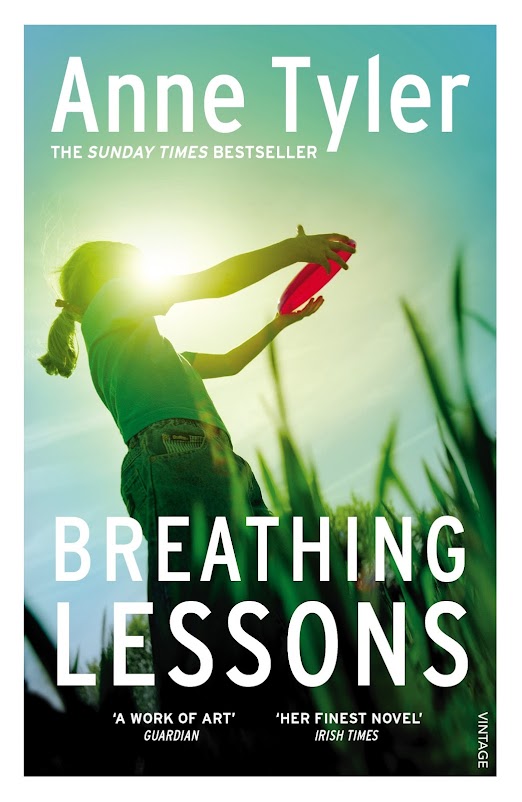

Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler

ABOUT MAGGIE, WHO TRIED TOO HARD

September 11, 1988

BREATHING LESSONS

By Anne Tyler

327 pp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. $18.95.

Anne Tyler, who is blessedly prolific and graced with an effortless-seeming talent at describing whole rafts of intricately individualized people, might be described as a domestic novelist, one of that great line descending from Jane Austin. She is interested not in divorce or infidelity, but in marriage -- not very much in isolation, estrangement, alienation and other fashionable concerns, but in courtship, child raising and filial responsibility. It's a hectic, clamorous focus for a writer to choose during the 1980's, and a mark of her competence that in this fractionated era she can write so well about blood links and family funerals, old friendships or the dogged pull of thwarted love, of blunted love affairs or marital mismatches that neither mend nor end. Her eye is kindly, wise and versatile (an eye that you would want on your jury if you ever had to stand trial), and after going at each new set of characters with authorial eagerness and an exuberant tumble of details, she tends to arrive at a set of conclusions about them that is a sort of golden mean.

Her interest is in families -- drifters do not intrigue her -- and yet it is the crimps and bends in people that appeal to her sympathy. She is touched by their lesions, by the quandaries, dissipated dreams and foundered ambitions that have rendered them pot-bound, because it isn't really the drifters (staples of American fiction since Melville's Ishmael and ''Huckleberry Finn'') who break up a family so often as the homebodies who sink into inaction with a broken axle, seldom saying that they've lost hope, but dragging through the weekly round.

Thus Ms. Tyler loves meddlers, like Eizabeth in 'The Clock Winder'' (1972), Muriel in ''The Accidental Tourist'' (1985) and Maggie Moran in 'Breathing Lessons,' her latest novel. If meddlers aren't enough to make things happen, she will throw in a pregnancy or abrupt bad luck or death in the family, so that the clan must gather and comfort one another. She pushes events on people who don't want anything to happen to them, afraid that if the phone rings they may have to pick up a son at the police station, people accustomed to the idea that if anybody needs to move it usually means he has lost his job. They don't get promotions; they hug what they have. Though once upon a time they did look up the ladder, now they're mainly tryng to keep from sliding into a catastrophe such as bankruptcy, a grown child taking to drink, a bust-up between brothers and sisters who have been smothering or battering each other. Clinging to a low rung of the middle class, they are householders because they have inherited a decayng home, not because they're richer than renters, and they remain bemused or bewildered by the fortuitous quality of most major ''decisions'' in their own or others' lives, particularly by how people come to marry whom they do: a month or two of headlong, blind activity leading to years and years of stasis. And whatever Ms. Tyler puts them through is gong to be uprooting and abraisive before it is redemptive. ''Real life at last! you could say,'' as Maggie tells herself in ''Breathing Lessons.'' (the title refers to the various instructive promptings that accompany contemporary pregnancy.) Maggie, surprised by life, which did not live up to her honeymoon, has become an incorrigible prompter. She doesn't hesitate to reach across from the passenger seat and honk while her husband, Ira, is driving. And she has horned in to bring about the birth of her first grandchild by stopping a 17-year-old girl named Fiona at the door of an abortion clinic and steering her into marrying Maggie's son, Jesse, who is the father and, like Fiona, a dropout from high school. Maggie's motives are always mixed. She wants to get that new baby into her now stiflingly lifeless house and does succeed in installing the young couple in the next room, with the baby and crib being placed in hers. Jesse, in black jeans, aspires to be a rock star to escape the drudging anonymity he sees as his father's fate, in a picture frame store. ''I refuse to believe that I will die unknown,'' he tells Ira (but eight years later as a salesman at Chick's Cycle Shop.) Fiona, after the inevitable blowup, soon moves away to the house of her mother -- the dreadful Mrs. Stuckey -- where Maggie follows to spy on the baby.

