the fourth excerpt from the blue notebook, we are given a new notebook – the golden notebook – followed by part five of Free Women which completes the novel. As well as being third-person, Free Women is set in the ‘present’ as far as the reader is concerned while the notebooks are set in the past but as we move through the cycles, the gap between them closes until they become contemporaneous.

The descriptions of the four notebooks I gave above are similar to that given in the blurb and elsewhere in the book, but they aren’t entirely accurate. The black notebook, for instance, has very little of what you might expect from a descriptor like ‘writing life’. Mostly it is Anna telling us about the real events from the period of her life in Colonial Africa that inspired her novel.

Otherwise in the black notebook, Anna is telling us about the encounters she has had with various people who want to adapt her novel for television, film or the stage. Despite her dwindling income, Anna has little difficulty turning down such offers since the people making them clearly do not understand her novel. They want to relocate the story from Africa, focus on the love story aspects and ignore the fact the novel was mostly about racism.

The red notebook is fairly described as containing Anna’s political life. Anna chronicles her experiences within and outside of the Communist Party; the people she was involved with, including Michael; the major events that occurred such as the Rosenbergs, the death of Stalin and his denouncement at the 20th Party Conference; the impact of the Hungarian Revolution with its executions and the fate of Russia’s Jews.

The yellow notebook, which was described as being about Anna’s ‘emotional life’, is actually an attempt to write stories out of her experiences, mostly in the form of a short novel called The Shadow of the Third. This novel is about Ella, a writer for a magazine who, like Anna, is a divorced single mother with one close friend; Julia. Like Anna, Ella has an affair with a married man, a psychologist named Paul, which initially fulfilled her before its failure threatened to destroy her.

The blue notebook was meant to serve as a more traditional diary. It recounts meetings with Molly and others in her life, sessions with her psychiatrist, clippings from newspapers, etc.

If all this sounds terribly complex, I suppose it is, but, for the most part, it is actually quite easy to read. Where I got stuck was when I found myself getting quite invested in the story of Ella and Paul before reminding myself that they are ‘fictional’ from Anna’s point of view since they are characters in her novel, The Shadow of the Third. This led to me asking myself what is Anna saying about herself and Michael through the story of ‘Ella’ and ‘Paul’? That was when my head began to swim, which is not what you want. I think the relationship between the ‘fictional’ Ella and Paul and the ‘real’ Anna and Michael is key to the novel, but it was far too difficult for me to interpret at the time of reading. I could only do so on reflection once I had finished the novel.

There is a nesting aspect to The Golden Notebook – with Free Women and the notebooks, with Anna and Ella – and it can be easy to lose your bearings. I found myself wondering at what level is the story ‘real’? ‘Ella’ isn’t real if she is a character in Anna’s story, but Ella’s story may have ‘real’ things to say about Anna. Anna’s experiences in Africa are ‘real’ but she had turned them into fiction for her novel. The notebooks are real, but since they are first-person, should we trust what Anna says in them? And what of Free Women should you trust?

If all this complexity is starting to turn you off, again, it was hardly a concern when reading, only later on reflection.

There is another layer of nesting to consider. Lessing’s writing is known to be very autobiographical. Like Anna, at the time of writing, Lessing was also a divorced single mother, a disillusioned communist, and the writer of a best-selling first novel set in Colonial Africa during WWII (The Grass is Singing).

What ‘Anna’ may have to say about Lessing is not something I dwelt on, but reading The Golden Notebook and learning of Lessing’s writing methods did make me wonder what is left to discover in her other novels. For example, I was eager to read her novel The Good Terrorist as I understood it to be about political disillusionment, radicalism, ideology, etc. But there is so much of that in the red notebook, and well done, that I wonder what is left for The Good Terrorist. Reading The Golden Notebook also made me keen to read her first novel, The Grass is Singing, but, again, I wonder what is left to discover after reading so much in the black notebook. I will probably still read both anyway.

The edition of The Golden Notebook I read, published by Harper Perennial, includes a preface written by Lessing in 1971, the transcript of a short interview with Lessing and another short introduction by Lessing. A consistent theme in each of these is the matter of how The Golden Notebook was received when first published in 1962.

Lessing is adamant that she did not set out to write a ‘feminist’ novel or anything of the sort. Lessing simply set out to write about women like herself and many others she discovered going door-to-door for the Communist Party.

