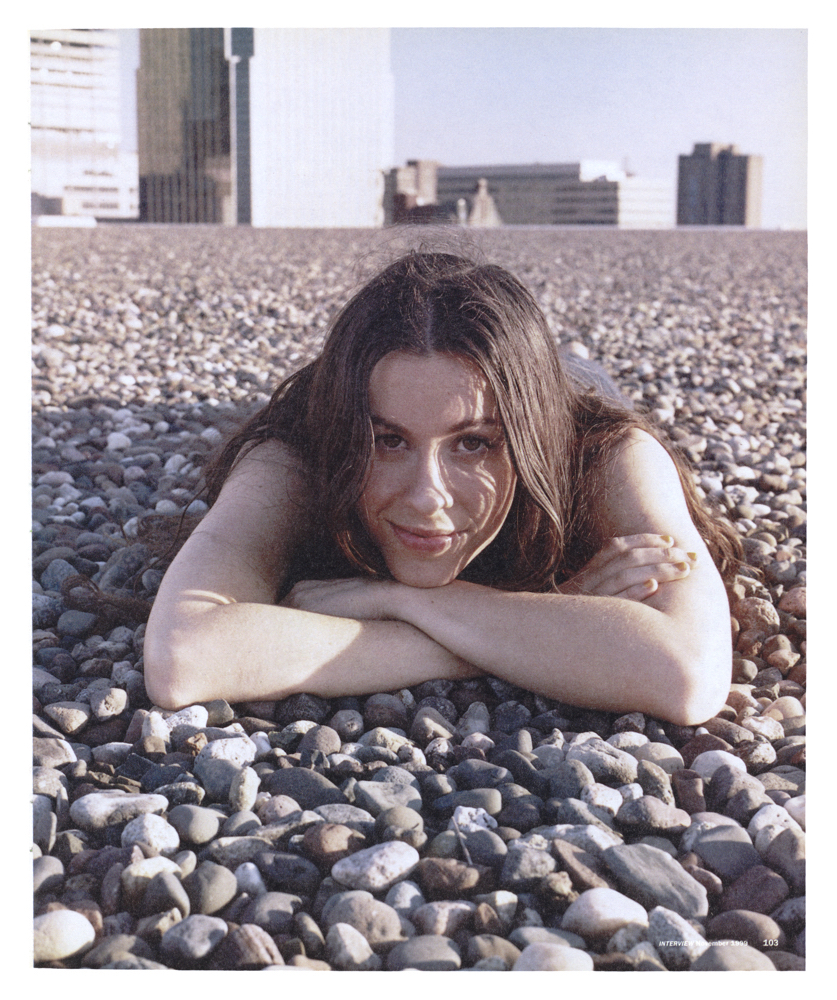

New Again: Alanis Morissette

Twenty years ago, Alanis Morissette released her now-legendary debut album Jagged Little Pill, which went on to earn the Canadian-American singer four 1996 Grammy Awards: Best Female Rock Vocal Performance, Best Rock Song, Best Rock Album, and Album of the Year. During her teenage years, Morissette released two pop albums in Canada, Alanis (1991) and Now is the Time (1992), and after Jagged Little Pill, she continued her path to rock stardom with Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie (1998), Under Rug Swept (2002), So-Called Chaos (2004), Flavors of Entanglement (2008), and Havoc and Bright Lights (2012), earning three more Grammys along the way. But more than a singer, songwriter, guitarist, and producer, Morissette has also honed her talent as an actress. She’s in movies like Dogma and Just Friends, and has made appearances in cult television series like Sex and the City, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and Weeds. As of this week, she’s back with yet another endeavor: a podcast entitled Conversation with Alanis Morissette.

“I have been having these wildly engaging conversations with my mentors and teachers and colleagues privately, quietly and on-goingly in cafes, my kitchen, schools, tour buses, airplanes and the like for so many years,” the multi-hyphenate recently said. “For them to be made public now in the form of this podcast is a dream come true—a stepping out, and a coming home.”

In honor of the podcast’s debut and Jagged Little Pill‘s 20th anniversary (on October 30 she will release a four-disc collector’s edition that includes 10 previously unreleased demos), here we revist a conversation with Morissette in our November 1999 issue.

A Gig Called God

By Elizabeth Weitzman

What if the Almighty were played by a rock star? That’s exactly what Alanis Morissette does in Dogma, Kevin Smith’s new movie, which humanizes religion to such a degree that Walt Disney walked away from it. But even the naysayers can’t stop its materializing in theaters this month.

