New Again: Ridley Scott

By Elizabeth Weitzman

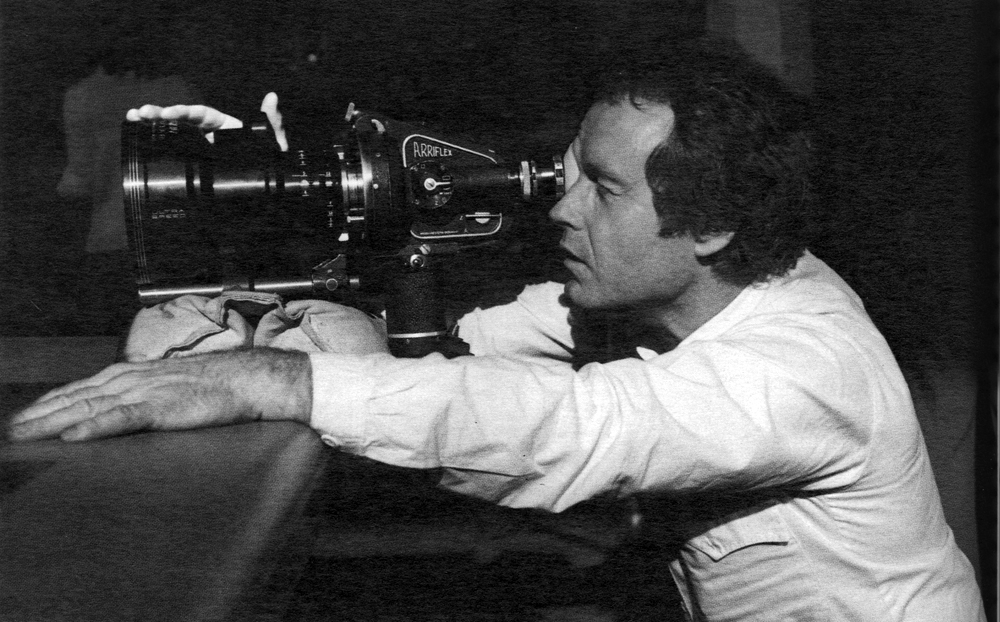

According to Deadline, Ridley Scott is set to receive a lifetime achievement award at the 69th Annual Directors Guild of America Awards in February of next year. We think the 79-year-old British director is an excellent choice; his résumé is among the most prolific and genre-defying in Hollywood, with credits ranging from Alien to Thelma & Louise. Plus, it’s a fitting time to reflect on Scott’s legendary career with the long-awaited release of Alien: Covenant on the horizon this spring. According to DGA President Paris Barclay, “Ridley’s groundbreaking methods and peerless directing instincts have brought to life some of the most memorable films of our time. … Over the course of four decades, his trailblazing career has demonstrated the impact and importance of the director’s singular vision.”

In honor of Scott’s DGA recognition, we’re reprinting his feature from the February 2001 issue of Interview. Following the massive success of Gladiator the year prior, he was not resting on his laurels; he was already at work on Hannibal, the Silence of the Lambs sequel, which would go on to break box office records later that year. While the new millennium marked a resurgence in Scott’s career, the previous decade had been marred by a string of critical and commercial disappointments. In this interview, Scott touches on coping with failure, his British indifference to the Academy Awards, and what allows him to be celebrated across genres. —Frank Chlumsky

Ridley Scott: He Proves that the Greatest Adventures are Personal

By Elizabeth Weitzman

We’ve followed him to the darkest depths of outer space (Alien, 1979) and the most liberating stretch of the open road (Thelma & Louise, 1991). We’ve explored the sweeping past (The Duellists, 1977) and the suffocating future (Blade Runner, 1982) and the reason we’re always ready to tag along is that, unlike many Hollywood directors, Ridley Scott—who is British-born and bred— finds the personal within larger-than-life stories.

Of course, when you overturn stones for a living, you’re bound to find something squirmy underneath. For many audience members, that unwelcome surprise was 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), Scott’s loudly scorned follow-up to Thelma & Louise. His next projects, White Squall (1996) and G.I. Jane (1997), received similar snubs.

