|

| Daido Moriyama |

Moriyama Daidō: Photographer with the “Eyes of a Stray Dog”

Moriyama Daidō wanders the streets like a stray dog, taking snapshots that leave vivid impressions on viewers. He is mentioned with the likes of Araki Nobuyoshi as one of Japan’s contemporary master photographers.Exhibits by modern Japanese photographers have become common at art museums and galleries in all parts of the world since the 1990s. Moriyama Daidō stands alongside Araki Nobuyoshi as one of the most popular artists featured in these shows. Recent years have seen a number of large-scale Moriyama exhibitions, including a two-man exhibition with William Klein at the Tate Modern in London in 2012 and a one-man show, “Daidō Tokyo,” at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris.

Many young photographers in Japan, as well as their counterparts elsewhere in Asia, Europe, and other regions of the globe, have been strongly influenced by Moriyama’s black-and-white snapshot style that captures its subjects with, as he himself described it, “the eyes of a stray dog” wandering the streets. He is rightly called one of modern Japan’s major photographers.

Beginnings as a Graphic Designer

Moriyama Daidō was born in 1938 in Ikeda, Osaka Prefecture. His father worked in an insurance company, and his job caused the family to move often when Moriyama was a child—to Shimane, Chiba, Fukui, back to Osaka, and onward to still more of Japan’s prefectures. Moriyama has said that his frequent changes in school never let him get too close to the surrounding communities, and he often spent his afternoons after school wandering around whatever town he was in. The formative experiences of that time may be one of the reasons he later became fixated on street snapshots.

In 1955 Moriyama dropped out of Kōgei High School, a municipal school in Osaka, and began working as a freelance graphic designer. His experiences at that time came to be used in his later photographs—at first glance his snapshots appear to have a rough, unstable composition, but he then crops and prints them with keen attention to every detail, striking a fine balance that utilizes the skills he gained as a designer.

As a young man, however, Moriyama found it difficult to bear sitting at a desk all day designing matchboxes or calendars. As he came into contact with photographers as part of the job, he developed a strong interest in taking his own pictures. In 1960 he became an assistant in the studio of Iwamiya Takeji in Osaka. During his time in the Iwamiya studio, he was strongly affected by William Klein’s 1956 photography collection New York. He also studied street snapshots with Inoue Seiryū, a photographer several years older than him who was known for his documentation of Kamagasaki, an area of Osaka home to many day laborers. The idea of becoming a photographer and working on a larger stage grew in him.

In 1961 Moriyama moved to Tokyo. There he wanted to be involved in some way with the Vivo photographers’ group formed by Tōmatsu Shōmei, Narahara Ikkō, Kawada Kikuji, and others, but it had already disbanded. Moriyama was then picked up by Hosoe Eikō, one of the members of Vivo, to be an assistant. At the time that Hosoe was in the middle of producing the photo collection Barakei (1963), modeled on Mishima Yukio; Moriyama was able to learn a range of shooting and darkroom techniques. By the time he married in 1964, he had become an independent freelance photographer. Of course, he had virtually no work.

“Inu no machi” (“Misawa,” 1971). Taken in Aomori Prefecture, this shot would be a defining moment in the career of the photographer, who came to see his own street-photography gaze as similar to the stray dog’s somewhat furtive, but intensely interested, look. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

“Inu no machi” (“Misawa,” 1971). Taken in Aomori Prefecture, this shot would be a defining moment in the career of the photographer, who came to see his own street-photography gaze as similar to the stray dog’s somewhat furtive, but intensely interested, look. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

Photos as an Indictment of the Times

Moriyama lived in Zushi, Kanagawa. He would often go to the nearby city of Yokosuka, home to an American naval base, taking snapshots of the unique street atmosphere in that area. He took these photos to a magazine called Camera Mainichi. There they captured the attention of legendary editor Yamagishi Shōji, who decided to print them in a nine-page spread entitled “Yokosuka” in the August 1965 issue of the magazine.

This was essentially Moriyama’s debut, and the reaction was huge. Moriyama began publishing photos regularly in Camera Mainichi and Asahi Graph. The Japan Photo Critics Association presented him with its Newcomer’s Award in 1967 for a series of biting works on local Japanese sensibilities, and his first printed collection, Nippon gekijō shashin chō (The Japan Theater: A Photo Book), was published in the following year. That same year he was involved from the second issue in Provoke, a privately published magazine started by Nakahira Takuma, Taki Kōji, Takanashi Yutaka, and others as “provocative fodder for thought.”

