Who “wrote” Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller

Ajam Media Collective

This article was written by a guest contributor and solely reflects the views of the author.

following is a guest post by Arafat A. Razzaque, a PhD candidate in History & Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. He specializes in medieval Islamic social and cultural history, and has a secondary interest in the Thousand and One Nights, stories from which he first read in Bengali translation.

This article is the second of a two-part series about Aladdin. Part one, entitled “Who was the “real” Aladdin? From Chinese to Arab in 300 Years” is available here.

***

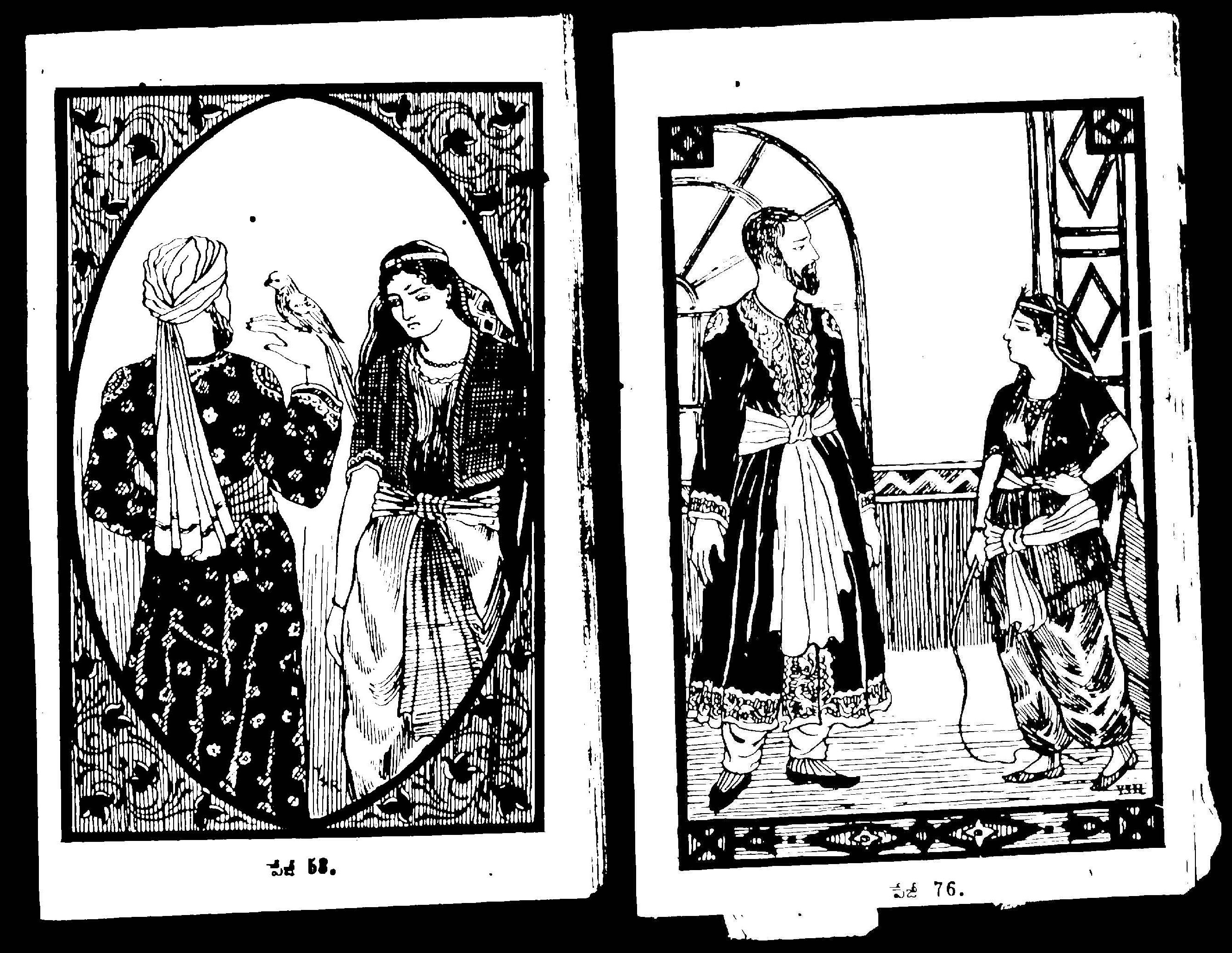

Long before podcasts, the twentieth century’s first media revolution gave birth to what is called radio drama. In the 1950s, Egyptian Radio began broadcasting arguably the Middle East’s greatest modern adaptation of the 1001 Nights. It was produced by a pioneer of Arabic children’s programming famously known as Baba Sharo, who was a student of the towering Taha Hussein and later became the station’s chairman. Written by the poet Tahir Abu Fasha (who also wrote songs for Umm Kulthum), the series lasted 26 years on the airwaves, with 820 episodes total. As a child, the Lebanese novelist Hanan al-Shaykh would sit “glued to the radio” waiting to hear the captivating Zouzou Nabil, who voiced Shahrazad.