But the beauty of living big is that while you may fall hard, you’re always primed to come roaring back. And so, last year, Scott swooped us up and dropped us right in the middle of ancient Rome, characteristically honoring both the glorious grandeur and the humanizing minutiae of a Gladiator‘s life. With barely a pause for breath, he made an appointment with a certain Dr. Lecter, whom, he believed, had kept his mouth shut for too long. Hannibal arrives in theaters this month, because if there’s one thing Ridley Scott can’t stand, it’s silence.

ELIZABETH WEITZMAN: Each movie you’ve made has taken audiences on a new kind of adventure. Do you look at them that way?

RIDLEY SCOTT: Yes, but ideally, all movies do that. Every film you see should at least bring you on a psychological adventure.

WEITZMAN: Your films are all so different. Do you think of them as having any common link?

SCOTT: Only in the sense that there is no link. Each time I direct, I search for a fresh experience and a fresh meaning. They say nothing’s new anymore; that there are only seven original ideas in the world. That sounds rather depressing, but I’ve got a funny feeling it’s more or less accurate. So it’s got to be the way you look at things.

WEITZMAN: You’ve already blown out the boundaries of several genres.

SCOTT: Definitely. But what you come to realize is that nothing matters more than characters and story. Creating a “genre” world, whether it’s a sci-fi or period epic, is relatively easy once you’ve got that figured out.

WEITZMAN: How do you go about creating those worlds?

SCOTT: Well, it’s dressing, but dressing I love to do, because I’m good at it. I sit there and think about what life would be like for a Roman general in 175 A.D. What’s it like to be standing in a coliseum, about to confront 5,000 people who think you’re a barbarian? Once you’ve really felt it, you can start to melt it down into textures and smells—and a lot of dirt! Then you mix the dirt with the emotion.

WEITZMAN: You’ve just made the sequel to The Silence of the Lambs (1991), and you’ve seen other directors continue your thread. What was your opinion of the later Alien movies?

SCOTT: They were good. But you can never repeat the original essence of that creature once it’s been seen. The key to the first one was that the beast was so unique, it was heart-stopping. Although, would I have done the sequel? Absolutely. I created it, so I was surprised when they planned to make another one and I hadn’t heard about it.

WEITZMAN: Did that experience give you any particular insights coming into Hannibal?

SCOTT: Nah. Silence was so well done I couldn’t forget it. But Hannibal takes on a life of it’s own. It goes in such a different direction.

WEITZMAN: Your production’s been shrouded in secrecy. Can you tell me a little about it?

SCOTT: It’s 10 years later, and Hannibal is on the loose. There’s been silence from him for a decade, and we’re meeting Clarice in a new part of her life. It’s really a psychological thriller, and even a love story, I think.

WEITZMAN: A love story? Between Hannibal and Clarice?

SCOTT: [laughs] Maybe love is too specific. Affection and respect is probably more appropriate.

WEITZMAN: When you make a film, is your goal to look for personal answers, to make a great piece of art, or to entertain?

SCOTT: You just listed my three prime motivations! Certainly, part of the process is to be an entertainer. I know Hollywood pictures elicit a certain amount of disdain, but there are some pretty good mainstream movies out there. As a director, if you’re strict about retaining your creative freedoms within the confines of a low budget, you accept that you’ll have a smaller audience. But the kind of material I like to work on, unfortunately, isn’t inexpensive. So I have to put on at least three hats in pulling them together.

WEITZMAN: The three hats being…

SCOTT: Creative, commerce, and probably, somewhere in there, artistry. [laughs]

WEITZMAN: Have you ever made a compromise on-screen that you regretted?

SCOTT: No. Never. Well… Yes, but only driven by myself. You get impatient with your own material, so the danger is to shave it down so fast and hard that you remove the heart of the character.

WEITZMAN: When did you do that?

