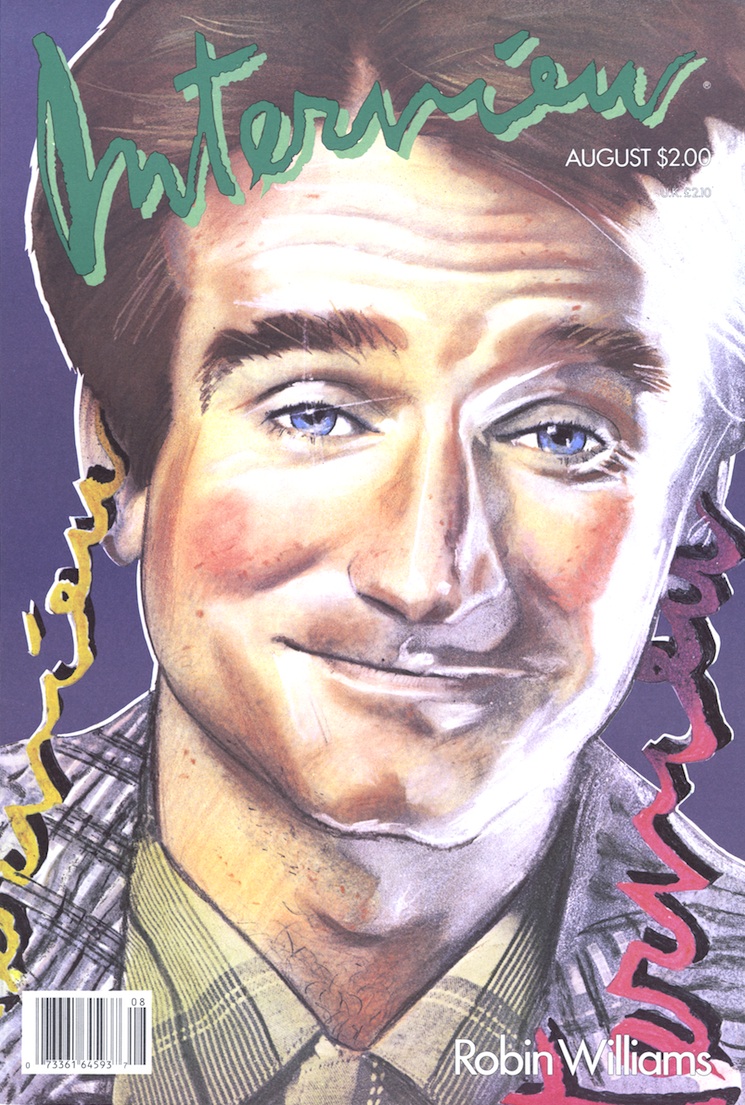

In Memoriam: Robin Williams

When asked what the perfect Robin Williams movie would be in his August 1986 cover interview, the actor told Interview, “Something with spirit, with a character who doesn’t drive people crazy.” At the time, Williams had only a few film credits under his belt. Nearly two decades later, it’s safe to say that he had more than a few perfect Robin Williams movies. Whether through his hilarious portrayal of a housekeeper in Mrs. Doubtfire, his role as the unorthodox John Keating in Dead Poets Society, or his voiceover of a manic genie in Aladdin, Williams truly came to life on the big screen, depicting memorable characters who, despite their madness, were always lovable and inspiring.

Yesterday, news of Robin Williams’ passing shook the world. At 63 years old, Williams had become a legend in Hollywood. Refreshingly bold, original, and talented, Williams had consistently provided us with laughter and iconic performances ever since arriving as an alien back in the days of Mork and Mindy.