Today, listening to the program’s archives (officially uploaded to Youtube last year) is a striking reminder of the many classic yet obscure tales that make up the vast corpus of 1001 Nights. But for the past two centuries in the West and now throughout the world, only the stories of Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sindbad have been the most iconic and well known. This is often considered a great irony since none of these three were originally part of the Arabic Alf layla until the first French edition.

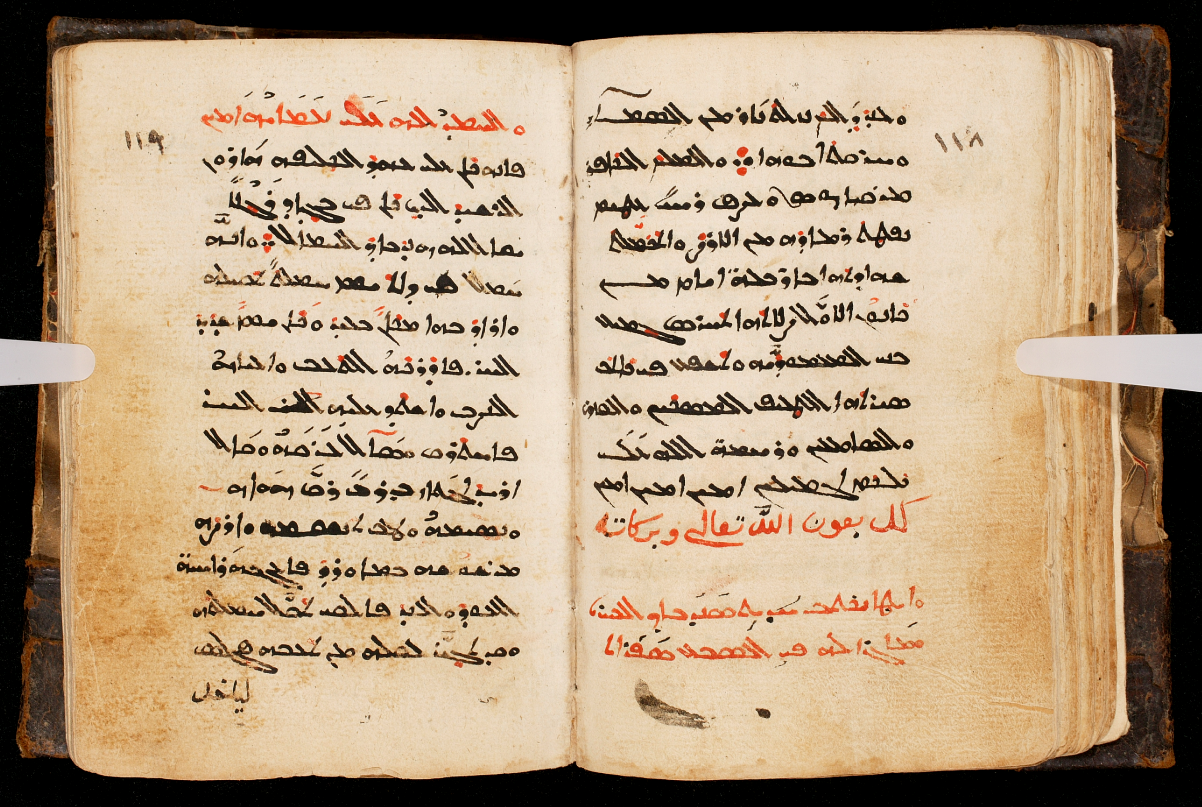

Of course, from its ancient roots to its codification in medieval Arabic, the 1001 Nights was reinvented many times over the course of a millennium. Its recent history was dominated by Western fascination, as it became a driving force of Orientalism and inspired colonial administrators to spend their free time studying and translating the text. Generations of readers have obsessed with finding the most accurate version of the tales, and were even duped by manuscripts forged by clever Arab scribes, including some diasporic Syrian Christians in Paris.

One figure in particular played a crucial role but has been largely overlooked: a little-known man from Aleppo named Ḥannā Diyāb who gave the modern world some of its most influential and popular stories ever. The equally astonishing recent discovery of Diyab’s autobiography at the Vatican Library finally allows us to learn more about someone who remained a mystery for so long. It shows us that to solely attribute Aladdin to a Frenchman, whether as credit or critique, is quite mistaken.

The Making of a Tradition

The 1001 Nights has a pretty remarkable genealogy. Our oldest documentation of it is an Arabic papyrus from Egypt, reused as scrap with inscriptions dated 879 CE. There was an earlier Persian book called Hazār afsāna (A Thousand Stories) that did not survive. But key elements of the frame story of Shahriyar and Shahrazad were already common in Pali and Sanskrit texts from ancient India, while another Arabic book called One Hundred and One Nights has an alternate version also found in a third-century Chinese Buddhist text of the Tripiṭaka.