SCOTT: Legend (1985). And I compromised on Blade Runner in certain areas, which I shouldn’t have done. It was film noir—you can’t pull back from that and have a happy ending, or get into voice-overs, because during the film the audience will find out, and if they don’t, they’re stupid, and they shouldn’t be watching the movie, anyway.

WEITZMAN: Do you blame the studio for those changes?

SCOTT: Oh, no. There isn’t a “them and us” as far as I’m concerned. I have enormous respect for the studios—they’re paying me to have a jolly good time making my vision of what we’ve agreed on. All creative minds have to deal with the people who are paying the bills. As you get more experienced, risks gradually shift into judgment calls. When I did my first feature, I’d already made about 2,000 commercials. So, by the time I entered the world of film, I was a relatively responsible fellow.

WEITZMAN: But when you made Blade Runner, you must have been frustrated trying to convince studio execs to accept your dark fantasy.

SCOTT: Yeah. I wasn’t used to sharing my vision at that point, because I hadn’t really worked in Hollywood yet. I had to go through the irritating process of proving myself all over again.

WEITZMAN: Was that the experience that led you to be more accepting of compromise?

SCOTT: No, I think Legend did that. Blade Runner was hugely disappointing for me. I thought I’d made a pretty special film, and I was really stricken when only a few diehards got it. But then I went down another risky route, because I had it in my head to do a live action fairytale. I wondered if audiences were ready for it though, because that was the experience I’d been through with Blade Runner—basically, people weren’t prepared for the presentation. But then I slowly saw it rebound.

WEITZMAN: What do you mean?

SCOTT: I started to notice that the videos on MTV were getting darker. It was always raining, the streets were always shining, and there was smoke coming off them. So I thought, Ah-hah, it’s finally struck ground! I was watching Blade Runner‘s influence appear.

WEITZMAN: That must have been rewarding.

SCOTT: I was amused by it. And taking the next step from there was doing Legend. It was as huge risk. Did people get it? No, they didn’t, even though there was an enormous amount of absolutely brilliant work in it.

WEITZMAN: Your movies immediately after Thelma & Louise—like 1942—were received rather negatively. Did you go through any periods of insecurity during those years?

SCOTT: Yes. But I learned not to let it overwhelm me. You can sit and dwell on something and let depression consume you, or you can just shut it out.

WEITZMAN: Still, did Gladiator’s success feel like any kind of validation for you?

SCOTT: Oh, sure. And I knew where we were headed about three weeks into it. I thought, Shit! We’ve got something here.

WEITZMAN: What would it mean to you to win an Academy Award for Gladiator?

SCOTT: [laughs] I’m British and we don’t think that way. Of course, if it occurs, great, absolutely fantastic, couldn’t wish for anything better.

WEITZMAN: Off the set, are you a danger-seeker?

SCOTT: Nope. I like to muck about in the garden. I think the job’s got everything else, thank you very much.

WEITZMAN: Cinematically speaking, what’s left for you to conquer?

SCOTT: I’m looking at a pirate movie right now. But I’m also thinking about going back to my first love, which is Westerns. I know it’s odd, because I’m European, but I was obsessed with cowboys when I was a kid. I was a very keen horseman. I even started hunting. I never saw a fox caught in my life, and I fell a couple times and thought, “Wait a minute—this is daft!”

WEITZMAN: Did you do a lot of risk-taking when you were a kid?

SCOTT: I was always outside, falling into the ocean or climbing rocks. It concerns me that you see kids sitting in front of a television screen tapping buttons now, when I’d be out waving a wooden stick around as a rifle, defending a pile of mud. Of course, times change, but I hope computers aren’t the only option today.

WEITZMAN: Movies are, too.

SCOTT: That’s no alternative, either. Experiencing adventures in your own imagination is what’s key.

WEITZMAN: Do you look at directing itself as being an adventure?