In memory of the legendary actor, father, and friend, we take a look back at a candid interview of Williams by Nancy Collins from August 1986. Opening up completely about his life and his struggles in Hollywood, the then 35-year-old actor defended his title as the king of comedy and discussed his love of performing and his family. It’s powerful and regrettably poignant. —Sohyun Choo

Robin Williams

By Nancy Collins

He is arguably the funniest man in America—certainly he is one of the most original. From the moment Robin Williams—playing an adorable space creature named Mork—stole the hearts of TV-bound earthlings, he established himself as a baby-boom comic force to be reckoned with. His sold-out concerts are exercises in stream-of-consciousness comedy. Still, his movies (The World According to Garp, Moscow on the Hudson, and The Best of Times), while funny, have yet to capture the ultimate Williams performance, that distinct character one recognizes instantly when he performs live.

Williams, born in Detroit, migrated with his family to California’s Marin County at the age of twelve. After a dose of the Los Angeles high life, Williams and his wife of eight years, Valeria, a former dancer, moved back up north, where they divide their time between a ranch in the Napa Valley and an apartment in San Francisco.

Last month, Williams returned to the screen with Club Paradise, a Warner Brothers release. In New York on concert tour, the actor is a smaller, more compact version of his screen persona. During several hours of conversation, he is at once thoughtful and hilarious, his Silly-Putty face endlessly mugging, his voice jumping in and out of a hundred characters. He is sweet, somewhat naïve, eager to please—Mork in a Hawaiian shirt.

NANCY COLLINS: How close do you think comedy is to craziness?

ROBIN WILLIAMS: Sometimes there’s no boundary at all. Sometime’s it’s legalized insanity.

COLLINS: Have you jumped over the line a few times?

WILLIAMS: No. Well, maybe once or twice. I try to keep a little distance.

COLLINS: How do you do that?

WILLIAMS: I stopped drinking… That helped a lot, and my son, Zach, keeps me grounded a bit. He has that look in his eyes like, “Oh, father, must you do that?” Like Sylvester in the cartoons. He sometimes says, “Don’t be funny. Don’t say that. Don’t say ‘fuck it.'” We have those rules.

COLLINS: Were you in the delivery room when he was born?

WILLIAMS: Oh, yeah, “sharing the childbirth.” Bullshit. You’re not doing anything unless you’re there circumcising yourself with a chainsaw. My wife, Valerie, had to have a Caesarean because Zach was wrapped up in the cord. Fun. They said, “You have Will Rogers inside there.” Then they put up the little tent and gave her an epidural. So she was awake, asking me about the movie we had watched just before. “Well, how did it end?” “Don’t worry, you’re having a kid.” “What happened? Louis XIV—did he walk through the door?” “Yes, he did. Look! There’s a baby!”

COLLINS: Did you go through Lamaze training?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but what good did it do? It was like going through flight training and ending up in a glider.

COLLINS: Did they give the baby to you right away?

WILLIAMS: First they held him up. You could see him going, “What?! Whaaat? Why these lights? Some mood, some music.” Then he pissed on the doctors and they said, “Yeah, it’s a boy.”

COLLINS: Did it make any difference to you whether you had a boy or girl?

WILLIAMS: Well, first of all, you’re looking at a little creature who imitates everything you do. That kind of cleans you up in one way. Everything that you do, they pick up on, and you realize how precious time is. I’ve been on the road now for a month. I’ll come back and he’ll be a totally different creature.

COLLINS: Is Zach funny?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, very. Very dry. It’s like living with Oscar Wilde.

COLLINS: Is he like you?

WILLIAMS: A little bit. He has this look about him… He performs. He works a room incredibly, the ladies especially. He’s very driven and loves to move and to dance. One time I took him to the Improvisation in L.A., and there was music on. The floor was empty and he just started dancing. One day when he was here in New York he started break-dancing. He saw these kids, walked up and started dancing. The crowd went crazy. “Oh, isn’t that sad? Since he lost the TV show, he’s got the kid working.”

COLLINS: You were an only child, weren’t you?

WILLIAMS: Yeah. It had wonderful advantages, but it’s real lonely. You try to create a family, make brothers out of friends.

COLLINS: What’s your father like?

WILLIAMS: A very elegant man with a powerful voice: He looks like a retired English army colonel, except he’s not. My mother is the one who has the show-business tendencies, but she never exerted them.

