Bilingual Author Tawada Yōko: Crossing Political and Linguistic Borders

A Writer in Constant Motion

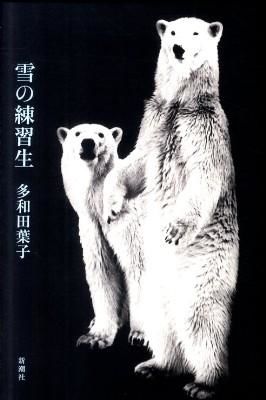

On the day the Nobel Prize in Literature was announced in early October 2019, Tawada Yōko was on a visit to Brazil. Born in Tokyo, Tawada has lived in Germany for decades and is now based in Berlin. Her novels, written in both Japanese and German, have been translated into more than 30 languages. On this occasion, she was in Brazil for an event to mark the publication of the Portuguese translation of Yuki no renshūsei (trans. Memoirs of a Polar Bear/Memórias de um Urso-Polar) a novel about three generations of polar bears that won the Noma Literary Prize when it came out in Japanese in 2011.

Yuki no renshūsei (Memoirs of a Polar Bear), originally published in Japanese in 2011.

European bookmakers listed Tawada among those in the running for the Nobel Prize that year, but she paid no attention to the fuss and remained focused on her hectic promotional schedule. Immediately before coming to Brazil, she had been in the Netherlands to give a lecture about writing in two languages, after which she had returned home briefly for a discussion in Germany with artist Henrike Naumann and filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger. After Brazil, she had a performance lined up with the jazz pianist Takase Aki in Japan. It was a daunting schedule, but for Tawada nothing unusual. For years, she has pursued a creative career in the midst of a constant flurry of movement, giving readings and lectures all over the world.