SCOTT: Totally. We’re going off and creating other worlds. In a way, we’re really the last explorers.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE FEBRUARY 2001 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

Two weeks ago on Dr. Phil, Shelley Duvall made her first public appearance since retiring in 2002, and revealed that she has a mental illness, leaving audiences baffled and concerned. Duvall told Dr. Phil‘s host Phil McGraw (a formerly licensed psychologist), that her Popeye costar Robin Williams is still alive as a shapeshifter and that she has a “whirling disk” implanted inside of her leg, among other things. She concluded, “I’m very sick. I need help.” According to Deadline, the Actors Fund has reached out to Duvall’s family to assist in her recovery after Phil McGraw announced that the actor refused treatment. The Dr. Phil episode, which has since been removed from the show’s website, angered audiences, who felt that The Shining actor had been exploited. Vivian Kubrick, daughter of Stanley Kubrick, who directed Duvall in The Shining, tweeted demanding a boycott of the episode, calling it “purely a form of lurid and exploitative entertainment.”

As a nod to cheerier times, we’ve reprinted Shelley Duvall’s cover story fromInterview‘s September 1977 issue. The actress was set to begin filming The Shining with Jack Nicholson within the next few months, entering what would become the peak of her career. In the wake of the arrest of infamous serial killer “Son of Sam,” Duvall told Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello about summering in East Hampton, being discovered on location as an actress, and her ironic fear of horror movies. —Natalia Barr

Shelley Duvall Before The Shining

By Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello

[Redacted by Chris Hemphill]

Thursday, August 11, 1977, 8:30 p.m. Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello are dining with Shelley Duvall, the star of Three Women, at Quo Vadis, 26 E. 63 St. Shelley is wearing a bright pink cotton dress that flares out below the hips, bright green linen boots, and a bright pink and green silk shawl. She speaks slowly and softly.

[Tape #1, Side A.]

ANDY WARHOL: This is a whole new table. I’ve never sat on this side before. Are you staying out in East Hampton most of the time?

SHELLEY DUVALL: Yes, for most of the summer. I come back about two days a week usually.

WARHOL: Son of Sam was on his way out there.

DUVALL: I just heard!

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How could a Berkowitz kill a Moskowitz?

DUVALL: That’s the first thing I thought.

WARHOL: It’s too terrible.

BOB COLACELLO: What would you like to eat?

[orders]

WARHOL: Where did you learn French?

DUVALL: Not from my father.

WARHOL: Duvall is a French name.

DUVALL: My father’s half-French and I’m whatever’s left.

WARHOL: Where were you born?

DUVALL: I was born in Fort Worth but I never lived there. I was visiting my grandmother at the time.

WARHOL: I don’t understand.

DUVALL: My mother was visiting my grandmother when I was born. But I grew up in Houston. I lived there until ’73 and then I moved to Los Angeles.

WARHOL: When did we meet?

DUVALL: You met me in 1970 when I’d just finished Brewster McCloud and was about to do McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Bill Worth told me, “Come down to the Factory and meet Andy Warhol,” and we got there and you weren’t there but we looked at pictures. And I remember the time you told me, “I stayed home from Elaine’s birthday party to watch you on Dick Cavett.” I was so flattered!

COLACELLO: You’re such a charmer, Andy.

WARHOL: But it was true.

COLACELLO: So what’s this new movie you’re doing with Jack [Nicholson]?

DUVALL: It’s from a novel written by Stephen King, who wrote Carrie. It’s calledThe Shining and we start shooting somewhere between December 1 and February 1. Stanley Kubrick’s writing the script now. He’s directing and it’ll be shot in London and Switzerland for 15 to 25 weeks—a long shoot.

COLACELLO: Is it a big cast?

DUVALL: No, it’s Jack and myself and a five-year-old boy, basically. And there’s a psychiatrist and an ex-gardener at the place where we’re caretakers. It’s very frightening. When I first heard of it I was wondering why Stanley Kubrick would want to do this film and then I read the book and it turns out, I think, to be really primal about fears and about the fears that one has in a relationship with another person.

WARHOL: It sounds like it could be a Robert Altman film, too. Three Women was terrific.

DUVALL: Bob knows me very well and he knows my limitations.

WARHOL: That story was fascinating.

