J.D. Salinger’s Women

by Deanna Schmidt

It’s no secret that J.D. Salinger was attracted to a certain “type” of woman: young, innocent, and sexually inexperienced. Even though these relationships tended to raise eyebrows from disapproving onlookers, Salinger’s intentions were arguably pure. He never wanted to hurt or take advantage of these women; he was, as I see it, simply looking for companionship. Salinger wasn’t the slighted bit interested in having sex with the women he pursued. His desires were, rather, focused on one thing: the innocence of his female companions. Salinger had succumbed to his own disease— the “Catcher In the Rye complex.” His biggest wish was to find a young girl to love, protect, and live out the rest of his life with. Salinger went through a myriad of women in search of his perfect match, struggling to find a woman who could meet his high standards. While Salinger was waiting to discover his young lover, he crafted stories filled with older men who lusted over them— an outlet that allowed him to fulfill some of the desires that he could not realize in his own life. His writing, however, was not enough to quench his thirst, and Salinger continued to search for this illusory innocent throughout his adult life.

Oona O’Neill

On the surface, 16 year-old Oona O’Neill seemed to be everything that the young, 22 year-old Salinger could have asked for. As the daughter of the Nobel Prize winning playwright Eugene O’Neill, the spotlight shone on Oona at an early age. She was constantly surrounded by men who fawned over her, and she quickly learned to use this power to her advantage to cast a spell on some of most brilliant men of her time, o including the budding writer.

Salinger, like many men before him, was immediately attracted to O’Neill’s beauty and innocence. Her pictures graced the pages of newspapers and magazines, and her smile seemed to entice every man that laid eyes on her. O’Neill was the epitome of innocence; she was named debutante of the year when she was seventeen and was often photographed at The Stork Club clutching a glass of milk (because, of course, she was underage). Soon enough the two were in love, though both were clearly looking for different things from one another. For Salinger, it was O’Neill’s innocence and beauty that charmed him, as well as the scars of her damaging past (O’Neill the father was a notorious alcoholic). He was attracted to people who were broken, and Oona was certainly that. With a distant father, who, like Salinger, thought more highly of his characters than his own children, O’Neill grew up without the father-figure she needed and compensated by dating a succession of accomplished men in order to find one who could replace him. For O’Neill, it was Salinger’s writing that drew her in. His rising career made him a promising candidate to fulfill the role that she was looking for in a man.

Their love affair was cut short, however, when Salinger was shipped off to war after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Their relationship continued for a while through letters, but to Salinger’s dismay and utter confusion, the relationship began to fade. While Salinger was still crazy about O’Neill, and continued to write her ten page letters every day, O’Neill was less enthused. She realized that Salinger was not the man she was looking for— that he was, in fact, too much like her father. She opted for someone much older and more famous to replace Salinger: Charlie Chaplin, the most esteemed actor and film director of the time. Chaplin was everything that Salinger wasn’t: outgoing, loud, and swimming in fame and fortune. Eventually O’Neill stopped replying to Salinger’s letters, and once Salinger found out about her marriage to Chaplin he was sent spiraling. Salinger never did fully get over Oona— and just as O’Neill went through a succession of men to replace her father, Salinger went through a succession of women to replace her.

Sylvia Welter

The next woman that attracted Salinger was Sylvia Welter, who was surprisingly the same age as the young Salinger himself— twenty-six. Salinger was introduced to Welter when he was stationed in Germany as a member of the Counter Intelligence Corps— a group whose job was to gather information on the Nazis. Welter was a woman full of secrets: she was both German and French, yet she often chose to hide the fact that she was German whenever it was convenient. She was smart (she earned a doctorate in medicine), pretty, and very mysterious. Salinger and Welter married in October of 1945, barely escaping the punishments of the non-fraternization law by forging Welter’s identification papers to make her appear as though she wasn’t German.

The couple moved back to New York with Salinger’s parents, who weren’t thrilled about this new addition to the family. Welter was “the enemy,” and she wasn’t welcome in the Salinger household. The couple often fought and were generally unhappy together. What made the situation worse was that Welter was rumored to have been a member of the Gestapo, the secret Nazi police who were the very kind of people that Salinger had been looking to capture while he was stationed postwar. Their relationship shattered when Salinger found this out, and Welter woke up one morning to a plane ticket to Germany left on her breakfast plate. The two separated, yet still had “telepathic communications” with one another and visited each other in dreams, according to Salinger. After their eight month affair, during which Salinger did not write, Salinger was finally able to write again. Welter became a distant memory—the first of many women who dared to try to make themselves more important than his work.

