Kawabata Yasunari: Finding the Harmonies Between Literature and Traditional Art

In November 1947, when the writer Kawabata Yasunari traveled to Kanazawa for the unveiling of a monument to the writer Tokuda Shūsei, he also viewed a six-panel folding screen. Also an art collector, Kawabata owned the national treasures Tōun shinsetsu zu (Snow Sifted Through Frozen Clouds) by Uragami Gyokudō and Jūben jūgi zu (Ten Advantages and Ten Pleasures) by Ike no Taiga and Yosa Buson. Both works, now in the collection of the Kawabata Yasunari Foundation, were designated as national treasures after he bought them, indicating his keen aesthetic eye. Yet, art appreciation was not just a hobby for Kawabata. The screen he saw in Kanazawa stimulated his creativity.

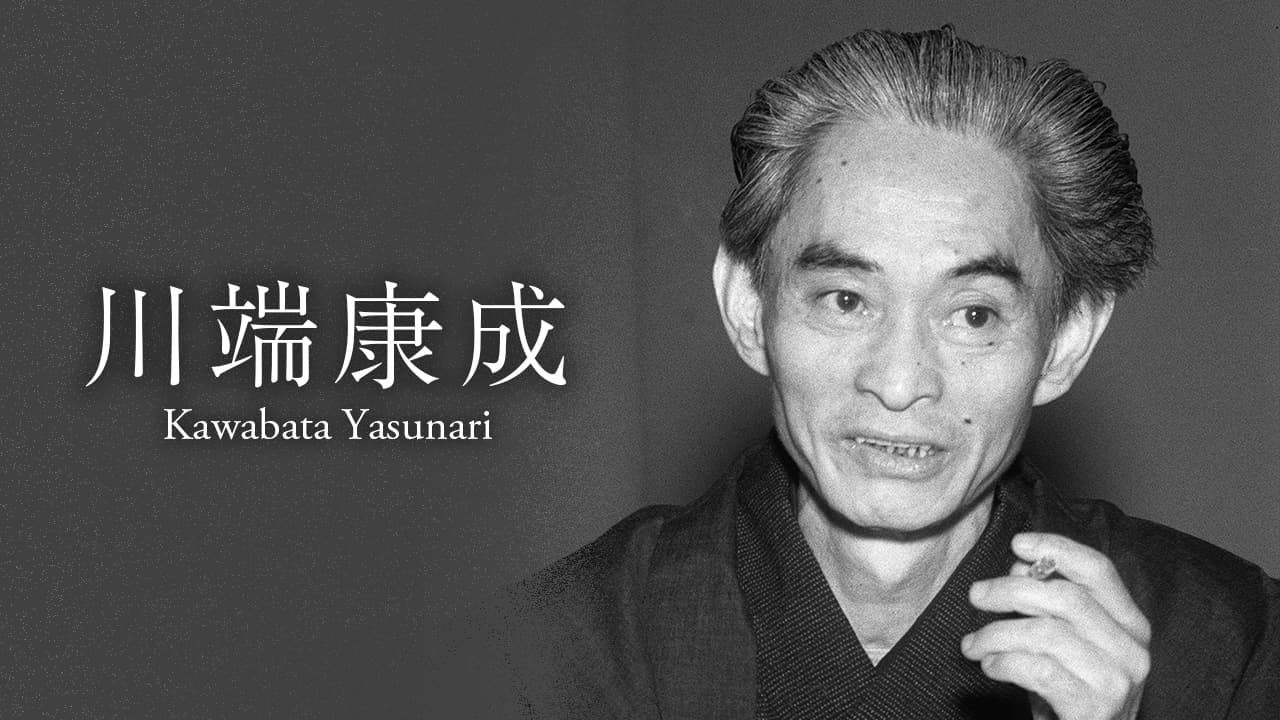

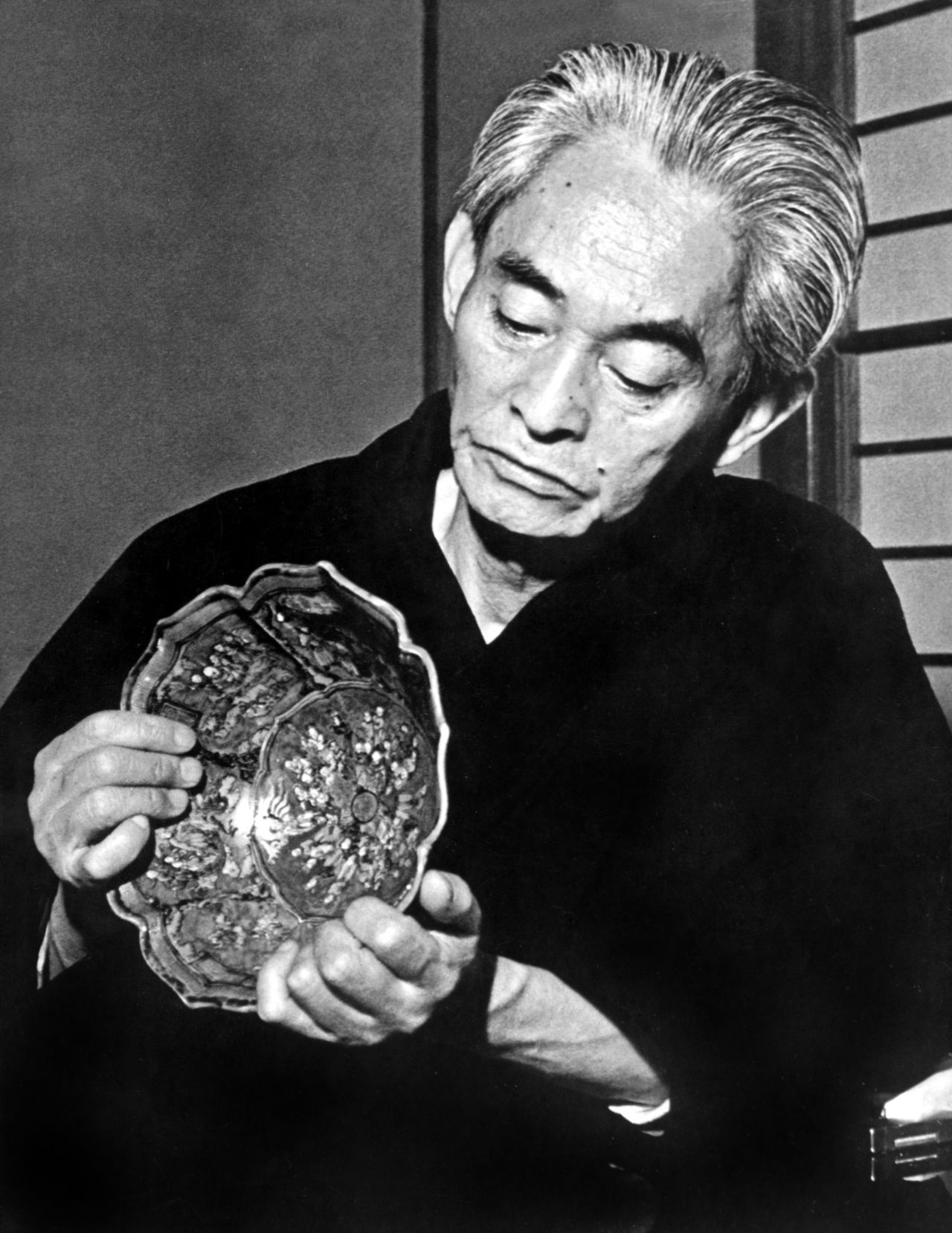

Kawabata Yasunari examining an artwork at his home in Zushi, Kanagawa Prefecture, in April 1972. (© Aflo)

Cinema and Sensuality

When he viewed the folding screen, Kawabata was approaching a new phase in his literary development, the start of which was marked by the completion of his novel Yukiguni (trans. by Edward Seidensticker as Snow Country)—which was later to win international recognition as a masterpiece.

Born in Ibaraki, Osaka Prefecture, in 1899, Kawabata made his name as a new author with the 1926 short story “Izu no odoriko” (trans. “The Dancing Girl of Izu”) about a male student’s encounter with a performing troupe. He further established himself with the 1929–30 work of reportage Asakusa kurenaidan (trans. The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa); the 1931 Suishō gensō (Crystal Fantasies), which employed the latest stream-of-consciousness method; and the 1933 story “Kinjū” (trans. “Of Birds and Beasts”), about a misanthropic man who can only love small birds and animals. After this, he started to write Snow Country.