DUVALL: I loved that story. That was an actual dream that Bob had. He had the dream on a Saturday night and he called me up on Sunday morning and said, “Shelley. I just had this incredible dream. Part of the dream was that I woke up and told my wife and wrote it all down on a yellow legal pad and called my production assistant and said, ‘I want you to scout locations for me,'” and then he woke up and discovered he hadn’t told his wife and he hadn’t written it down. It’s amazing—within a week he had the money for the film and we started shooting a month later.

WARHOL: Janice Rule is one of my favorite actresses but her style of acting was so different from yours and Sissy Spacek‘s.

DUVALL: I was just going to tell you it was actually just two women in the dream—Sissy and I. But I think someone like Bergman or Antonioni had already done a film called Two Women.

WARHOL: No, it was Sophia Loren. That was the one where she came out of the ocean. She won an Academy Award for it.

COLACELLO: Did you ever think you wanted to be an actress?

DUVALL: Never.

COLACELLO: How did you get started?

DUVALL: It’s a long story but I’ll tell you. I was living with my artist boyfriend at his parents’ house in Houston and we had a lot of parties and people would come who we didn’t know and his parents’ friends would come—they were really good parents—and one day I was giving a party and these three gentlemen came in and I said, “Come in, fix yourself a drink, make yourself at home,” and I continued showing all my friends Bernard’s new paintings, telling them what the artist was thinking. And they said they had some friends who were patrons of the arts who’d like to see the paintings so I made an appointment, brought the paintings up and showed them one by one. I lugged 35 paintings up there. And instead of selling some paintings I wound up getting into a movie.

WARHOL: They were testing you out?

DUVALL: Yes, they said, “How would you like to be in a movie?” and I thought, “Oh, no, a porno film,” because I’d been approached for that when I was 17 in a drugstore.

WARHOL: What did you do?

DUVALL: The guy left me with the bill for the Coca-Cola. So this time I said, “No, thank you,” and they called my parents’ house and got hold of me and after a while we became such good friends that I had no fear. I said, “I’m not an actress.” They said, “Yes, you are.” Finally, I said, “All right, if you think I’m an actress I guess I am.”

WARHOL: But what were they doing there?

DUVALL: They were on location.

WARHOL: But what made them come to the house? Were they just looking for something to do?

DUVALL: Somebody at the party had called them up and told them if they were bored in Houston we gave a lot of parties. When the film was over I thought it was just an interlude in my life. But three months later I started work on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Actually during Brewster McCloud I’d already signed a five-year contract.

WARHOL: I guess things really do happen at parties.

[contracts]

COLACELLO: But you never studied acting?

DUVALL: I went to Lee Strasberg a few years ago because I’d heard such good things about him but I went to two lessons and it just wasn’t for me. That’s one piece of advice Robert Altman gave me at the very beginning—never take lessons and don’t take yourself seriously.

WARHOL: He’s right. It’s all magic. The problem is knowing how to keep it once you get it.

DUVALL: I make my own decisions. And I never turn down anything without reading it. Other than that… I’m sort of at a loss for words. It was hard to move here, actually.

WARHOL: You mean you’re living here for real?

DUVALL: I moved here in October.

WARHOL: To East Hampton?

DUVALL: No, to New York from L.A. East Hampton’s just a summer place.

WARHOL: Some people live there year-round now

DUVALL: I like that idea. I think it would be just as nice in the spring and fall as in the summer. Our place looks like Japan. It’s got those short needlepines, little pebbles and everything.

WARHOL: Montauk doesn’t have much of a beach but it’s very beautiful. It’s all rocks.

DUVALL: I want to see the lighthouse.

WARHOL: If you’d seen Peter Beard’s place you’d be so sad now. It just burned down last week with all his work inside.

DUVALL: How terrible. Was it lightning?

WARHOL: No, the boiler room.

DUVALL: God, the boiler room! You should read The Shining.

WARHOL: Does it happen in a boiler room?

DUVALL: You’ll see. It’s frightening.

WARHOL: Carrie was so good.

DUVALL: I still haven’t seen it. Scary movies frighten me. I still haven’t seen The Exorcist.