COLLINS: Are your parents still alive?

WILLIAMS: Oh, very much so. Or at least they were this morning.

COLLINS: Your childhood sounds almost ridiculously uncomplicated.

WILLIAMS: Very—it’s the contradiction of what people say about comedy and pain. My childhood was really nice. My parents never forced me to do anything; it was always, “If you want to do that, fine.” When I told my father I was going to be an actor, he said, “Fine, but study welding just in case.”

COLLINS: I think an only child has a greater imagination, because clearly you live inside your head more than a lot of kids.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but I didn’t really start doing comedy until college. I was a very quiet kid.

COLLINS: How old were you when you discovered girls?

WILLIAMS: Oh, God, it was great. College—that’s when I first moved away from home. “Let’s make love in a car! I’ve got to have a bed with a stick shift right here.” I had one or two steady girlfriends in high school, but then in college, it was three, four… I went crazy. At one point I had three separate girlfriends, running around mad. That was the second year of college.

COLLINS: Do you remember your first physical relationship?

WILLIAMS: Oh, yeah. It was in college. She was just wonderful, because she was like a deer. I felt like… California love. I just remember this tan creature wandering through brown California.

COLLINS: So you like women?

WILLIAMS: They’re wonderful—they’re amazing creatures. You can never learn enough! They’re addicting in the most amazing sense. They have so many levels. There’s the physical level, which is a lot of fun. There’s this emotional level, which is extremely mercurial. Every 28 days you have that massive mood swing, where nature’s going, “Check, please.” It turns your body into an Etch-a-Sketch, and then you start over. Men may have wars, but women have their period. Men go off and kill each other, but women say nasty things, which is even better. Women are incredibly intuitive. If anybody on the planet is going to evolve to the next level, that telekinetic thing, women will.

COLLINS: Are you able to be around people without performing?

WILLIAMS: Sometimes. Occasionally people say, “Why can’t you just be you?” But this is part of being me, too, the performing. Then there are times when life’s just real quiet and simple. I sometimes get tired of people saying, “Well, what are you really like?”

COLLINS: You first tried stand-up comedy at a place called the Intersection, in San Francisco. Did people immediately say, “Robin, you’re so funny”?

WILLIAMS: No, they just said I was good… interesting. The place where I started was a coffeehouse. They used to have radical lesbian-feminist poetry readings and then comedy after that, so we had an interesting audience to begin with. It was in the basement of a Presbyterian church. It was such a rush the first time I did it! The fun thing was being out there on stage in the total silence. The performance was yours. It you died, it was yours too.

COLLINS: You met Valerie in San Francisco at that time. Was it love at first sight?

WILLIAMS: More like lust. She was this Italian woman, a Napoletana girl. She wasn’t dressed especially sexily; she just looked… hot. Caliente. We hung out for a while, then I started seeing her and, finally, we started living together.

COLLINS: About a month afterward, right?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, and then a year later we were living in L.A., and in another year and a half we were married… and living in L.A.

COLLINS: You’ve been married how long now?

WILLIAMS: Eight years.

COLLINS: What keeps Valerie interesting to you?

WILLIAMS: The account. [laughs] But even after years, you still find out, you grow, you break through to other levels, too, if you allow it to happen. As you get a little older, you mellow and think, “Oh, I see. Now I understand why we’re hanging out.” For instance, I never thought gardening would be fun—sitting around going, “Oh, look. A bud. Honey! Sin semilla!”

COLLINS: What do you think Valerie has done for your career?

WILLIAMS: She’s tried to support me as much as possible. She finds the public aspect very hard, though.

COLLINS: In the beginning, Valerie helped you catalogue your jokes, didn’t she?

WILLIAMS: Oh, yeah. She did a lot of that stuff. We were working hard together, and then this thing took off.

COLLINS: And you’ve stuck together through it all?

