A Devil, a Guinness Brewer, and a King: In Praise of 'At Swim-Two-Birds'

This St. Patrick's Day, get acquainted with Irish author Flann O'Brien's funny, bizarre 1939 book of stories within stories within stories.

In 1939, German planes bombed London, damaging, among other buildings, a publishing house that had just released Flann O'Brien's At Swim-Two-Birds. O'Brien blamed the commercial failure of his novel on that raid, which prevented the book's wide release. He may have been right, though he was probably overstating the case when he claimed that Hitler had started the war to prevent At Swim-Two-Birds from reaching the mass audience.

On the other hand ... Hitler was not known for a sense of humor, and At Swim-Two-Birds, which was finally republished in 1960, is perhaps the most subversive and ridiculously funny books in the English language. I can't think of a better way to celebrate the Irish for St. Patrick's Day than by revisiting it.

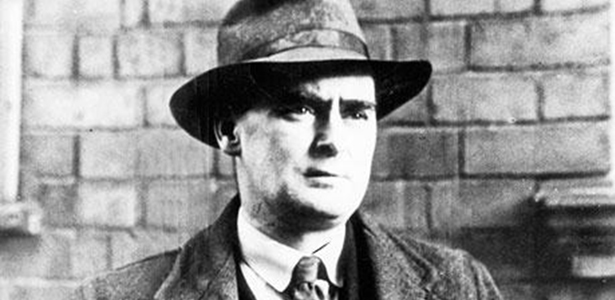

Flann O'Brien was born Brian O'Nolan or, in the Gaelic O'Brien preferred, Brian Ua Nuallain. His nom de plume at the student paper for University College in Dublin was Brother Barnabas, and he was later known, when writing a newspaper column in Gaelic, as Myles na gCopaleen (which translates into, Myles of the Little Horses or, as O'Brien insisted, "Myles of the Ponies" because "the autonomy of the pony must not be subjected to the imperialism of the horse") He was born in County Tyrone in either 1911 or 1912 and died at age 54 from complications due to alcoholism in Dublin in 1966—on surely the day he would have chosen, April 1.

Hugh Kenner is thought to have once asked rhetorically about O'Brien, "Was it the drink was his ruin, for ruin is the word. So much promise has seldom accomplished so little." At the end, "a great future lay behind him."

Perhaps, but taken in whole, O'Brien's novels and newspaper columns, whether written in Gaelic or English—all now in print thanks to the Dalkey Archive—have given him a cult status unmatched by any other Irish writer. Among his legion of fans are James Joyce (who O'Brien often parodied), Samuel Beckett, Graham Greene (who first recommended At Swim-Two-Birds to its British publisher), John Updike, Seamus Heaney (who called At Swim "hilarious and melancholy"), and Roy Blount, Jr. And, oh yes, Dylan Thomas, whose praise for At Swim-Two-Birds is perhaps the most fitting: "Just the book to give to your sister, if she is a dirty, boozey girl."

Only a fool would attempt to describe the plot of At Swim-Two-Birds. Here I go: The title is a literal translation from the Gaelic of ... well, never mind, you wouldn't make sense of it anyway (I certainly couldn't), but it's a ford on the River Shannon said to be visited by the legendary king, Mad Sweeney, who was exiled from his homeland after the Battle of Moira in 637 (see Seamus Heaney's magnificent 1983 translation, Sweeny Astray) and resurrected by O'Brien as a character in his novel.

Still with me? A narrator, a student of Irish literature unnamed by O'Brien, lives with his uncle and has a dream job for an Irishman: He works in a Guinness brewery. He establishes his creed as a writer at the outset: "One beginning and one ending for a book was a thing I did not agree with."

The narrator is a lazy sod who can't seem to finish his book, control his characters, or tie all the strands of his book together. One of those plot streams involves Dermot Trellis, a writer of pulp westerns. Trellis's characters rebel against their creator; wanting control over their own lives, they drug him to make him sleep so much he can't write his book. But Trellis fights off slumber long enough to bring a female character, Sheila Lamont, into existence; she becomes real, or at least real enough to bear his child ("blinded by her beauty"—i.e. of his own fictional creation—Trellis loses control and assaults her).

In time, Orlick is born, inheriting his father's—and presumably the unnamed narrator's and Flann O'Brien's—gift for writing fiction. Orlick writes a novel in which all of Trellis's creations put Trellis on trial and punish him for daring to manipulate him. But, as he is about to be executed, Trellis's creator, the student, unexpectedly passes his exams with flying colors and ...

I don't want to spoil it for you. Actually, I'm not sure that I have all this down correctly, though I've read three separate copies, annotating them all. I'm also still not sure exactly how the two American cowboys appear or why the mythical Irish hero Finn McCool jumps in (or whether he is Sheila Lamont's father) or what part the Pooka (a species of human Irish devil endowed with magical powers) named Fergus MacPhellimey plays. (But I can testify that an invisible good fairy who lives in MacPhellimey's pocket appears at opportune times to counter the Pooka's evil.) Part of the problem is keeping track of the three major intertwined plot threads; an even larger problem is recovering one's concentration after laughing out loud at nearly every page.

Thankfully, you don't have to get all the jokes in order to laugh at them. As V.S. Pritchett wrote, "In O'Brien, the object is a box that contains a box containing boxes getting infinitely smaller, until they are invisible." He might have added that each box contains a joke funnier than the last, though the punch lines are sometimes in Gaelic.

Allen Barra writes about sports for the Wall Street Journal and TheAtlantic.com. His next book is Mickey and Willie--The Parallel Lives of Baseball's Golden Age.

No comments:

Post a Comment