WARHOL: It’s really good. It isn’t even scary. It’s just intelligent.

DUVALL: I like to see just about every movie that comes out that strikes my fancy.

WARHOL: I’m always worrying about bombs in movie theaters, though. My favorite kind of movies are unsuccessful ones because there’s no one there. And then I like…

[End of Side A.]

[Tape #1, Side B.]

DUVALL: …The Omen.

COLACELLO: Why did you move to New York from L.A.?

DUVALL: For several reasons. I’d always wanted to move to New York, from the first time I came here. And then I guess Paul [Simon] was an extra added attraction—a New Yorker boyfriend.

COLACELLO: That’s a nice way of putting it. He’s working so much now.

DUVALL: He’s always working. There’s so much energy here. That’s why I like it, despite everything.

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How can people see something on TV and then they can’t wait to read about it in the newspaper? Why is that?

DUVALL: Maybe it’s more real.

WARHOL: Maybe.

DUVALL: New Yorkers have a fascination with the daily paper. I could never understand that when I came here. And I could never understand how people get up to see “The Today Show.”

WARHOL: It’s easy if you have a pushbutton. It’s great. And if you turn it on at seven you see the news three or four times which is even better—all the repeats.

DUVALL: I did an interview with Gene Shalit and I never saw it because I could never wake up early enough.

COLACELLO: Would you like some dessert?

DUVALL: I’m looking over at the chocolate mousse but…

WARHOL: I was supposed to go to the pimple doctor this morning and I never went.

[pimple doctors]

DUVALL: Well, everybody’s got something about them. But did you hear about the guy with no feet?

WARHOL: No, who?

DUVALL: I’m just kidding. But here we’re complaining about pimples and…

WARHOL: Oh, I know. We’re so lucky.

DUVALL: We really are.

WARHOL: So many people have so many problems. When you think that health is wealth, you’re so grateful just to be normal, more or less. Aren’t you?

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

Two weeks ago on Dr. Phil, Shelley Duvall made her first public appearance since retiring in 2002, and revealed that she has a mental illness, leaving audiences baffled and concerned. Duvall told Dr. Phil‘s host Phil McGraw (a formerly licensed psychologist), that her Popeye costar Robin Williams is still alive as a shapeshifter and that she has a “whirling disk” implanted inside of her leg, among other things. She concluded, “I’m very sick. I need help.” According to Deadline, the Actors Fund has reached out to Duvall’s family to assist in her recovery after Phil McGraw announced that the actor refused treatment. The Dr. Phil episode, which has since been removed from the show’s website, angered audiences, who felt that The Shining actor had been exploited. Vivian Kubrick, daughter of Stanley Kubrick, who directed Duvall in The Shining, tweeted demanding a boycott of the episode, calling it “purely a form of lurid and exploitative entertainment.”

As a nod to cheerier times, we’ve reprinted Shelley Duvall’s cover story fromInterview‘s September 1977 issue. The actress was set to begin filming The Shining with Jack Nicholson within the next few months, entering what would become the peak of her career. In the wake of the arrest of infamous serial killer “Son of Sam,” Duvall told Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello about summering in East Hampton, being discovered on location as an actress, and her ironic fear of horror movies. —Natalia Barr

Shelley Duvall Before The Shining

By Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello

[Redacted by Chris Hemphill]

Thursday, August 11, 1977, 8:30 p.m. Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello are dining with Shelley Duvall, the star of Three Women, at Quo Vadis, 26 E. 63 St. Shelley is wearing a bright pink cotton dress that flares out below the hips, bright green linen boots, and a bright pink and green silk shawl. She speaks slowly and softly.

[Tape #1, Side A.]

ANDY WARHOL: This is a whole new table. I’ve never sat on this side before. Are you staying out in East Hampton most of the time?

SHELLEY DUVALL: Yes, for most of the summer. I come back about two days a week usually.

WARHOL: Son of Sam was on his way out there.

DUVALL: I just heard!

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How could a Berkowitz kill a Moskowitz?

DUVALL: That’s the first thing I thought.