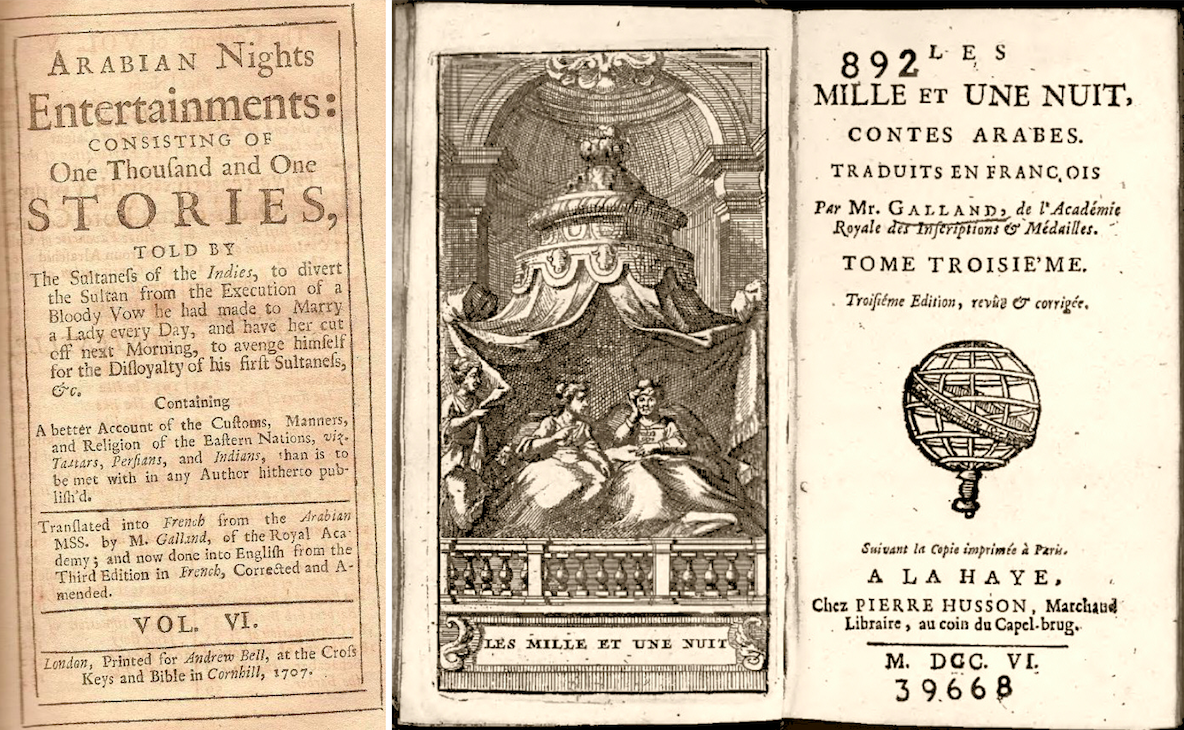

The event that sparked the Nights into a modern European phenomenon was its translation by Antoine Galland from a fifteenth-century Arabic manuscript that still remains our principal source. First published in 1704, Galland’s Les Mille et une nuit: Contes Arabes (“1001 Nights: Arabian tales”) was an instant bestseller, mainly because it coincided with the rise of French fairy tales.

Cheap pirated copies in English of so-called Arabian Nights’ Entertainments appeared almost immediately on London’s Grub Street. This anonymous translation-of-a-translation thus modified Galland’s subtitle, and the phrase “Arabian Nights” became a fixture ever since. Given that the original story has Shahriyar as “sultan des Indes” (in Galland’s phrasing), the early English title also highlighted Shahrazad’s role as narrator by adding: “Stories told by the Sultaness of the Indies.”