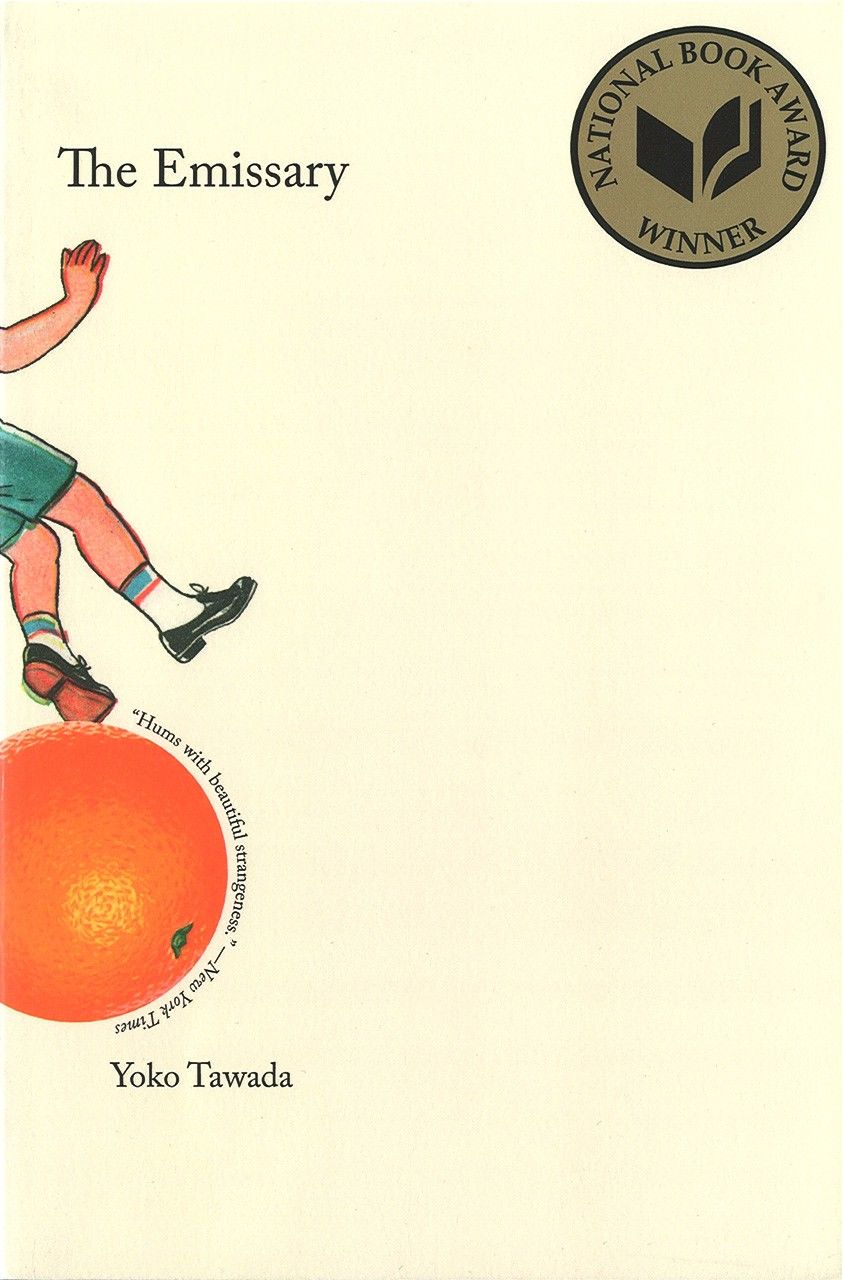

The Emissary, the 2018 translation of Kentōshi.

Since she received Germany’s Kleist Prize in 2016 and an American National Book Award in 2018, Tawada’s name has frequently been mentioned as a contender for a number of important international literary awards. In 2020, her name was again mentioned as a potential Nobel laureate. She has become, quite literally, a writer of international significance. Awarded to an outstanding work written in German, the Kleist prize is one of the most prestigious literary prizes in Germany, whose previous winners include the dramatist Heiner Müller and other well-known names. Tawada was the first Japanese writer to win the prize. The award citation described her work as having opened up new expressive possibilities for writing in German. In the United States, she won a National Book Award for The Emissary, an English translation by Margaret Mitsutani of her 2014 novel Kentōshi, a dystopian story in which Japan has cut itself off from the world in the aftermath of a catastrophic disaster. Tawada’s book was the first to win since the Translated Literature category was revived, and the first Japanese winner since the 1982 prize was split between a book of translations from the Manyōshū poetry anthology and a collection of stories by nineteenth-century writer Higuchi Ichiyō.

Tawada Yōko celebrates winning an American National Book Award for the English translation of her novel Kentōshi (trans. The Emissary) on November 15, 2018. Taken at Waseda University, Tokyo. (© Jiji)

