The Best Books of 2023

Ten authors whose original ideas challenged our preconceived notions of the world.

Each year, we experience a bounty of excellent new books being published, and if we’re lucky, we’re able to read a tenth of them by December. 2023 is no different. In a year when many un-consenting authors found their works being used to train artificial intelligence, it feels extra crucial to celebrate original thinking. From heavily reported nonfiction on topics that were hitherto obscured, to thrillers that shocked us after we thought we’d seen it all, to poetry collections that made us rethink our perspective on the world, there was much to enjoy. Here, some of the very best.

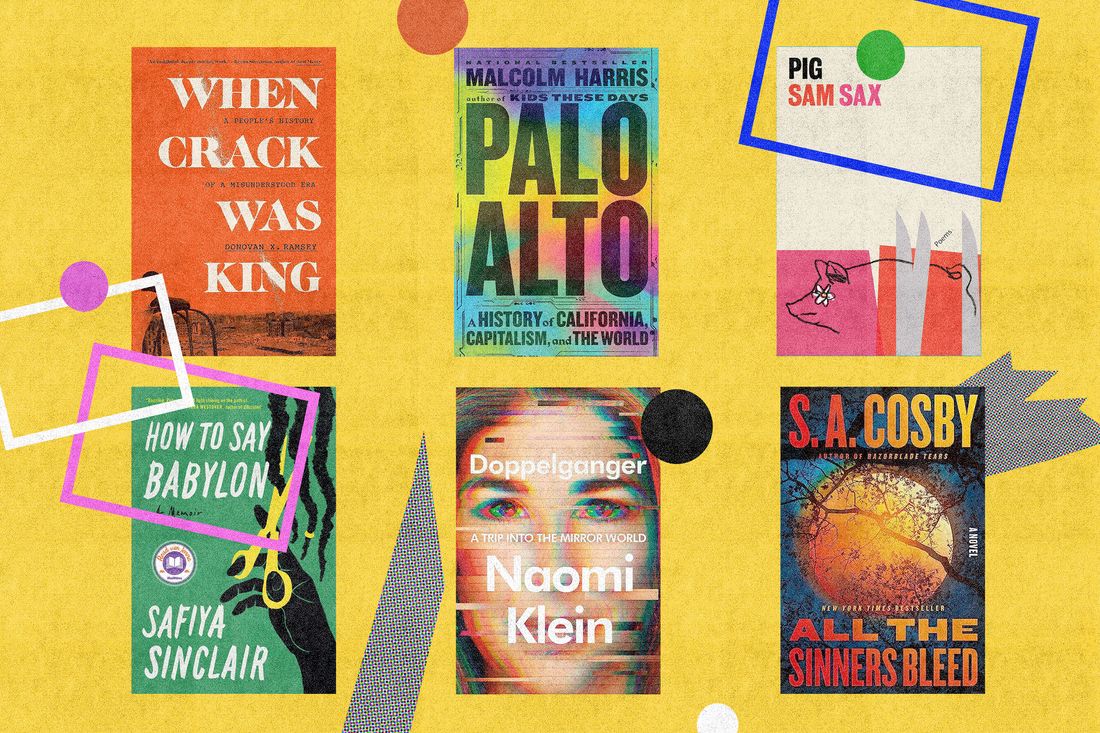

Raw Dog, by Jamie Loftus (Forge/Macmillan)

The public appetite for single-topic cultural histories in the vein of Mark Kurlansky’s Salt seems insatiable, so we are very lucky to finally have the definitive consideration of the hot dog. Comedian and podcaster (My Year in Mensa, Aack Cast, and more) Loftus takes us on a journey both silly and profound as she traverses the country on a quest to find the best franks and wieners, filling it all out with the ethnic and economic evolutions of the modest food (as well as its labor history). Packed with fun and some angst and a few digressions on gastrointestinal distress, Loftus’s journeys take her from the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile to Coney Island’s notorious hot-dog-eating contest and all the personalities and politics surrounding them. For extra laughs, listen to the audiobook, which the author narrates in her inimitable voice. Missing that would be as big a sin as putting ketchup on a dog in Chicago.

