“I Wanted to Make This Man Make Sense”

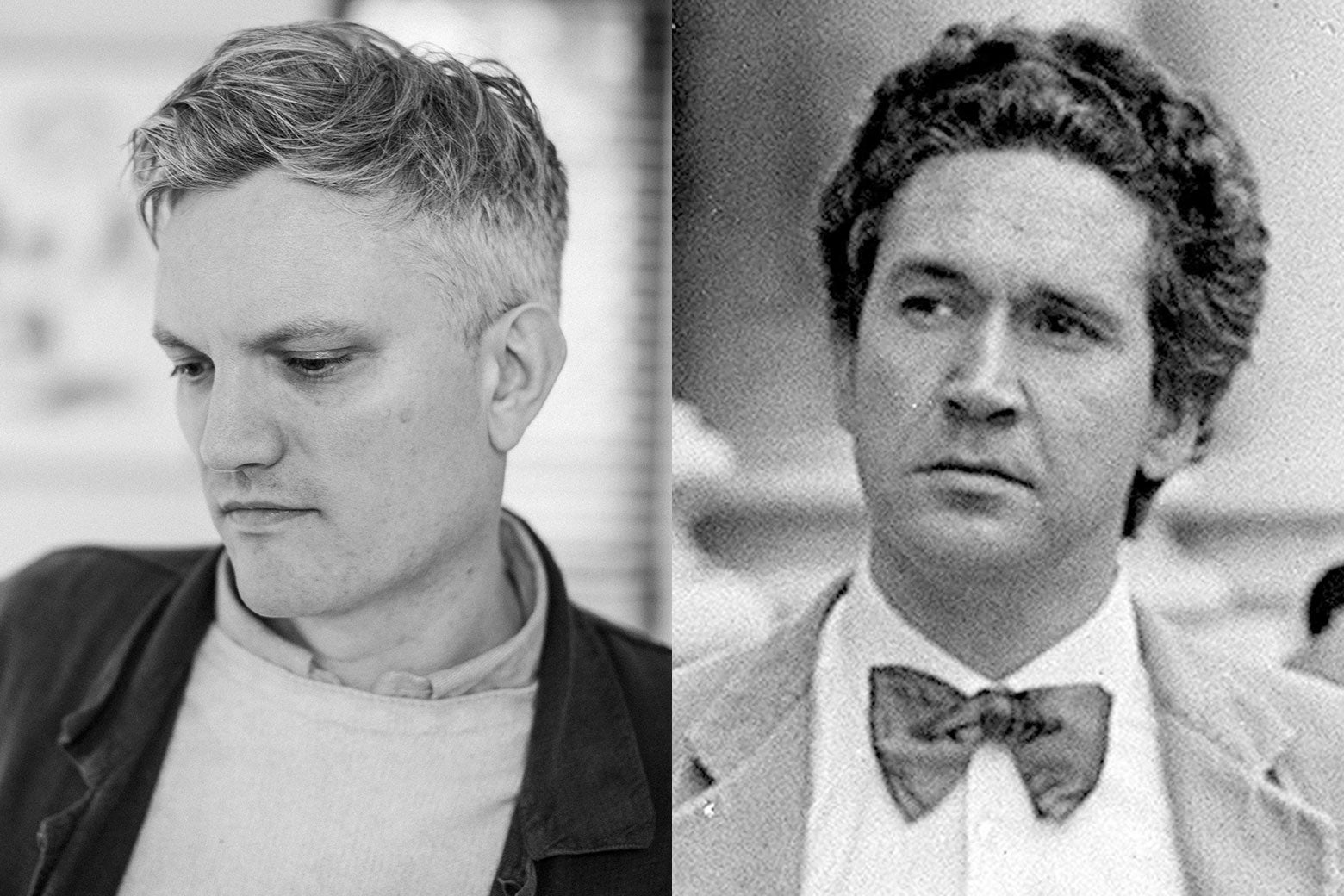

A conversation with Mark O’Connell about true crime and the human desire for a story that makes sense of it all.

JUNE 29, 2023

Not many people can say that they frequently walk past a known murderer on the street, but the residents of central Dublin are among them. Malcolm Macarthur, one of the most notorious killers in the history of modern Ireland, can often be spotted strolling the sidewalks, taking the bus, at the library, and even attending literary events. These days he’s a nattily attired and cultured gentleman in his 70s, but in 1982, during a misbegotten scheme to rob a bank, he fatally beat a nurse with a hammer, shot a farmer in the face with a shotgun, and caused a national scandal when he was arrested at the home of Ireland’s attorney general.