Here are the things Alanis Morissette has in common with (the Judeo-Christian) God: She’s a creator; her presence is serenely graceful but her words often express flashes of grievous anger; and pretty much every living soul in the Western world knows her name. Here’s one of the things she doesn’t have in common with God: She’s a woman. On the other hand, in this month’s Dogma, Kevin Smith’s terrifically pixilated love letter to divinity, God is officially neither girl nor boy, but still looks like, well, Alanis herself. It’s an inspired piece of casting.

Morissette may have become the foremost symbol of young female passion with her 1995 album Jagged Little Pill, but as last year’s follow-up Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie, affirms, her greatest gifts lie in universal connection; she’s urgently determined to empower anyone who’s been damaged by doubt or pain, regardless of gender or experience. In fact, Morissette is one of the few who holds a place of honor atop music’s Mount Olympus and refuses to indulge in the wasteful separatism of sitting there. Which actually leads up to believe that while she may play a great God, she still does her best work in the role of prophet.

<iframe width=”420″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/NPcyTyilmYY” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen></iframe>

ELIZABETH WEITZMAN: How did you come to be in Dogma?

ALANIS MORISSETTE: Kevin and I had talked about working together, and by the time I was ready, there was one role left—God. I read the script, and it really required me to define what my beliefs were. Anything that triggers me in that way is very exciting.

WEITZMAN: You and Kevin were both raised as Catholics. Do you think the experience would have been different if you hadn’t had similar backgrounds?

MORISSETTE: Probably. I doubt I would have thought the movie was as funny as I did. I think that had a lot to do with the fact that I’ve been questioning my own Catholicism since as far back as I can remember.

WEITZMAN: In listening to your albums, it seems as though you’ve embarked on a pretty intense spiritual journey in the last several years. When did your doubts about Catholicism begin?

MORISSETTE: When I was 11 years old and I was on a road trip with my family. I turned to my dad and said, “Do you believe in Adam and Eve?” And he said he didn’t think so. I remember that felt like a slap in the face, because if my parents questioned Adam and Eve, then they potentially questioned everything within Catholicism. Eventually that idea led to my feeling liberated, but at that time it was very scary. From that moment onward, I questioned our faith entirely?

WEITZMAN: How did your parents feel about that?

MORISSETTE: They weren’t overly strict about my personal beliefs, but I still went to Catholic school and to church every Sunday until my late teens.

WEITZMAN: The negative reaction of the Catholic League to Dogma obviously brings up issues of censorship, which is something that you’ve experienced yourself.

MORISSETTE: My take on such violent reactions is that it’s exciting for people to define who they are in relation to what I write—whether it be by loving or hating it. It’s the same with Kevin’s movie. When someone has a very urgent response, I think it just means that it’s triggering something in them that they may not necessarily want to think or talk about—which I see as a positive thing.

WEITZMAN: So then calls for censorship don’t really offend you?

MORISSETTE: In a perfect world, there would be no censorship, because there would be no judgement. I find the hypocritical aspect disconcerting, to say the least. We can show people being murdered on television, but I’m not able to say “chickenshit” in public. At the same time, I understand that people are afraid. Because I think censorship is about fear. It’s just fear being projected onto art.

WEITZMAN: Then you think that the reaction of the Catholic League stems from fear?

MORISSETTE: Absolutely. In my life, anyway, anytime that I judge something to be rigidly right or wrong, it comes from fear.

WEITZMAN: The concept of a God in feminine form has proven to be pretty controversial.

MORISSETTE: I think the Bible is hugely patriarchal. There are so many sexist comments and homophobic comments and comments that are not in keeping with nurturing and loving the human spirit. But that’s found with so many religions.

WEITZMAN: What’s your image of God?

MORISSETTE: Female, male, inanimate, plant. I think God is everything. Human beings created the punitive, vengeful deity who considers us to be innate sinners.

WEITZMAN: The chorus in your song “Forgiven” goes, “What I learned I rejected but I believe again.” What specifically did you reject?

MORISSETTE: I rejected the God that was portrayed as masculine and judgmental and cruel at times. The concept of us bring not worthy to receive him is something I used to say every Sunday in church, and eventually I just couldn’t say it with any conviction.

WEITZMAN: What was it that you said, exactly?

MORISSETTE: When we were about to go to the front of the church to receive the host—which is in Catholic belief the body of Christ—we had to say, “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word, and I shall be healed.” That puts people in a position where they feel inferior to God and where they don’t feel like they’re responsible for their own actions. Whereas I believe we’ve been given free will, and we can take responsibility for our own lives and for creating our own environments—which I think at times can be a little much for people to deal with. Certainly it is for me.

WEITZMAN: What’s the biggest question that you currently have on a spiritual level?