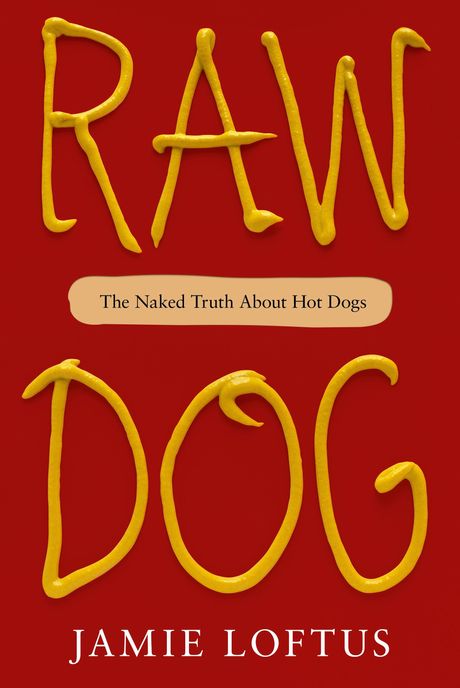

Pig, by Sam Sax (Scribner)

In a collection organized around an unlikely theme, Pig allows the poet to experiment with form and draw connections between seemingly unrelated phenomena. Sax is concerned with both the literal body of the pig as well as its connotations: as swine, as cops, as unkosher, as dirty, as pop-culture phenomena, as an oftentimes-queer sexual preference. A wholly original mix of comedy and tragedy, Pig contains visual diversity (the circular “Porchetta Di Testa, Or Rolled-Up Pig Face” is a standout) as well as rhyme schemes that hint at the poet’s dark sense of humor. From an ode to Miss Piggy as a queer icon to a poignant yet arch meditation on observing Yom Kippur (“Easy Fast Queers”), Pig ingeniously finds grace in the profane and beauty in the wretched.

8.

All the Sinners Bleed, by S.A. Cosby (Flatiron)

The best thriller of 2023 is a briskly paced, action-packed stunner underpinned by a slew of thorny philosophical and moral questions. For one, is it possible to change institutions, rotten to the core, from within? Titus Crown, a former FBI agent with an impeccably organized closet, thinks it just might be. In 2017, Titus takes a job as the first Black sheriff in his hometown of Charon County, Virginia, a place where monuments to Confederate heroes still stand. A teacher’s murder at the local high school sets off a chain of violence that sends Titus — and Charon County — into a frenzy. As the comfort of his routine falls away and Titus grasps for control, he uncovers the work of a serial killer whose unspeakable crimes have been peppered with religious iconography. Titus’s fevered search for the perpetrator and his reckoning with the conditions that enabled such evil to fester are utterly compelling, but his tender reconciliations with his brother and their ultrareligious father are the true heart of the story.

|

| Lorrie Moore by Triunfo Arciniegas |

7.

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, by Lorrie Moore (Knopf)

It’s a travesty that Moore has never won a major literary prize for her novels, and her most recent is a shining example of the style that makes her stand out among other fiction writers. You don’t read Moore for plot but rather for her characters, their emotions, and the off-kilter yet entirely apt thoughts that run through their heads. I Am Homeless begins in New York City in 2016, interweaving a historical epistolary narrative with a weird and wonderful ghost story.Suffering from the kind of grief that bends reality, Finn goes from visiting his brother in hospice to taking a road trip with Lily, his recently deceased ex-girlfriend, to deliver her to a Southern body farm. But don’t worry about the story line! A line from Zombie Lily pinpoints so much of the magic of Moore’s writing: “Jokes are flotation devices on the great sea of sorrowful life. They are the exit signs in a very dark room.”

6.

How to Say Babylon, by Safiya Sinclair (Simon & Schuster)

When a poet of Sinclair’s caliber (Cannibal, 2016) writes a memoir, it almost doesn’t matter what she writes about; she is certain to dazzle with her language. But Sinclair’s history makes for a rich subject matter, having grown up in Jamaica in a Rastafari family. Despite the obtuse American conception of the laid-back Rasta enforced by Bob Marley posters in college dorms, Sinclair’s subjects are both a historically persecuted minority and a fundamentalist sect with stifling constraints built around a patriarchal obsession with women’s purity. Sinclair’s father was the arbiter and enforcer of all Rastafari principles, implementing strict rules on how to dress and behave. Under such stifling influence, Sinclair, her siblings, and their mother, described as a “coven of overachievers,” turn to art and poetry and education of all sorts for sustenance. Year by year, we witness Sinclair’s growth and her awakening to the outside world as she discovers her true priorities and activates her own beautiful voice.

5.

