My heroes: CS Lewis by Laura Miller and Aldous Huxley by Nicholas Murray

Laura Miller cherishes Lewis's literary criticism, while Nicholas Murray admires Huxley's exemplary open mind. Lewis and Huxley both died 50 years ago, on 22 November 1963

History may be written by the victors, but an author's reputation is made by the keepers of the flame. In the case of CS Lewis, who died on 22 November 1963, the keepers are Christians, many of them American evangelicals, and, with the exception of his children's fiction, a glance at the shelf of his books kept in print by their enthusiasm might lead you to conclude he was primarily a popular theologian. But Lewis had a day job, as a tutor and fellow in English literature at Oxford and Cambridge, and if, like me, you far more interested in his literary criticism than his apologetics, you often have to scrounge up shabby used copies of those titles online.

Almost obscured by the dominant picture of Lewis as a sort of modern-day Protestant saint is the Lewis who wrote those works, the Lewis I admire. He was one of the world's great readers. The critic William Empson once described him as "the best read man of his generation, one who read everything and remembered everything he read", which included obscure allegorical Latin poets of the late classical period, who are nowadays justifiably forgotten. Yet there's never a sense in Lewis's literary scholarship of the accumulation of expertise for its own sake. He read omnivorously and for pleasure, first and foremost. If his opinions and observations on the world sometimes reflected the narrow, old-fashioned views of his middle class Anglo-Irish background, he was always willing to extend and expand himself to meet an author halfway. His writing on the joys of reading verges, at times, on the erotic.

Apart from the Narnia books, the work of Lewis's I most cherish, "An Experiment in Criticism", makes the almost postmodern – and at the very least radically humble – proposition that we might best judge the literary merit of a book not by how it is written, but by how it is read. If "we found even one reader to whom the cheap little book with its double columns and the lurid daub on its cover had been a lifelong delight, who had read and reread it, who would notice, and object, if a single word were changed, then, however little we could see in it ourselves and however it was despised by our friends and colleagues, we should not dare to put it beyond the pale". That is a faith I am happy to share.

Laura Miller's The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia is published by Little, Brown.

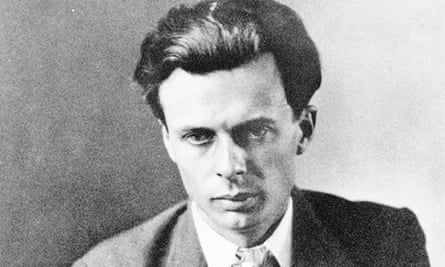

Aldous Huxley, the tall, short-sighted, cerebral English writer who ended his life 50 years ago in Hollywood as a modern guru, might seem an unlikely hero. But in writing his life I grew to admire his resilience – overcoming temporary blindness, childhood traumas and, later, permanent poor sight – and the quiet courage of his particular brand of liberal individualism.

Collared by a journalist on his arrival in the US in the middle of the 1926 general strike, he described his politics as "Fabian and mildly labourite", but he was never a political partisan, and his free-ranging intellect was incapable of being pressed into a sectarian mould. Yes, he was an old Etonian – posh, successful very early, always the mild and courteous, silver-voiced English gentleman that one of his Hollywood neighbours watched in fascination putting out a bag of garbage with the delicate grace of a court chamberlain – but he had the courage of an exemplary open mind. The FBI kept a fat file on him but failed utterly to find anything damning (as his biographer I was sorely disappointed when it slid out of the jiffy bag). He was nevertheless refused US citizenship – a rejection that wounded him – and his British critics, predictably indicting his residence in the US during the war, are still to be found in conservative newspapers and academic conferences where they try to pin sinister labels on him.

He has survived his detractors and remains an eloquent critical voice, warning against our tendency to "love our slavery" – Brave New World's dystopian idea of manipulation and conformity and our tendency to submit to soft power, so clearly vindicated by the extraordinary complacency with which the public seems to have greeted the Snowden revelations of illegitimate surveillance. A free democrat to the core of his being, at war through words with "the great impersonal forces now menacing freedom", he shows that heroism can exist away from the noisy battlefield.

No comments:

Post a Comment