Jean Miller

Next came Jean Miller who was only 14 when the 30-year-old Salinger met her in Daytona Beach, Florida. Salinger was immediately enamored by Miller’s youth and spunk. In those few days while the two were on similarly vacationing, the unlikely couple took numerous walks on the pier and along the ocean— talking, talking, and talking. Salinger was interested in everything that Miller had to say, and Miller, as young as she was, never had this much attention devoted to her before. She didn’t let it get to her head, however, even though Salinger seemed to be more interested in her than she was with him.

Salinger adored Miller’s child-like nature. He loved it when she did cartwheels into the ocean and listened to her like she was the most important person in the world. Salinger was falling hard and fast for a girl who was almost completely unattainable. He fantasized about their life together, telling Miller’s mother, “I’m going to marry your daughter,” and even suggesting to Miller that they move in together (a very rash, Holden-like thing to say). He found inspiration in Miller’s innocence and used her as the basis of his character, Esme, in the short story “For Esme- With Love and Squalor,” a tale that depicts an older man who writes letters to a young girl with whom he is obsessed.

Their “honeymoon” eventually came to an end, yet the two kept in touch through letters and corresponded with one another for the next five years, to the dismay of Miller’s mother who threw away many of Salinger’s letters before her daughter could read them. Interestingly, their feelings for each other never faded— partly because that’s all they were: feelings. They had a strange relationship— one that was romantic, but only barely so. There was no physical intimacy between the two, yet the feelings they had for each other were apparent. Miller described the relationship as being “genderless,” saying, “We were friends. We were buddies. Sex did not come into it.” But clearly, there was more to the relationship than meets the eye.

This was Salinger’s ideal situation, or so he thought. He didn’t have to worry about “ruining” Miller by taking away her innocence or his own self-consciousness about sex, a sore subject for Salinger who only had one testicle. Salinger had everything he wanted: a young girl who reciprocated the feelings he had but didn’t want to go any further. Everything was perfect, until one it wasn’t. Miller made the catastrophic mistake that would destroy their relationship.

Miller’s feelings for Salinger grew stronger each day, and once she reached the age of 20, she pushed him to have sex with her while they were together in Montreal. With this Miller’s innocence was lost, and so was Salinger’s interest in her. Their relationship ended the very next day when Salinger put Miller on an early flight home. Miller described Salinger’s expression to be “a look of horror and hurt” when he realized that she was no longer the innocent girl that he had once longed for. Miller, like Welter, had tried to come between Salinger and his work and had lost her innocence in the process. The result was the same for Miller as it was for Welter and the women who would follow: immediate rejection and ejection from Salinger’s life.

Claire Douglas

Thirty-one-year-old Salinger was at a party when he spotted 16-year-old Claire Douglas from across the room. The two had come with separate groups of people and didn’t get a chance to talk that night, but Salinger was enthralled by Douglas and got her address from one of her friends. He sent her a letter (and we know how charming Salinger’s’ letters can be). Immediately the two began a relationship that consisted of letters and phone calls, with the occasional visit every once in a while.

When Douglas would visit Salinger, she would sleep in his bed, but their relationship was purely platonic. When the two weren’t together, Salinger seemed to be distant, which upset Douglas. This was probably because Salinger was still corresponding with Jean Miller at the time. Salinger went quiet for a while, and in that time Douglas married a man named Mocker. The two were happily married until Salinger decided to come back and lure Douglas away from her husband. Douglas soon became Salinger’s second wife in February of 1955, even though on the marriage license there was no evidence of Salinger’s previous marriage to Sylvia Welter. Salinger was determined to have a clean slate. His wedding present to Douglas was his novelette Franny, a story whose main character (modeled after Douglas), struggles to find herself through her religion.

Douglas’s first husband, Mocker, was a devout Christian, and while Douglas was married to him she was interested in Christianity. Salinger, however, practiced Vedanta, and soon Douglas came to love it as well. The two became absorbed in practicing their religion together, spending their afternoons meditating, doing yoga, and reading sacred Vedantic texts. They were happy, they were fulfilled, but they were unaware of the challenges they would soon face.