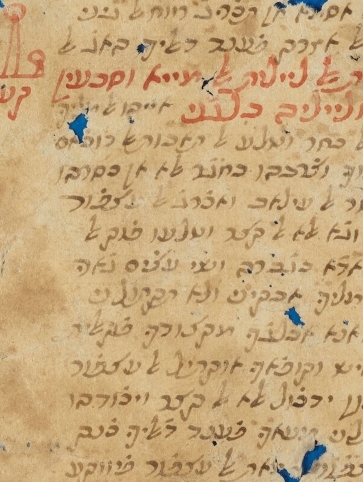

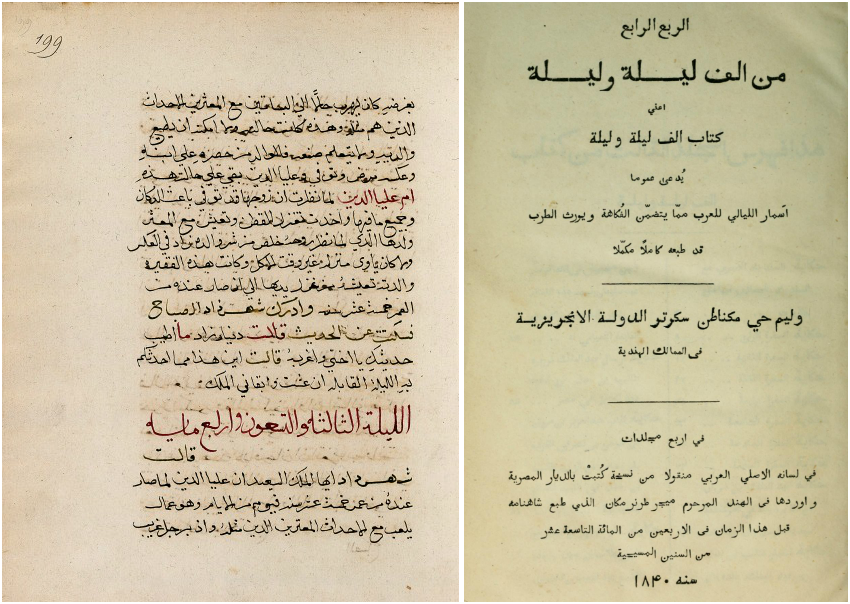

In Arabic, Alf layla was first printed in India. Known as the “Calcutta I” edition of 1814–18, it was prepared by Shaykh Aḥmad al-Shīrwānī, a teacher of Arabic at the Fort William College in Bengal, where East India Company officials were trained in South Asian languages, especially Persian. Subsequent Arabic editions were published in Breslau, in today’s Poland (by Habicht, 1824–43), in Bulaq, Cairo (1835) and again in India (“Calcutta II,” 1839-42). By the late-nineteenth century, the book was appearing everywhere—a fascinating example being the Judaeo-Arabic edition of 1888 printed in Bombay by Aharon Yaacov Shmuel Divekar, a native Jewish-Indian (“Bene Israel”) who also published prayer books for the city’s Baghdadi Jewish community.

Amazingly, none of these Arabic versions included the story of Aladdin, even though the books were tampered to begin with (Habicht faked his sources and his Breslau edition was partly copied into Calcutta II). For European Orientalists endlessly searching for a complete text, the idea that Galland “interpolated” a dozen stories was basically a literary scandal. With no known textual origins, these are now called “orphan tales.”

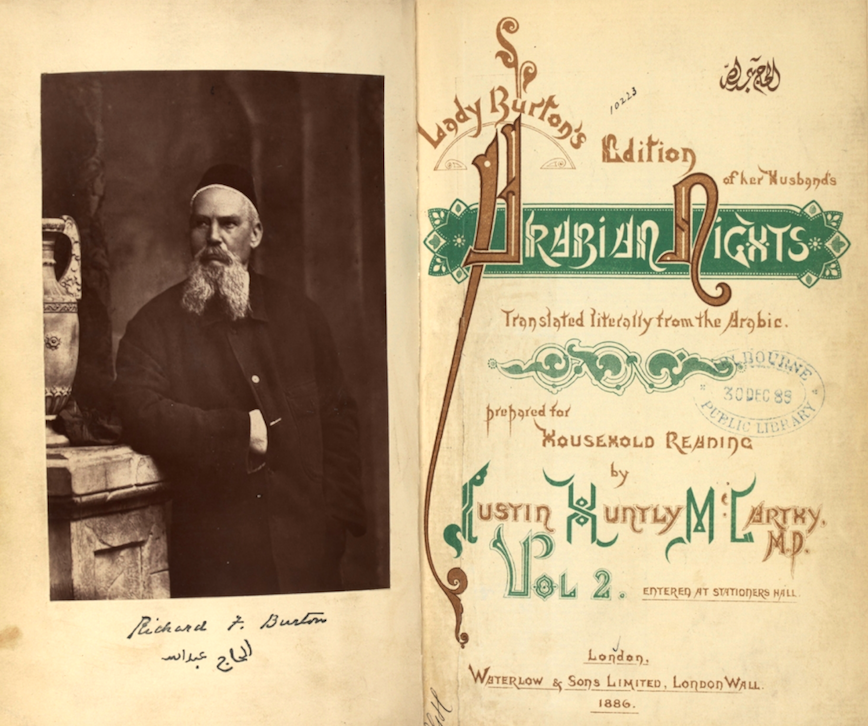

Scholars would joke that Galland found these stories “in the public libraries of Paris.” But Richard Burton still had faith in Aladdin, writing in 1886: “As regards Aladdin, the most popular tale of the whole work, I am convinced that it is genuine.” He points to some internal evidence: the setting is China, and the story says at one point “they drink a certain warm liquor” there. That is tea, Burton observes, so the text is consistently Eastern!