WILLIAMS: Yes. It’s been hard. It’s a type of life that tends to tear people asunder. You start to take it seriously. It’s a scary thing, because as hot as this business can be, it can also be just as cold. Having been through both phases…

COLLINS: Cold in terms of—

WILLIAMS: People becoming indifferent. It’s a double-edged thing. Now things are at a nice level; it seems to be quiet.

COLLINS: You two must really love each other.

WILLIAMS: I think there’s something there.

COLLINS: I know that Valerie’s a very private person. It’s interesting that she would fall in love with a man who was looking for public recognition.

WILLIAMS: I wasn’t looking to be recognized—I wanted to have a good time performing. That hasn’t changed. The fame came, and that was strange to me.

COLLINS: In retrospect, now that you’ve been away from Mork and Mindy for a while, what do you think of the show?

WILLIAMS: I think it was incredible. It was outrageous. The first year was really fun and exciting, the second year was aanhh, the third year was really bad and the fourth year was great because Jonathan [Winters] showed up. But you know what television is like—it just sucks up everything.

COLLINS: Around what year did Mork and Mindy stop being fun?

WILLIAMS: The third year was rough, because that year the networks were all trying to bust each other’s balls. That was the year that television was accused of being heavily into tits and ass. Then they started to play with the format and get greedy. They started busting up the basic lineup and the simplicity of the show. It was downhill from there.

COLLINS: Do you think you stayed at the party too long?

WILLIAMS: Mork and Mindy? I had no choice—I was under contract.

COLLINS: Let’s talk about your movie career. Your films have all been individually interesting, but it seems you haven’t quite found a vehicle for your talent yet.

WILLIAMS: Not yet, no. I’ve been trying, but it’s a hard thing. Eddie [Murphy] is ideal—he knows exactly what he does and how to get it out on film perfectly. I don’t—I keep trying different things.

COLLINS: Have you done that purposefully?

WILLIAMS: At one time I did, but now I’m realizing, “Jesus, you’d better find something that you do—real quick.”

COLLINS: Who advises you?

WILLIAMS: I have managers—there are four of them—and then there’s one agent, Sam, if you can get him. “He’s on the coast.” “Well, I’m on the coast.” “Well, he’s on the other coast. He’s in between coasts. He’s in the Midwest. It’s like the coast. No, it’s a lake.” “He’s on a lake? Where?” “No, he’s up North. He’s out.” “Who’s on?” “Sam’s on first. No, you’re on second.”

COLLINS: Which one of your movies did everyone advise against that you went ahead and did anyway?

WILLIAMS: The Best of Times, the one about football. Everybody said it was predictable, and I said, “Yeah, but I still love it.” And it is a sweet film. Some critics said it was wonderful and others said, “Oh, what horseshit.” Sometimes you make a decision just because you love something.”

COLLINS: What do you think the perfect Robin Williams movie would be?

WILLIAMS: God. It’s out there somewhere. It’s got to be. Something with spirit, with a character who doesn’t drive people crazy. Mork was like that—Mork had total freedom, and yet people still found him sweet enough that they could tolerate the madness. It’s a fine line. There has to be a story that’s simple enough and strong enough to keep people going.

COLLINS: When you look at somebody like Eddie Murphy, isn’t there just the teensiest bit of jealousy?

WILLIAMS: No, I’m very happy. I’m only jealous of his sense of knowing so strongly what he wants to do. I’m pretty vulnerable to people saying, “Gee, that sounds great.” Eddie knows exactly what he wants to do—he’ll turn down project after project after project, waiting until he’s sure. I also admire Bill [Murray] because he’s basically a straight-ahead cat who knows exactly what’s coming. He started slowly and just worked his way through.

COLLINS: A lot of actors aren’t as generous as you are.

WILLIAMS: What’s to envy? Things are nice for me. What am I going to say? “God, I need more money than this”? Bullshit.

COLLINS: Do you have a lot of money?

WILLIAMS: Things are nice. All I need is books and more computer games. I don’t want any more land.

COLLINS: What do you think of Hollywood?