Shimamura, the Snow Country protagonist, travels from Tokyo by train, emerging from a tunnel into a hot spring town in the “snow country” of the title. There, he is attracted by the geisha Komako’s single-minded self-sacrifice, while remaining persistently distant in manner himself. Kawabata adroitly depicts their fruitless relationship through such expressive techniques as image association, metaphorical hints, and free narration fixed to no particular point of view. Itasaka Gen, who lectured on Japanese literature and culture at Harvard University for many years, noted the innovative way in which Kawabata employed a cinematic method of indirectly expressing both a sultry atmosphere and the distance separating the two through intentional close-up descriptions of Komako’s lips and eyelashes. Kawabata is masterful in his use of literary techniques to create a world of beauty and sensuality, and may be said here to have brought his oeuvre to a point of perfection.

Snow Country came together in an unusual way, as it originally appeared as separate short sections in various magazines from 1935. Even after it was published as Yukiguni in book form in 1937, Kawabata continued to write the story and edit what he had written so far. Following the publication of a continuation in the magazine Shōsetsu Shinchō in 1947, a revised version of the whole described as the “definitive version” was published in 1948. Even so, Kawabata made further changes when it was included in his collected works. After he took his life in 1972, a handwritten manuscript was found with a condensed rendering of the story. It truly was a work he poured heart and soul into until his death.

The Kasumi-no-ma room in the Takahan ryokan in Yuzawa, Niigata Prefecture, where Kawabata Yasunari wrote Snow Country. (© Jiji)

While the creation of Snow Country was a complex process, the 1947 magazine publication brought the work to a temporary closure, and one can imagine that Kawabata had reached a major destination on his literary journey. With the next year’s definitive edition of Snow Country, it was time to make preparations for putting out his collected works. As such, his encounter with the screen in Kanazawa came when he was consolidating his body of work stretching back to the prewar period, and looking for a new direction.

Autumn Inspiration

What kind of screen was it? In a letter to the author Shiga Naoya, he wrote of viewing Ogata Kōrin’s Kikuzu byōbu (Chrysanthemum Screen) in an antique art store in Kanazawa. This was a screen of six panels—one half of a pair—on which chrysanthemums were painted with gofun (a white pigment made from crushed seashells) on a gold background.

Kawabata then began work on another of his most famous works, Yama no oto (trans. The Sound of the Mountain). Like Snow Country, it initially appeared in disparate parts in magazines from 1949 to 1954 before being arranged into one work.

Against the backdrop of a devastated postwar society, The Sound of the Mountain centers on Ogata Shingo, a businessman in his sixties, and deals with issues of aging and family. The title comes from the sound he hears from the mountain behind the Ogata house in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, which he fears is a sign of impending death. In addition to concerns over his health, his children’s ailing relations with their spouses are a further cause of heartache. As he passes gloomy days, Shingo sees the sister-in-law he yearned for as a young man in his son’s wife Kikuko. While his wife’s dead sister is associated with freshly colored autumn leaves, Kikuko recalls the chrysanthemums (kiku) that are part of her name. The beauty of both is heightened in an autumn setting.