Maggie is daring, enterprising and indulges her habit of pouring her heart out to every listening stranger, which naturally infuriates Ira, who, uncommunicative to start with, has reached the point where Maggie can divine his moods only from the pop songs of the 1950's that he whistles. Besides whistling, his pleasure is playing solitaire. He had dreamed of working on the frontiers of medicine, but after he graduated frm high school his father, complaining of a heart problem, dumped the little family business on him, as well as the duty of supporting two unmarriageable, unemployable sisters.

The sisters and the father still live over the shop, and ''for the past several months now,'' as Ms. Tyler confides, ''Ira had been noticing the human race's wastefulness. People were squandering their lives, it seemed to him. They were splurging their energies on petty jealousies or vain ambitions or long-standing, bitter grudges...He was fifty years old and had never accomplished one single act of consequence.'' In reaction, he has become obsessed in his spare time with the efficiency of motors, mechanisms, heaters and appliances, going over and studying them in people's houses where he and Maggie are visiting, or else plunging into one of his solitaire games, which also have at their crux efficiency.

Maggie, by contrast, is working quite happily as an aide at a nursing home, a job she started when high school ended. Her wishful notion that her son would make a good husband and father is based on her memory of him feeding her soup with a spoon once when she was sick. But Ira takes a far more ''realistic,'' severely disappointed view of Jesse, and silently watches Daisy, their daughter -- who at 13 months had undertaken her own toilet training and by first grade was setting her alarm an hour early in order to iron and color-coordinate her outfit for school -- grow away from them and head off for college. As for Maggie, he does still love her, but quotes the brisk witticism of Ann Landers (''Wake up and smell the coffee!'') to her. Ira ought to have married Ann Landers, she thinks jealously. She also has ''Mrs. Perfect'' -- the mother of one of Daisy's school friends at whose house Daisy spends every waking hour -- to worry about. Not long ago Daisy had stared at Maggie for the longest time with this ''fascinated expression on her face, and then said, ''Mom? Was there a certain conscious point in your life when you decided to settle for being ordinary?''

The book's principal event is a 90-mile trip that Maggie and Ira make from Baltimore, where Ms. Tyler's characters almost always live, to a country town in Pennsylvania where a high school classmate has suddenly scheduled an elaborate funeral for her husband, a radio-ad salesman who has died pathetcally soon after discovering that he had a brain tumor. In her grief and confusion, Serena, the widow, expects the service to recapitulate their 1956 wedding, with Kahlil Gibran being read and Maggie and Ira singing ''Love Is a Many Splendored Thing.'' The tumult of memories surrounding the funeral works Maggie into such a state that she gets Ira to lay his cards aside and make love to her in Serena's bedroom during the reception, until Serena catches them and kicks them out.

Ms. Tyler, who was born in 1941, has 10 previous books under her belt, which, as one reads through them, get better and better. Deceptively modest in theme, they have a frequent complement of middle-aged solitaire players, anxious grandparents, blocked bachelors, dysfunctional sisters or brothers, urgent, snappish teen-agers wanting fame the week after tomorrow, unfortunate small children being raised by parents not quite fit for the project, or parents suffering the ultimate tragedy of the death of a child, and they have progressed from her early sentiment in ''Celestial Navigation'' (1974) that ''sad people are the only real ones. They can tell you the truth about things.'' Maggie, although exasperating, isn't sad, and like the more passively benevolent Ezra Tull in ''Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant''' (1982), she is tryng to make a difference, to connect or unite people, beat the drum for forgiveness and compromise. As Ira explains, ''It's Maggie's weakness. She believes it's all right to alter people's lives. She thinks the people she loves are better than they really are, and so then she starts changing things around to suit her point of view of them.''

In the amplitude of her talent, Ms. Tyler didn't hesitate to enjoy her apprenticeship by writing novels on subjects like what might really happen if a bank robber seized you as a hostage in a holdup (''Earthly Possessions''), or the mind of a girl who carves a rock singer's name on her forehead (''A Slipping-Down Life''). One lark of a book (''Searching for Caleb'') starts out like this: ''The fortune teller and her grandfather went to New York City on an Amtrak train, racketing along with their identical, peaky white faces set due north. The grandfather had left hs hearing aid at home on the bureau.'' But the fun of it all didn't prevent her from learning to stick right with her people, complicating their dilemmas, extracting their sorest memories and most tremulous delusions, not hastily moving on when their thought processes dragged or someone's fragile packet of self-esteem was shattered. In every book the reader is immersed in the frustrating alarums of a family -- the Pikes, the Pecks, the Tulls, the Learys -- and though Ms. Tyer's spare, stripped writing style resembles that of the so-called minimalists (most of whom are her contemporaries), she is unlike them because of the depth of her affections and the utter absence from her work of a fashionable concept for life.