WARHOL: It’s too terrible.

BOB COLACELLO: What would you like to eat?

[orders]

WARHOL: Where did you learn French?

DUVALL: Not from my father.

WARHOL: Duvall is a French name.

DUVALL: My father’s half-French and I’m whatever’s left.

WARHOL: Where were you born?

DUVALL: I was born in Fort Worth but I never lived there. I was visiting my grandmother at the time.

WARHOL: I don’t understand.

DUVALL: My mother was visiting my grandmother when I was born. But I grew up in Houston. I lived there until ’73 and then I moved to Los Angeles.

WARHOL: When did we meet?

DUVALL: You met me in 1970 when I’d just finished Brewster McCloud and was about to do McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Bill Worth told me, “Come down to the Factory and meet Andy Warhol,” and we got there and you weren’t there but we looked at pictures. And I remember the time you told me, “I stayed home from Elaine’s birthday party to watch you on Dick Cavett.” I was so flattered!

COLACELLO: You’re such a charmer, Andy.

WARHOL: But it was true.

COLACELLO: So what’s this new movie you’re doing with Jack [Nicholson]?

DUVALL: It’s from a novel written by Stephen King, who wrote Carrie. It’s calledThe Shining and we start shooting somewhere between December 1 and February 1. Stanley Kubrick’s writing the script now. He’s directing and it’ll be shot in London and Switzerland for 15 to 25 weeks—a long shoot.

COLACELLO: Is it a big cast?

DUVALL: No, it’s Jack and myself and a five-year-old boy, basically. And there’s a psychiatrist and an ex-gardener at the place where we’re caretakers. It’s very frightening. When I first heard of it I was wondering why Stanley Kubrick would want to do this film and then I read the book and it turns out, I think, to be really primal about fears and about the fears that one has in a relationship with another person.

WARHOL: It sounds like it could be a Robert Altman film, too. Three Women was terrific.

DUVALL: Bob knows me very well and he knows my limitations.

WARHOL: That story was fascinating.

DUVALL: I loved that story. That was an actual dream that Bob had. He had the dream on a Saturday night and he called me up on Sunday morning and said, “Shelley. I just had this incredible dream. Part of the dream was that I woke up and told my wife and wrote it all down on a yellow legal pad and called my production assistant and said, ‘I want you to scout locations for me,'” and then he woke up and discovered he hadn’t told his wife and he hadn’t written it down. It’s amazing—within a week he had the money for the film and we started shooting a month later.

WARHOL: Janice Rule is one of my favorite actresses but her style of acting was so different from yours and Sissy Spacek‘s.

DUVALL: I was just going to tell you it was actually just two women in the dream—Sissy and I. But I think someone like Bergman or Antonioni had already done a film called Two Women.

WARHOL: No, it was Sophia Loren. That was the one where she came out of the ocean. She won an Academy Award for it.

COLACELLO: Did you ever think you wanted to be an actress?

DUVALL: Never.

COLACELLO: How did you get started?

DUVALL: It’s a long story but I’ll tell you. I was living with my artist boyfriend at his parents’ house in Houston and we had a lot of parties and people would come who we didn’t know and his parents’ friends would come—they were really good parents—and one day I was giving a party and these three gentlemen came in and I said, “Come in, fix yourself a drink, make yourself at home,” and I continued showing all my friends Bernard’s new paintings, telling them what the artist was thinking. And they said they had some friends who were patrons of the arts who’d like to see the paintings so I made an appointment, brought the paintings up and showed them one by one. I lugged 35 paintings up there. And instead of selling some paintings I wound up getting into a movie.

WARHOL: They were testing you out?

DUVALL: Yes, they said, “How would you like to be in a movie?” and I thought, “Oh, no, a porno film,” because I’d been approached for that when I was 17 in a drugstore.

WARHOL: What did you do?

DUVALL: The guy left me with the bill for the Coca-Cola. So this time I said, “No, thank you,” and they called my parents’ house and got hold of me and after a while we became such good friends that I had no fear. I said, “I’m not an actress.” They said, “Yes, you are.” Finally, I said, “All right, if you think I’m an actress I guess I am.”