For example, I had a woman friend at the time who was very bitter about men, in a way I don’t think women are now. She was a single women, and she wanted a bloke, and she wanted to be married. But she was always having affairs with married men, and she was angry with them. Yet she was living the kind of life that invited it. I was interested in that – Lessing.

Women who enjoy a certain sense of liberty, especially compared to women of previous generations, yet are also somewhat trapped, purposeless, unfulfilled and still do not enjoy the same freedoms as men, some of whom mistreat them.

Being so young, twenty-three or four, I suffered, like so many ‘emancipated’ girls, from a terror of being trapped and tamed by domesticity. George’s house, where he and his wife were trapped without hope of release, save through the deaths of four old people, represented to me the ultimate horror. It frightened me so that I even had nightmares about it. And yet – this man, George, the trapped one, the man who had put that unfortunate woman, his wife, in a cage, also represented for me, and I knew it, a powerful sexuality from which I fled inwardly, but then inevitably turned towards. I knew by instinct that if I went to bed with George I’d learn a sexuality that I hadn’t come anywhere near yet. And with all these attitudes and emotions conflicting in me, I still liked him, indeed loved him, quite simply, as a human being.

In particular, women who – like Lessing, Anna, Molly, Ella and Julia – are single mothers, preyed upon by married men who see them as fair game for affairs. Women who sometimes consent to be mistresses to such men for varied reasons from loneliness, boredom, love and sexual frustration.

He says goodbye to Ella, remarking: ‘Well, back to the grindstone. My wife’s the best in the world, but she’s not exactly an exhilarating conversationalist.’ Ella checks herself, does not say that a woman with three small children, stuck in a house in the suburbs with a television set has nothing much exhilarating to talk about. The depths of her resentment amaze her. She knows that his wife, the woman who is waiting for him miles away somewhere across London will know, the moment he enters the bedroom, that he has been sleeping with another woman, from his self-satisfied jauntiness.

These affairs both tarnish friendships between these women while also creating common bonds between them.

As for Anna she was thinking: If I join in now, in a what’s-wrong-with-men session, then I won’t go home, I’ll stay for lunch and all afternoon, and Molly and I will feel warm and friendly, all barriers gone. And when we part, there’ll be a sudden resentment, a rancour – because after all, our real loyalties are always to men, and not to women…

This aspect, of older single women having affairs with married men, put me to mind of Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick:

When you sleep with a married man you in a sense sleep with the wife as well, so she should no be an utter embarrassment – The Witches of Eastwick

In hindsight, Lessing could see how the novel would inevitably be interpreted for what it had to say about women and men.

Emerging from this crystallising process, handing the manuscript to publisher and friends, I learned that I had written a tract about the sex war, and fast discovered that nothing I said then could change that diagnosis.

Yet the essence of the book, the organisation of it, everything in it, says implicitly and explicitly, that we must not divide things off, must not compartmentalise – Lessing.

Lessing found her novel was denounced and championed respectively by the sides forming in the battle of the sexes, with both sides perhaps guilty of seeing in the novel only what they wanted to see.

Ella finishes her novel and it is accepted for publication. She knows it is quite a good novel, nothing very startling. If she were to read it she would report that it was a small, honest novel. But Paul reads it and reacts with elaborate sarcasm.

He says: ‘Well, we men might as well just resign from life.’

She is frightened, and says: ‘What do you mean?’ Yet she laughs, because of the dramatic way he says it, parodying himself.

Now he drops his self-parody and says with great seriousness: ‘My dear Ella, don’t you know what the great revolution of our time is? The Russian revolution, the Chinese revolution – they’re nothing at all. The real revolution is, women against men.’

‘But Paul, that doesn’t mean anything to me.’

But the novel, and reality, is far more complex. Molly’s communist sympathies may lead her to view her businessman ex-husband’s life with contempt, yet, she also relied on him to fund the education she wanted for their son and expects her ex to use his position to help create opportunities for their son. She shows no interest in being financially independent herself, even for her son’s benefit, but prefers to try her hand at painting, acting and dancing while avoiding putting any real effort, or offering any commitment, to any vocation. Instead she always expects a new marriage to be just around the corner that will resolve any financial woes. Her pride in being an independent and free woman, therefore, is somewhat contradicted and confined, partly by the inequities of the world she lives in, but partly by her own actions and beliefs as well.