Writer and Slate contributor Mark O’Connell also lives in Dublin, and on several occasions he’d spotted Macarthur—who was released in 2012 after serving 30 years of a life sentence—out and about. O’Connell intercepted Macarthur on a Dublin street during the pandemic and persuaded the murderer to grant him a series of interviews. Before he could be tried, Macarthur had pleaded guilty, so he never testified. Indeed, O’Connell writes in his remarkable new book, A Thread of Violence, Macarthur’s crimes were the subject of books, documentaries, and countless newspaper and magazine articles, but “I had never heard or read so much as a word from his own mouth about the things he had done, or his reasons for having done them.”

The result is a book that tells the true story of a crime while scrutinizing our desire for such true-crime stories and the often simplistic explanations they offer for the terrible things people do. I spoke with O’Connell about what he sought and what he found in his conversations with this enigmatic criminal. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Laura Miller: The key points that seem to have made the Macarthur story so mythic in Ireland are his class and his hiding out at the attorney general’s house. Is that right?

Mark O’Connell: Yeah, I think that’s it. Little is known about this man, but the story gets told again and again. He’s a bow tie–wearing toff with a tweed jacket, and there’s his proximity to power and privilege. And there was suspicion about the relationship between the attorney general and this murderer. There was a sense of glimpsing a roiling sea of corruption through the aperture of this one murder. Turned out, ironically enough, that the prime minister had nothing to do with it. But I think that’s what lends Macarthur this aura of sinister revelation: He is a creature of the establishment. This is how he thinks of himself, even to this day. He hasn’t quite relinquished this sense of himself as a connected man, a respectable person.

A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder

By Mark O’Connell. Doubleday.

Do you think that part of the public fascination comes from the belief that because the people he murdered were a nurse and a farmer, and therefore not members of his own class, he must have thought that they were disposable?

I think there’s a dimension of that. I was inclined at first to read it that way, as a class allegory, with this upper-class vampire figure who murders two young working people. But as I started to write the book, those allegorical readings of the case—they didn’t entirely fall away, but the thing I found with Macarthur is that any kind of narrative slot that you try to put him in, he doesn’t quite fit. Any kind of allegorical reading or political reading obscures as much or more than it reveals. It was the same with even psychological readings. You probably noticed when you were reading it that the language of psychiatry does not come into the book at all.

That’s very striking.

Just as people would want to explain it in terms of a class allegory or a historical allegory or to make it make sense in terms of Ireland, they would similarly want to make it make sense in terms of, “This guy’s clearly a pathological narcissist,” or, “He’s autistic.” Loads of different interpretive frames were put on his behavior. Some of those, as I say, may be right, but it’s a little too easy. Or, rather, it’s not the language that is useful for me in what I’m trying to do. The more time I spent with him, the less convinced I was that there was any one way of explaining him. If I had just spent two hours with him, I probably could have walked away and gone, “Yeah, I have the measure of this guy.” But you spend dozens and dozens of hours in a room with someone and they, in a way, become less clear.

He’s definitely a bit of a weirdo, but not in a way that you would think would lead to him murdering someone. He seems like an affected guy who just wants to read newspapers and books and listen to the radio and not really do anything with his life. He appears harmless. I suppose he was a person who was determined to get what he wanted, which was enough money so that he didn’t have to work. And when he came up against any interference to his plan, he just didn’t know what to do except to obliterate it.

He wants to see himself as a harmless man. I wouldn’t use that phrase about him. I don’t think he is harmless. But yes, some of the nicest people I know, they have titles and they’re very well-rounded people, and they’re the products of very expensive educations and generations of free time and cultivation and culture. Macarthur is kind of like that. He is a nice person. He prides himself on being polite and acting with decency. But these totally senseless and brutal murders happened because that was threatened. That position—of privilege and freedom and wafting about reading books and being a cultured person living this cultivated life—was threatened because of his lack of money. So rather than getting a job, rather than getting out there and rolling up his sleeves and living off his own labor, he committed murder. In a way, the hidden violence beneath those social arrangements was made explicit in that moment. I’m interpreting it there in a single way, which is what I’m trying not to do in the book.

You become a character in the book, partly because at the beginning you’re searching for him. Finally, there is the moment when you do run into him on the street, and you engage him in conversation. Then—immediately after Macarthur has told you that people hardly ever recognize him, and when they do, they’re not usually hostile—a man recognizes him and is very hostile. The man takes a photo, and you think, “Uh-oh, somewhere there’s a picture of me talking with Macarthur.” Now you’re part of the story, instead of a guy who’s trying to find the story. And it’s a really weird, unsettling moment. This forces the question of what you’re after. In the beginning, you seem to think that if you can draw him out, you will gain some understanding of evil. You will be able to witness it in some way. But maybe I’m wrong about that, and you can clarify.