Moriyama’s run continued. In 1969 his experimental work, Accident, which mixed copied poster and advertising flyer photos with snapshots taken on the street, was serialized in Asahi Camera. In 1970 he published nudes in Weekly Playboy, alternating each week with Shinoyama Kishin. From a stay in New York with Yokoo Tadanori in 1971, he published a series entitled Nani ka e no tabi (Journey Toward Something) in Asahi Camera. His activity in this period peaked with the 1972 photo collection Shashin yo sayōnara (Goodbye, Photography), a collection of grainy, out-of-focus photos in which it was mostly unclear what was being shown.

Looking at the Interplay of Light and Shadow

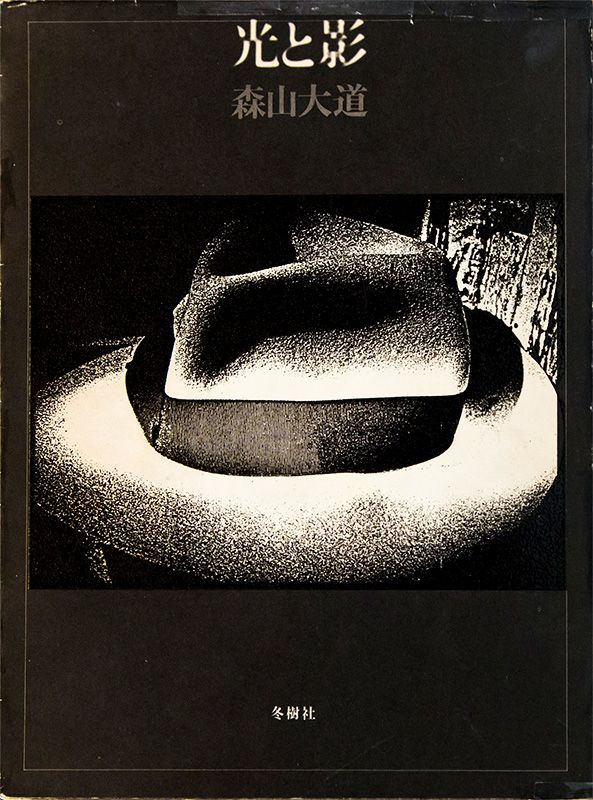

The radical expression of Moriyama and Nakahira, which had an apt backdrop in the age of rising protest against the revision of the Japan-US Security Treaty, began to gradually lose traction with the start of the 1970s and the rapid ebbing of Japan’s “season of politics.” Whatever Moriyama did seemed to elicit no response, and as he struggled to find a foothold he gradually came to feel that he had lost his way. By the end of the 1970s he was closeting himself at home, driven to a place where he could take almost no pictures. Debilitated both physically and mentally, what finally brought him back to the world of photography was the start of a series entitled Hikari to kage (Light and Shadow) in Shashin jidai (Photography Age), a magazine focused mainly on Araki Nobuyoshi that launched in 1982.

“Hikari to kage 1 (hana)” (“Light and Shadow 1: Flower,” 1981). (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

“Hikari to kage 1 (hana)” (“Light and Shadow 1: Flower,” 1981). (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

Moriyama published Light and Shadow as a collection in 1982.

Moriyama published Light and Shadow as a collection in 1982.

The photos in Light and Shadow, published as a photo collection in 1982, were scenes Moriyama came upon with intersecting brightness and darkness, starting with a peony he happened to photograph near his house. He returned to the starting point, taking and printing straightforward shots of primordial views that could be called the basics from the dawn of photography, and regained the confidence to resume his journey as a photographer. Reflecting on this time in his 1984 Memories of a Dog, he wrote, “I stood with my camera in the light, no longer thinking of anything. Below my eyes was my shadow. That was enough. . . . Then I started off toward a time in which I had no intention of ever again being at a standstill.”

In addition to Light and Shadow, the journal Photography Age carried a succession of ambitious and experimental works by Moriyama: Tokyo (1982–84), Nakaji e no tabi (A Journey to Nakaji, 1984–85), Documentary (1985–86) and Utsukushii shashin no tsukurikata (How to Make Beautiful Photos, 1986–88). These works would later be published as standalone photo collections. He spent 1988 and 1989 in Paris, where he dreamed of launching a gallery. This wish would go unrealized, but there were also fruitful outcomes, such as his photos of the ancient Moroccan capital of Marrakesh in Northern Africa.