Creativity and New Frontiers in Two Languages

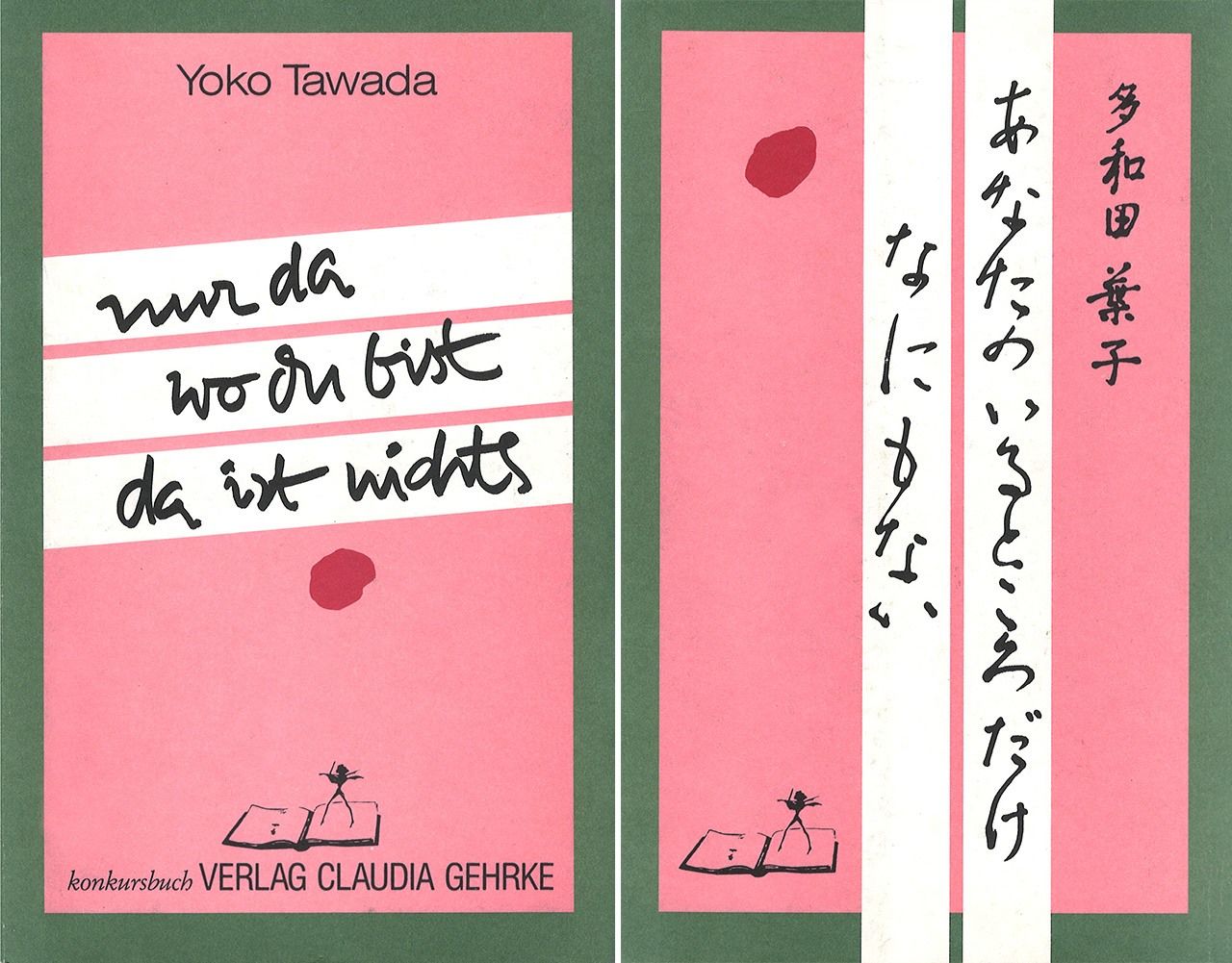

Tawada was born in Tokyo in 1960 and moved to pre-unification Germany in 1982, shortly after graduating from university. She worked for a book distribution company for a while, before publishing her first volume Nur da wo du bist da ist nichts (Nothing Only Where You Are) in 1987 from a publisher in Tübingen.

The book’s unusual binding allowed it to be read in two directions, from both left and right, and featured two covers: one in Japanese, the other in German. It brought together the original versions of poems and stories Tawada had written in Japanese alongside a German translation by Peter Pörtner. This remarkable debut shows an energetic and original author bursting with ideas and relishing the freedom to shake off time-worn idioms, clichés, and the oppressive rules of grammatical convention. The invigorating style of the stories and their fresh way of looking at the world seemed to spring from the author’s life in linguistic exile: living her life surrounded by a foreign language and forced to confront questions about linguistic identity and what it means to speak of a “mother tongue.”

One book, two covers: the German and Japanese title pages of Tawada’s first book, published in 1987, Nur da wo du bist da ist nichts (Nothing Only Where You Are).