MORISSETTE: I don’t really have any.

WEITZMAN: None?

MORISSETTE: No. that’s not to say I don’t feel any dissonance. But when I do it’s because I’m looking outside myself.

WEITZMAN: Tell me what you mean by “looking outside myself.”

MORISSETTE: Looking for approval or blaming others or feeling like a victim. Whenever I feel myself doing that I try to stop and see myself as someone who’s a creator in more ways than just what the word typically means.

WEITZMAN: Then do you see God not as a being that’s around us but, rather, inside us?

MORISSETTE: I think God is in us. I think we manifest God in every moment.

WEITZMAN: Does that include the manifestation of bad things?

MORISSETTE: I don’t believe in bad. I believe in relativity. The only way we can know what we call good is if there’s also something we call bad.

WEITZMAN: You spent some time at Mother Teresa’s hospital and orphanage in India after your Jagged Little Pill tour, so I imagine that you’ve certainly seen what other people would call tragedy. How do you look at that, if not as bad?

MORISSETTE: I see it as a consequence of our forgetting who we are. Forgetting that we’re able to create our environment, from our health to economy to war. Something can be done about everything we perceive as bad, if we so choose. If we are aware of the concept of compassion.

WEITZMAN: In Western culture, fame is often considered to have the power to elevate a person in the way spirituality might.

MORISSETTE: Oh, yeah. It’s an extremely false sense of power, however. Very fleeting, very illusory. I do feel blessed to be in the public eye so I can share what I believe. But I think it would be extremely disappointing if I were to count on it to provide happiness. I’ve come to realize that any time I do that, the fulfillment is short-lived at best.

WEITZMAN: Were you ever led to believe that fame would make your life complete?

MORISSETTE: Unquestionably.

WEITZMAN: By who? Parents, record executives, yourself?

MORISSETTE: Everyone. All of the above. Society, magazines, posters, music videos, investment bankers. A lot of times, in my past anyway, looking within wasn’t overly encouraged. Pretty much everybody proclaimed that fame would give me power and fortune.

WEITZMAN: When you decide to appear on the cover of Rolling Stone, or in a video on MTV, do you think in some way it might encourage another little girl to believe that answers can be found in stardom?

MORISSETTE: I don’t, only because I’m overly concerned about not living in a way that perpetuates that myth. And if I do buy into it in certain moments, people around me quickly call me on it. [laughs] Although, you know, I would never judge someone’s intrigue with the spoils of fame, because I went through that.

WEITZMAN: There’s a tendency to think of high-profile celebrities as deities of sorts. Since you’ve always been very careful not to buy into the concept of the rock goddess, isn’t it, for lack of a better word, pretty ironic that you’re playing God?

MORISSETTE: Yeah. [laughs] In one breath, I can say that we are God, but in another I have to say that we aren’t deities.

WEITZMAN: Do you ever find yourself in the position of having to compromise, or face off against people who have different values or motivations than you?

MORISSETTE: I don’t think I’ve ever compromised.

WEITZMAN: In your whole life?

MORISSETTE: With my career, I don’t think I ever really have. If I have taken part in anything perceived as the fame machine, it’s been my choice. My motivations certainly have been different from some people’s that I’ve worked with. But it’s okay to work equally passionately for two different reasons.

WEITZMAN: Have you hd to fight to remain uncynical?

MORISSETTE: For a long time, during Jagged Little Pill, when everything was so new and so overwhelming, I definitely went into self-protective mode.

WEITZMAN: When I watched you sing “You Oughta Know” at the taping of your MTV Unplugged session, it seemed like you still feel all the pain of that song’s original intent. Is it ever difficult to relate to a song you wrote years ago?

MORISSETTE: No. It’s not hard to feel afraid and insecure. I still fight an inner-critic voice, definitely. I hear it a lot.

WEITZMAN: Does it ever win?

MORISSETTE: Yeah. Absolutely.

WEITZMAN: For Unplugged, you covered the Police’s “King of Pain.” You’ve been labeled a queen of pain more than once. Is choosing a cover like that sort of like playing God?

MORISSETTE: [laughs] I guess I’d have to say there’s a little bit of a satire thing going on. Not agreeing with those kinds of labels doesn’t negate the fact that I have pain, or that I am at times [laughs] both angry and female. But being viewed one-dimensionally as those things is where the bigger picture gets missed.

WEITZMAN: One more spirituality question: Do you pray?

MORISSETTE: I guess you could call it praying. When I do it, I’m just talking to what some people might call our higher selves: God, myself, my intuition, my heart. Whatever that is, that’s where I go.

INTERVIEW

No comments:

Post a Comment