After training to Washington D.C. to see a yogi, the couple made love in their sleeper car, which resulted in their first child Margaret. Soon, everything began to change. Douglas was no longer the young girl that Salinger had fallen in love with, and he started to drift away from her and focus more on his work. He became engrossed in writing and created a new family, the Glasses, who would soon replace his real one. The couple had their second baby, Matthew, and by this point Salinger was living in a bunker on the side of their property. He barely spoke to his family, who weren’t allowed to enter his bunker so as to not disturb his writing. Claire was left alone and struggled with raising two kids on her own. Eventually this became too much for her, and the couple divorced in September of 1966. Salinger lost yet another woman because of his intense focus on his work and his inability to sustain a relationship with a woman whose maturity and sexuality refused idealization.

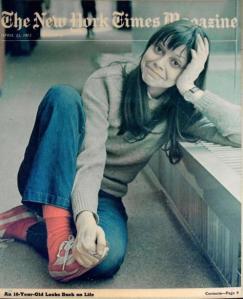

Joyce Maynard

Salinger first discovered Joyce Maynard in “The New York Times” where she had published an article looking back at her life. She was 18 years old, and the 53 year-old Salinger immediately took an interest in protecting her from the detrimental world of celebrity. Their nine-month relationship began when Salinger wrote a letter to the young Maynard warning her of the dangers of the publishing world. The two corresponded, and Maynard described the addictive quality that Salinger’s words had stating, “Getting a letter from J.D. Salinger was like getting a letter from Holden Caulfield, but written just to me— Holden Caulfield telling me how wonderful, perfect, lovable, and brilliant I was. It was a pretty strong drug. It was the only drug I took in college.” Salinger was simply too hard to resist.

Maynard eventually dropped out of college and moved in with Salinger. Their days were spent writing and working on their own separate projects; there was no time for romance. Their relationship was exactly what Salinger wanted: a companionship where work was a higher priority than sex. When the two did engage romantically, Maynard notes that it was predominantly oral sex as opposed to vaginal penetration, which was painful for her. This sexual “compromise” might have been what kept Salinger with Maynard for as long as he was. The couple were not engaging in the “typical” kind of sex, and thus Salinger might have thought of it as being incapable of tarnishing Maynard’s innocence. However, once Maynard expressed an interest in starting a family, their relationship began to crumble. Salinger, who had no interest in having any more children, and perhaps even less interest in having to look at a mature and pregnant Maynard, ended their relationship abruptly while they were on vacation. Their love affair was over, like so many of Salinger’s previous relationships, because of Salinger’ inability to participate fully in a mature relationship.

Colleen O’Neill

After Joyce Maynard, little is known about Salinger’s love life. There were no major relationships (as far as the public knew of) for a long period of time. It was only when Salinger’s house went up in flames that the public heard about Salinger’s newest love: Colleen O’Neill. O’Neill was the one who called in the fire, and with that phone call Salinger’s private relationship suddenly became public. Salinger was 73 at the time, and O’Neill was 40 years younger than him at age 33. Because their relationship was fairly hidden from the public, the exact beginning of their relationship isn’t known, but the two eventually got married, making O’Neill Salinger’s third wife.

Strangely enough, Salinger’s last love had the same last name as his first love: O’Neill. Coincidence? I think not. Salinger spent his whole life looking for a replacement for his beloved Oona O’Neill, and he finally found one in Colleen. Could Salinger’s obsession with replacing Oona have driven him towards a different lover with the same name? I think it’s quite possible. Not only did Colleen have O’Neill’s last name, but she also had her youth. Even though Colleen O’Neill was the oldest woman we know of to have a relationship with Salinger, she also had the largest gap in age with him (40 years compared to Maynard and Salinger’s 35 year divide). There were enough years separating O’Neill and Salinger for him to still consider her “young.”

O’Neill worked as an au pair when she was younger and was dating another man when Salinger offered to give her a ride home one day. She didn’t initially see Salinger in a romantic way and ended up marrying her boyfriend. However, Salinger and O’Neill began corresponding through letters and O’Neill eventually left her husband for Salinger. There isn’t much more information about Salinger and O’Neill’s relationship that is publicly available, but we do know that O’Neill was director of the annual Cornish town fair. She used to walk Salinger around the fairgrounds, repeating things to him when other people struck up a conversation because Salinger was fairly deaf. The two lived out a long and happy relationship that was hidden from the public eye. They kept to themselves, but had friends around town and went out occasionally. As far as the public knows, O’Neill was Salinger’s last love. Was she his greatest? It’s hard to say, but she seemed to make him happy during his last years.

Works Cited:

Shields, David, and Shane Salerno. Salinger. New York City: Story Factory, 2013. Print.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/09/02/15-revelations-from-new-j-d-salinger-biography.html

No comments:

Post a Comment