WILLIAMS: It’s very strange. It’s the type of place where people don’t eat their young—they put them on hold. I have wonderful friends there—people whom I’ve known for a long time—but I’ve also known people who have done some really nasty things.

COLLINS: When did Hollywood start to fade for you?

WILLIAMS: When the invitations started to cool off, when some of the movies didn’t do well, or were critically nice but didn’t make any money. Things started to get a little quieter, which was fine by me. It took the pressure off.

COLLINS: Did the industry affect your relationship with Valerie?

WILLIAMS: It strained it horribly. She tried to force herself to keep pace with a style of life that she didn’t like. The undercurrent of nastiness was too much for her; she found it massively hypocritical.

COLLINS: What do you think was your most difficult time in L.A.?

WILLIAMS: The third year of the series, and up to a year or two after it ended. Things were cooling down, and I was still trying to push myself and live in that place.

COLLINS: You’ve been pretty candid about your excesses. When did you quit drinking?

WILLIAMS: I quit everything.

COLLINS: Everything? No drugs?

WILLIAMS: Everything. You have to. To begin with, a kid forces you to do that. Like I said, there’s the imitation factor, and besides, you don’t need drugs when you have a kid. You’re awake and paranoid anyway. Who needs anything else?

COLLINS: Were you doing drugs before you went to L.A.?

WILLIAMS: Very seldom, because I didn’t have the money. Once you get the coin—

COLLINS: They give it to you for free.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, samples. I heard a great quote: “You have a drug problem?” “No problem. Everybody’s got it.” Everyone will pump you up if you’re ready, because it also gives them some control over you. You’ll tolerate conversations with people you wouldn’t even talk to in the daylight.

COLLINS: Did your drug problem ever reach serious proportions?

WILLIAMS: Who knows? I pulled out.

COLLINS: Were you so addicted you couldn’t do without it? I’m talking about cocaine.

WILLIAMS: No one will ever admit that. Who knows? I stopped all of that shit at once—they all walk hand in hand.

COLLINS: How long has it been?

WILLIAMS: Four years.

COLLINS: Was it hard?

WILLIAMS: No. First, coke went, then drinking, then everything.

COLLINS: Did you think that coke made you funnier?

WILLIAMS: No, I never performed on it. That’d be stupid. I did it once and it was a bad time. It’s the same thing with athletes. They can’t perform when they have cocaine problems. The drug is a nerve deadener; basically, it’s a local anesthetic. It doesn’t give you that one-second delay you need to be quick. I have lots of comedian friends who still think, “Hey, I’m faster. I’m funnier.” No, you’re just faster. You’re not cooking; you just think you are.

COLLINS: A lot of people think Richard Pryor is not as funny without it.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, that’s sad. They’re putting the pressure on him, too. It’s hard, because even he feels sometimes that he’s…

COLLINS: Not as funny… What do you think, in retrospect, is the impact that the whole Belushi affair had on your life? [Robin Williams had visited John Belushi at the Chateau Marmont before he died on the night of March 5, 1982.]

WILLIAMS: He was a powerful personality and a powerful physical being, too. When someone like him takes the cab, it wises your ass up really quick. He used to sometimes sign autographs “Wise up.” John was on the frontier; he was out there pushing it. When that happened, it was like, “Look at you, you little frail motherfucker. You’re small change, Jack.” That was the main thing. That’s all I’ll say. It’s time now that people let it pass, think positively of his memory and stop digging him up. Everyone’s gone on now—Judy’s [Belushi] gone on, everyone’s gone on—but the press and people keep bringing it back.

COLLINS: Didn’t anybody ever say to John, “This is going to kill you, kid”?

WILLIAMS: People did. He had people who were supposed to watch, but he found ways around them. That’s also testimony to the power of his personality. He could say, “Hey, come on, it’s me.”

COLLINS: When Belushi died—that must have been the nadir of your time in L.A.

WILLIAMS: I think that was pretty much the bottom rung. You don’t get much lower than that. It was time to leave this unhappy watering hole—time not to wander down this canyon any longer.