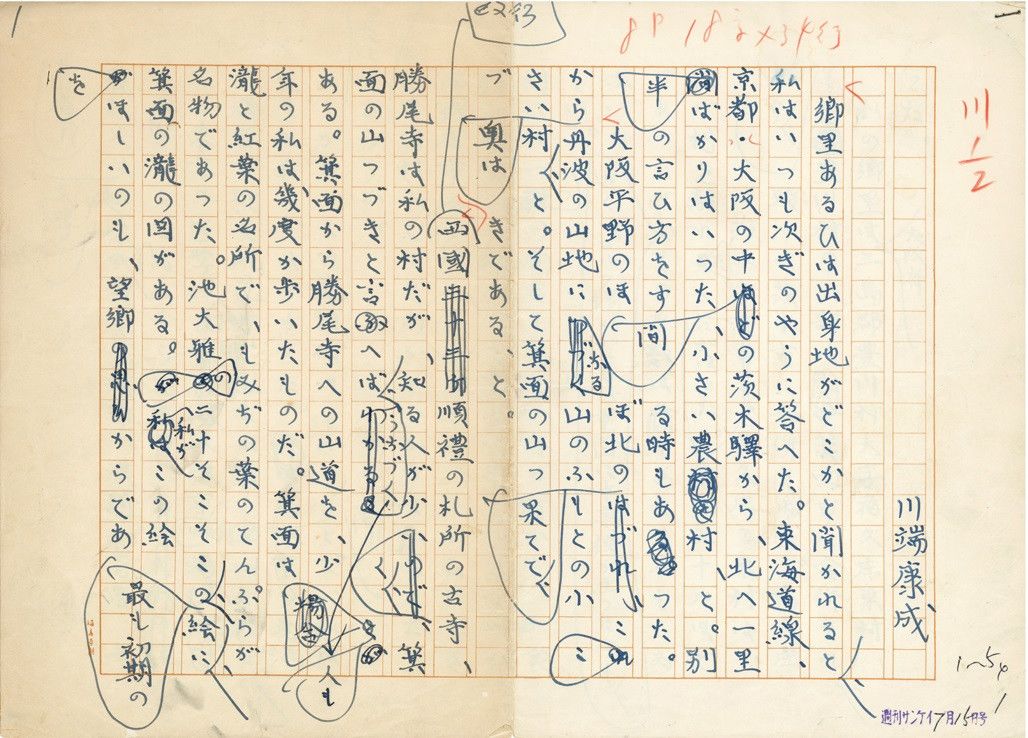

A handwritten manuscript of Kawabata Yasunari’s essay “Watashi no furusato” (My Hometown) discovered in 2017 in Ibaraki, Osaka, where he lived from age 3 to 18. The page shows repeated revisions. (© Jiji)

It seems that when Kawabata was writing about the two women Shingo yearned for in The Sound of the Mountain, the screen may have given him the idea for Kikuko, while he developed the sister-in-law with the traditional combination of chrysanthemums and maple leaves in mind. I am moved to think that there is a code in the work showing that Ogata Kikuko’s name derives from the chrysanthemum screen by Ogata Kōrin. Traditional art thereby inspired the next stage in Kawabata’s literary journey.

After the serialization of The Sound of the Mountain was complete, in 1957 Kawabata visited Westminster Abbey in London. In his 1962 Jiman jūwa (Ten Stories of Self-Pride), he writes that while listening to the choir sing in the abbey, he suddenly recollected the works of Kōrin’s brother Ogata Kenzan. It is possible to discern his interest in the Rinpa school from Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Hon’ami Kōetsu to Ogata Kōrin and Kenzan. Recalling the beauties of Japan in paintings by Kenzan while in a foreign land made him feel homesick.

The specific works mentioned are Teika ei jūnikagetsu waka kachōzu (Fujiwara no Teika’s “Birds and Flowers of the Twelve Months”), based on waka by Teika; Yatsuhashizu (Eight Bridges), from a scene in Ise monogatari (trans. The Tales of Ise); Hanakagozu (Flower Baskets), depicting autumn flower baskets and a waka by the medieval noble and scholar Sanjōnishi Sanetaka; and Shiki kachōzu byōbu (Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons), a pair of folding screens with egrets and seasonal plants. The last is known to have been in Kawabata’s collection; its left screen portrays the autumn maple leaves and white chrysanthemums that correspond to the two women in The Sound of the Mountain. A symphony of Rinpa school works contributes to the creation of the novel.

In Ten Stories of Self-Pride, Kawabata touches on art historian Kobayashi Taichirō’s theory that characters from The Tale of Genji are represented in the flowers and birds in Flower Baskets and Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons. This shows his extraordinary interest in the harmonies between art and literature that can be found in works’ deeper layers.

Later novels by Kawabata included the 1954 Mizuumi (trans. The Lake), about an inveterate middle-aged stalker, and Nemureru bijo (trans. House of the Sleeping Beauties; 1960–61), set in an establishment where old men sleep alongside young, beautiful women who have taken sleeping medicine. Such works trawled the depths of human sexuality and expanded Kawabata’s literary world. In 1968, he was honored as Japan’s first winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 13, 2021. Banner photo: Kawabata Yasunari in 1957. © Jiji.)

NIPPON

No comments:

Post a Comment