Burton’s reasoning reflects a frequent concern that readers had with Frenchisms in Galland’s Nights, which made some people doubt its Oriental authenticity. The incredible irony, however, is that Burton’s own translation was not directly from Arabic, but instead a plagiarized reworking of other English translations that he deliberately foreignized with his famously archaic language. Even more eccentric, he wrote that for the orphan tales: “My first thought…was to render the French text into Arabic, and then to retranslate it into English.” But a friend sent him from Bombay a “quaint” Urdu translation of Galland, which seemed “sufficiently orientalised and divested of their inordinate Gallicism.”

Recuperating Hanna Diyab

After nearly a century of speculation, in 1887 the Prussian scholar Hermann Zotenberg who worked as a manuscript curator at the French national library, came across Galland’s archived diaries. There it was revealed that Galland had an oral source, “the Maronite Hanna of Aleppo.”

Meeting Hanna Diyab in 1709 through a colleague in Paris was great luck for Galland, since he ran out of stories to translate from available manuscripts. In fact, much to his dismay, that year his publisher would release volume 8 of the Nights under his name but inserting two other stories from a rival French Orientalist.

Galland wrote in his journal that he received “the Story of the Lamp” from Hanna Diyab on May 5, 1709. Every few days for the next month or so, Diyab told him fifteen more tales. Ten of these, including Ali Baba, were later published as the last four volumes of Galland’s Nights (1712–17).

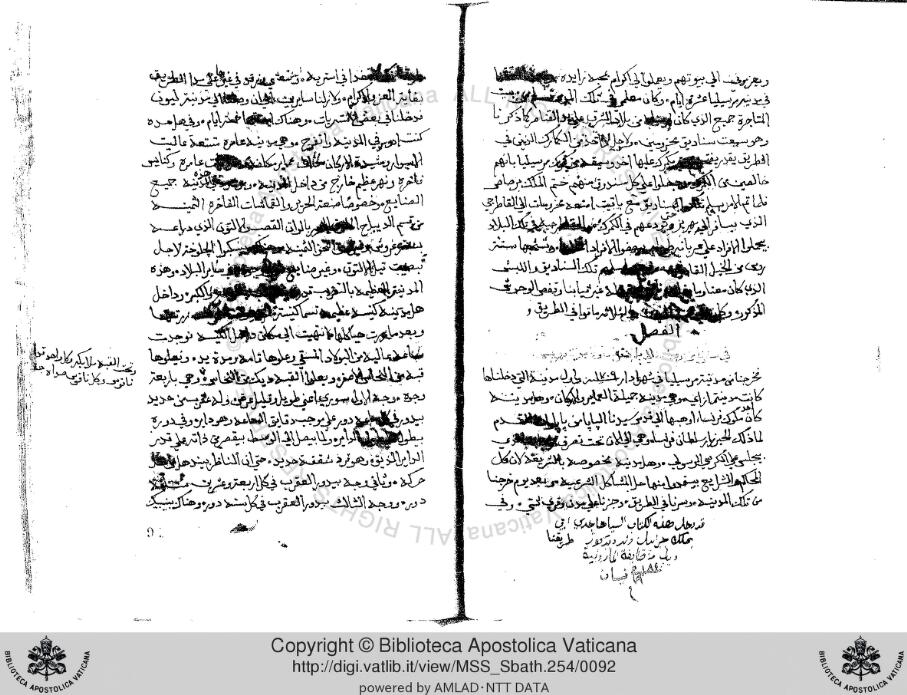

Despite finding out about Diyab, Zotenberg announced with excitement that he did identify two manuscripts for Aladdin, leading to the first published Arabic version of the story in 1888. Of the two manuscripts, one was from 1787 in the hand of Dom Denis Chavis (Dionysius Shāwīsh), a Syrian priest living in Paris. The other, from 1805-8, was by Michel (Mikhāʾīl) Ṣabbāgh, a Melkite Catholic native of Acre. Both were learned men employed at the royal library in Paris. But as we now know, both manuscripts were elaborate hoaxes claiming to “complete” the Nights based on alleged but non-existent sources. For the orphan tales, they simply “back translated” Galland’s French into Arabic!