COLLINS: A lot of people outside the business were surprised to learn of your drug use—you had seemed so angelic.

WILLIAMS: I think there was a little bit of a demystification. I couldn’t keep that illusion up, anyway. Now I feel so much simpler. All I’ve come back to is what I was seven or eight years ago, just enjoying performing… People say I even look younger now.

COLLINS: You looked much older the last time I saw you, in Hollywood.

WILLIAMS: It was the drinking most of all—it bloats you up. But you can come back. Your body says, “Okay, I’ll rebuild the cells if you give me time. I’ll put your skin back, I’ll work on you, I’ll deflate you. When you lose the weight and if you start running again, I’ll get rid of as many toxins as I can.” You get a second chance.

COLLINS: Are you ever tempted to go back?

WILLIAMS: I have no desire to go anywhere near drugs. People say, “Aren’t you tempted?” No, because of the ridiculousness of it. I used to say this on stage, “Cocaine a drug that makes you paranoid and impotent—mmmm, boy. That’s a lot of fun.”

COLLINS: Will you ever be in the position to talk about John Belushi?

WILLIAMS: I don’t know. Maybe someday. It was nothing that exciting even then. It’s what they described in the books—I was there [at the Chateau Marmont] for ten minutes and split. There was no great, wild madness. Nothing there.

COLLINS: Did you sense Belushi was as far-gone as he was that night?

WILLIAMS: No. He was basically saying, “I had a couple. I’m out of here. I’m tired.” He didn’t want me there, obviously, because he had no other intentions.

COLLINS: With this girl. [Cathy Evelyn Smith, currently awaiting trial on charges of involuntary manslaughter and administering dangerous drugs.]

WILLIAMS: Whatever. Someone sent me there. No one seems to know who this guy was who was working the Roxy who said, “Go over there. They’re looking for you.” I got over there, and no one wanted to see me. I have a feeling it was some strange set-up, that they wanted to catch a whole bunch of people and it didn’t come through. I don’t know. That’s another thing that no one’s ever gotten into. It’s a whole other bag.

COLLINS: Smith was allegedly an informant for the police, wasn’t she?

WILLIAMS: I don’t know. No one will ever know, I don’t think, because no one will ever open that whole bag. If they do, they’ll get into a whole other thing.

COLLINS: You mean that there was a whole undercover operation?

WILLIAMS: I don’t know.

COLLINS: When you went home, were you awakened by the police knocking at your door?

WILLIAMS: No, not at all. I didn’t know until the next day. I was on set of Mork and Mindy, and someone said, “You know John’s dead?”

COLLINS: Were you surprised when you head that?

WILLIAMS: Just a touch. [laughs] John wasn’t doing anything out of the ordinary. He looked drunk. I’d seen him drunk before; I’d seen him out there. That’s why I just don’t want to talk about it until it’s resolved. To go back to your question—there’s a whole mystique about that night. It’s been portrayed as some incredible, dark evening. I’ve talked about it very openly, and still, people keep going, “But what happened that night at the Chateau Marmont?” Nothing happened. Wanna give me a lie detector test? They keep making it into something else, and it’s not. I don’t know what else they’ll find out.

COLLINS: Do you think that whole thing hurt your career?

WILLIAMS: No. Oh, God. It couldn’t have hurt it any more than it was at that point anyway.

COLLINS: What do you think is the biggest misconception about you?

WILLIAMS: That I’m hung like a bear. I don’t know what people’s conceptions are, other than that I’m funny sometimes, wild and crazy. Beyond that. I don’t know what people know about me. What they don’t know won’t hurt me.

COLLINS: How do you think your mind works?

WILLIAMS: In spurts. It works in compressions and bursts, compressions and bursts. You relax back a little. You’re working, you pull back a second, and then this flood of things will come.

COLLINS: You have a very quick mind.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but sometimes I can be facile. That’s not the same as being creative. Being facile is using what you’ve heard and just reshuffling things. But when you really break through to something, that’s when you get that “Ooooh.”

No comments:

Post a Comment