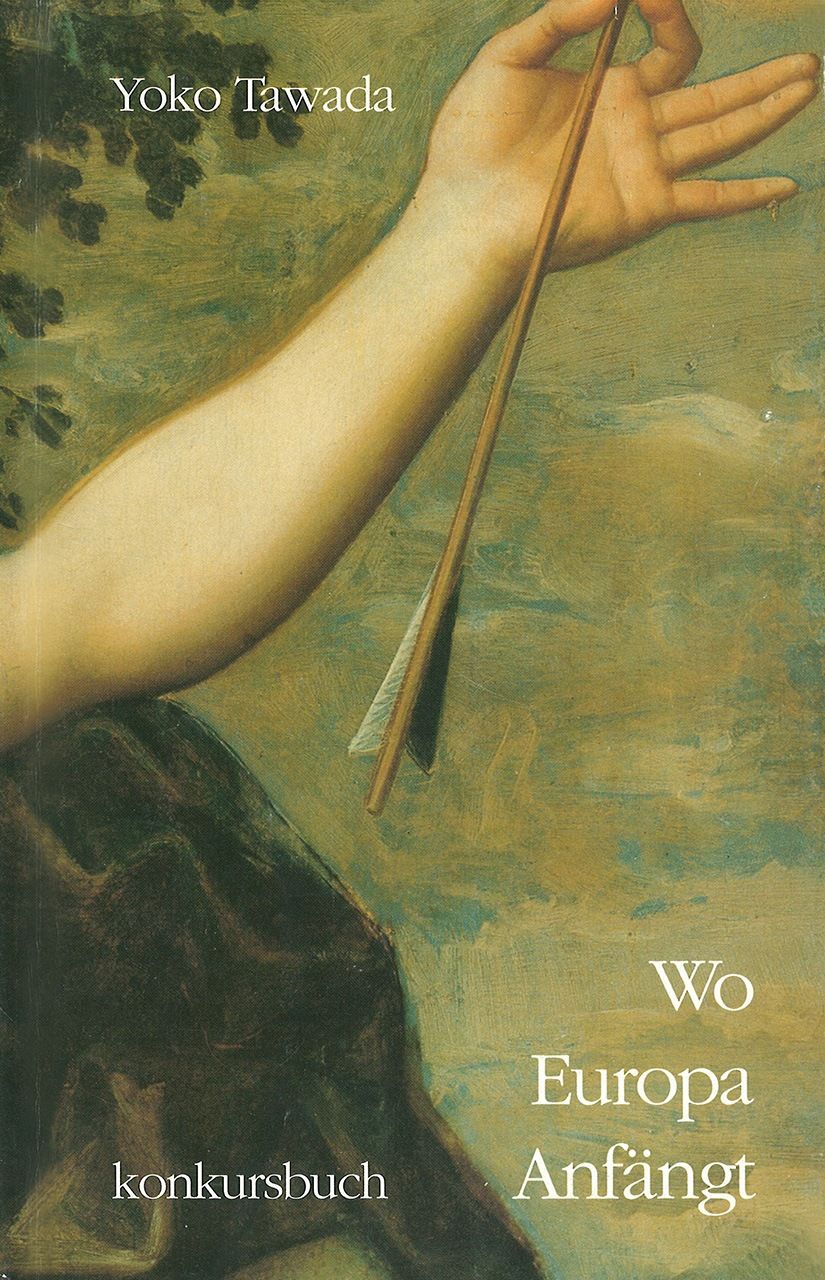

In 1988, she received a literary prize from the city of Hamburg for a story written in German with the title, Wo Europa anfängt (trans. Where Europe Begins), depicting a journey from Japan to Europe on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Her Japanese debut came three years later, in 1991, when she won the Gunzō Award for New Writers for the story “Kakato o nakushite” (Missing Heels). The story depicts the experiences of a Japanese woman as she comes to terms with an unfamiliar culture after moving to a foreign country after marriage. Since then, she has continued to hop between genres and languages, publishing novels, poetry, plays, radio dramas, and essays in Japanese and German. Her backlist now comprises more than 20 volumes each in Germany and Japan.

The 1988 novella Wo Europa anfängt (trans. Where Europe Begins).

