This is one of my occasional series where I share my thoughts on the whole of a book, so if you don’t want to know how it ends, look away now …

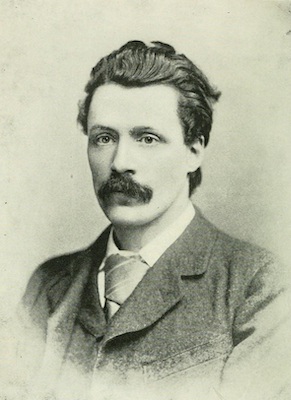

New Grub Street was first published in 1891 but its account of the struggles of a group of London writers resonates today.

The novel opens with aspiring writer Jasper Milvain lamenting to his family that his friend and fellow author Edwin Reardon has made the terrible error of marrying for love. Reardon’s new wife, Amy, is from a comfortable background, and his delicate constitution and literary sensibilities mean he will be incapable of making enough to support her.

Milvain then contrasts the advance Reardon has got for his book with how he would have exploited his book (if only he had actually written one), exploiting international rights and the burgeoning periodicals market through the new technology of the telegraph.

The growth of the periodicals market and the rise of mass literacy created a change comparable to the way that the rise of the ebook brought a whole new way for authors to make money — or more often fail to — as self-publishers. This conversation could easily take place today, except Milvain would be talking about audio rights and subscription royalties and direct sales. The title of the book in turn looks back to a previous similar era – referring as it does to the Grub Street which was home to impoverished hack writers as far back as the seventeenth century.

Milvain likes to see himself as hard headed. He is ambitious and aware of the challenges of the market. But he soon makes the mistake of falling in love with a cousin of Reardon’s wife. Marian Yule is intelligent, thoughtful and represents the woman he would marry if money was not a factor. Sadly, it is, and Marian’s own family offers a warning.

Her father is from a previous generation of respected but unsuccessful writers for periodicals. He married a woman outside his class because his low income meant it was either that or remain single. Marian works alongside him as writer and researcher (while he gets the credit) while her mother is both estranged from her own class, and painfully self-conscious around her husband and daughter because of her lack of learning. Marian’s father relies on both his daughter’s labour and his wife’s housekeeping without showing either much appreciation or affection.

Meanwhile, Reardon is suffering. He cannot repeat the literary success of his first novel, and financial worries leave him feeling depressed and unable to concentrate. Reardon’s wife, Amy, grows weary of his protestations. She wants him to write something commercial. What can be so hard? She does not understand why he can’t simply turn out a few pages a day of whatever the market requires.

He makes the attempt but he fails. He is doubly damned: he despises what he has written, but also fails to hit the right notes to succeed in the market. Reardon becomes so embroiled in his own misfortune that when help is offered to him from friends including Milvain – a friendly review, a good word regarding an opportunity – he refuses it. This self-sabotage also feels very true to life – the person who is so habituated to rejection that they miss the opportunities that are presented.

When Marian is in line for an inheritance, it seems Milvain’s dilemma is resolved. He can marry the woman he loves, secure in the knowledge that between them they will have enough to live on. She is also pragmatic enough to accept him on those terms. But when the inheritance isn’t going to come through after all, he backtracks, and his honestly gives way to weakness. Rather than break off, he behaves badly, trying to manipulate her so that she breaks off with him.

At the same time he is angry when his sister marries a man who has money, but is her intellectual inferior, believing she deserves better. There is some beautifully subtle dialogue as the characters struggle with these conflicting demands, between one another and within themselves. The irony is, of course, that Milvain does care, and that’s what makes it harder for him to behave with the clarity he outlined in the opening chapter. This is beautifully subtle writing from Gissing.

Amy Reardon also struggles with the demands of art but hers is a subtly different conflict. It is not just about money but about status, identity, her place in society. She loves fine things, which is an appreciation of beauty, arguably, as much as a love of literature. However, Reardon, in his unhappiness, is unable to find a shared understanding and sees only his own suffering. She feels she can no longer live with him.

After a series of misfortunes, Reardon decides to abandon writing and secures a place as a clerk. He asks her to come back and live with him, as he has secured an income which would be sufficient, if not comfortable. Amy is horrified. She thought she was marrying an up-and-coming writer, she does not want to be the wife of a lowly officer worker, living in a distant suburb, far from the social life she had imagined for them.

This isn’t all about the superficial. She is also concerned about things that we would regard as necessities for her and her child. Gissing is unsparing in this. Amy can’t light a fire when she wants to. She can’t be as clean as she was at home. Even if she wanted to do her own laundry, it’s impossible in a London flat with no outdoor space, and she can’t afford to pay a laundress. Amy doesn’t understand why Reardon can’t be more like his friend Milvain, who is charming and worldly, who makes the right contacts and knows who to charm, who has even set his sisters to work making decent money writing for children.

When Amy inherits a substantial sum of money – unlike her poor cousin Marian, whose inheritance should have come from the same pot – it might have led to a reconciliation, but Reardon is incapable of compromising. He feels her loyalty should have been absolute, and their lack of mutual understanding means they cannot find a way forward.

At the end, after the somewhat convenient death of Reardon, Milvain and Amy marry. It was foreshadowed – by his words in the opening pages of the novel, and by the jealousy that Reardon felt for Amy and Milvain’s similar worldview. (Which writer hasn’t thought – or perhaps been told – Why can’t you be like [insert name here]?) Marian has to eke out a living and care for her sick father, while her cousin Amy gets the inheritance and the man. Amy and Milvain end the book in comfort and mutual understanding. That’s the delicious irony in this ‘happy ending’. Is this because they are pragmatic and without illusions? Or is it just because they are lucky?

I can’t help loving all the writerly gossip, rivalries and jealousy, but New Grub Street takes in much broader issues, about class and money and the price of art. The characterisation is astute. The dialogue scenes, in particular, are beautifully crafted, so you see the struggles of the characters unfold and can sympathise, even when they behave badly.

The writing is beautiful and atmospheric. London is vividly evoked, cloaked in the ever-present fog, with its devastating impact on health and quality of life.

I was particularly interested in the depiction of women’s lives which may be at odds with our image of the time. The young women who feature prominently in the story – Marian Yule, Amy Reardon, and Milvain’s sisters, Maud and Dora, are educated, thoughtful, and articulate. They are viewed as intellectual equals by their male peers. Crucially, the legal framework for women is changing too. The Married Women’s Property Act of 1882 is specifically cited by Amy as meaning the difference between her choosing the life she will live and being forced to return to her life with Reardon.

While Marian ultimately sacrifices herself to support her father, he knows he cannot legally take her money. She has a choice, however constrained. Marian also sports short hair. I’ve tried to find out more about this online but everything I’ve read suggests Victorian women only cut their hair after illness or due to poverty (so they could sell it). However in the book, Marian’s choice is seen as unusual but not unattractive (Milvain is particularly attracted by the nape of her neck).

New Grub Street offers both a fascinating slice of social history and confirmation that, while the technology might have changed, the struggles, schemes and rivalries of the struggling writer are not so different! It’s also made me want to read more of Gissing’s work.

KATEVANE

No comments:

Post a Comment