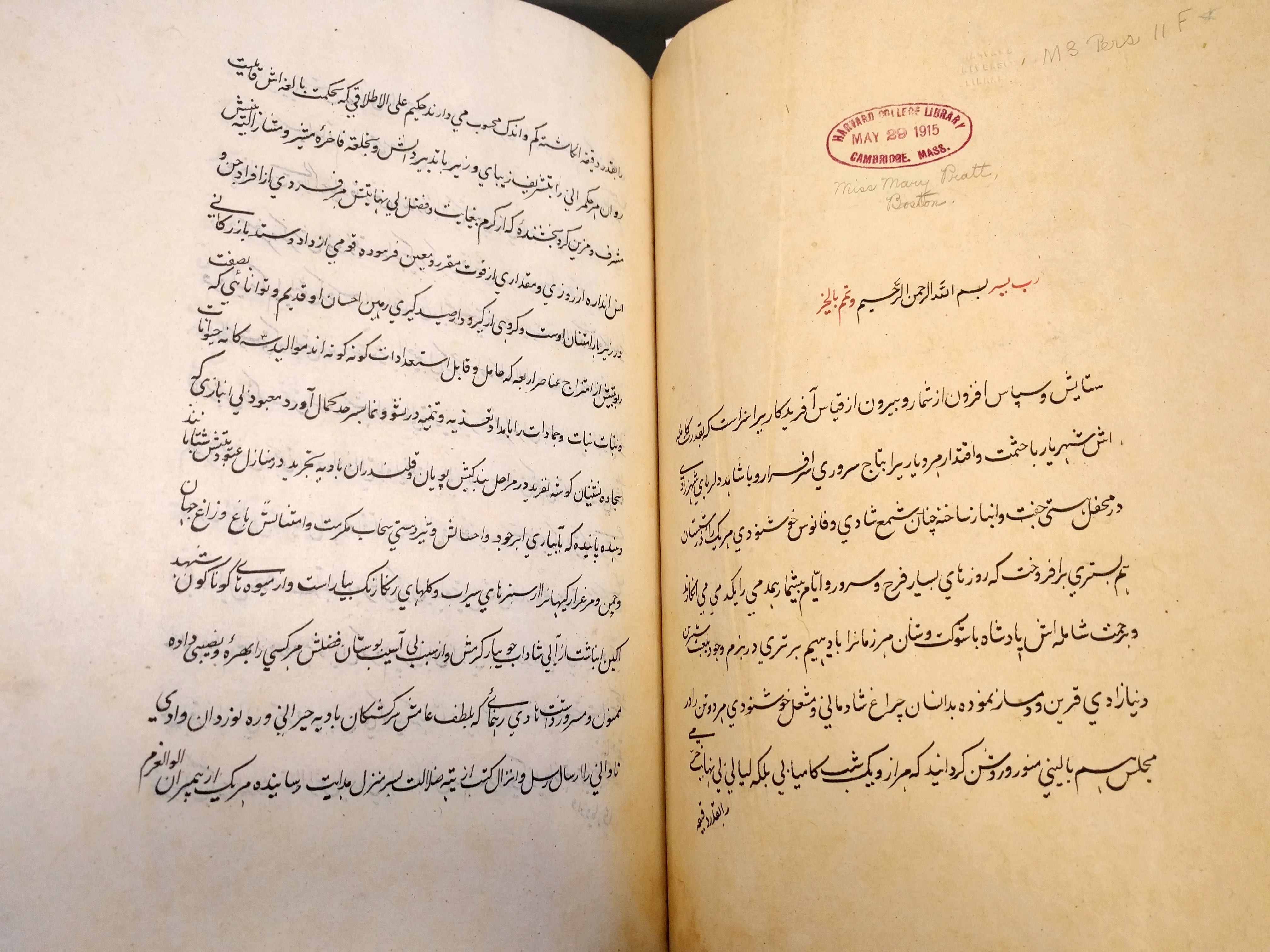

So it all keeps coming back to Galland’s oral informant. In 1993, a previously unknown autobiography/travelogue by Hanna Diyab was discovered at the Vatican Library. It has now been published in French as of 2015, and though of much broader historical interest, it also offers tantalizing glimpses into how Aladdin and Ali Baba came to be imagined.

From Aleppo to Paris

Anṭūn Yūsuf Ḥannā Diyāb was born in Aleppo to a Maronite Christian family. Having lost his father as a teenager, Diyab briefly entered a local monastery before turning his mind to other pursuits. In 1707, he joined a French expedition led by Paul Lucas, collector of antiquities for Louis XIV. As a servant and interpreter (dragoman), Diyab accompanied Lucas throughout his Mediterranean travels and was even presented to the “Sultan of France” at Versaille. Unable to secure a job in Paris that he was hoping for, in 1710 he returned to Aleppo, where he got married in 1717 and settled down as a textile merchant at the souq.

Diyab was around 75 years old by the time he wrote his autobiography in 1763. It recounts memories of real-life wonders and adventures, of bandits and betrayal, and of his occasionally suspicious master, the tomb raiding Paul Lucas. Soon after heading out from Aleppo, Lucas wanted to explore some church ruins in a Syrian village near Idlib. Always looking for archaeological treasures, he made a local shepherd go into a vault beneath a rock, from which the boy came out with an ancient ring and a lamp. Could this be a seed of what became the Aladdin story?

It remains difficult to say, as Paulo Horta argues in a fabulous new book, whether Diyab’s personal experiences informed the tales he told Galland, or if the tales influenced how he remembered his youthful adventures from over fifty years ago. Regardless, the autobiography reveals a person who clearly knew how to spin a story.