In the novel, Anna shows she is aware of this complexity. The novel compares the feelings of women towards the misogyny and chauvinism of the men in their lives with the position taken by the British Communist Party to events in the communist world and the attitudes of whites in Colonial Africa towards racism and Hitler. In each case there are those who have integrity and those who are hypocritical, those who are victims and those who are complicit.

This war was presented to us as a crusade against the evil doctrines of Hitler, against racialism, etc., yet the whole of that enormous land-mass, about half the total area of Africa, was conducted on precisely Hitler’s assumption – that some human beings are better than others because of their race. The mass of the Africans up and down the continent were sardonically amused at the sight of their white masters crusading off to fight the racialist devil […] They enjoyed the sight of the white baases so eager to go off and fight on any available battle-front against a creed they would all die to defend on their own soil.

The novel and its characters, like the real-world issues, are therefore more complex and nuanced than those early interpreters were perhaps open enough to see. Lessing’s intention may have been aimed more at providing realism than any social allegory.

Timing also had a significant role to play in how the novel was received, with it being published just in time to catch the second wave of feminism; just a year before Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published. The novel is at times quite graphic and explicit when it comes to sex and bodily functions. I imagine this would have been quite shocking for the time and may be an area where we see the influence of Joyce.

Lessing laments that there is much else in her novel, besides sexual politics, that gets overlooked. Themes such as the struggles of artists, political disillusionment, art and culture, madness and psychotherapy (The Golden Notebook was also published the year before Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar). In particular, Lessing feels her modernist experimentation with the style and structure of the novel barely gets mentioned.

There were a few things I did not enjoy about The Golden Notebook. The major one was that, as we come to the fourth part of the blue notebook, the first-person story of Anna slips into stream-of-consciousness – another area where we see the influence of Joyce. The technique has an obvious purpose – it shows the reader how Anna is losing her grip, coming dangerously close to losing her sanity. While, admittedly, there were some very fine passages in this section, it made for difficult and unenjoyable reading for me just at the time the story is reaching its apex.

Given the structure of the novel – with the Free Women novella and the notebooks – and the content – with Anna and Ella both being writers, the stories from various episodes of each of their lives, etc – it might be tempting for someone who has not read The Golden Notebook to assume that it sounds like a patchwork novel; consisting of writings Lessing abandoned and then stitched together to make this novel. For the most part I would say this is untrue and unfair. Even if the sources of various content in The Golden Notebook came from other attempted writing of Lessing’s, she has succeeded in creating a fairly seamless whole.

There were some exceptions. The fourth iteration of the yellow notebook was mostly a list of story ideas Anna noted down. This was a moment I felt the stitch work was showing in an otherwise well put together novel. There were also some passages in the novel – such as some of the lengthy parts set in Africa, or the story of Molly’s son – that I did not really see the point of, but it could be that I failed to understand them. As the number of men Anna/Ella has affairs with keeps growing, some of the later ones felt a bit forced; as if Lessing had more she wanted to say about men and their behaviour but needs Anna/Ella to have more affairs with men of different characters and backstories in order to say it.

I also have to ask whether the novel has aged well. How could it not? It details a time when political certainties were dissolving, nuclear war was a real threat and it brought to the surface the unheard stories of an underclass of women mistreated by the men who have power over them – sounds very relevant! Despite this, The Golden Notebook felt very much of its time. I think its appeal in this regard is mostly weighted towards giving the reader an understanding of the issues of that time rather than having much to say about ours. History does not repeat, but it does rhyme, as Mark Twain noted.

I wanted to capture the flavour of 1956 and later, and I think I did. The novel could not be written now – Lessing.

The parts of the novel I liked best were the parts that were relevant and relatable. As mentioned, it has some obvious parallels to the times we presently live in but, beyond that, I found things I could relate to personally as well. Despite Lessing saying the novel was ‘meant for women’, as a stay-home parent to a young child I could certainly relate to some of the challenges the characters face.

Despite a few eccentricities and the fact that it is a somewhat difficult novel, I think The Golden Notebook ought to be read more widely. While it is very much of its time, its success in capturing that time means it offers a current reader a window to a past we should remember. The resonance of the issues it raises forces us to ask questions about our own time and its relation to the past and the future. It is a novel that has much to say which we would benefit from hearing.

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT BOOKS

No comments:

Post a Comment