Palo Alto, by Malcolm Harris (Little, Brown)

A sweeping biography of a place where efficiency and profitability dominated long before the tech industry as we know it ever existed, Palo Alto is an astute unraveling of how we got here. In an entirely engaging narrative voice, author Harris considers his hometown, where obsession with optimization illuminates capitalism run amok. Harris uses a wide lens to illuminate how seemingly disparate branches of history are actually connected, starting with the establishment of the suburban Northern California town on stolen land, reaching through 19th-century railroad robber barons and gold-rush fortune-seekers, all the way to 20th-century weapons manufacturing and current-day venture-capital-crazed start-ups. Throughout, Harris foregrounds the exploitation of labor in this wealthy town, the way squeezing productivity out of employees was a feature of Palo Alto’s culture that presaged Silicon Valley’s ill treatment of its lowest-rung workers.

4.

Biography of X, by Catherine Lacey (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

One of many excellent novels published in 2023 that blur the line between fact and fiction (Same Bed Different Dreams, by Ed Park; The Maniac, by Benjamín Labatut; Blackouts, by Justin Torres), Biography of X plays with the slippery borders between real-life historical figures and fictional characters. The artist X is a Kathy Acker–type maverick whose shape-shifting identity through the decades has created a mythos around herself and her work. When she dies, her widow attempts to write a book about her life, and the research leads to unexpected places and some pertinent questions: Can we ever really know someone? As a fan? As a spouse? Was X’s whole life’s work just an elaborate bit?

On top of X’s story, Biography of X is also an alt-history of America in which the Northern and Southern Territories of the country have reunified after splitting at the end of WWII. Lacey pulls off a virtuosic feat in footnotes and endnotes, embedding fictional events for real-life characters in the world of the book (one citation is a Renata Adler book of reporting from undercover in the Southern Territory published by FSG in 1978). Lacey nails the aphorisms of a downtown legend, the ones that come from real sources and fictional ones. Every detail is immaculate.

3.

When Crack Was King, by Donovan X. Ramsey (One World)

Ramsey’s debut work of reported nonfiction is both a deeply researched and deeply felt exploration of the 1980s crack epidemic told from many angles. Throughout the book, Ramsey alternates between chapters that detail what was happening legally and culturally in American society as a whole, juxtaposed with the personal stories of four people whose lives were profoundly changed by the rise of the drug. His extensive interviews with Lennie Woodley in South Central Los Angeles, Elgin Swift of Yonkers, Shawn McCray of Newark, and Kurt Schmoke of Baltimore provide a much-needed counterpoint to the sensationalist media coverage that aided in utterly dehumanizing the epidemic’s victims at the time. He also shows how, after politicians and police declared a war on drugs rather than helping those in need, the communities that were most vulnerable managed to save themselves.

2.

Enter Ghost, by Isabella Hammad (Grove)

It’s both a truism and wonderful cliché that art is essential in times of turmoil, that great art can help to make sense of the world even if it’s not nearly enough to save us. Hammad’s astonishing second novel captures this bittersweet contradiction in the story of Sonia Nasir, a Palestinian London actress, who returns to Israel to visit her sister and is enlisted to play Gertrude in an Arabic staging of Hamlet to be performed in the West Bank. In the shadow of IDF checkpoints and interrogations, the cast mounts a scrappy and spirited production infused with subtext, even as it accounts for a production in which Ophelia was portrayed as a suicide bomber. Flashbacks from Sonia’s childhood summers in Haifa underscore how it is never too late for a political awakening, especially under circumstances that are as devastating as any Shakespearean tragedy.

Doppelganger, by Naomi Klein (FSG)

No recent book has better captured the absurdities and perils of the current moment in politics and culture and digital life than Doppelganger. The premise might seem gimmicky: Progressive writer Klein explores how the other author with whom she’s constantly confused, Naomi Wolf, became red-pilled. But Other Naomi’s descent into right-wing madness is just a jumping-off point for Klein to explore a shadow world that exists concurrent to our own, where facts are malleable and disinformation is abundant, where conspiracy theories distort and exploit our very legitimate fears, and where fascism can arise as democracy’s evil twin.

This book is a must-read even before Klein gets to unforgettable observations about ethnic doppelgängers and her experience as a Jewish woman who once reported from Gaza. With humor and empathy and a sharp eye that can deconstruct systemic injustices with the same ease as Twitter drama, Klein uses copious film and literary references as she skewers everything from the wellness industry to AI.

No comments:

Post a Comment