Yet Hanna Diyab had no idea of the international sensation his tales would create. He does not even recall Galland by name, and refers to him simply as “an old man.” Galland was 63 then (and died six years later in 1715), while Diyab was still in his early 20s. He writes in his memoirs:

There was an old man who often visited us. He was in charge of the library of Arabic books. He read Arabic well and translated books from it into French. At that time he had translated the book of Ḥikāyat Alf layla wa layla [Tales of 1001 Nights]. This man asked for my help on some issues he did not understand, so I explained them to him. There were some nights missing from the book, so I told him stories that I knew. Then he completed the book with these stories, and he was very pleased with me. (MS Sbath 254, f. 128a)

Like many Ottoman cities at the time, Aleppo was known for its coffeehouses and countless professional storytellers, so we have good reason to believe Hanna Diyab grew up learning many such stories.

Does this mean Diyab was transmitting Middle Eastern folklore? Here things get complicated. Scholars analyzing the orphan tales have noticed how they are characteristically more like European fairytales than the core of 1001 Nights, but it is not clear what came from whom. Does Aladdin’s palace seem so Baroque because of Galland’s editing, or because Diyab’s memoir describes with very similar wonder “the Sultan’s palace” in Versailles? More surprisingly, while it was usually assumed that Diyab narrated his stories in Arabic which Galland then translated, according to evidence uncovered by Ruth Bottigheimer, Galland’s notetaking suggests that Diyab dictated them directly in (accented) French. Diyab also knew Provençal, Italian, and Turkish.

In other words, although Galland treated Hanna Diyab as a native informant, his stories do not necessarily reflect a pristine Arab tradition. Growing up in Syria, Diyab may well have heard and/or read European tales. This should be little surprise given the ebb and flow of cross-cultural currents across the medieval Mediterranean. How else to explain that the Italian writings of Sercambi (d. 1424) and Ariosto (d. 1533) seem to include a parallel to the tale of Shahriyar, long before Galland’s translation?

Once again, both literature and folklore can unravel the myths of cultural purity we tend to hold so dear. A major classic of the Danish Golden Age happens to be an adaptation of Aladdin by Adam Oehlenschläger (1805), set in Isfahan rather than China because Persia was imagined to be the modern, cosmopolitan France of the East. Similar to many examples in European oral tradition, an indigenous Hungarian folktale recorded in 1874, the “Tale of a Gipsy Boy” turns out to be also derived from Aladdin.