She loves love stories, though she often inventories the woe and entropy of lovelessness. She likes a wedding and all the ways weddings can differ, loves to enumerate the idiosyncrasies of children's sensibilities and of house furnishings. Temperate though she is, she celebrates intemperance, zest and an appetite for whatever, just as long as famlies stay together. She wants her characters plausibly married and carring for each other. We're not introduced to ''any Einsteins'' -- as Serena puts it -- in Tyler fiction, nor to the heroic theses typical of many authors in the pantheon of American letters. Her male heroes tend to have trick backs and deliberately give up, settle for decidedly less from life than they had anticipated. It is the amenities of survival that concern her; merciful love, decent behavior in the face of the laming misunderstandings that afflict personal relations. As in ''The Accidental Tourist,'' she writes of worn, sad streets ''Where nothing went right for anyone, where the men had dead-end jobs or none at all and the women were running to fat and the children were turning out badly.'' Nevertheless, she loves the city, with its pearly-tinted sky over such a neighborhood, the whinnying of sound-track horses from the windows of the houses, the women who sweep their stoops even in the middle of a snowstorm and the lilac color of the air while they do so.

Maggie's mother, whose husband installed garage doors for a living but whose father was a lawyer, demands of her, ''How have yu let things get so common?'' And indeed even the tomatoes Maggie grows turn out bulbously misshapen. Her son (''Mr. Moment-by-moment,'' as Ira calls him) is playing his guitar in clubs for no money, just ''the exposure,'' and couldn't even follow through on building a cradle for his baby that he had promised Fiona -- whose ''shrimp-pink'' blouses Maggie regards as low-class, too. After the funeral and the fiasco of her latest plot to bring Jesse and Fiona back together, she recalls another agonizing instance of her meddling -- putting Serena's mother in an old-age home dressed ridiculously as a clown costume because the evening when they were scheduled to arrive there had been Halloween. ''I don't know why I kid myself that I'm going to heaven,'' Maggie tells Ira.

The literature of resignation -- of wisely settling for less than life seemed to offer -- is exemplified by Henry James among American writers. It is a theme more European than New World by tradition, but with the grayng of America into middle age since World War II, it has gradually taken strong root here and become dominant among Ms. Tyler's generation. Macon Leary, the magnificently decent yet ''ordinary'' man in ''The Accidental Tourist,'' follows logic to its zany conclusions, and in doing this justifies the jerry-built or catch-as-catch-can nature of much of life, making us realize that we are probably missing people of mild temperament in our own acquaintance who are heroes, too, if we had Ms. Tyler's eye for recognizing them. ''Breathing Lessons'' seems a slightly thinner mixture. It lacks a Muriel, for one thing. Muriel, the man-chaser and man-saver of ''The Accidental Tourist,'' ranks among the more endearing characters of postwar literature. But Maggie Moran's fatih that crazy spells do not mean life itself is crazy is an affirmation.

Because Ms. Tyler is at the top of her powers, it's fair to wonder whether she has developed the kind of radiant, doubling dimension to her books that may enable them to outlast the season of their publication. Is she unblinking, for example? No, she is not unblinking. Her books contain scarcely a hint of the absence of racial friction that eat at the very neighborhoods she is devoting her woorking life to picturing. Her people are eerily virtuous, Quakerishly tolerant of all strangers, all races. And she touches upon sex so lightly, compared wth her graphic realism of other matters, that her total portrait of motivation is tilted out of balance.

Deservedly successful, she has marked her progress by changing her imprimatur on the copyright pages of her novels from ''Anne Modaressi'' to ''Anne Tyler Modaressi'' to ''Anne Tyler Modaressi et al,'' to ''ATM Inc.'' That would be fine, except that it strikes me that she has taken to prettifying the final pages of her novels, too. And in ''Breathing Lessons,'' the comedies of Fiona's baby's delivery in the hospital and of Maggie's horrendously inept driving have been caricatured to unfunny slapstick, as if in an effort to corral extra readers. I don't believe Ms. Tyler should think she needs to tinker with her popularity. It is based on the fact that she is very good at writing about old people, very good on young children, very good on teen-agers, very good on breadwinners and also stay-at-hmes; that she is superb at picturing men and portraying women.

THE NEW YORK TIMES

No comments:

Post a Comment