WARHOL: But what were they doing there?

DUVALL: They were on location.

WARHOL: But what made them come to the house? Were they just looking for something to do?

DUVALL: Somebody at the party had called them up and told them if they were bored in Houston we gave a lot of parties. When the film was over I thought it was just an interlude in my life. But three months later I started work on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Actually during Brewster McCloud I’d already signed a five-year contract.

WARHOL: I guess things really do happen at parties.

[contracts]

COLACELLO: But you never studied acting?

DUVALL: I went to Lee Strasberg a few years ago because I’d heard such good things about him but I went to two lessons and it just wasn’t for me. That’s one piece of advice Robert Altman gave me at the very beginning—never take lessons and don’t take yourself seriously.

WARHOL: He’s right. It’s all magic. The problem is knowing how to keep it once you get it.

DUVALL: I make my own decisions. And I never turn down anything without reading it. Other than that… I’m sort of at a loss for words. It was hard to move here, actually.

WARHOL: You mean you’re living here for real?

DUVALL: I moved here in October.

WARHOL: To East Hampton?

DUVALL: No, to New York from L.A. East Hampton’s just a summer place.

WARHOL: Some people live there year-round now

DUVALL: I like that idea. I think it would be just as nice in the spring and fall as in the summer. Our place looks like Japan. It’s got those short needlepines, little pebbles and everything.

WARHOL: Montauk doesn’t have much of a beach but it’s very beautiful. It’s all rocks.

DUVALL: I want to see the lighthouse.

WARHOL: If you’d seen Peter Beard’s place you’d be so sad now. It just burned down last week with all his work inside.

DUVALL: How terrible. Was it lightning?

WARHOL: No, the boiler room.

DUVALL: God, the boiler room! You should read The Shining.

WARHOL: Does it happen in a boiler room?

DUVALL: You’ll see. It’s frightening.

WARHOL: Carrie was so good.

DUVALL: I still haven’t seen it. Scary movies frighten me. I still haven’t seen The Exorcist.

WARHOL: It’s really good. It isn’t even scary. It’s just intelligent.

DUVALL: I like to see just about every movie that comes out that strikes my fancy.

WARHOL: I’m always worrying about bombs in movie theaters, though. My favorite kind of movies are unsuccessful ones because there’s no one there. And then I like…

[End of Side A.]

[Tape #1, Side B.]

DUVALL: …The Omen.

COLACELLO: Why did you move to New York from L.A.?

DUVALL: For several reasons. I’d always wanted to move to New York, from the first time I came here. And then I guess Paul [Simon] was an extra added attraction—a New Yorker boyfriend.

COLACELLO: That’s a nice way of putting it. He’s working so much now.

DUVALL: He’s always working. There’s so much energy here. That’s why I like it, despite everything.

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How can people see something on TV and then they can’t wait to read about it in the newspaper? Why is that?

DUVALL: Maybe it’s more real.

WARHOL: Maybe.

DUVALL: New Yorkers have a fascination with the daily paper. I could never understand that when I came here. And I could never understand how people get up to see “The Today Show.”

WARHOL: It’s easy if you have a pushbutton. It’s great. And if you turn it on at seven you see the news three or four times which is even better—all the repeats.

DUVALL: I did an interview with Gene Shalit and I never saw it because I could never wake up early enough.

COLACELLO: Would you like some dessert?

DUVALL: I’m looking over at the chocolate mousse but…

WARHOL: I was supposed to go to the pimple doctor this morning and I never went.

[pimple doctors]

DUVALL: Well, everybody’s got something about them. But did you hear about the guy with no feet?

WARHOL: No, who?

DUVALL: I’m just kidding. But here we’re complaining about pimples and…

WARHOL: Oh, I know. We’re so lucky.

DUVALL: We really are.

WARHOL: So many people have so many problems. When you think that health is wealth, you’re so grateful just to be normal, more or less. Aren’t you?

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

No comments:

Post a Comment