Syrian Migrants of Another Time

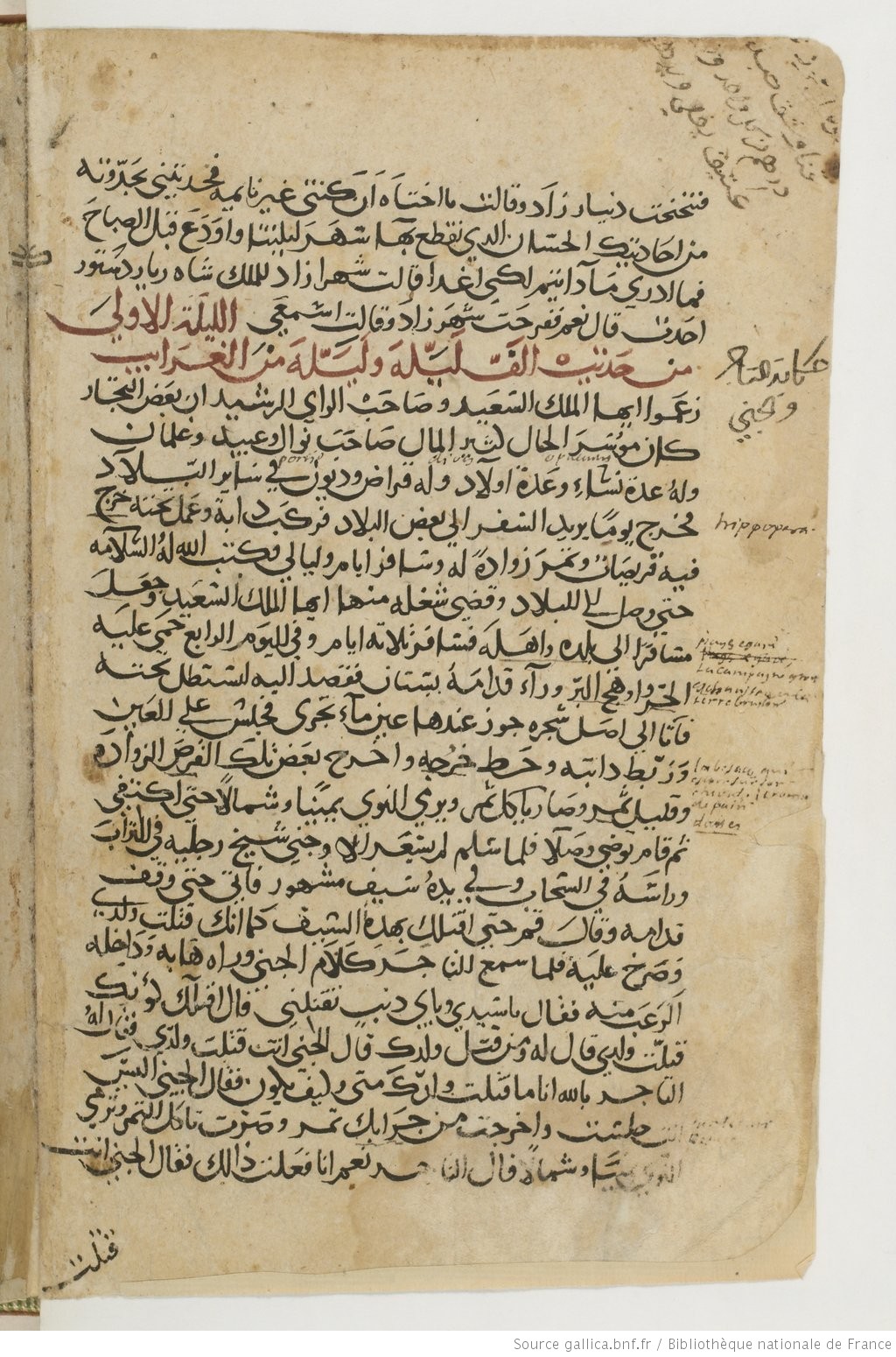

Although he mostly lived an ordinary life in Aleppo, Hanna Diyab belonged to an extraordinary Mediterranean diaspora that left footprints throughout the Levant, North Africa, and Europe. Like Chavis and Sabbagh a century later, Diyab was connected to a longstanding community of Syrian Christians residing in Rome and Paris since at least the sixteenth century. In fact, it was thanks to yet another friend from Aleppo that Galland first acquired his fateful copy of the 1001 Nights—a storied manuscript that, before ending up in France, had been passed down by dozens of readers both Muslim and Christian in the cities of Hama, Aleppo and Tripoli (Lebanon), many of whom inscribed their names in little marginal notations, with dates between 1505 to 1680 CE.

It is a shameful legacy of authorship that Galland never once bothered to name Hanna Diyab in his publications. In our haste to dismiss Aladdin as an Orientalist construct, we risk further perpetuating this erasure of someone who has been described as “probably the greatest modern storyteller known by name” (Marzolph 2012). No doubt, it is important to see “the Arabian Nights as an Orientalist text,” as in Rana Kabbani’s classic critique, and to interrogate the ways in which the 1001 Nights has long been used to uphold absurd stereotypes, not least by Disney. Likewise, as even its Arabic printing history suggests, we must remember how the text’s modern production was often tied up in the power dynamics of European colonialism.

But these necessary critiques should not be at the cost of negating the agency and creative imagination of “Orientals” themselves—not only Hanna Diyab, and the many forgotten native “assistants” to European scholars, but perhaps even, yes, the subversive forgers Chavis and Sabbagh!

References/Further Reading

The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Eds. Marzolph, Ulrich, Richard van Leeuwen, and Hassan Wassouf. 2 vols. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “East Meets West: Hannā Diyāb and the Thousand and One Nights.” Marvels & Tales 28.2 (2014), 302-24.

Dyâb, Hanna. D’Alep à Paris: Les pérégrinations d’un jeune syrien au temps de Louis XIV. Translated by Paule Fahmé-Thiéry, Bernard Heyberger and Jérôme Lentin. Arles: Actes Sud, 2015. (See also: Review in Al-Ahram by David Tresilian)

Horta, Paulo Lemos. Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Kallas, Elie. “Aventures de Hanna Diyab avec Paul Lucas et Antoine Galland (1707-1710).” Romano-Arabica XV (2015), 255-267.

Mahdi, Muhsin. The Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.

Marzolph, Ulrich.”Les contes de Hanna.” In: Les mille et une nuits. Eds. É. Bouffard and A.-A. Joyard. Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, 2012.

Oxfeldt, Elisabeth. Nordic Orientalism: Paris and the Cosmopolitan Imagination 1800-1900. Chicago: 2005

Rastegar, Kamran. “The Changing Value of Alf Laylah wa laylah for Nineteenth-Century Arabic, Persian and English Readerships.” Journal of Arabic Literature 36:3 (2005), 269-287.

Razzaque, Arafat A. “Genie in a Bookshop: Print Culture, Authorship and ‘The Affair of the Eighth Volume’ at the Historical Origins of Galland’s Nuits.” In: The Thousand and One Nights: Sources and Transformations in Literature, Art, and Science. Eds. Ibrahim Akel and William Granara. (Forthcoming)

No comments:

Post a Comment