Radiating Snapshots

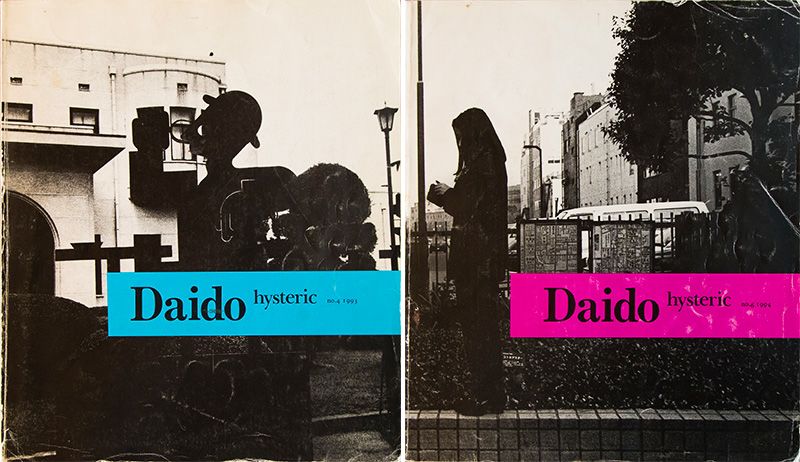

In the 1990s Moriyama’s activities as a photographer accelerated and broadened considerably. From 1993 through 1997, the apparel maker Hysteric Glamour, led by Kitamura Nobuhiko, published three photo collections billed Daido Hysteric. The themes were street objects (1993), city crowds (1994), and scenes of Osaka, Moriyama’s hometown (1997). These large-format books, spanning more than 300 pages each, were infused with Moriyama’s cumulative experience in street snapshots, becoming a series that may be called a culmination of his work to that time.

Two of the Daido Hysteric volumes that came out in the 1990s.

Two of the Daido Hysteric volumes that came out in the 1990s.

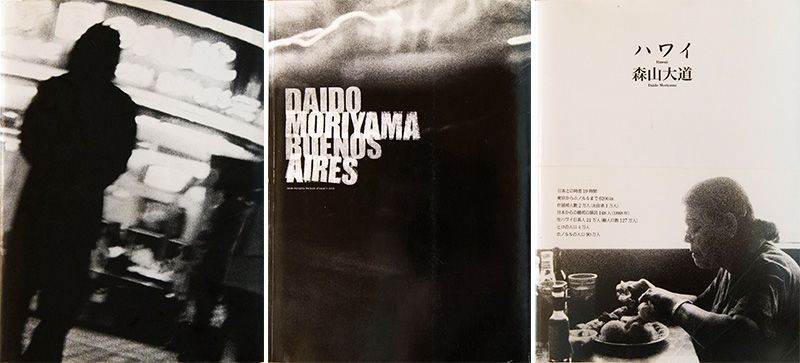

His collection Shinjuku in 2002 was another noteworthy achievement. Shinjuku is an area that Moriyama had been fond of photographing since he moved to Tokyo in 1961—a place where, by placing himself in its crowds and encountering all kinds of people, he felt energized as a photographer. Those “grand outskirts and rough quarters” were brought together in a 600-page collection of 524 photographs. In the 1990s and 2000s he also began spending quite a bit of time overseas, publishing the collections Buenos Aires (2005), Hawaii (2007), and Saõ Paulo (2009). Looking at these collections, one sees that Moriyama is filled with conviction that drives him to take slices of life, in his own style, anywhere in the world.

The Shinjuku, Buenos Aires, and Hawaii collections show an artist increasingly at home around the globe.

The Shinjuku, Buenos Aires, and Hawaii collections show an artist increasingly at home around the globe.

A Stray Dog Wandering an Interconnected World

Moriyama’s creative impulse remains as strong as ever, and his international profile continues to grow even now that he is in his seventies. At his 2016 one-man exhibition, “Daido Tokyo” (Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris), two works in particular had a huge impact on visitors: “Tokyo Color,” a color photo taken with a digital camera, and “Inu to ami taitsu” (Dog and Fishnet Tights), a powerful black and white piece.

The celebrated images from the 2016 “Tokyo Color” show, 2008–2015. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

The celebrated images from the 2016 “Tokyo Color” show, 2008–2015. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

Why is Moriyama’s work so highly regarded? It may be that his collected works, taken over more than a half-century, condense the “street experiences” of each of us. His photos are mysterious, containing the thrill of not knowing what will happen next, and always infused with the light and shadow of cityscapes that are somehow nostalgic. These are things that may be shared as a visual record by people of many nations and generations.

(Originally published in Japanese on August 17, 2017. Banner photo: “Kiroku no. 19” [Record No. 19], 2011, depicts Moriyama taking a photo on the right. © Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation. With thanks to the Taka Ishii Gallery and Photobook Diner Megutama.)

No comments:

Post a Comment