Other authors have written in a language other than their mother tongue: Russian-born Vladimir Nabokov, for example, who wrote many of his best-known books in English, or Milan Kundera, who switched from his native Czech to French after fleeing Czechoslovakia for Paris. Many of these border-crossing writers were exiles who left their native countries for political or economic reasons, and eventually took to writing in the language of the country where they had resettled. But Tawada’s decision to write in German was a matter of personal choice. And her German debut came before she had published anything in Japanese. Even since becoming well known in Japan, she has continued to switch back and forth between the two languages, using the linguistic shift to stimulate her creativity. She has now been working as a writer between two languages and cultures for nearly 30 years. Her remarkable career stands as a radical challenge to the very concept of a “national literature.”

People and Cultures Across Borders

The original 2014 edition of Kentōshi (trans. The Emissary).

Throughout her career, Tawada has broken new ground with each book she has published. In recent years, she has embarked on yet another period of transition, publishing the first two volumes of what she says will eventually form a trilogy of novels. The first part Chikyū ni chiribamerarete (Encrusted in the Earth) appeared in 2018, and was followed by Hoshi ni honomekasarete (Written in the Stars) in 2020.

The Emissary is set in a Japan that has cut itself off from the rest of the world following a catastrophe reminiscent of the disaster that took place at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2011. In her latest series, an unnamed island nation that bears a close resemblance to Japan has apparently vanished entirely. The reasons are never made clear, but there are dark hints—in the stories of the terrible pollution that caused symptoms similar to those of Minamata disease, and of protests against nuclear power—that the country’s destruction came about as the result of a human-induced disaster.

The 2018 novel Chikyū ni chiribamerarete (Encrusted in the Earth).

The main character of the trilogy is an immigrant from this vanished archipelago called Hiruko, her name always written in alphabetic script, making it stand out starkly from the surrounding Japanese text and emphasizing her status as a strange, alien presence. The name comes from the “leech child” who occurs in the Japanese creation myths, the misconceived firstborn of the creator gods, who abandon the child to the waves. As the name suggests, Hiruko has become cut off from her native land and wanders from place to place in Scandinavia. The novels reflect the times we live in, when the contentious issues surrounding immigration have become the focus of attention and debate around the world. The trilogy also addresses other issues, including natural disasters, language, ethnicity, gender, and identity. As the world reels from the ongoing pandemic that has closed borders and placed limits on movement around the world, many readers will no doubt find a further reflection of present-day reality in Hiruko’s plight, cast adrift and unable to return home.

While the subjects raised in the novel are among the most serious facing human societies today, the prose sparkles with Tawada’s customary playful use of language, and the novels offer a fresh perspective that frees the shackles of conventional thinking in the reader’s mind. Hiruko speaks a unique jargon made up of a jumbled mix of Scandinavian languages—the skillful and evocative way in which this language is captured in Japanese is one of the pleasures of reading the books.

The 2020 novel Hoshi ni honomekasarete (Written in the Stars).

Isolated from her linguistic community, Hiruko sets off on a quest to find fellow speakers of her “mother tongue,” together with companions who come from a wide variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds. In the first novel, one of the speakers of her “mother tongue” she encounters is a Greenlander who works in a sushi restaurant in Germany—one of several experiences that shake her confidence in what it means to be a “native speaker.” As we accompany Hiruko and her companions on their journey, we begin to adapt to a new way of looking at the world in a globalized era, where peoples and cultures cross borders and become “encrusted” in different places around the globe. The narrative urges us to let go of rigid ideas about the “purity” or “uniqueness” of linguistic and culinary cultures and to adopt a more flexible way of thinking about the world. In the second novel, the story continues on an even larger scale, with the earth presented as just one planet out of many in the universe.

Where will the journey take Hiruko and her companions next? What new horizons lie ahead for Tawada Yōko and her ground-breaking literary journey? One thing seems certain: Tawada Yōko will remain one of the most crucial and visionary voices in global literature.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 15, 2020. Banner photo: Tawada Yōko receives Germany’s Kleist Prize on November 20, 2016)

No comments:

Post a Comment