In a way, that’s a red herring, because the book is not really about evil. “Evil” is a word that seems to explain something, but is actually just pasteboard. It doesn’t explain anything. Part of what I wanted was to make this man make sense. There’s this strange combination of absolute moral otherness—a person who has done these unspeakable things—but also this strange proximity. He comes from not the same social world that I come from, but as I say in the book, it seemed that we might share a language. He’s an intellectual. He’s someone who might have a similar set of references to myself. But none of those explanations for why I wanted to talk to him were all that satisfactory to me. Really what it is, is that I felt he was a good character and this is a really good story. That’s the reason, I think, for every journalistic encounter: because it’s a good character and a good story. But there is a moral dimension to that.

Later, once you become engaged with him and you’re far along in this project, there’s a moment where you want to feel that he is aware of the horror of what he’s done. You’ve described the victims’ lives. Bridie Gargan, the nurse, and Dónal Dunne, the farmer, were quite young when he murdered them. They’re both the same age, right?

Twenty-seven, yeah.

They’re total strangers who Macarthur just destroys on his completely misguided path to committing a bank robbery that never happens. They have families who are devastated by their loss, and you want to see him register that enormity in some way, which I think is a common feeling people have toward murderers. What do you think about that desire? Do you feel like that was another blind alley?

I don’t think that I would be able to commit murder, but I think that if I had, I would be morally crushed by it. I would just be absolutely destroyed by it. So, yeah, I did want to see that. I did want to get to some sense of real remorse, not just regret, but real—as I say in the book, I wanted to feel that he was somehow destroyed by the fact of having done what he did. He served 30 years in prison, and he admitted what he did, and so on. So, in a way, he has paid for his crime. But in another sense, I couldn’t shake this feeling that he had got away with it. Morally, he had almost got away with it.

I was haunted and unsatisfied by the sense that he’s not crushed by the weight of these deeds. And then, of course, the book asks, “Why do I want this? Why do I want this from him?” Yes, it’s morally satisfying, but it’s also narratively satisfying. I wanted Raskolnikov, and I did not get it.

He says “I’m not the type of person who is a murderer,” referencing his period in prison, implying that he’s met real murderers there and he’s not like them. But he obviously is a murderer. And now he’s basically living the same life that he was before. He’s the same person that he was before he committed the murder and went to jail! He doesn’t seem transformed by the experience, except materially.

So much of this book is about people wanting a narrative that makes sense. You want a narrative of him suffering remorse. He had a narrative of how he was going to rob a bank, a conviction about how that was going to go, and as soon as Bridie and Dónal presented an obstacle, he had to plow through them to finish the story of him getting the money that he needed. It’s as if the momentum of that story about how he was going to solve his problems was what caused him to do it.

It’s a phrase that he uses in the book, “fixity of purpose.”

Exactly, and now, the story that we usually want to see from someone like him involves some attempt to atone for what he had done.

I don’t know. That might be a Judeo-Christian thing or something. Macarthur says, “Well, what do you want from me?” And of course, he is constantly dissimulating throughout our relationship. But I think there’s something about his refusal to perform remorse, to perform grief about himself or anyone else. I’m not going to say it’s honorable, because it’s anything but honorable, but in a weird way, it’s maybe …

Honest?

Yeah. And it’s very disturbing for that reason, but, yeah.

You write about your struggle with yourself to think of him as real person, because, first, you studied John Banville, an author who turned Macarthur into a fictional character in his novel The Book of Evidence, and second, because you are making a narrative out of him. Meanwhile, you have to correct all these popular narratives about him, because they are part of the story as well.

It is very much a book of competing fictions or competing narratives, and I’m very interested in how reality is just made up of fiction. Stories are power. The way that you shape a story is a way to take power. For the most part, I would let him tell his story, and often that would involve what I thought of as lies, but I would let him do it because I thought that it would be not useful for me to be constantly catching him out, like a crusading TV journalist. But there were moments when I did press the truth. In our relationship, such as it is, there are moments when we have real arguments, where there’s real tension, and often that revolves around me insisting on what I see as the truth. That’s a power move, and I didn’t use it very often, but when I do use it, it’s using the truth as a weapon.

Which of course raises the question of how he responded to your attempt to tell a truthful narrative about him, in which he has no power at all.

I tried to warn him all along that he would not like what I was going to write. He would affect sophistication and say, “Well, of course, you’ve got your own job to do. You’re not just parroting my story,” or whatever.

And when he read the book?

I’ll briefly sketch it to say that he was not happy.

No comments:

Post a Comment